Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

Essay 2 Sample Responses

Classics / WAGS 23: Second Essay Responses Grading: I replaced names with a two-letter code (A or B followed by another letter) so that I could read the essays anonymously. I grouped essays by levels of success and cross-read those groups to check that the rankings were consistent. Comments on the assignment: Writers found all manner of things to focus on: Night, crying, hospitality, the return of princes from the dead (Hector, Odysseus), and the exchange of bodies (Hector, Penelope). Here are four interesting and quite different responses: Essay #1: Substitution I Am That I Am: The Nature of Identity in the Iliad and the Odyssey The last book of the Iliad, and the penultimate book of the Odyssey, both deal with the issue of substitution; specifically, of accepting a substitute for a lost loved one. Priam and Achilles become substitutes for each others' absent father and dead son. In contrast, Odysseus's journey is fraught with instances of him refusing to take a substitute for Penelope, and in the end Penelope makes the ultimate verification that Odysseus is not one of the many substitutes that she has been offered over the years. In their contrasting depictions of substitution, the endings of the Iliad and the Odyssey offer insights into each epic's depiction of identity in general. Questions of identity are in the foreground throughout much of the Iliad; one need only try to unravel the symbolism and consequences of Patroclus’ donning Achilles' armor to see how this is so. In the interaction between Achilles and Priam, however, they are particularly poignant. -

Love's Labour's Lost

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS CAST Wednesday, November 4, 2009, 8pm Love’s Labour’s Lost Thursday, November 5, 2009, 7pm Friday, November 6, 2009, 8pm Saturday, November 7, 2009, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, November 8, 2009, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Shakespeare’s Globe in Love’s Labour’s Lost John Haynes CAST by William Shakespeare Ferdinand, King of Navarre Philip Cumbus Berowne Trystan Gravelle Artistic Director for Shakespeare‘s Globe Dominic Dromgoole Longaville William Mannering Dumaine Jack Farthing Director Set and Costume Designer Composer The Princess of France Michelle Terry Dominic Dromgoole Jonathan Fensom Claire van Kampen Rosaline Thomasin Rand Choreographer Fight Director Lighting Designer Maria Jade Anouka Siân Williams Renny Krupinski Paul Russell Katherine Siân Robins-Grace Text Work Movement Work Voice Work Boyet, a French lord in attendance on the Princess Tom Stuart Giles Block Glynn MacDonald Jan Haydn Rowles Don Adriano de Armado, a braggart from Spain Paul Ready Moth, his page Seroca Davis Holofernes, a schoolmaster Christopher Godwin Globe Production Manager U.S. Production Manager Paul Russell Bartolo Cannizzaro Sir Nathaniel, a curate Patrick Godfrey Dull, a constable Andrew Vincent U.S. Press Relations General Management Richard Komberg and Associates Paul Rambacher, PMR Productions Costard, a rustic Fergal McElherron Jaquenetta, a dairy maid Rhiannon Oliver Executive Producer, North America Executive Producer for Shakespeare’s Globe Eleanor Oldham and John Luckacovic, Conrad Lynch Other parts Members of the Company 2Luck Concepts Musical Director, recorder, shawms, dulcian, ocarina, hurdy-gurdy Nicholas Perry There will be one 20-minute intermission. Recorders, sackbut, shawms, tenor Claire McIntyre Viol, percussion David Hatcher Cal Performances’ 2009–2010 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. -

Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition

The MGB Challenge Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition Peter Bell, Jonathan Kilgour, Steve Renals, Mirjam Wester University of Edinburgh Mark Gales, Pierre Lanchantin, Xunying Liu, Phil Woodland University of Cambridge Thomas Hain, Oscar Saz University of Sheffield Andrew McParland BBC R&D mgb-challenge.org Overview Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Controlled evaluation of speech recognition, speaker diarization, and alignment Using a broad, multi-genre dataset of BBC TV output Subtitles & light supervision • Training data transcribed by subtitles (closed captions) – can differ from verbatim transcripts • edits to enhance clarity • paraphrasing • deletions where the speech is too fast • There may be • words in the subtitles that were not spoken • words missing in the subtitles that were spoken • Additional metadata includes speaker change information, timestamps, genre tags, … MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs • Acoustic model training 1600h broadcast audio across 4 BBC channels (1 April – 20 May 2008), with as-broadcast subtitles – ~33% WER (26% deletions) • Language model -

Resuscitation Resuscitation on Television

Resuscitation 80 (2009) 1275–1279 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Resuscitation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resuscitation Simulation and education Resuscitation on television: Realistic or ridiculous? A quantitative observational analysis of the portrayal of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in television medical dramaଝ Dylan Harris a,∗, Hannah Willoughby b a Department of Palliative Medicine, Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend CF31 1RQ, United Kingdom b University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Introduction: Patients’ preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) relate to their perception Received 21 May 2009 about the likelihood of success of the procedure. There is evidence that the lay public largely base their Received in revised form 4 July 2009 perceptions about CPR on their experience of the portrayal of CPR in the media. The medical profession Accepted 9 July 2009 has generally been critical of the portrayal of CPR on medical drama programmes although there is no recent evidence to support such views. Objective: To compare the patient characteristics, cause and success rates of cardiopulmonary resuscita- Keywords: tion (CPR) on medical television drama with published resuscitation statistics. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation Television Design: Observational study. Media Method: 88 episodes of television medical drama were reviewed (26 episodes of Casualty, Casualty, 25 episodes of Holby City, 23 episodes of Grey’s Anatomy and 14 episodes of ER) screened between July 2008 and April 2009. The patient’s age and sex, medical history, presumed cause of arrest, use of CPR and immediate and long term survival rate were recorded. Main outcome measures: Immediate survival and survival to discharge following CPR. -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

