Affective Partisan Polarization and Moral Dilemmas During the COVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drucksache 19/24635

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/24635 19. Wahlperiode 24.11.2020 Antrag der Abgeordneten Margit Stumpp, Kai Gehring, Dr. Anna Christmann, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Dr. Janosch Dahmen, Erhard Grundl, Dr. Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Ulle Schauws, Charlotte Schneidewind-Hartnagel, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Annalena Baerbock, Ekin Deligöz, Markus Kurth, Sven Lehmann, Claudia Müller, Beate Müller- Gemmeke, Lisa Paus, Corinna Rüffer und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Bildungschancen gewährleisten, Kinder und Beschäftigte schützen und das Infektionsgeschehen eindämmen – Förderprogramm für mobile Luftfilter in Klassenräumen und Kindertageseinrichtungen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Der erste Lockdown hat offenbart, wie sehr Bildungschancen und ein für Kinder wich- tiges Sozialgefüge eingeschränkt werden, wenn Bildungs- und Betreuungseinrichtun- gen geschlossen werden. Obwohl mit einer Verschärfung der Infektionslage im Herbst und Winter gerechnet werden konnte, wurde vielerorts zu wenig getan, um wichtige Bereiche wie Bildungseinrichtungen bei der Vorbereitung auf diese Phase zu unter- stützen und vorzubereiten. Um das Infektionsrisiko für Kinder, Jugendliche, Betreue- rInnen und LehrerInnen zu reduzieren, braucht es ein ganzes Set von Maßnahmen. Mit der Verengung auf Einzelmaßnahmen wird ein angemessenes Schutzniveau nicht zu erreichen sein. Nun müssen deshalb mit hohem Tempo alle Möglichkeiten ausge- schöpft werden, damit Schulen und Kitas auch im weiteren Verlauf der Pandemie weit- -

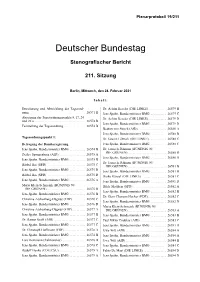

Plenarprotokoll 19/211

Plenarprotokoll 19/211 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 211. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 24. Februar 2021 Inhalt: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Dr. Achim Kessler (DIE LINKE) . 26579 B nung . 26571 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26579 C Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 8, 17, 24 Dr. Achim Kessler (DIE LINKE) . 26579 D und 26 o . 26574 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26579 D Feststellung der Tagesordnung . 26574 B Beatrix von Storch (AfD) . 26580 A Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26580 B Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Dr. Gesine Lötzsch (DIE LINKE) . 26580 C Befragung der Bundesregierung Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26580 C Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26574 B Dr. Janosch Dahmen (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 26580 D Detlev Spangenberg (AfD) . 26575 A Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26580 D Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26575 B Dr. Janosch Dahmen (BÜNDNIS 90/ Bärbel Bas (SPD) . 26575 C DIE GRÜNEN) . 26581 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26575 D Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26581 B Bärbel Bas (SPD) . 26575 D Heike Hänsel (DIE LINKE) . 26581 C Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26576 A Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26581 D Maria Klein-Schmeink (BÜNDNIS 90/ Hilde Mattheis (SPD) . 26582 A DIE GRÜNEN) . 26576 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26582 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26576 B Dr. Gero Clemens Hocker (FDP) . 26582 C Christine Aschenberg-Dugnus (FDP) . 26576 C Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26582 D Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26576 D Maria Klein-Schmeink (BÜNDNIS 90/ Christine Aschenberg-Dugnus (FDP) . 26577 A DIE GRÜNEN) . 26583 A Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26577 B Jens Spahn, Bundesminister BMG . 26583 B Dr. Rainer Kraft (AfD) . 26577 C Paul Viktor Podolay (AfD) . -

Antrag Gemäß Art. 93 Abs.1 Nr. 2 Grundgesetz

Professor Dr. Dieter Dörr An das Bundesverfassungsgericht – Erster Senat – Schlossbezirk 3 76131 Karlsruhe Saarbrücken, 22.06.2021 Antrag gemäß Art. 93 Abs.1 Nr. 2 Grundgesetz der Bundestagsabgeordneten Doris Achelwilm Fraktion DIE LINKE und der nachfolgend aufgeführten weiteren 212 Abgeordneten des Deutschen Bun- destages 1. Grigorios Aggelidis FDP Fraktion 2. Gökay Akbulut Fraktion DIE LINKE 3. Renata Alt FDP Fraktion 4. Luise Amtsberg Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 5. Christine Aschenberg-Dugnus FDP Fraktion 6. Lisa Badum Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 7. Annalena Baerbock Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 8. Simone Barrientos Fraktion DIE LINKE 9. Dr. Dietmar Bartsch Fraktion DIE LINKE 10. Nicole Bauer FDP Fraktion 11. Margarete Bause Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 12. Canan Bayram Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 13. Jens Beeck FDP Fraktion 14. Lorenz Gösta Beutin Fraktion DIE LINKE 15. Matthias W. Birkwald Fraktion DIE LINKE 16. Heidrun Bluhm-Förster Fraktion DIE LINKE 17. Dr. Jens Brandenburg FDP Fraktion 18. Mario Brandenburg FDP Fraktion 19. Michel Brandt Fraktion DIE LINKE 20. Dr. Franziska Brantner Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 21. Agnieszka Brugger Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 22. Sandra Bubendorfer-Licht FDP Fraktion 23. Christine Buchholz Fraktion DIE LINKE 24. Dr. Birke Bull-Bischoff Fraktion DIE LINKE 25. Dr. Marco Buschmann FDP Fraktion 26. Karlheinz Busen FDP Fraktion 27. Jörg Cezanne Fraktion DIE LINKE 28. Dr. Anna Christmann Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 29. Carl-Julius Cronenberg FDP Fraktion 30. Sevim Dağdelen Fraktion DIE LINKE 31. Dr. Janosch Dahmen Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 32. Britta Katharina Dassler FDP Fraktion 33. Fabio De Masi Fraktion DIE LINKE 34. -

20210421 6-Data.Pdf

Deutscher Bundestag 223. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Mittwoch, 21. April 2021 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 6 Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD Entwurf eines Vierten Gesetzes zum Schutz der Bevölkerung bei einer epidemischen Lage von nationaler Tragweite - Drs. 19/28444, 19/28692 und 19/28732 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 656 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 53 Ja-Stimmen: 342 Nein-Stimmen: 250 Enthaltungen: 64 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 21.04.2021 Beginn: 14:53 Ende: 15:27 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Dr. Michael von Abercron X Stephan Albani X Norbert Maria Altenkamp X Peter Altmaier X Philipp Amthor X Artur Auernhammer X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Melanie Bernstein X Christoph Bernstiel X Peter Beyer X Marc Biadacz X Steffen Bilger X Peter Bleser X Norbert Brackmann X Michael Brand (Fulda) X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Dr. Helge Braun X Silvia Breher X Sebastian Brehm X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Dr. Carsten Brodesser X Gitta Connemann X Astrid Damerow X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Thomas Erndl X Dr. Dr. h. c. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Enak Ferlemann X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Thorsten Frei X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Maika Friemann-Jennert X Michael Frieser X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/224

Plenarprotokoll 19/224 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 224. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 22. April 2021 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 10: sierungsgesetz – Den Schutz von Ver- braucherinnen und Verbrauchern in a) – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von der den Mittelpunkt stellen Bundesregierung eingebrachten Ent- wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Umsetzung – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten der Richtlinie (EU) 2018/1972 des Dr. Konstantin von Notz, Tabea Rößner, Europäischen Parlaments und des Margit Stumpp, weiterer Abgeordneter Rates vom 11. Dezember 2018 über und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE den europäischen Kodex für die elekt- GRÜNEN: Telekommunikationsmo- ronische Kommunikation (Neufas- dernisierungsgesetz – Datenschutz, sung) und zur Modernisierung des IT-Sicherheit und Bürgerrechte Telekommunikationsrechts (Telekom- sichern munikationsmodernisierungsgesetz) Drucksachen 19/26117, 19/26531, Drucksachen 19/26108, 19/26964, 19/26532, 19/26533, 19/28865 . 28401 D 19/27035 Nr. 1.9, 19/28865 . 28401 B d) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des – Bericht des Haushaltsausschusses ge- Ausschusses für Inneres und Heimat zu mäß § 96 der Geschäftsordnung dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Jimmy Drucksache 19/28866 . 28401 B Schulz, Stephan Thomae, Renata Alt, wei- terer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des FDP: Recht auf Verschlüsselung – Pri- Ausschusses für Wirtschaft und Energie vatsphäre und Sicherheit im digitalen – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Raum stärken Reinhard Houben, Manuel Höferlin, Drucksachen 19/5764, 19/27325 . 28401 D Michael Theurer, weiterer Abgeordneter e) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des und der Fraktion der FDP: Gigabit-Aus- Ausschusses für Verkehr und digitale In- bau voranbringen – Upgrade für das frastruktur zu dem Antrag der Abgeordne- Nebenkostenprivileg ten Daniela Kluckert, Frank Sitta, – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Margit Grigorios Aggelidis, weiterer Abgeordne- Stumpp, Tabea Rößner, Dr. -

