Management of Iatrogenic Dislodgment of a Mandibular Third Molar Into the Pterygomandibular Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidental Displacement of Mandibular Third Molar Root Into the Submandibular Space: a Case Report

Case Report ERA’S JOURNAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH VOL.6 NO.1 ACCIDENTAL DISPLACEMENT OF MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR ROOT INTO THE SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE: A CASE REPORT Mayur Vilas Limbhore, Viren S Patil, Shandilya Ramanojam, Vrushika Mahajan, Pallavi Rathi, Kisna Tadas Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College, Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 Received on : 01-04-2018 Accpected on : 10-04-2018 ABSTRACT Address for correspondence Accidental displacement of an impacted third molar, either a crown, Dr. Mayur Vilas Limbhore root piece, or the entire tooth, is a rare complication that occurs Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during surgical removal. The most common sites of dislodgment of an impacted mandibular third molar root are the submandibular, Bharati Vidyapeth Dental College, sublingual and pterygomandibular spaces. Removal of a displaced Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 root from these spaces may be complex due to poor visualization Email: [email protected] and limited access. A thorough evaluation of all significant risk Contact no: +91-8552887325 factors must be performed in advance to prevent complications. This case report reveals the management of accidental displaced mandibular third molar root into the submandibular space. An 39 years-old male patient underwent a third mandibular molar extraction. Accidentally, the mandibular right third molar distal root was displaced into the submandibular space, making necessary a second surgical step. After 2 days awaiting an asymptomatic health status, the second surgical step was successfully performed using multislice CBCT as preoperative imaging guide. The present case report highlights the clinical usefulness of CBCT in proper treatment of the patient. -

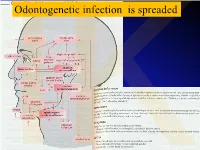

Anatomical Overview

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table

Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 1 Wilson C. Foreign bodies left in the Case series of foreign bodies left in the abdomen. Cases VC Literature n/a n/a n/a n/a Retained abdomen after laparotomy. Trans Am found through publication, interviews, and the author's own Review, Clinician sponges Gynecol Soc. 1884;9:94-117. experience. Experience, and Case Report 2 The Joint Commission. Preventing The Joint Commission recommends that facilities develop IVB Consensus n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a unintended retained foreign objects. effective processes and procedures for preventing Sentinel Event Alert. October 17, unintended retained foreign objects. Their recommendations 2013;51. include a standardized and highly reliable counting system; http://www.jointcommission.org/sea_i development of policies and procedures; practices for ssue_51/. Accessed November 10, counting, wound opening, and closing procedures; 2015. performance of intraoperative radiographs; use of effective communication to include briefings and debriefings; documentation of counts; and assistive technologies (ie, RF tags, RFID, radiopaque, bar coding). Also, the hospital should define a process for conducting RCA for sentinel events, such as URFO. Page 1 of 60 Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 3 Moffatt-Bruce SD, Cook CH, Steinberg 7 elevated risk factors for RSI in pooled data in case-control IIIA Systematic USA hospitals, n/a n/a 3 studies: Estimated SM, Stawicki SP. -

29360-Oral Cavity Dr. Alexandra Borges.Pdf

ORAL CAVITY: ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGIES Alexandra Borges, MD COI Disclosure Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa I have nothing to disclose Champalimaud Foundation Lisbon, Portugal ECHNNR 2021 ECHNNR 2021 MR ANATOMY LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Become familiar with OC anatomy and the importance of using adequate terminology when reporting OC studies NASOPHARYNX NASAL CAVITY • Learn how to tailor imaging studies • Understand the different patterns of malignant tumor spread according to the different tumor subsites OROPHARYNX ORAL CAVITY HYPOPHARYNX BOUNDARIES CONTENTS: ORAL TONGUE Superior: • hard palate • superior alveolar ridge Inferior: • floor of the mouth • inferior alveolar ridge ITM Laterally: • cheeks and buccal mucosaosa Anterior: • Lips Posterior: • oropharynx ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic tongue muscles EM: Styloglossus tongue retraction and elevation Styloglossus Palatoglossus Hyoglossus SG Geniglossus HG GG CN XII CN X EM: Palatoglossus elevation of the tongue EM: Hyoglossus tongue depression and retraction EM: Genioglossus tongue protrusion ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic muscles GG GH TONGUE INNERVATION ORAL CAVITY IX sensitive and Spatial subdivision taste CN X Motor • Mucosal area • Tongue root • Sublingual space CN XII Motor • Submandibular space Lingual nerve: Sensitive (branch of V3) • Buccomasseteric region Taste (chorda tympani) ORAL MUCOSAL SPACE ROOT OF THE TONGUE 1. Lips 2. Gengiva (sup. alveolar ridge) 3. Gengiva (inf. alveolar ridge) 4. Buccal 5. Palatal 6. Sublingual/FOM 7. Retromolar trigone GG 8. Tongue ROT BOT Vestibule GH Mucosa -

