The Baroque Tragedy of the Roman Jesuits: Flavia and Beyond*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

The Lives of the Saints

Itl 1 i ill 11 11 i 11 i I 'M^iii' I III! II lr|i^ P !| ilP i'l ill ,;''ljjJ!j|i|i !iF^"'""'""'!!!|| i! illlll!lii!liiy^ iiiiiiiiiiHi '^'''liiiiiiiiilii ;ili! liliiillliili ii- :^ I mmm(i. MwMwk: llliil! ""'''"'"'''^'iiiiHiiiiiliiiiiiiiiiiiii !lj!il!|iilil!i|!i!ll]!; 111 !|!|i!l';;ii! ii!iiiiiiiiiiilllj|||i|jljjjijl I ili!i||liliii!i!il;.ii: i'll III ''''''llllllllilll III "'""llllllll!!lll!lllii!i I i i ,,„, ill 111 ! !!ii! : III iiii CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY l,wj Cornell Unrversity Library BR 1710.B25 1898 V.5 Lives ot the saints. Ili'lll I 3' 1924 026 082 572 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082572 THE ilibes? of tlje t)atnt0 REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE FIFTH THE ILities of tlje g)amt6 BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE FIFTH LONDON JOHN C. NFMMO &-• NEW YORK . LONGMANS, GREEN. CO. MDCCCXCVIll / , >1< ^-Hi-^^'^ -^ / :S'^6 <d -^ ^' Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> CO. At the Ballantyne Press *- -»5< im CONTENTS PAGE Bernardine . 309 SS. Achilles and comp. 158 Boniface of Tarsus . 191 B. Alcuin 263 Boniface IV., Pope . 345 S. Aldhelm .... 346 Brendan of Clonfert 217 „ Alexander I., Pope . -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Historiography Early Church History

HISTORIOGRAPHY AND EARLY CHURCH HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS Historiography Or Preliminary Issues......................................................... 4 Texts ..................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. 5 Definition.............................................................................................................. 5 Necessity............................................................................................................... 5 What Is Church History?............................................................................. 6 What Is The Biblical Philosophy Of History? ............................................ 7 The Doctrine Of God............................................................................................ 7 The Doctrine Of Creation..................................................................................... 8 The Doctrine Of Predestination............................................................................ 8 Why Study Church History? ....................................................................... 9 The Faithfulness Of God .................................................................................... 10 Truth And Experience ........................................................................................ 10 Truth And Tradition .......................................................................................... -

The Alleged Persecution of the Roman Christians by the Emperor Domitian

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2005 The alleged persecution of the Roman Christians by the emperor Domitian Ken Laffer Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Laffer, K. (2005). The alleged persecution of the Roman Christians by the emperor Domitian. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/639 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/639 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

The Roman Martyrology

The Roman Martyrology By the Catholic Church Originally published 10/2018; Current version 5/2021 Mary’s Little Remnant 302 East Joffre St. Truth or Consequences, NM 87901-2878 Website: www.JohnTheBaptist.us (Send for a free catalog) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Sixteenth Day of the Second Month ............. 23 LITURGICAL DIRECTIONS AND NOTES ......................... 7 The Seventeenth Day of the Second Month ........ 23 FIRST MONTH ............................................................ 9 The Eighteenth Day of the Second Month .......... 24 The Nineteenth Day of the Second Month ......... 24 The First Day of the First Month ........................... 9 The Twentieth Day of the Second Month ........... 24 The Second Day of the First Month ...................... 9 The Twenty-First Day of the Second Month ....... 24 The Third Day of the First Month ......................... 9 The Twenty-Second Day of the Second Month ... 25 The Fourth Day of the First Month..................... 10 The Twenty-Third Day of the Second Month ...... 25 The Fifth Day of the First Month ........................ 10 The Twenty-Fourth Day of the Second Month ... 25 The Sixth Day of the First Month ....................... 10 The Twenty-Fifth Day of the Second Month ....... 26 The Seventh Day of the First Month .................. 10 The Twenty-Sixth Day of the Second Month ...... 26 The Eighth Day of the First Month ..................... 10 The Twenty-Seventh Day of the Second Month . 26 The Ninth Day of the First Month ...................... 11 The Twenty-Eighth Day of the Second Month .... 27 The Tenth Day of the First Month ...................... 11 The Eleventh Day of the First Month ................. 11 THIRD MONTH ......................................................... 29 The Twelfth Day of the First Month .................. -