Drucksache 19/27763

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/27763 19. Wahlperiode 23.03.2021 Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Anja Hajduk, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Markus Kurth, Sven Lehmann, Corinna Rffer, Claudia Müller, Lisa Paus, Stefan Schmidt, Dr. Janosch Dahmen, Kai Gehring, Britta Haßelmann, Dr. Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Charlotte Schneidewind-Hartnagel, Margit Stumpp, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Arbeitsfrderung in der Krise – Für einen besseren Einstieg Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Im internationalen Vergleich steht der Arbeitsmarkt in Deutschland in der Coronakrise verhältnismäßig gut da. Das liegt vor allem am Instrument der Kurzarbeit, mit dem noch immer Entlassungen grßeren Ausmaßes verhindert werden konnten. Allerdings werden auch in Deutschland während der Corona-Pandemie weniger Menschen neu eingestellt, was der Hauptgrund fr den Anstieg der Arbeitslosigkeit in Deutschland ist. So ist die Zahl der angebotenen Stellen im Juli 2020 um 28 Prozent, also ein Drittel gegenber dem Vorjahr, gesunken (vgl. Bundesagentur fr Arbeit August 2020 Mo- natsbericht zu den Arbeitsmarktzahlen, S. 10). In allen Personengruppen fanden weniger Menschen einen neuen Job. Doch besonders betroffen davon sind durch die Corona-Krise junge Menschen und insbesondere Ab- solventinnen und Absolventen, die gerade ihre Ausbildung oder das Studium beendet haben. Angesichts der konjunkturellen schwierigen Lage ist laut einer Analyse des FIBS mit einem längerfristigen Anstieg der Jugendarbeitslosigkeit um 18 Prozent im Vergleich zu 2019 zu rechnen (vgl. FiBS Forum Oktober 2020 Jugendarbeitslosigkeit in Deutschland, S. 7). Deutschland hat in Europa eine vergleichsweise geringe Jugend- arbeitslosigkeit, aber bereits jetzt ist die Gruppe der jugendlichen Arbeitssuchenden unter 25 die am schnellsten wachsende Altersgruppe unter den Arbeitslosen. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 223. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Mittwoch, 21. April 2021 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 5 Änderungsantrag der Abgeordneten Kordula Schulz-Asche, Dr. Janosch Dahmen, Maria Klein-Schmeink, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDINS 90/DIE GRÜNEN zu der zweiten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD - Drucksachen 19/28444, 19/28692, 19/28732, 19/28760 - Entwurf eines Vierten Gesetzes zum Schutz der Bevölkerung bei einer epidemischen Lage von nationaler Tragweite Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 652 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 57 Ja-Stimmen: 117 Nein-Stimmen: 457 Enthaltungen: 78 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 21.04.2021 Beginn: 13:47 Ende: 14:19 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Dr. Michael von Abercron X Stephan Albani X Norbert Maria Altenkamp X Peter Altmaier X Philipp Amthor X Artur Auernhammer X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Melanie Bernstein X Christoph Bernstiel X Peter Beyer X Marc Biadacz X Steffen Bilger X Peter Bleser X Norbert Brackmann X Michael Brand (Fulda) X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Dr. Helge Braun X Silvia Breher X Sebastian Brehm X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Dr. Carsten Brodesser X Gitta Connemann X Astrid Damerow X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Thomas Erndl X Dr. Dr. h. c. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Enak Ferlemann X Axel E. -

