SKY's RESPONSE to OFCOM's REVIEW of the PAY TV WHOLESALE MUST-OFFER OBLIGATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. There Is No Need To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript of Hearing (Day 3)

1 Wednesday, 5 October 2016 2 (10.30 am) 3 THE CHAIRMAN: Good morning, Mr Beard. 4 MR BEARD: Mr Chairman, members of the tribunal, we are 5 moving on to factual evidence, and the first witness to 6 be called is Mr John Petter. 7 MR JOHN RICHARD MARTIN PETTER (sworn) 8 Examination-in-chief by MR BEARD 9 MR BEARD: Mr Petter, good morning. First of all, you 10 should have in front of you a set of bundles -- ah, they 11 are behind. That is a good start. 12 Those bundles, just for the tribunal's information, 13 should contain material that is confidential to BT. It 14 is obviously not material that is confidential to other 15 parties. So some of the redactions will be different 16 from the material you have before you. 17 Could you be passed bundle N1, or core 1, depending 18 on how it is labelled. If you could turn to tab B, 19 there is a document that, on the first page, is said to 20 be a witness statement of Mr John Richard Martin Petter. 21 If you turn to the back of that document, do you have 22 a signature page? 23 A. Yes, I do, page 79. 24 Q. Is this your witness statement? 25 A. That's right, it is, yes. 1 1 Q. Just for the tribunal's note, the versions you have 2 won't have a signature on the back page because, when 3 the confidentiality marking was done, it was done on an 4 electronic version? 5 THE CHAIRMAN: You will be pleased to know that I do have 6 a signature page. -

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

Download Report

cover_final_02:Layout 1 20/3/14 13:26 Page 1 Internet Watch Foundation Suite 7310 First Floor Building 7300 INTERNET Cambridge Research Park Waterbeach Cambridge WATCH CB25 9TN United Kingdom FOUNDATION E: [email protected] T: +44 (0) 1223 20 30 30 ANNUAL F: +44 (0) 1223 86 12 15 & CHARITY iwf.org.uk Facebook: Internet Watch Foundation REPORT Twitter: @IWFhotline. 2013 Internet Watch Foundation Charity number: 1112 398 Company number: 3426 366 Internet Watch Limited Company number: 3257 438 Design and print sponsored by cover_final_02:Layout 1 20/3/14 13:26 Page 2 OUR VISION: TO ELIMINATE ONLINE CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE IMAGES AND VIDEOS To help us achieve this goal we work with the following operational partners: OUR MEMBERS: Our Members help us remove and disrupt the distribution of online images and videos of child sexual abuse. It is with thanks to our Members for their support that we are able to do this work. As at December 2013 we had 110 Members, largely from the online industry. These include ISPs, mobile network operators, filtering providers, search providers, content providers, and the financial sector. POLICE: In the UK we work closely with the “This has been a hugely important year for National Crime Agency CEOP child safety online and the IWF have played a Command. This partnership allows us vital role in progress made. to take action quickly against UK-hosted criminal content. We also Thanks to the efforts of the IWF and their close work with international law working with industry and the NCA, enforcement agencies to take action against child sexual abuse content hosted anywhere in the world. -

Talktalk Telecom Group Limited Annual Report 2021 1 STRATEGIC REPORT Our Business Model

TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited 2021 Annual Report 2021 Annual Limited Group Telecom TalkTalk 2021 ANNUAL REPORT TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited (formerly TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC) At a glance Contents Strategic report IFC At a glance 2 Our business model 4 Our strategy 6 Key performance indicators 8 Business and financial review 13 Principal risks and uncertainties HQ 18 Section 172 Salford, Greater 24 Regulatory environment Manchester 26 Corporate social responsibility Corporate governance 30 Corporate governance 35 Audit Committee report 38 Directors’ remuneration report 53 Directors’ report 55 Directors’ responsibility statement 47,300 Financial statements Over 3,000 high-speed unbundled 56 Independent auditor’s report Ethernet 66 Consolidated income statement exchanges 67 Consolidated balance sheet connections 68 Consolidated cash flow statement 69 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 70 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 108 Company balance sheet 109 Company cash flow statement 110 Company statement of changes in equity 111 Notes to the Company financial statements Other information UK’s 116 Five year record (unaudited) 96% largest 117 Alternative performance measures population wholesale 118 Glossary coverage broadband 120 Registered office 120 Advisers provider Over 957 million GB average 4 million customer broadband downloads per customers month Stay up to date at www.talktalkgroup.com 2,019 2.8 million employees FTTC and FTTP (as at 28 customers February 2021) WHO WE ARE TalkTalk is the UK’s leading value for money connectivity provider. We believe that simple, affordable, reliable and fair connectivity should be available to everyone. Since entering the market in the early 2000s, we have a proud history as an innovative challenger brand ensuring customers benefit from more choice, affordable prices and better services. -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

PCCW Limited ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT for the YEAR

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. PCCW Limited (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) (Stock Code: 0008) ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The directors (“Directors”) of PCCW Limited (“PCCW” or the “Company”) hereby announce the audited consolidated results of the Company and its subsidiaries (collectively the “Group”) for the year ended December 31, 2020. Consolidated revenue increased by 1% to HK$38,046 million Consolidated revenue, excluding Mobile product sales, up 4% to HK$35,437 million HKT total revenue, excluding Mobile product sales, was stable at HK$29,780 million6 Now TV revenue down 6% to HK$2,512 million7 OTT revenue up 11% to HK$1,187 million, underpinned by 20% growth in video revenue Free TV & related business revenue up 22% to HK$317 million Solutions business revenue up 12% to HK$4,736 million PCPD revenue up 82% to HK$1,843 million Consolidated EBITDA decreased by 3% to HK$11,978 million due to decline in roaming and Solutions business EBITDA in the midst of the pandemic, which was partially offset by steady performance of Now TV and improved results at OTT and Free TV businesses Consolidated loss attributable to equity holders of the -

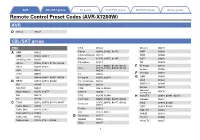

Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR

AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR D Denon 73347 CBL/SAT group CBL CCS 03322 Director 00476 A ABN 03322 Celrun 02959, 03196, 03442 DMT 03036 ADB 01927, 02254 Channel Master 03118 DSD 03340 Alcatel-Lucent 02901 Charter 01376, 01877, 02187 DST 03389 Amino 01602, 01481, 01822, 02482 Chunghwa 01917 DV 02979 Arion 03034, 03336 01877, 00858, 01982, 02345, E Echostar 03452 Cisco 02378, 02563, 03028, 03265, Arris 02187 03294 Entone 02302 AT&T 00858 CJ 03322 F Freebox 01976 au 03444, 03445, 03485, 03534 CJ Digital 02693, 02979 G GBN 03407 B BBTV 02516, 02518, 02980 CJ HelloVision 03322 GCS 03322 Bell 01998 ClubInternet 02132 GDCATV 02980 BIG.BOX 03465 CMB 02979, 03389 Gehua 00476 General Bright House 01376, 01877 CMBTV 03498 Instrument 00476 BSI 02979 CNS 02350, 02980 H Hana TV 02681, 02881, 02959 BT 02294 Com Hem 00660, 01666, 02015, 02832 Handan 03524 C C&M 02962, 02979, 03319, 03407 01376, 00476, 01877, 01982, HCN 02979, 03340 Comcast 02187 Cable Magico 03035 HDT 02959, 03465 Coship 03318 Cable One 01376, 01877 Hello TV 03322 Cox 01376, 01877 Cable&Wireless 01068 HelloD 02979 Daeryung 01877 Cablecom 01582 D Hi-DTV 03500 DASAN 02683 Cablevision 01376, 01877, 03336 Hikari TV 03237 Digeo 02187 1 AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Homecast 02977, 02979, 03389 02692, 02979, 03196, 03340, 01982, 02703, 02752, 03474, L LG 03389, 03406, 03407, 03500 Panasonic 03475 Huawei 01991 LG U+ 02682, 03196 Philips 01582, 02174, 02294 00660, 01981, 01983, -