Philostratus's Apollonius

PHILOSTRATUS’S APOLLONIUS: A CASE STUDY IN APOLOGETICS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE Andrew Mark Hagstrom A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Zlatko Pleše Bart Ehrman James Rives © 2016 Andrew Mark Hagstrom ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Andrew Mark Hagstrom: Philostratus’s Apollonius: A Case Study in Apologetics in the Roman Empire Under the direction of Zlatko Pleše My argument is that Philostratus drew on the Christian gospels and acts to construct a narrative in which Apollonius both resembled and transcended Jesus and the Apostles. In the first chapter, I review earlier scholarship on this question from the time of Eusebius of Caesarea to the present. In the second chapter, I explore the context in which Philostratus wrote the VA, focusing on the Severan dynasty, the Second Sophistic, and the struggle for cultural supremacy between Pagans and Christians. In the third chapter, I turn to the text of the VA and the Christian gospels and acts. I point out specific literary parallels, maintaining that some cannot be explained by shared genre. I also suggest that the association of the Egyptian god Proteus with both Philostratus’s Apollonius and Jesus/Christians is further evidence for regarding VA as a polemical response to the Christians. In my concluding chapter, I tie the several strands of my argument together to show how they collectively support my thesis. -

FLAVIA DOMITILLA AS DELICATA: a NEW INTERPRETATION of SUETONIUS, VESP. 3* in This Way Suetonius Informs Us About Flavia Domitill

FLAVIA DOMITILLA AS DELICATA: A NEW INTERPRETATION OF SUETONIUS, VESP. 3* Abstract: This paper proposes a new interpretation of the passage in Suetonius’ Life of Vespasian (Suet., Vesp. 3). The ancient historian, talking about Flavia Domitilla, the wife of Vespasian and the mother of Titus and Domitian, defines her as delicata of Statilius Capella, the Roman knight from Sabratha. Until now, scholars have thought that the relationship between Flavia Domitilla and Statilius Capella was sexual in nature, on the basis of the literary sources concerning the adjective delicatus/a and its meaning. Thanks to the epigraphic evidence about the delicati, not yet analyzed in reference to this pas- sage, it is possible to reach to new conclusions about Flavia Domitil- la’s status. The paper reviews her relationship with Statilius Capella, the sentence of the recuperatores who declared her ingenua and consequently Roman citizen (and not vice versa), and the role played in this trial by Flavius Liberalis. Inter haec Flaviam Domitillam duxit uxorem, Statili Capellae equitis R(omani) Sabratensis ex Africa delicatam olim Latinaeque condi- cionis, sed mox ingenuam et civem Rom(anam) reciperatorio iudicio pronuntiatam, patre asserente Flavio Liberale Ferenti genito nec quic- quam amplius quam quaestorio scriba. Ex hac liberos tulit Titum et Domitianum et Domitillam. Uxori ac filiae superstes fuit atque utramque adhuc privatus1. In this way Suetonius informs us about Flavia Domitilla2, the wife of Vespasian and the mother of Titus and Domitian. This evidence of Suetonius is of particular importance because it constitutes the only information about her. In fact, apart from the Epitome de Caesaribus, where we find a brief reference to Flavia Domitilla, Suetonius represents the only known source about her life. -

CLEMENT of ROME and DOMITIAN's EMPIRE 7He .Fo!

CHAPTER FOUR CLEMENT OF ROME AND DOMITIAN'S EMPIRE 7he .fo!filment qf the imperial peace in Clement's community Clement's Corinthians has been convincingly dated as contemporary with Domitian's reign (A.D. 81-96), and more specifically between A.D. 94 and 97 during which the "sudden and repeated misfortunes (ta~ ai<pvt3iou~ mt E7taA.AfJA.ou~ y£vO!lEVa~ lJ!ltV ow<popa~) and calami ties (Kat 7t€pt7ttroon~)" occurred that had delayed the sending of the letter (Cor. l, 1). 1 Christian writers from Hegesippus and Melito of Sardis onwards claimed that Domitian persecuted Christianity, so that it would be reasonable to conclude that Clement's words here refer to that reign and such a persecution. 2 Furthermore, as Irenaeus (Adv. Haer. V, 30,3) connects the Apocalypse with the reign of Domitian, it would follow that this work is a reaction to that persecution. As that persecution can also be seen as part of the plan of Domitian, as the new Augustus, to reconstruct the Imperial Cult, the developing theology of these two chronologically contemporary works can be related to the developing theology of the Imperial Cult. Since however it has been denied that Domitian persecuted Chris tianity and particularly influenced the Imperial Cult itself, we will begin by discussing the question of Domitian's persecution (section A) as a background to an analysis of the contra-cultural ideology of Order as it appears in Clement's Corinthians (section B). We shall reserve for Chapter 5 our further discussion of Domitian's reform of the cult and the reflection of that reform in the Apocalypse. -