20210611 2-Data.Pdf

Deutscher Bundestag 234. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 11. Juni 2021 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 2 Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD Feststellung des Fortbestehens der epidemischen Lage von nationaler Tragweite Drs. 19/30398 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 599 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 110 Ja-Stimmen: 375 Nein-Stimmen: 218 Enthaltungen: 6 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 11.06.2021 Beginn: 14:32 Ende: 15:02 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Dr. Michael von Abercron X Stephan Albani X Norbert Maria Altenkamp X Peter Altmaier X Philipp Amthor X Artur Auernhammer X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Melanie Bernstein X Christoph Bernstiel X Peter Beyer X Marc Biadacz X Steffen Bilger X Peter Bleser X Norbert Brackmann X Michael Brand (Fulda) X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Dr. Helge Braun X Silvia Breher X Sebastian Brehm X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Dr. Carsten Brodesser X Gitta Connemann X Astrid Damerow X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Thomas Erndl X Dr. Dr. h. c. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Enak Ferlemann X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Thorsten Frei X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Maika Friemann-Jennert X Michael Frieser X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. Thomas Gebhart X Seite: 3 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. -

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/24436 19. Wahlperiode 18.11.2020 Vorabfassung - wird durch die lektorierte Fassung ersetzt. Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Dr. Janosch Dahmen, Bettina Hoff- mann, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Kordula Schulze-Asche, Dr. Anna Christmann, Kai Gehring, Erhard Grundl, Ulle Schauws, Charlotte Schneidewind-Hartnagel, Margit Stumpp, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Britta Haßelmann, Sven-Christan Kindler, Mar- kus Kurth, Sven Lehmann, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Lisa Paus, Corinna Rüffer, Stefan Schmidt und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Den Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienst dauerhaft stärken, die Public Health-Perspektive in unserem Gesundheitswesen ausbauen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Die Covid-19-Pandemie zeigt, dass Gesundheit weit mehr ist als ein individuelles Geschehen. Die Corona-Krise ist – wie andere Pandemien, Epidemien oder Volkskrankheiten auch – mit einem rein individualmedizinischen, kurativen An- satz nicht zu bewältigen. Vielmehr spielen hierbei Maßnahmen zum verbesserten Infektionsschutz und zur Hygiene sowie die Stärkung von Ressourcen und Ver- besserung von Gesundheitschancen eine herausragende Rolle. Die öffentliche Sorge um die Gesundheit aller (Public Health) ist nicht nur der Schlüssel zur Be- wältigung der aktuellen Corona-Pandemie, sondern ein zukunftsweisender Schlüssel für mehr Gesundheitsschutz und Gesundheitsförderung der gesamten Bevölkerung. Den breiten Aufgabenkreis aus Gesundheitsschutz der Bevölkerung, Gesund- heitsförderung und -

Weihnachtsappell Für Eine Humanitäre Aufnahme Geflüchteter Von Den Griechischen Inseln

Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages Weihnachtsappell für eine humanitäre Aufnahme Geflüchteter von den griechischen Inseln In der Nacht vom 8. auf den 9. September 2020 wurde das Flüchtlingslager Moria auf der griechischen Insel Lesbos durch einen Brand zerstört. Bereits zuvor war das Lager Moria über Jahre zum Symbol des Versagens europäischer Asylpolitik geworden: Zeitweise mussten über 20.000 Menschen in einem Camp ausharren, das für 3.000 Menschen ausgerichtet war. Die Versorgungs- und Hygienesituation war katastrophal. Deutschland hat auf diese Situation gemeinsam mit anderen europäischen Ländern reagiert, Hilfsgüter entsandt und die Aufnahmezusage auf knapp 3.000 Menschen erhöht. Dennoch leben die Menschen auch drei Monate nach dem Brand immer noch unter menschenunwürdigen Bedingungen auf den griechischen Inseln oder auf dem Festland. Die humanitäre Situation im neuen Übergangslager Kara Tepe ist laut übereinstimmenden Berichten von Menschenrechtsorganisationen deutlich schlechter als im Camp Moria: Die Unterkünfte sind nicht winterfest, immer noch gibt es keine ausreichende sanitäre Versorgung – Duschen und Toiletten fehlen vielfach. Gewaltsame Übergriffe auch gegen besonders Schutzbedürftige sind an der Tagesordnung. Unter diesen Bedingungen leiden besonders die vielen Kinder. Angesichts dieser Zustände kritisieren wir umso mehr, dass humane Aufnahmestrukturen wie das auf Lesbos betriebene Flüchtlingslager „PIKPA“ für besonders schutzbedürftige Menschen aufgelöst wurden. Uns ist bewusst, dass nur ein Gemeinsames Europäisches -

