Martinus Noster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concordia Theological Quarterly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 83:3–4 July/October 2019 Table of Contents After Canons, Councils, and Popes: The Implications of Luther’s Leipzig Debate for Lutheran Ecclesiology Richard J. Serina Jr. ...................................................................................... 195 The Leipzig Debate and Theological Method Roland F. Ziegler .......................................................................................... 213 Luther and Liberalism: A Tale of Two Tales (Or, A Lutheran Showdown Worth Having) Korey D. Maas .............................................................................................. 229 Scripture as Philosophy in Origen’s Contra Celsum Adam C. Koontz ........................................................................................... 237 Passion and Persecution in the Gospels Peter J. Scaer .................................................................................................. 251 Reclaiming Moral Reasoning: Wisdom as the Scriptural Conception of Natural Law Gifford A. Grobien ....................................................................................... 267 Anthropology: A Brief Discourse David P. Scaer ............................................................................................... 287 Reclaiming the Easter Vigil and Reclaiming Our Real Story Randy K. Asburry ......................................................................................... 325 Theological Observer ................................................................................................ -

Martin Luther

TRUTHmatters October 2002 Volume II, Issue 4 ous errors of John Wycliffe who said ‘It is not MARTIN LUTHER necessary for salvation to believe that the Ro- (This is the second of two articles) man Church is above all others.’ And you are espousing the pestilent errors of John Hus, We shift now to Luther’s work in the who claimed that Peter neither was nor is the following two to three years. It has already been head of the Holy Catholic Church.” mentioned that he was catapulted into the fore- This was dangerous ground for Luther ground and the next two or three years were to be on because John Hus had been burned as both hard and rewarding to the Augustinian a heretic and if Luther could be forced into this monk. I will only cover two of these most im- stand, he could also be called a heretic. A portant events. The Leipzig Debate in July of lunch break was due and during this break Lu- 1519 and the famous Diet of Worms in 1521. ther went to the library and quickly looked up The Leipzig debate was held in the large what Hus had believed and found that it was hall of the Castle of Pleissenberg at Leipzig. The exactly what he believed. In the afternoon ses- debate was between Johann Eck who repre- sion, Luther astonished the whole assembly by sented the Roman church and Dr. Carlstadt and declaring in effect: “Ja, Ich bin ein Hussite” or Dr. Martin Luther. It was a great intellectual “Yes, I am a Hussite.” It is from this debate battle that lasted three weeks. -

564158Eb19f006.65831545.Pdf

HEARTH AND HOME Left: Later Protestants liked to describe the Luthers as the ideal parsonage family. Here a 19th-c. artist imagines the family gathered around to sing with friend Melancthon in the background. DIABOLICAL BAGPIPES Below: Luther’s opponents caricatured him as merely a mouthpiece for the devil. Protestants countered that monks, not Luther, were the devil’s instruments. RSITY E Did you know? NIV U LUTHER LOVED TO PLAY THE LUTE, ONCE WENT ON STRIKE FROM HIS CONGREGATION, AND OGY, EMORY HATED TO COLLECT THE RENT ES F THEOL O VA L MAG I NE MAN MICHELANGELO, MUSIC, AND MASS E • Christopher Columbus set sail when Luther was a LER SCHOO schoolboy, and Michelangelo was completing his Sis- tine Chapel ceiling when Luther began teaching theol- REFORMATION, GE E RMANY / BRIDG RARY, CAND B TH ogy as a young man. SINGING CONGREGANTS, STRIKING PASTOR F • Luther preferred music to any other school subject, Luther made singing a central part of Protestant wor- OGY LI UM O OTHA, GE E G and he became very skilled at playing the lute. Upon ship. In his German Mass (1526), he dispensed with the US IN, THEOL E becoming a monk at age 21, he had to give the lute away. choir and assigned all singing to the congregation. He L M NST • When Luther celebrated his first Mass as a priest in often called congregational rehearsals during the week EDE RNATIONA 1507, he trembled so much he nearly dropped the bread so people could learn new hymns. TION, PITTS E NT OSS FRI and cup. -

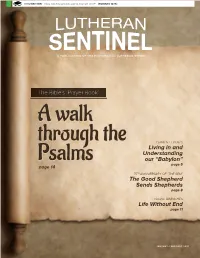

The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds Life Without End the Bible's

IT IS WRITTEN: “How can they preach, unless they are sent?” (ROMANS 10:15) A PUBLICATION OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD The Bible’s ‘Prayer Book’ A walk through the CURRENT EVENTS Living in and Understanding our “Babylon” Psalms page 5 page 14 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF “THE SEM” The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds page 8 YOUNG BRANCHES Life Without End page 11 JANUARY– FEBRUARY 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT: by REV. JOHN A. MOLDSTAD, President EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD, Mankato, Minn. HowVaporVapor Makes Plans Dear Members and Friends of our ELS: We know what happens when a glass of hot water is placed his ventures, and now he was doing even more expansion. outside on an icy morning. For a time, vapor rises when the When I interjected, “I guess the Lord has really blessed you,” heat meets the cold. Then it quickly disappears. That rising I could sense he felt momentarily uneasy. He did not speak vapor is used by the writer of James to have us reflect on at all of his accomplishments as gifts from God. He replied, the way we go about our lives in making plans. Planning for “Well, I don’t mean to be ‘brag-tocious’ but…” Then he quickly the new year – a year we pray will not repeat the pandemic launched into more of his lucrative plans. challenges of 2020 – needs always to consider what James wrote by inspiration of God the Holy Spirit: Now listen, you Could we also be guilty of the sin of boasting in a less obvious who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, way? Our sinful mind that we carry with us daily as unwanted spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” baggage tempts us to leave God out of the picture. -

Alexandra Harris

Harris 1 The 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation A Turning Point in World History Alexandra Harris “Who had the more convincing argument at the Leipzig Debate: John Eck or Martin Luther? During the time of the Protestant Reformation, an important event known as the Leipzig Debate occurred. This was primarily between two men with varying views on religion, Dr. Johann Eck and Martin Luther. The latter of these men was a German monk who was the father of Lutheranism, a branch of Christianity that emerged during the Protestant Reformation. John Eck was a German theologian who was friendly with Luther until 1517, which was when Luther published his Ninety-five Theses. Eck deemed these theses to be unorthodox and challenged Luther and one of his disciples to a debate on their differing views of religious doctrine. The Leipzig Debate took place in Germany in the year 1519, in the great hall of the castle named Pleissenburg, which is in Leipzig. A year before this, in 1518, this public debate was initiated by Johann Eck, who challenged both Andreas Rudolf Bodenstein von Karlstadt and Martin Luther to a debate on Luther's teachings. The discussion between Eck and Luther took place on the dates of July 4 - July 13, during which Luther emphasized his belief of faith in God alone; this stance can be backed up by scripture. John Eck defended Catholic doctrine and walked away the winner of the debate, according to the theologians of the University of Leipzig. Despite the ruling of the University of Leipzig, Martin Luther had the more convincing argument at the Leipzig Debate because he had superior knowledge of background information, he defended doctrine that remains true to the teachings of the Holy Bible, and he won over many new followers. -

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION at 500 YEARS from RUPTURE to DIALOGUE Jaume Botey

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AT 500 YEARS FROM RUPTURE TO DIALOGUE Jaume Botey 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 2. Luther’s personality and the theme of justification ...................... 7 3. The great controversies, and the progressive development of his thought ................................................................. 10 4. The great treatises of 1520 and the diet of worms .......................... 16 5. The peasants’ war .................................................................................... 21 6. Consolidation of the reformation ....................................................... 24 7. Epilogue .................................................................................................... 28 Notes ............................................................................................................. 31 Bibliography ................................................................................................. 32 In memory… In February, while we were preparing the English edition of this booklet, its author, Jaume Botey Vallés, passed away. As a member of the Cristianisme i Justícia team, Jaume was a person profoundly committed to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, and he worked energetically for peace and for the other world that is possible. Jaume, we will miss you greatly. Cristianisme i Justícia Jaume Botey has a licentiate in philosophy and theology and a doctorate in anthropology. He has been a professor of -

The Leipzig Debate Who Won? John Eck Or Martin Luther

The Leipzig Debate Who Won? John Eck or Martin Luther Curriculum Area: World History/European History Level: AP/Honors Author: Hank Bitten Lesson Objectives: New Jersey Core Content Standards: 6.2.12.B.2.b: Relate the division of European regions during this time period into those that remained Catholic and those that became Protestant to the practice of religion in the New World. 6.2.12.D.2.b: Determine the factors that led to the Reformation and the impact on European politics. NY Global Studies Learning Standards: G2: 2. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses: the challenge to the power and authority of the Roman Catholic Church Common Core Standards: (Grades 9-10) Reading in History 9-10:1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of information. Reading in History 9-10:2 Determine the central ideas of information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text. Reading in History 9-10:8 Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claims. Common Core Standards: (Grades 11-12) Reading in History 11-12:1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole. Reading in History 11-12:2 Determine the central ideas of information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationship among key details and ideas. -

October-2003.Pdf

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 29 October 2003 Number 4 CONTENTS EDITORIALS Editor’s Note ........................................................................ 354 A Faculty Statement ............................................................. 356 Theological Potpourri ........................................................... 358 Theological Observers ............................................................ 363 ARTICLES The Beginnings of the Papacy in the Early Church Quentin F. Wesselschmidt ........................................................ 374 Antichrist?: The Lutheran Confessions on the Papacy Charles P. Arand .................................................................. 392 The Papacy in Perspective: Luther’s Reform and Rome Robert Rosin ........................................................................ 407 Vatican II’s Conception of the Papacy: A Lutheran Response Richard H. Warneck ............................................................. 427 Ut Unum Sint and What It Says about the Papacy: Description and Response Samuel H. Nafzger ............................................................... 447 Papacy as a Constitutive Element of Koinonia in Ut Unum Sint? Edward J. Callahan ............................................................... 463 HOMILETICAL HELPS .................................................................. 483 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 506 BOOKS RECEIVED .......................................................................... -

MARTIN LUTHER and the GERMAN REFORMATION I. Mansfeld

MARTIN LUTHER AND THE GERMAN REFORMATION LUTHER’S EARLY YEARS I. Mansfeld, Mining and the Luder family (1483-1501) A. Middle class lifestyle; Hans and Margaret Luder B. Influence of Mansfeld years: toughness, importance of creating networks, how to be a leader, respect for class distinctions II. The Scholar and the Monk (1501-1511) A. 1501 entered the University of Erfurt; via moderna curriculum; Humanism; completed B.A, M.A; headed for law school B. July 1505 frightened by thunderstorm and vows to become a monk. Enters Augustinian monastery; continues scholarly studies; Johann von Staupitz becomes his mentor C. Battles religious despair and depression; comes to insist on the primacy of scripture as source of all authority. III. Wittenberg (1511-1517) A. 1511, Luther relocates to the Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg; teaches at the university B. Frederick III building castle in Wittenberg, huge relic collection; first portrait of Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder; awarded a doctor of theology degree in 1512 at age 28; he taught Romans, Hebrews and Galatians; Tower experience of 1515 C. Indulgence controversy; Posts 95 Theses on Oct. 31, 1517; due to printing press, known all over Germany in period of two months IV. Luther and the Wider World (1518-1521) A. Audience with Cardinal Cajetin, Oct. 1518; released from monastic vows by Staupitz B. Leipzig Debate with Johann Eck, June 1519; Luther forced to clarify his views C. Wrote Babylonian Captivity of the Church and To the Christian Nobility of Germany, 1520 D. Excommunicated by Pope Leo X E. Refuses to recant at Diet of Worms, April 18, 1521; “kidnapped” and taken to Wartburg Castle Page 1 of 2 THE FUNDAMENTAL THEMES OF LUTHER’S REFORMS 1. -

Romanmonsterlookinside.Pdf

Habent sua fata libelli Early Modern Studies Series General Editor Michael Wolfe St. John’s University Editorial Board of Early Modern Studies Elaine Beilin Raymond A. Mentzer Framingham State College University of Iowa Christopher Celenza Charles G. Nauert Johns Hopkins University University of Missouri, Emeritus Barbara B. Diefendorf Max Reinhart Boston University University of Georgia Paula Findlen Robert V. Schnucker Stanford University Truman State University, Emeritus Scott H. Hendrix Nicholas Terpstra Princeton Theological Seminary University of Toronto Jane Campbell Hutchison Margo Todd University of Wisconsin– Madison University of Pennsylvania Mary B. McKinley James Tracy University of Virginia University of Minnesota Merry Wiesner- Hanks University of Wisconsin– Milwaukee The Roman Monster An Icon of the Papal Antichrist in Reformation Polemics LAWRENCE P. BUCK Early Modern Studies 13 Truman State University Press Kirksville, Missouri Copyright © 2014 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Roma caput mundi, reproduction of Roman Monster by Wenzel von Olmutz (1498); woodcut. Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Buck, Lawrence P. (Lawrence Paul), 1944– The Roman monster : an icon of the Papal Antichrist in Reformation polemics / by Lawrence P. Buck. pages cm. — (Early modern studies ; 13) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-106-7 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-107-4 (ebook) 1. Monsters—Religious aspects—Christianity—History. 2. Reformation. 3. Papacy—History. 4. Anti-Catholicism—History. 5. Antichrist in art. 6. Antichrist in literature. 7. End of the world—Biblical teaching. 8. Polemics—History. -

The Leipzig Debate Who Won? John Eck Or Martin Luther

The Leipzig Debate Who Won? John Eck or Martin Luther New Jersey Core Content Standards: 6.2.12.B.2.b: Relate the division of European regions during this time period into those that remained Catholic and those that became Protestant to the practice of religion in the New World. 6.2.12.D.2.b: Determine the factors that led to the Reformation and the impact on European politics. 6.2.12.D.2.e. Assess the impact of the printing press and other technologies developed on the dissemination of ideas. NY Global Studies Learning Standards: G2: 2. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses: the challenge to the power and authority of the Roman Catholic Church Common Core Standards: Reading in History 9-10:1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of information. Reading in History 9-10:2 Determine the central ideas of information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text. Reading in History 9-10:8 Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claims. Reading in History 11-12:1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole. Reading in History 11-12:2 Determine the central ideas of information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationship among key details and ideas. -

Practicing What He Preached : How Martin Luther Lived out His "Universal Priesthood of All Believers" David C

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Practicing what he preached : how Martin Luther lived out his "universal priesthood of all believers" David C. Mayes Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Mayes, David C., "Practicing what he preached : how Martin Luther lived out his "universal priesthood of all believers"" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 731. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRACTICING WHAT HE PREACHED: HOW MARTIN LUTHER LIVED OUT HIS "UNIVERSAL PRIESTHOOD OF ALL BELIEVERS" by DAVID CHRISTOPHER MAYES B.A., University of Richmond, 1994 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Richmond in Candidacy for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May, 1996 Richmond, Virginia LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA 23173 © Copyright by David Christopher Mayes 1996 All Rights Reserved I certify that I have read this thesis and find that, in scope and quality, it satisfies the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts. Dr. Barbara A. Sella readway THESIS ABSTRACT THESIS TITLE: Practicing What He Preached: How Martin Luther Lived Out His "Universal Priesthood of All Believers" AUTHOR: David Christopher Mayes DEGREE: Master of Arts INSTITUTION: University of Richmond YEAR DEGREE AWARDED: 1996 THESIS DIRECTOR: Dr. John R. Rilling When Martin Luther entered the monastery in 1505 as an Augustinian monk, he left the corrupted, inherently less-spiritual"world" for the religiously- oriented, celibate life in a cloister-the highest, most holy road one could take as a Christian.