Resuscitation Resuscitation on Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London. -

Dominique Moore

14 City Lofts 112-116 Tabernacle Street London EC2A 4LE offi[email protected] +44 (0) 20 7734 6441 DOMINIQUE MOORE Finding Alice (ITV) A Confession (ITV) Four Weddings & A Funeral (Hulu) Television Role Title Production Company Director Producer, Tracey Soph EMILY ATACK SHOW Monkey Kingdom Tommy Forbes Yasmina (Series Regular) FINDING ALICE Bright Pictures / ITV Roger Goldby Steph Walker ANTHONY LA Productions / BBC Terry McDonough Yvette ENTERPRICE Fudge Park / BBC3 Ella Jones Rosie FOUR WEDDINGS & A FUNERAL MGM / Hulu Tristram Shapeero Miss X A CONFESSION ITV Paul Andrew Williams Mrs Connor CREEPED OUT (SEASON 2) Netflix Gareth Tunley Shirley TORVIL & DEAN ITV Gillies Mackinnon Journalist URBAN MYTH: THE TRIAL OF King Bert for Sky Arts Elliot Hegarty JOAN COLLINS Various TRACEY BREAKS THE NEWS BBC Dominic Brigstocke (SERIES 2) Serena MURDER IN SUCCESSVILLE Tiger Aspect James De Fond Rosie QUACKS Lucky Giant Andy De Emmony Various TRACEY BREAKS THE NEWS BBC Dominic Brigstocke (SERIES 1) Chelsea HENRY IX Retort Vadim Jean Various TRACEY ULLMAN’S SHOW BBC Nick Collett Ankita RED DWARF Baby Cow Productions Doug Naylor Yvette OBSESSION DARK DESIRES October Films Jonathan Davenport Cleopatra / Victorian Woman GORY GAMES Lion Television Dominic Brigstocke Various HORRIBLE HISTORIES SPECIALS Lion Television Steve Connelly Annie DRIFTERS (SEASON 2) Bwark Tom Marshall Zara HOLBY CITY BBC Griff Rowland Lottie THE JOB LOT (SEASON 2) Big Talk Productions Luke Snellin Marion THE MIMIC (SEASON 2) Running Bare Productions / Kieron Hawkes Channel 4 Julie POND -

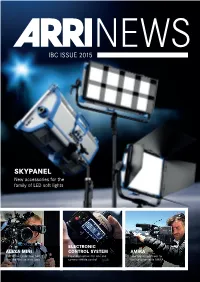

SKYPANEL New Accessories for the Family of LED Soft Lights

NEWS IBC ISSUE 2015 SKYPANEL New accessories for the family of LED soft lights ELECTRONIC ALEXA MINI CONTROL SYSTEM AMIRA Karl Walter Lindenlaub ASC, BVK Expanded options for lens and New application areas for tries the Mini on Nine Lives camera remote control the highly versatile AMIRA EDITORIAL DEAR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES We hope you can join postproduction through ARRI Media, illustrating us here at IBC, where we the uniquely broad range of products and services are showcasing our latest we offer. 18 camera systems and lighting technologies. For the ARRI Rental has also been busy supplying the first time in ARRI News we are also introducing our ALEXA 65 system to top DPs on major feature films newest business unit: ARRI Medical. Harnessing – many are testing the large-format camera for the core imaging technology and reliability of selected sequences and then opting to use it on ALEXA, our ARRISCOPE digital surgical microscope main unit throughout production. In April IMAX is already at work in operating theaters, delivering announced that it had chosen ALEXA 65 as the unsurpassed 3D images of surgical procedures. digital platform for 2D IMAX productions. In this issue we share news of how AMIRA is Our new SkyPanel LED soft lights, announced 12 being put to use on productions so diverse and earlier this year and shipping now as promised, are wide-ranging that it has taken even us by surprise. proving extremely popular and at IBC we are The same is true of the ALEXA Mini, which was unveiling a full selection of accessories that will introduced at NAB and has been enthusiastically make them even more flexible. -

Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition

The MGB Challenge Evaluating Multi-Genre Broadcast Media Recognition Peter Bell, Jonathan Kilgour, Steve Renals, Mirjam Wester University of Edinburgh Mark Gales, Pierre Lanchantin, Xunying Liu, Phil Woodland University of Cambridge Thomas Hain, Oscar Saz University of Sheffield Andrew McParland BBC R&D mgb-challenge.org Overview Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Overview Establish an open challenge in core ASR research with common data and evaluation benchmarks on broadcast data Controlled evaluation of speech recognition, speaker diarization, and alignment Using a broad, multi-genre dataset of BBC TV output Subtitles & light supervision • Training data transcribed by subtitles (closed captions) – can differ from verbatim transcripts • edits to enhance clarity • paraphrasing • deletions where the speech is too fast • There may be • words in the subtitles that were not spoken • words missing in the subtitles that were spoken • Additional metadata includes speaker change information, timestamps, genre tags, … MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs MGB Resources Fixed acoustic and language model training data – precise comparison of models and algorithms – data made available by BBC R&D Labs • Acoustic model training 1600h broadcast audio across 4 BBC channels (1 April – 20 May 2008), with as-broadcast subtitles – ~33% WER (26% deletions) • Language model -

Sci-Fi Sisters with Attitude Television September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE!