Antrag Von BÜNDNIS 90

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/27830 19. Wahlperiode 23.03.2021 Antrag der Abgeordneten Maria Klein-Schmeink, Dr. Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Kordula Schulz-Asche, Dr. Janosch Dahmen, Dr. Anna Christmann, Kai Gehring, Erhard Grundl, Ulle Schauws, Charlotte Schneidewind-Hartnagel, Margit Stumpp, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Sven-Christian Kindler, Sven Lehmann, Lisa Paus, Corinna Rffer, Stefan Schmidt und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Mehr Verlässlichkeit und Qualität in der stationären Krankenhausversorgung – Vergtungssystem, Investitionsfinanzierung und Planung reformieren Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Krankenhäuser gehren zur gesundheitlichen Daseinsvorsorge. Menschen, die auf me- dizinische Hilfe angewiesen sind, mssen sich – unabhängig davon, wo sie leben und in welcher sozialen Lage sie sich befinden – auf ein verlässliches und qualitativ hoch- wertiges Versorgungssystem verlassen können. Auch wenn wir in Deutschland insge- samt ein gutes Versorgungssystem haben, gibt es deutliche regionale Unterschiede hinsichtlich der Erreichbarkeit und der Qualität des nächstgelegenen Krankenhauses. In einigen Regionen gibt es Versorgungslcken in bestimmten Disziplinen, in anderen eine Über- und Fehlversorgung mit einer nicht bedarfsgerechten Anzahl und Vertei- lung von Krankenhausstandorten und -betten. Übergänge vom Krankenhaus zu nach- gelagerten Versorgungsangeboten, insbesondere auch zur Rehabilitation und der am- bulanten Pflege, erweisen sich immer wieder als problematisch. Der Staat kommt seiner -

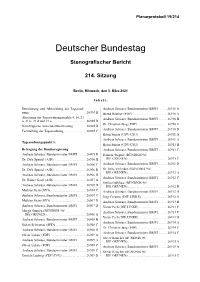

Plenarprotokoll 19/214

Plenarprotokoll 19/214 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 214. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 3. März 2021 Inhalt: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26910 A nung . 26903 B Bernd Reuther (FDP) . 26910 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 4, 14, 21 Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26910 B a, 21 b, 21 d und 21 e . 26905 B Dr. Christian Jung (FDP) . 26910 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 26905 B Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26910 D Feststellung der Tagesordnung . 26905 C Björn Simon (CDU/CSU) . 26911 A Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26911 A Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Björn Simon (CDU/CSU) . 26911 B Befragung der Bundesregierung Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26911 C Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26905 D Daniela Wagner (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dr. Dirk Spaniel (AfD) . 26906 B DIE GRÜNEN) . 26911 C Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26906 C Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26911 D Dr. Dirk Spaniel (AfD) . 26906 D Dr. Julia Verlinden (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 26912 A Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26906 D Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26912 C Dr. Rainer Kraft (AfD) . 26907 A Stefan Gelbhaar (BÜNDNIS 90/ Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26907 B DIE GRÜNEN) . 26912 D Mathias Stein (SPD) . 26907 C Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26912 D Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26907 C Jörg Cezanne (DIE LINKE) . 26913 A Mathias Stein (SPD) . 26907 D Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26913 B Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26907 D Victor Perli (DIE LINKE) . 26913 C Margit Stumpp (BÜNDNIS 90/ Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26913 C DIE GRÜNEN) . 26908 A Victor Perli (DIE LINKE) . 26913 D Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI . 26908 B Andreas Scheuer, Bundesminister BMVI .