Cambridge Full

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidental Displacement of Mandibular Third Molar Root Into the Submandibular Space: a Case Report

Case Report ERA’S JOURNAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH VOL.6 NO.1 ACCIDENTAL DISPLACEMENT OF MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR ROOT INTO THE SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE: A CASE REPORT Mayur Vilas Limbhore, Viren S Patil, Shandilya Ramanojam, Vrushika Mahajan, Pallavi Rathi, Kisna Tadas Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College, Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 Received on : 01-04-2018 Accpected on : 10-04-2018 ABSTRACT Address for correspondence Accidental displacement of an impacted third molar, either a crown, Dr. Mayur Vilas Limbhore root piece, or the entire tooth, is a rare complication that occurs Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during surgical removal. The most common sites of dislodgment of an impacted mandibular third molar root are the submandibular, Bharati Vidyapeth Dental College, sublingual and pterygomandibular spaces. Removal of a displaced Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 root from these spaces may be complex due to poor visualization Email: [email protected] and limited access. A thorough evaluation of all significant risk Contact no: +91-8552887325 factors must be performed in advance to prevent complications. This case report reveals the management of accidental displaced mandibular third molar root into the submandibular space. An 39 years-old male patient underwent a third mandibular molar extraction. Accidentally, the mandibular right third molar distal root was displaced into the submandibular space, making necessary a second surgical step. After 2 days awaiting an asymptomatic health status, the second surgical step was successfully performed using multislice CBCT as preoperative imaging guide. The present case report highlights the clinical usefulness of CBCT in proper treatment of the patient. -

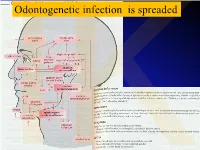

Anatomical Overview

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table

Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 1 Wilson C. Foreign bodies left in the Case series of foreign bodies left in the abdomen. Cases VC Literature n/a n/a n/a n/a Retained abdomen after laparotomy. Trans Am found through publication, interviews, and the author's own Review, Clinician sponges Gynecol Soc. 1884;9:94-117. experience. Experience, and Case Report 2 The Joint Commission. Preventing The Joint Commission recommends that facilities develop IVB Consensus n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a unintended retained foreign objects. effective processes and procedures for preventing Sentinel Event Alert. October 17, unintended retained foreign objects. Their recommendations 2013;51. include a standardized and highly reliable counting system; http://www.jointcommission.org/sea_i development of policies and procedures; practices for ssue_51/. Accessed November 10, counting, wound opening, and closing procedures; 2015. performance of intraoperative radiographs; use of effective communication to include briefings and debriefings; documentation of counts; and assistive technologies (ie, RF tags, RFID, radiopaque, bar coding). Also, the hospital should define a process for conducting RCA for sentinel events, such as URFO. Page 1 of 60 Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 3 Moffatt-Bruce SD, Cook CH, Steinberg 7 elevated risk factors for RSI in pooled data in case-control IIIA Systematic USA hospitals, n/a n/a 3 studies: Estimated SM, Stawicki SP. -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. The space contains mostly loose areolar tissue. -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

A Dictionary of Neurological Signs

FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page i A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iii A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION A.J. LARNER MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Consultant Neurologist Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool Honorary Lecturer in Neuroscience, University of Liverpool Society of Apothecaries’ Honorary Lecturer in the History of Medicine, University of Liverpool Liverpool, U.K. FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iv A.J. Larner, MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery Liverpool, UK Library of Congress Control Number: 2005927413 ISBN-10: 0-387-26214-8 ISBN-13: 978-0387-26214-7 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2006, 2001 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dis- similar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to propri- etary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omis- sions that may be made. -

Treatment for Acute Pain: an Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33

Technical Brief Number 33 R Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Technical Brief Number 33 Treatment for Acute Pain: An Evidence Map Prepared for: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 www.ahrq.gov Contract No. 290-2015-0000-81 Prepared by: Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center Minneapolis, MN Investigators: Michelle Brasure, Ph.D., M.S.P.H., M.L.I.S. Victoria A. Nelson, M.Sc. Shellina Scheiner, PharmD, B.C.G.P. Mary L. Forte, Ph.D., D.C. Mary Butler, Ph.D., M.B.A. Sanket Nagarkar, D.D.S., M.P.H. Jayati Saha, Ph.D. Timothy J. Wilt, M.D., M.P.H. AHRQ Publication No. 19(20)-EHC022-EF October 2019 Key Messages Purpose of review The purpose of this evidence map is to provide a high-level overview of the current guidelines and systematic reviews on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for acute pain. We map the evidence for several acute pain conditions including postoperative pain, dental pain, neck pain, back pain, renal colic, acute migraine, and sickle cell crisis. Improved understanding of the interventions studied for each of these acute pain conditions will provide insight on which topics are ready for comprehensive comparative effectiveness review. Key messages • Few systematic reviews provide a comprehensive rigorous assessment of all potential interventions, including nondrug interventions, to treat pain attributable to each acute pain condition. Acute pain conditions that may need a comprehensive systematic review or overview of systematic reviews include postoperative postdischarge pain, acute back pain, acute neck pain, renal colic, and acute migraine. -