April 2021 Sky’s Intergalactic: Sci-fi sisters with attitude Television www.rts.org.uk September 2013 1 LOVE TV? SO DO WE! R o y a l T e l e v i s i o n S o c i e t y b u r s a r i e s o f f e r f i n a n c i a l s u p p o r t a n d m e n t o r i n g t o p e o p l e s t u d y i n g : TTEELLEEVVIISSIIOONN PPRROODDUUCCTTIIOONN JJOOUURRNNAALLIISSMM EENNGGIINNEEEERRIINNGG CCOOMMPPUUTTEERR SSCCIIEENNCCEE PPHHYYSSIICCSS MMAATTHHSS F i r s t y e a r a n d s o o n - t o - b e s t u d e n t s s t u d y i n g r e l e v a n t u n d e r g r a d u a t e a n d H N D c o u r s e s a t L e v e l 5 o r 6 a r e e n c o u r a g e d t o a p p l y . F i n d o u t m o r e a t r t s . o r g . u k / b u r s a r i e s # R T S B u r s a r i e s Journal of The Royal Television Society April 2021 l Volume 58/4 From the CEO It’s been all systems winners were “an incredibly diverse” Finally, I am delighted to announce go this past month selection. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

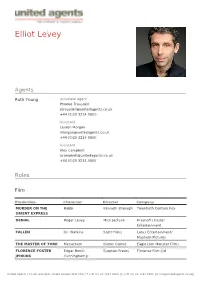

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

Casualty-S31-Ep44-One.Pdf

I have tried to show when we are in another LOCATION by using BOLD CAPITALS. I have used DUAL DIALOGUE as people talk over each other on a SINGLE SHOT. From the beginning - for the next hour - everything about ONE is to do with the inexorability of things in life and A+E. Time cannot be reversed, events cannot be interrupted. Like life. FIRST FLOOR OF SMALL HOUSE... Absolute stillness. At first we can’t work out what we are looking at. Just the green numbers of a digital alarm clock - 14.21. A horizontal slither of light, smudging with smoke. Somewhere close a baby gurgles and then coughs. Things are starting to get clearer. Then we hear JEZ shouting and coughing. JEZ(O.O.V) Hello? You in here... Hello? * You in here? * Hello! * She’s here! She’s ... * I got you. It’s OK. * Anyone there? Anyone... * I got her. I got her! * IAIN Was anyone else in there? You listening to me? Anyone else in there? JEZ * No! I shouted. Looked everywhere. No. SUN-MI * Leave me alone. I am OK. I want my * daughter. IAIN * Do you speak English? What’s your name? Miss? SUN-MI (in KOREAN) I want my daughter. JEZ What’s she saying? IAIN I don’t know. Let’s get her on O2 and check her Obs, yes, Jez? Episode 45 - SHOOTING SCRIPT 'One' 1. Casualty 31 Episode 45 - JEZ She was unresponsive when I got to her. Sorry, Iain. * IAIN * Late to the party again, boys. * Superman himself here... ... saw her at the window. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

PITCHING in Exclusive U.S

For Your Consideration Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Limited Series or Television Movie – Hayley Mills New BBC Wales, BBC One and Acorn TV Original Series Larry Lamb (EastEnders, New Tricks) and Hayley Mills (The Parent Trap) star in new family drama series set in picturesque Wales PITCHING IN Exclusive U.S. Premiere on Acorn TV on Friday, May 24, 2019 (Memorial Day Weekend) The newest heartwarming drama from Acorn TV and BBC Wales, PITCHING IN makes its exclusive U.S. Premiere on Acorn TV on Friday, May 24, 2019 (Memorial Day Weekend). Written by writing duo Johanne McAndrew and Elliot Hope (Candy Cabs, Holby City), Pitching In stars beloved British actor Larry Lamb (New Tricks, EastEnders, Gavin & Stacey, Murphy’s Law) as Frank Hardcastle, a man who runs a holiday park on the idyllic North Wales coast and finds his peace and quiet disrupted when his flighty daughter (Caroline Sheen) and grandson move back home. Filmed entirely on location in Anglesey in beautiful Wales, the 4-part series also stars the charming, Oscar and Golden Globe winning actress Hayley Mills (The Parent Trap, Pollyanna, Wild at Heart) and Melanie Walters (Gavin & Stacey). Called a “glorious streaming service… an essential must-have” (The Hollywood Reporter), Acorn TV is North America’s largest streaming service specializing in British and international television. Acorn TV’s UK development arm, Acorn Media Enterprises is the North American co-producer of the series. Recent widower, Frank Hardcastle, is struggling to find the energy or enthusiasm to run Daffodil Dunes Holiday Park in the picturesque North Wales coast.