Head & Neck Surgery Course

Head & Neck Surgery Course Parapharyngeal space: surgical anatomy Dr Pierfrancesco PELLICCIA Pr Benjamin LALLEMANT Service ORL et CMF CHU de Nîmes CH de Arles Introduction • Potential deep neck space • Shaped as an inverted pyramid • Base of the pyramid: skull base • Apex of the pyramid: greater cornu of the hyoid bone Introduction • 2 compartments – Prestyloid – Poststyloid Anatomy: boundaries • Superior: small portion of temporal bone • Inferior: junction of the posterior belly of the digastric and the hyoid bone Anatomy: boundaries Anatomy: boundaries • Posterior: deep fascia and paravertebral muscle • Anterior: pterygomandibular raphe and medial pterygoid muscle fascia Anatomy: boundaries • Medial: pharynx (pharyngobasilar fascia, pharyngeal wall, buccopharyngeal fascia) • Lateral: superficial layer of deep fascia • Medial pterygoid muscle fascia • Mandibular ramus • Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland • Posterior belly of digastric muscle • 2 ligaments – Sphenomandibular ligament – Stylomandibular ligament Aponeurosis and ligaments Aponeurosis and ligaments • Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis: separates parapharyngeal spaces to two compartments: – Prestyloid – Poststyloid • Cloison sagittale: separates parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space Aponeurosis and ligaments Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis Muscles stylohyoidien Stylopharyngeal , And styloglossus muscles Prestyloid compartment Contents: – Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland – Minor or ectopic salivary gland – CN V branch to tensor -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. The space contains mostly loose areolar tissue. -

The Oromaxillofacial Rehabilitation in Orthodontic-Surgical Protocols

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2015044 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2016;19:203 © The authors The oromaxillofacial rehabilitation in orthodontic-surgical protocols Th. Gouzland1,2, M. Fournier1 1 Kinesiologist, specializing in oromaxillofacial rehabilitation 2 Educator SUMMARY Oro-maxillo-facial rehabilitation is an ancient practice that has developed over recent years through research and integration with physiotherapists in multidisciplinary teams, as is the case with orthodontic- surgical procedures. At the same time, the progress made in orthognathic and orthodontic surgery over the last 20 years encourages more and more patients to undergo surgery. Preoperative treatment is based on early assessment and preparation for optimal surgical conditions to come up with a functional plan. A short stay in a hospital, focusing on rehabilitation, is recommended. During the postoperative phase, the key objectives are to ensure the muscles and arteries all function perfectly, acceptance of the new face, and the immediate correction of any orofacial dyspraxia that has occurred during myofunc- tional therapy. The various specialists in this multidisciplinary team must constantly be in communication. The importance of postoperative physiotherapy will be illustrated by a study consisting of 35 cases of maxillomandibular osteotomy with orthodontic preparation and monitoring. The purpose of this study is to show occurrence of suboccipital and cervical muscle tensions as well as masticatory muscles. Then we will be able to see the importance of these practices, the impact on recovery, the impact on posture and how best to treat. KEYWORDS Physiotherapy, orthognathic surgery, orthodontic, myofunctional therapy, muscles, posture INTRODUCTION The progress made in the techniques and comfortable recovery. This fits into and the results obtained by coupling the current social view where one’s orthognathic surgery with orthodontics image is given greater importance. -

Computed Tomography of the Buccomasseteric Region: 1

605 Computed Tomography of the Buccomasseteric Region: 1. Anatomy Ira F. Braun 1 The differential diagnosis to consider in a patient presenting with a buccomasseteric James C. Hoffman, Jr. 1 region mass is rather lengthy. Precise preoperative localization of the mass and a determination of its extent and, it is hoped, histology will provide a most useful guide to the head and neck surgeon operating in this anatomically complex region. Part 1 of this article describes the computed tomographic anatomy of this region, while part 2 discusses pathologic changes. The clinical value of computed tomography as an imaging method for this region is emphasized. The differential diagnosis to consider in a patient with a mass in the buccomas seteric region, which may either be developmental, inflammatory, or neoplastic, comprises a rather lengthy list. The anatomic complexity of this region, defined arbitrarily by the soft tissue and bony structures including and surrounding the masseter muscle, excluding the parotid gland, makes the accurate anatomic diagnosis of masses in this region imperative if severe functional and cosmetic defects or even death are to be avoided during treatment. An initial crucial clinical pathoanatomic distinction is to classify the mass as extra- or intraparotid. Batsakis [1] recommends that every mass localized to the cheek region be considered a parotid tumor until proven otherwise. Precise clinical localization, however, is often exceedingly difficult. Obviously, further diagnosis and subsequent therapy is greatly facilitated once this differentiation is made. Computed tomography (CT), with its superior spatial and contrast resolution, has been shown to be an effective imaging method for the evaluation of disorders of the head and neck. -