Analysys Mason Document

Sky launches a mobile service in the UK in anticipation of increased competition in convergence December 2016 Heenu Nihalani and Kerem Arsal Sky is the newest entrant to the UK mobile market, and the forthcoming launch of its ‘Sky Mobile’ service brings an alternative fixed–mobile proposition to a relatively nascent convergence market. As a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO), it will use O2’s network, and offer 12-month contracts in loose bundles to its fixed subscribers, as well as separately to non-subscribers at a higher price point. Sky reports that over 46 000 people have pre-registered for Sky Mobile, which will be launched in mid-December. This article examines Sky Mobile’s pricing and positioning in more detail, and discusses the effects that this service may have on the UK’s mobile and FMC markets. Sky is clearly targeting its mobile proposition at its current customer base Sky is entering the market with relatively cautious pricing, without aggressive discounting, and with continued focus on premium services. It is a convincing offer for its fixed broadband subscribers, but less so for non- subscribers. The service is positioned to compete in a marketplace increasingly dominated by converged offers following BT’s acquisition of EE in August 2016. Pricing for Sky’s fixed customers is competitive. Prices are tiered around data allowances: GBP10 per month for 1GB, GBP15 for 3GB, and GBP20 for 5GB; each comes with unlimited voice and SMS. The pricing closely matches similar plans from Virgin Media and Vodafone, while BT’s pricing is slightly lower for its FMC bundle subscribers. -

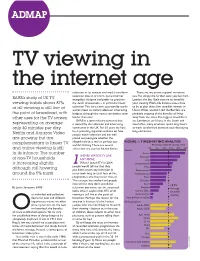

TV Viewing in the Internet Age Television As Its Content and Would Transform There Are Important Regional Variations Television Into an Art Form

TV viewing in the internet age television as its content and would transform There are important regional variations television into an art form. Some internet too. Put simply, the further away you live from BARB’s study of UK TV evangelists disagree and prefer to proclaim London, the less likely you are to timeshift viewing habits shows 87% the death of television – in particular, linear your viewing. Work–life balance issues have of all viewing is still live at television. This isn’t a new assertion by media to be at play: those low timeshift viewers in owners keen to attract television advertising Ulster, Wales, Scotland and the Borders are the point of broadcast, with budgets, although the voices sometimes seem probably enjoying all the benefits of living other uses for the TV screen louder than ever. away from the cities. The biggest timeshifters BARB is a joint industry currency that are Londoners and those in the South and representing on average is owned by the television and advertising South-East, many of whom spend long hours only 40 minutes per day. community in the UK. For 35 years we have at work sandwiched between soul-destroying been providing impartial evidence on how long commutes. Netflix and Amazon Video people watch television and are well are growing but are placed to investigate whether the complementary to linear TV alleged malaise is real or perhaps just FIGURE 1: TIMESHIFTING ANALYSIS wishful thinking. There are several Percentage timeshift viewing, 2015 and online viewing is still claims that are used to fan the flames. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Regional Cable TV & Broadband Operators 57 Regional DTH Satellite Pay-TV Operators 77 Regional IPTV & Broadband Operators 90 Regional Broadcasters 99 Regional Digital & Interactive 126 Regional Fixed Service Satellite 161 Regional Broadcasting & Pay-TV Finance 167 Regional Regulation 187 Australia 195 Cambodia 213 China 217 Hong Kong 241 India 266 Indonesia 326 Japan 365 Korea 389 Malaysia 424 Myanmar 443 New Zealand 448 Pakistan 462 Philippines 472 Singapore 500 Sri Lanka 524 Taiwan 543 Thailand 569 Vietnam 590 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1-56 Methodology & Definitions 2 Overview 3-13 Asia Pacific Net New Pay-TV Subscriber Additions (Selected Years) 3 Asia Pacific Pay-TV Subs - Summary Comparison 4 Asia Pacific Pay-TV Industry Revenue Growth 4 China & India - Net New Pay-TV Subscribers (2013) 5 China & India - Cumulative Net New Pay-TV Subscribers (2013-18) 5 Asia Pacific (Ex-China & India), Net New Subscribers (2013) 6 Asia Pacific Ex-China & India - Cumulative Net New Pay-TV Subscribers (2013-18) 8 Economic Growth in Asia (% Real GDP Growth, 2012-2015) 9 Asia Pacific Blended Pay-TV ARPU Dynamics (US$, Monthly) 10 Asia Pacific Pay-TV Advertising (US$ mil.) 10 Asia Pacific Next Generation DTV Deployment 11 Leading Markets for VAS Services (By Revenue, 2023) 12 Asia Pacific Broadband Deployment 12 Asia Pacific Pay-TV Distribution Market Share (2013) 13 Market Projections (2007-2023) 14-41 Population (000) 14 Total Households (000) 14 TV Homes (000) 14 TV Penetration of Total Households (%) -