Egypt Under Roman Rule: the Legacy of Ancient Egypt I ROBERT K

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF EGYPT VOLUME I Islamic Egypt, 640- I 5 I 7 EDITED BY CARL F. PETRY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE CONTENTS The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2Ru, United Kingdom http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY roorr-42rr, USA http://www.cup.org ro Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3 r66, Australia © Cambridge University Press r998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published r998 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge List of illustrations to chapter I 3 ix List of contributors x Typeset in Sabon 9.5/r2 pt [CE] Preface xm A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Note on transliteration xv Maps xvi ISBN o 5 2r 4 7r 3 7 o hardback r Egypt under Roman rule: the legacy of Ancient Egypt I ROBERT K. RITNER 2 Egypt on the eve of the Muslim conquest 34 WALTER E. KAEGI 3 Egypt as a province in the Islamic caliphate, 641-868 62 HUGH KENNEDY 4 Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Tuliin to Kafiir, 868-969 86 THIERRY BIANQUIS 5 The Isma'ili Da'wa and the Fatimid caliphate I20 PAUL E. WALKER 6 The Fatimid state, 969-rr7r IJ I PAULA A. -

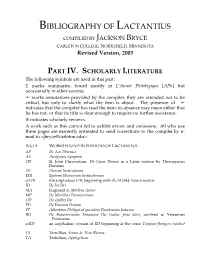

BIBLIOGRAPHY of LACTANTIUS COMPILED by JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LACTANTIUS COMPILED BY JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003 PART IV. SCHOLARLY LITERATURE The following symbols are used in this part: ∑ marks summaries, found mostly in L’Année Philologique [APh] but occasionally in other sources. + marks annotations provided by the compiler; they are intended not to be critical, but only to clarify what the item is about. The presence of + indicates that the compiler has read the item; its absence may mean either that he has not, or that its title is clear enough to require no further assistance. ® indicates scholarly reviews. A work such as this cannot fail to exhibit errors and omissions. All who use these pages are earnestly entreated to send corrections to the compiler by e- mail to <[email protected]>. SIGLA WORKS FOUND IN EDITIONS OF LACTANTIUS AP De Ave Phoenice AS Aenigmata Symposii CD St. John Chrysostom, De Cœna Domini in a Latin version by Hieronymus Donatus DI Divinae Institutiones EDI Epitome Divinarum Institutionum acEDI the acephalous EDI, beginning with ch. 51 [56], Nam si iustitia ID De Ira Dei MA fragment de Motibus Animi MP De Mortibus Persecutorum OD De Opifico Dei PD De Passione Domini PT Adhortatio Philippi ad quendam Theodosium Iudæum RD De Resurrectionis Dominicæ Die (Salve, festa dies), ascribed to Venantius Fotunatus acRD an acephalous version of RD beginning at the verse Tempora florigero rutilant … TS Tertullian, Sermo de Vita Æterna TA Tertullian, Apologeticus J. BRYCE, Bibliography of Lactantius, revised 2003 Part IV. Scholarly Literature 2 VM Lorenzo Valla, De Mystero Eucharistiæ The following subtitles for the seven books of DI are often found: I. -

The Early' Christian Attitude to War

THE EARLY' CHRISTIAN ATTITUDE TO WAR A CONTRIBUTIONTO THE HISTORY OF CHRISTIANETHICS BY C.:"JOHN CADOUX M.A.. D.D. (Londd! M.A. (Oxon) WITH A FOREWORD BY THE Rev. W. E. ORCHARD, D.D. LONDON I HEADLEY BROS. PUBLISHERS, LTD,. 72 OXFORD STREET. W.4 1. 1919 137964 TO MY WIFE 0 glorious Will of God, unfold The splendour of Thy Way, And all shall love as they behold And loving shall obey, Consumed each meaner care and claim In the new passion’s holy flame. 0 speed the hours when o’er the world The vision’s fire shall run ; Night from his ancient throne is burled, Uprisen is Christ the Sun; Through human wills by Thee controlled, Spreads o’er the earth the Age of Gold. REV. G. DARLASTON. FOREWORD THISis a bookwhich stands inneed of no introduc- tion ; it will make its own way by the demand for such a work, and by the exact and patient scholarship with which that demand hashere been met. For we have no workin this country whicheffectively covers this subject ; Harnack's Militiu Chrish' has not been trans- lated, but it will probably be found 'that the present work fills its place. But it is not only the need for this work (of which scholars will be aware),but the serious importance of the subject, which will make the book welcome. Argument for and against the Christian sanction of war has had to be conducted in the past few years in an atmosphere in which the truth has had small chance of emerging.