Dynamic Manoeuvres on MRI in Oral Cancers – a Pictorial Essay Diva Shah HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Published online: 2021-07-19 HEAD AND NECK IMAGING Dynamic manoeuvres on MRI in oral cancers – A pictorial essay Diva Shah HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Correspondence: Dr. Diva Shah, HCG Cancer Centre, Sola Science City Road, Ahmedabad ‑ 380060, Gujarat, India. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to be a useful tool in the evaluation of oral malignancies because of direct visualization of lesions due to high soft tissue contrast and multiplanar capability. However, small oral cavity tumours pose an imaging challenge due to apposed mucosal surfaces of oral cavity, metallic denture artefacts and submucosal fibrosis. The purpose of this pictorial essay is to show the benefits of pre and post contrast MRI sequences using various dynamic manoeuvres that serve as key sequences in the evaluation of various small oral (buccal mucosa and tongue as well as hard/soft palate) lesions for studying their extent as well as their true anatomic relationship. Key words: Dynamic manoeuvres; MRI; oral cavity lesions Introduction oral cavity lesions particularly in patients with sub‑mucosal fibrosis, RMT lesions, post‑operative evaluation and in In the imaging of oral cavity lesions, it is important presence of metallic dental streak artefacts. MRI in these to determine precisely the site of tumour origin, size, circumstances scores over MDCT and is a preferred modality trans‑spatial extension and invasion of deep structures.[1] with excellent soft tissue contrast resolution. Evaluation of small tumours of the oral cavity is always a diagnostic challenge for both the head and neck surgeon MR imaging with various dynamic manoeuvres provides and the head and neck radiologist. -

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Chair Dr. David Hedgecoth Professor Katherine Borst Jones Dr. Scott McCoy Copyrighted by Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. 2018 Abstract The clarinet is a complex instrument that blends wood, metal, and air to create some of the world’s most beautiful sounds. Its most intricate component, however, is the human who is playing it. While the clarinet has 24 tone holes and 17 or 18 keys, the human body has 205 bones, around 700 muscles, and nearly 45 miles of nerves. A seemingly endless number of exercises and etudes are available to improve technique, but almost no one comments on how to best use the body in order to utilize these studies to maximum effect while preventing injury. The purpose of this study is to elucidate the interactions of the clarinet with the body of the person playing it. Emphasis will be placed upon the musculoskeletal system, recognizing that playing the clarinet is an activity that ultimately involves the entire body. Aspects of the skeletal system as they relate to playing the clarinet will be described, beginning with the axial skeleton. The extremities and their musculoskeletal relationships to the clarinet will then be discussed. The muscles responsible for the fine coordinated movements required for successful performance on the clarinet will be described. -

18612-Oropharynx Dr. Teresa Nunes.Pdf

European Course in Head and Neck Neuroradiology Disclosures 1st Cycle – Module 2 25th to 27th March 2021 No conflict of interest regarding this presentation. Oropharynx Anatomy and Pathologies Teresa Nunes Hospital Garcia de Orta, Hospital Beatriz Ângelo Portugal Oropharynx: Anatomy and Pathologies Oropharynx: Anatomy Objectives Nasopharynx • Review the anatomy of the oropharynx (subsites, borders, surrounding spaces) Oropharynx • Become familiar with patterns of spread of oropharyngeal infections and tumors Hypopharynx • Highlight relevant imaging findings for accurate staging and treatment planning of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma Oropharynx: Surrounding Spaces Oropharynx: Borders Anteriorly Oral cavity Superior Soft palate Laterally Parapharyngeal space Anterior Circumvallate papillae Masticator space Anterior tonsillar pillars Posteriorly Retropharyngeal space Posterior Posterior pharyngeal wall Lateral Anterior tonsillar pillars Tonsillar fossa Posterior tonsillar pillars Inferior Vallecula Oropharynx: Borders Oropharynx: Borders Oropharyngeal isthmus Superior Soft palate Anterior Circumvallate papillae Anterior 2/3 vs posterior 1/3 of tongue Anterior tonsillar pillars Palatoglossal arch Inferior Vallecula Anterior tonsillar pillar: most common Pre-epiglottic space Glossopiglottic fold (median) location of oropharyngeal squamous Can not be assessed clinically Pharyngoepiglottic folds (lateral) Invasion requires supraglottic laryngectomy !cell carcinoma ! Oropharynx: Borders Muscles of the Pharyngeal Wall Posterior pharyngeal -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament.