Fascial Infections Derived from Maxillary Odontogenic Origins the Spread Pattern of Maxillary Infection Differed from That of Mandibular Infection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidental Displacement of Mandibular Third Molar Root Into the Submandibular Space: a Case Report

Case Report ERA’S JOURNAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH VOL.6 NO.1 ACCIDENTAL DISPLACEMENT OF MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR ROOT INTO THE SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE: A CASE REPORT Mayur Vilas Limbhore, Viren S Patil, Shandilya Ramanojam, Vrushika Mahajan, Pallavi Rathi, Kisna Tadas Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College, Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 Received on : 01-04-2018 Accpected on : 10-04-2018 ABSTRACT Address for correspondence Accidental displacement of an impacted third molar, either a crown, Dr. Mayur Vilas Limbhore root piece, or the entire tooth, is a rare complication that occurs Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during surgical removal. The most common sites of dislodgment of an impacted mandibular third molar root are the submandibular, Bharati Vidyapeth Dental College, sublingual and pterygomandibular spaces. Removal of a displaced Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 root from these spaces may be complex due to poor visualization Email: [email protected] and limited access. A thorough evaluation of all significant risk Contact no: +91-8552887325 factors must be performed in advance to prevent complications. This case report reveals the management of accidental displaced mandibular third molar root into the submandibular space. An 39 years-old male patient underwent a third mandibular molar extraction. Accidentally, the mandibular right third molar distal root was displaced into the submandibular space, making necessary a second surgical step. After 2 days awaiting an asymptomatic health status, the second surgical step was successfully performed using multislice CBCT as preoperative imaging guide. The present case report highlights the clinical usefulness of CBCT in proper treatment of the patient. -

Anatomical Overview

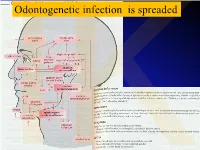

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table

Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 1 Wilson C. Foreign bodies left in the Case series of foreign bodies left in the abdomen. Cases VC Literature n/a n/a n/a n/a Retained abdomen after laparotomy. Trans Am found through publication, interviews, and the author's own Review, Clinician sponges Gynecol Soc. 1884;9:94-117. experience. Experience, and Case Report 2 The Joint Commission. Preventing The Joint Commission recommends that facilities develop IVB Consensus n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a unintended retained foreign objects. effective processes and procedures for preventing Sentinel Event Alert. October 17, unintended retained foreign objects. Their recommendations 2013;51. include a standardized and highly reliable counting system; http://www.jointcommission.org/sea_i development of policies and procedures; practices for ssue_51/. Accessed November 10, counting, wound opening, and closing procedures; 2015. performance of intraoperative radiographs; use of effective communication to include briefings and debriefings; documentation of counts; and assistive technologies (ie, RF tags, RFID, radiopaque, bar coding). Also, the hospital should define a process for conducting RCA for sentinel events, such as URFO. Page 1 of 60 Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 3 Moffatt-Bruce SD, Cook CH, Steinberg 7 elevated risk factors for RSI in pooled data in case-control IIIA Systematic USA hospitals, n/a n/a 3 studies: Estimated SM, Stawicki SP. -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. The space contains mostly loose areolar tissue. -

Rediscovering the Rhetoric of Women's Intellectual

―THE ALPHABET OF SENSE‖: REDISCOVERING THE RHETORIC OF WOMEN‘S INTELLECTUAL LIBERTY by BRANDY SCHILLACE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Christopher Flint Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ________Brandy Lain Schillace___________________________ candidate for the __English PhD_______________degree *. (signed)_____Christopher Flint_______________________ (chair of the committee) ___________Athena Vrettos_________________________ ___________William R. Siebenschuh__________________ ___________Atwood D. Gaines_______________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) ___November 12, 2009________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii Table of Contents Preface ―The Alphabet of Sense‖……………………………………...1 Chapter One Writers and ―Rhetors‖: Female Educationalists in Context…..8 Chapter Two Mechanical Habits and Female Machines: Arguing for the Autonomous Female Self…………………………………….42 Chapter Three ―Reducing the Sexes to a Level‖: Revolutionary Rhetorical Strategies and Proto-Feminist Innovations…………………..71 Chapter Four Intellectual Freedom and the Practice of Restraint: Didactic Fiction versus the Conduct Book ……………………………….…..101 Chapter Five The Inadvertent Scholar: Eliza Haywood‘s Revision -

Studies of the Function of the Human Pylorus : and Its Role in The

+.1 Studúes OlTlæ Ftrnctíon OJTIrc Humanfolonts And,Iß R.ole InTlæ Riegulø;tíon OÍ Cústríß Drnptging David R. Fone Departments of Medicine and Gastroenterology, Royal Adelaide Hospital University of Adelaide August 1990 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS . SUMMARY vil DECLARATION...... X DED|CAT|ON.. .. ... xt ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xil CHAPTER 1 ANATOMY OF THE PYLORUS 1.1 INTRODUCTION.. 1 1.2 MUSCULAR ANATOMY 2 1.3 MUCOSAL ANATOMY 4 1.4 NEURALANATOMY 1.4.1 Extrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 5 1.4.2 lntrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 7 1.5 INTERSTITIAL CELLS OF CAJAL 8 1.6 CONCLUSTON 9 CHAPTER 2 MEASUREMENT OF PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.1 INTRODUCTION 10 2.2 METHODOLOG ICAL CHALLENGES 2.2.1 The Anatomical Mobility of the Pylorus . 10 2.2.2 The Narrowness of the Zone of Pyloric Contraction 12 2.3 METHODS USED TO MEASURE PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.3.1 lntraluminal Techniques 2.3.1.1 Balloon Measurements. 12 t 2.3 1.2 lntraluminal Side-hole Manometry . 13 2.3 1.9 The Sleeve Sensor 14 2.3 1.4 Endoscopy. 16 2.3 1.5 Measurements of Transpyloric Flow . 16 2.3 'I .6 lmpedance Electrodes 16 2.3.2 Extraluminal Techniques For Recording Pyl;'; l'¡"r¡iit¡l 2.3.2.'t Strain Gauges . 17 2.3.2.2 lnduction Coils . 17 2.3.2.3 Electromyography 17 2.3.3 Non-lnvasive Approaches For Recording 2.3.3.1 Radiology :ï:: Y:1":'1 18 2.3.9.2 Ultrasonography . 1B 2.3.3.3 Electrogastrography 19 2.3.4 ln Vitro Studies of Pyloric Muscle 19 2.4 CONCLUSTON. -

Nbde Part 2 Decks and Remembed-Arroz Con Mango

ARROZ CON MANGO Dear friends, these are remembered/repeated questions (RQs) and answers I COPIED and PASTED from different discussions on Facebook. I feel sorry because I couldn’t organize the file the way I wanted but I hope it helps. Probably you’ll find some wrong answers in this file, but PLEASE … DO NOT CRITICIZE! Find out the right answer, learn it, share it, PASS your test and BE HAPPY J I wish you all the best GOD BLESS YOU! PAITO 1. All of the following are adverse effects of opioids except? diarrhea and somnolence 2. Advantage of osteogenesis distraction is? less relapse, large movements 3. An investigation that is not accurate but consistent is: reliability 4. Remineralized enamel is rough and cavitation? Dark hard and opaque 5. Characteristics of a child with autism - repetitive action, sensitive to light and noise 6. S,z,che sounds : Teeth barely touching – True 7. Something about bio-transformation, more polar and less lipid soluble? - True 8. How much of he population has herpes? 80% - (65-90% worldwide; 80-85% USA) More than 3.7 billion people under the age of 50 – or 67% of the population – are infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), according to WHO's first global estimates of HSV-1 infection published today in the journal PLOS ONE. 9. Steps of plaque formation: pellicle, biofilm, materia alba, plaque 10. Dose of hydrocortisone taken per year that will indicate have adrenal insufficiency and need supplement dose for surgery - 20 mg 2 weeks for 2 years 11. Rpd clasp breakage due to what? Work hardening 12. -

Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa

Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa Surgical Anatomy of the Infratemporal Fossa John D.Langdon Professor and Head of Department Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery King’s College London, UK Barry K.B.Berkovitz Reader in Anatomy Division of Anatomy, Cell and Human Biology King’s College London, UK Bernard J.Moxham Professor of Anatomy and Head of Teaching in Biosciences Cardiff School of Biosciences Cardiff University, UK MARTIN DUNITZ © 2003 Martin Dunitz, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group First published in the United Kingdom in 2003 by Martin Dunitz, Taylor & Francis Group plc, 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Tel.: +44 (0) 20 7583 9855 Fax.: +44 (0) 20 7842 2298 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dunitz.co.uk This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P OLP. Although every effort has been made to ensure that all owners of copyright material have been acknowledged in this publication, we would be glad to acknowledge in subsequent reprints or editions any omissions brought to our attention. -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

A Dictionary of Neurological Signs

FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page i A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iii A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION A.J. LARNER MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Consultant Neurologist Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool Honorary Lecturer in Neuroscience, University of Liverpool Society of Apothecaries’ Honorary Lecturer in the History of Medicine, University of Liverpool Liverpool, U.K. FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iv A.J. Larner, MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery Liverpool, UK Library of Congress Control Number: 2005927413 ISBN-10: 0-387-26214-8 ISBN-13: 978-0387-26214-7 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2006, 2001 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dis- similar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to propri- etary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omis- sions that may be made. -

The University of Sheffield Object

The University of Sheffield Object Relations Middle Group and Attachment Theory: Gender Development, Spousal Abuse, and Qualitative Research On Youth Crime s. S. Wier PhD Object Relations Middle Group and Attachment Theory: Gender Development, Spousal Abuse, and Qualitative Research on Youth Crime Stewart Scott Wier PhD Centre for Psychotherapeutic Studies January 2003 Acknowledgments There are a number of people to whom I wish to express my sincere thanks and appreciation for their role in facilitating this achievement. Dr. Don Carveth first introduced me to the subject of psychoanalytic thought. He encouraged me to develop the potential he saw as an undergraduate student, and has continued to do so over the years, the most recent being through his endorsement of this particular dream. Dr. Gottfried Paasche is responsible for acquainting me with the process of qualitative methods of research, around which much of this paper is based, as well as for sponsoring my application to pursue this endeavor. The initial efforts for this project began over a decade ago at the University of Exeter under the direction of Dr. Paul Kline. He provided outstanding support and optimism surrounding these labours, in addition to showing compassion about my eventual decision to suspend them. Several years later, and following the retirement of Dr. Kline, Dr. Robert Young ofthe University of Sheffield, willingly assumed the responsibility ofacting as my subsequent supervisor despite the enormous demands on his time. The chair of the department for Psychotherapeutic Studies, Geraldine Shipton, displayed integrity, moral commitment, and consistency throughout the entire process. Dr. Christopher Cordess and Dr. Corinne Squire provided informed and respectful critical comments through a very cordial session which served to make a potentially distressing experience exceedingly pleasant, and brought considerable improvement to the first effort.