Virgin Media Consolidated Financial Statements

Consolidated Financial Statements December 31, 2018 VIRGIN MEDIA INC. 1550 Wewatta Street, Suite 1000 Denver, Colorado 80202 United States VIRGIN MEDIA INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Number Part I: Forward-looking Statements...................................................................................................................................... I - 1 Business ..................................................................................................................................................................... I - 3 Management............................................................................................................................................................... I - 21 Principal Shareholder................................................................................................................................................. I - 23 Risk Factors ............................................................................................................................................................... I - 24 Part II: Independent Auditors’ Report.................................................................................................................................... II - 1 Consolidated Balance Sheets as of December 31, 2018 and 2017 ............................................................................ II - 3 Consolidated Statements of Operations for the Years Ended December 31, 2018, 2017 and 2016 .......................... II - 5 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive -

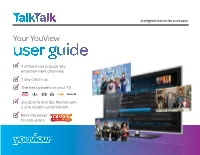

Your Youview User Guide

A brighter home for everyone Your YouView user guide 7 of the most popular Sky entertainment channels 7 day catch-up The best players on your TV Sky Sports and Sky Movies with a one month commitment Rent the latest blockbusters Dip in and out of What’s inside? Sky Sports and Sky Movies Main features 5-7 one month at a time YouView Guide 8-13 Browse and search programmes in the YouView Guide 8 Record 10 Extra channels 13 On Demand 14-19 Catch up on your TV 14 The TalkTalk Player 16 Renting films and adding Boosts 18 Your TalkTalk PIN 19 More information 21-27 Parental controls 21 5 channels for £30 a month 11 channels for £15 a month Now included with our Settings 22 Channels 501-505 Channels 530 -540 Sky Movies Boost FAQ’s 24 Troubleshooting 25 To add instantly go to the channel and press OK talktalk.co.uk/tvboost Quick connection 27 *You’ll need to have a minimum broadband speed of 5Mb to add TV Boosts. All information and prices in this guide are correct at time of going to print and subject to change. Get the most from your YouView box Enjoy all this: Main Features Access all your favourite Freeview channels Use your TalkTalk PIN to watch more -WTVTfV[#gcYeb`f[X You’ll need a working TV aerial to get your Freeview Sign up to our great value Boosts for a month at a YouView Guide channels. Your YouView box will automatically tune time – perfect for the school holidays or the sports -bYf[X`b fcbcg_Te^ in to the standard channels including some in HD.