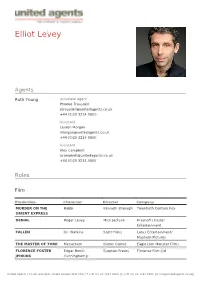

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

Casualty-S31-Ep44-One.Pdf

I have tried to show when we are in another LOCATION by using BOLD CAPITALS. I have used DUAL DIALOGUE as people talk over each other on a SINGLE SHOT. From the beginning - for the next hour - everything about ONE is to do with the inexorability of things in life and A+E. Time cannot be reversed, events cannot be interrupted. Like life. FIRST FLOOR OF SMALL HOUSE... Absolute stillness. At first we can’t work out what we are looking at. Just the green numbers of a digital alarm clock - 14.21. A horizontal slither of light, smudging with smoke. Somewhere close a baby gurgles and then coughs. Things are starting to get clearer. Then we hear JEZ shouting and coughing. JEZ(O.O.V) Hello? You in here... Hello? * You in here? * Hello! * She’s here! She’s ... * I got you. It’s OK. * Anyone there? Anyone... * I got her. I got her! * IAIN Was anyone else in there? You listening to me? Anyone else in there? JEZ * No! I shouted. Looked everywhere. No. SUN-MI * Leave me alone. I am OK. I want my * daughter. IAIN * Do you speak English? What’s your name? Miss? SUN-MI (in KOREAN) I want my daughter. JEZ What’s she saying? IAIN I don’t know. Let’s get her on O2 and check her Obs, yes, Jez? Episode 45 - SHOOTING SCRIPT 'One' 1. Casualty 31 Episode 45 - JEZ She was unresponsive when I got to her. Sorry, Iain. * IAIN * Late to the party again, boys. * Superman himself here... ... saw her at the window. -

![Seven Against Thebes [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8404/seven-against-thebes-pdf-1828404.webp)

Seven Against Thebes [PDF]

AESCHYLUS SEVEN AGAINST THEBES Translated by Ian Johnston Vancouver Island University, Nanaimo, BC, Canada 2012 [Reformatted 2019] This document may be downloaded for personal use. Teachers may distribute it to their students, in whole or in part, in electronic or printed form, without permission and without charge. Performing artists may use the text for public performances and may edit or adapt it to suit their purposes. However, all commercial publication of any part of this translation is prohibited without the permission of the translator. For information please contact Ian Johnston. TRANSLATOR’S NOTE In the following text, the numbers without brackets refer to the English text, and those in square brackets refer to the Greek text. Indented partial lines in the English text are included with the line above in the reckoning. Stage directions and endnotes have been provided by the translator. In this translation, possessives of names ending in -s are usually indicated in the common way (that is, by adding -’s (e.g. Zeus and Zeus’s). This convention adds a syllable to the spoken word (the sound -iz). Sometimes, for metrical reasons, this English text indicates such possession in an alternate manner, with a simple apostrophe. This form of the possessive does not add an extra syllable to the spoken name (e.g., Hermes and Hermes’ are both two-syllable words). BACKGROUND NOTE Aeschylus (c.525 BC to c.456 BC) was one of the three great Greek tragic dramatists whose works have survived. Of his many plays, seven still remain. Aeschylus may have fought against the Persians at Marathon (490 BC), and he did so again at Salamis (480 BC). -

Ancient Greek Culture, with Its Myths, Philosophical Schools, Wars, Means of Warfare, Had Always a Big Appeal Factor on Me

Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för Humaniora Kandidatuppsats 15 hp | Litteraturvetenskap | Höstterminen 2009 This war will never be forgotten – a study of intertextual relations between Homer’s Iliad and Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy Av: Ieva Kisieliute Handledare: Ola Holmgren Table of contents Introduction 3 Theory and method 4 Previous research and selection of material 6 Men behind the Iliad and Troy 7 The Iliad meets Troy 8 Based on, adapted, inspired – levels of intertextuality 8 Different mediums of expression 11 Mutations of the Iliad in Troy 14 The beginning 14 The middle 16 The end 18 Greece vs. Troy = USA vs. Iraq? Possible Allegories 20 Historical ties 21 The nobility of war 22 Defining a hero 25 Metamorphosis of an ancient hero through time 26 The environment of breeding heroes 28 Achilles 29 A torn hero 31 Hector 33 Are Gods dead? 36 Conclusions 39 List of works cited 41 Introduction Ancient Greek culture, with its myths, philosophical schools, wars, means of warfare, had always a big appeal factor on me. I was always fascinated by the grade of impact that ancient Greek culture still has on us – contemporary people. How did it travel through time? How is it that the wars we fight today co closely resemble those of 3000 years ago? While weaving ideas for this paper I thought of means of putting the ancient and the modern together. To find a binding material for two cultural products separated by thousands of years – Homer‟s the Iliad and Wolfgang Petersen‟s film Troy. The main task for me in this paper is to see the “travel of ideas and values” from the Iliad to Troy.