Aetio-Pathogenesis and Clinical Pattern of Orofacial Infections

2 Aetio-Pathogenesis and Clinical Pattern of Orofacial Infections Babatunde O. Akinbami Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Rivers State, Nigeria 1. Introduction Microbial induced inflammatory disease in the orofacial/head and neck region which commonly arise from odontogenic tissues, should be handled with every sense of urgency, otherwise within a short period of time, they will result in acute emergency situations.1,2 The outcome of the management of the conditions are greatly affected by the duration of the disease and extent of spread before presentation in the hospital, severity(virulence of causative organisms) of these infections as well as the presence and control of local and systemic diseases. Odontogenic tissues include 1. Hard tooth tissue 2. Periodontium 2. Predisposing factors of orofacial infections Local factors and systemic conditions that are associated with orofacial infections are listed below. Local factors Systemic factors 1. Caries, impaction, pericoronitis Human immunodeficiency virus 2. Poor oral hygiene, periodontitis Alcoholism 3. Trauma Measles, chronic malaria, tuberculosis Diabetis mellitus, hypo- and 4. Foreign body, calculi hyperthyroidism 5. Local fungal and viral infections Liver disease, renal failure, heart failure 6. Post extraction/surgery Blood dyscrasias 7. Irradiation Steroid therapy 8. Failed root canal therapy Cytotoxic drugs 9. Needle injections Excessive antibiotics, 10. Secondary infection of tumors, cyst, Malnutrition fractures 11. -

Complications Following Surgery of Impacted Teeth and Their Management

Chapter 1 Complications Following Surgery of Impacted Teeth and Their Management Çetin Kasapoğlu, Amila Brkić, Banu Gürkan-Köseoğlu and Hülya Koçak-Berberoğlu Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/53400 1. Introduction One of the most performed procedures in the specialty of oral and maxillofacial surgery is removal of impacted teeth, especially third molars. Impaction is defined as failure of teeth to erupt into the dental arch within the expected time [1,2]. The reasons for tooth impaction include several factors subdivided into a local and general factors such as position and size of adjacent teeth, dense overlying bone, excessive soft tissue or a genetic abnormality including abnormal eruption path, dental arch length and space in which to erupt [1-3]. Clinically and radiographically, there are two types of impactions namely complete and partial. Complete impaction means that the tooth is covered by bone and mucosa and is prevented from erupting into a normal functional position; partial impaction means that the tooth is partially visible or in communication with oral cavity, but it has failed to erupt fully into a normal position [1]. The most common impacted teeeth are mandibular and maxillary third molars, followed by the maxillary canines and mandibular premolars. New data suggests that 72,2% of the world population has at least one impacted tooth (usually lower third molar) [3,4]. From the last 40 years, the incidence of impacted teeth has grown through different populations, due to living habits such as soft food diet and lower intensity of the use of the masticatory apparatus [3]. -

Local Anesthesia Manual Local Anesthesia

Local Anesthesia Manual Local Anesthesia Loma Linda University School of Dentistry 2011/2012 Barry Krall DDS 1 Local Anesthesia Manual Local Anesthesia Table of C ontents 4 Course Objectives 5 History of Anesthesia and Sedation 6 Armamentarium 9 Fundamentals of injection technique 12 Pharmacology of local anesthetics 22 Pharmacology of vasoconstrictors 25 Patient evaluation 32 Dosages 36 Complications of local anesthetic injections 42 Supraperiosteal injection 44 IA, lingual and buccal nerve blocks 51 Infratemporal fossa 53 Posterior superior alveolar nerve block 57 Pterygopalatine fossa 58 Greater palatine and nasopalatine nerve blocks 61 Mental/Incisive nerve blocks 64 ASA “field block” injection 66 Supplemental injections 68 Miscellaneous injections 77 Bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis regimen 78 Table of blocks 79 Dosage guidelines 81 References 3 LOCAL ANESTHESIA MANUAL COURSE OBJECTIVES To learn how to administer local anesthetics effectively, safely and painlessly. To do this you need to know how and be able to do 5 things: 1. What you’re giving? Therefore we will discuss the pharmacology of local anesthetics. 2. Who you’re giving it to? We will discuss how to evaluate patients physically and emotionally. This will involve some physiology. Emergency prevention is emphasized. 3. Where to place it? The anatomy of respective nerves and adjacent structures must be learned. 4. How to place it there? Painlessly, in the right amount at the proper rate (slowly). The technique is both an art and a science. 5. How to handle emergencies? Some may occur in your office or elsewhere. As health professionals we should know what to do, especially if we precipitated the event! 4 HISTORY & DEVELOPMENT OF ANESTHESIA & SEDATION Local Anesthesia BEGINNINGS 1. -

Complex Odontogenic Infections

Complex Odontogenic Infections Larry ). Peterson CHAPTEROUTLINE FASCIAL SPACE INFECTIONS Maxillary Spaces MANDIBULAR SPACES Secondary Fascial Spaces Cervical Fascial Spaces Management of Fascial Space Infections dontogenic infections are usually mild and easily and causes infection in the adjacent tissue. Whether or treated by antibiotic administration and local sur- not this becomes a vestibular or fascial space abscess is 0 gical treatment. Abscess formation in the bucco- determined primarily by the relationship of the muscle lingual vestibule is managed by simple intraoral incision attachment to the point at which the infection perfo- and drainage (I&D) procedures, occasionally including rates. Most odontogenic infections penetrate the bone dental extraction. (The principles of management of rou- in such a way that they become vestibular abscesses. tine odontogenic infections are discussed in Chapter 15.) On occasion they erode into fascial spaces directly, Some odontogenic infections are very serious and require which causes a fascial space infection (Fig. 16-1). Fascial management by clinicians who have extensive training spaces are fascia-lined areas that can be eroded or dis- and experience. Even after the advent of antibiotics and tended by purulent exudate. These areas are potential improved dental health, serious odontogenic infections spaces that do not exist in healthy people but become still sometimes result in death. These deaths occur when filled during infections. Some contain named neurovas- the infection reaches areas distant from the alveolar cular structures and are known as coinpnrtments; others, process. The purpose of this chapter is to present which are filled with loose areolar connective tissue, are overviews of fascial space infections of the head and neck known as clefts.