Reformation 2017 Nikolaus Von Amsdorf Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concordia Theological Quarterly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 83:3–4 July/October 2019 Table of Contents After Canons, Councils, and Popes: The Implications of Luther’s Leipzig Debate for Lutheran Ecclesiology Richard J. Serina Jr. ...................................................................................... 195 The Leipzig Debate and Theological Method Roland F. Ziegler .......................................................................................... 213 Luther and Liberalism: A Tale of Two Tales (Or, A Lutheran Showdown Worth Having) Korey D. Maas .............................................................................................. 229 Scripture as Philosophy in Origen’s Contra Celsum Adam C. Koontz ........................................................................................... 237 Passion and Persecution in the Gospels Peter J. Scaer .................................................................................................. 251 Reclaiming Moral Reasoning: Wisdom as the Scriptural Conception of Natural Law Gifford A. Grobien ....................................................................................... 267 Anthropology: A Brief Discourse David P. Scaer ............................................................................................... 287 Reclaiming the Easter Vigil and Reclaiming Our Real Story Randy K. Asburry ......................................................................................... 325 Theological Observer ................................................................................................ -

Martin Luther

TRUTHmatters October 2002 Volume II, Issue 4 ous errors of John Wycliffe who said ‘It is not MARTIN LUTHER necessary for salvation to believe that the Ro- (This is the second of two articles) man Church is above all others.’ And you are espousing the pestilent errors of John Hus, We shift now to Luther’s work in the who claimed that Peter neither was nor is the following two to three years. It has already been head of the Holy Catholic Church.” mentioned that he was catapulted into the fore- This was dangerous ground for Luther ground and the next two or three years were to be on because John Hus had been burned as both hard and rewarding to the Augustinian a heretic and if Luther could be forced into this monk. I will only cover two of these most im- stand, he could also be called a heretic. A portant events. The Leipzig Debate in July of lunch break was due and during this break Lu- 1519 and the famous Diet of Worms in 1521. ther went to the library and quickly looked up The Leipzig debate was held in the large what Hus had believed and found that it was hall of the Castle of Pleissenberg at Leipzig. The exactly what he believed. In the afternoon ses- debate was between Johann Eck who repre- sion, Luther astonished the whole assembly by sented the Roman church and Dr. Carlstadt and declaring in effect: “Ja, Ich bin ein Hussite” or Dr. Martin Luther. It was a great intellectual “Yes, I am a Hussite.” It is from this debate battle that lasted three weeks. -

159 Philipp Melanchthon These Two Volumes, the Most Recent to Appear

Book Reviews 159 Philipp Melanchthon Briefwechsel Band t 16: Texte 4530–4790 (Januar–Juni 1547). Bearbeitet von Matthias Dall’Asta, Heidi Hein und Christine Mundhenk. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart/Bad Cannstatt 2015, 409 s. isbn 9783772825781. €298. Band t 17: Texte 4791–5010 (Juli–Dezember 1547). Bearbeitet von Matthias Dall’Asta, Heidi Hein und Christine Mundhenk. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart/Bad Cannstatt 2016, 356 s. isbn 9783772825798. €298. These two volumes, the most recent to appear in the edition of Melanchthon’s correspondence prepared by the Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, collect Melanchthon’s correspondence from the year 1547, the year following Luther’s death, during which the Schmalkaldic wars were raging. The edition is made up of two parts: the first “Register” [r] section, comprising eight vol- umes giving German summaries of the texts of the correspondence, a volume of addenda and cross-references, and a further five volumes of indices of places and people (of which the final two are in preparation). The second section, “Texts” [t] will comprise 30 volumes in total, following Melanchthon’s corre- spondence from 1514, when he was a seventeen-year-old student at the Univer- sity of Tübingen, to 1560, the year of his death. In total, Melanchthon’s correspondence includes nearly 9500 texts, written either by him or to him. For the year 1547, the total is over 500. Volume 16 col- lects 272 texts: 243 written by Melanchthon and 29 received by him. Volume 17 is made up of 232 texts, of which 201 were composed by Melanchthon, and 31 addressed to him. -

Defending Faith

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation herausgegeben von Volker Leppin (Tübingen) in Verbindung mit Amy Nelson Burnett (Lincoln, NE), Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Helmrath (Berlin), Matthias Pohlig (Münster) Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) 65 Timothy J. Wengert Defending Faith Lutheran Responses to Andreas Osiander’s Doctrine of Justification, 1551– 1559 Mohr Siebeck Timothy J. Wengert, born 1950; studied at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), Duke University; 1984 received Ph. D. in Religion; since 1989 professor of Church History at The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ISSN 1865-2840 (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2012 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Minion typeface, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements Thanks is due especially to Bernd Hamm for accepting this manuscript into the series, “Spätmittelalter, Humanismus und Reformation.” A special debt of grati- tude is also owed to Robert Kolb, my dear friend and colleague, whose advice and corrections to the manuscript have made every aspect of it better and also to my doctoral student and Flacius expert, Luka Ilic, for help in tracking down every last publication by Matthias Flacius. -

564158Eb19f006.65831545.Pdf

HEARTH AND HOME Left: Later Protestants liked to describe the Luthers as the ideal parsonage family. Here a 19th-c. artist imagines the family gathered around to sing with friend Melancthon in the background. DIABOLICAL BAGPIPES Below: Luther’s opponents caricatured him as merely a mouthpiece for the devil. Protestants countered that monks, not Luther, were the devil’s instruments. RSITY E Did you know? NIV U LUTHER LOVED TO PLAY THE LUTE, ONCE WENT ON STRIKE FROM HIS CONGREGATION, AND OGY, EMORY HATED TO COLLECT THE RENT ES F THEOL O VA L MAG I NE MAN MICHELANGELO, MUSIC, AND MASS E • Christopher Columbus set sail when Luther was a LER SCHOO schoolboy, and Michelangelo was completing his Sis- tine Chapel ceiling when Luther began teaching theol- REFORMATION, GE E RMANY / BRIDG RARY, CAND B TH ogy as a young man. SINGING CONGREGANTS, STRIKING PASTOR F • Luther preferred music to any other school subject, Luther made singing a central part of Protestant wor- OGY LI UM O OTHA, GE E G and he became very skilled at playing the lute. Upon ship. In his German Mass (1526), he dispensed with the US IN, THEOL E becoming a monk at age 21, he had to give the lute away. choir and assigned all singing to the congregation. He L M NST • When Luther celebrated his first Mass as a priest in often called congregational rehearsals during the week EDE RNATIONA 1507, he trembled so much he nearly dropped the bread so people could learn new hymns. TION, PITTS E NT OSS FRI and cup. -

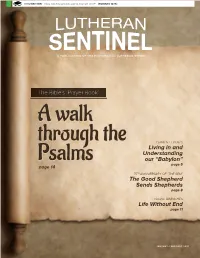

The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds Life Without End the Bible's

IT IS WRITTEN: “How can they preach, unless they are sent?” (ROMANS 10:15) A PUBLICATION OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD The Bible’s ‘Prayer Book’ A walk through the CURRENT EVENTS Living in and Understanding our “Babylon” Psalms page 5 page 14 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF “THE SEM” The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds page 8 YOUNG BRANCHES Life Without End page 11 JANUARY– FEBRUARY 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT: by REV. JOHN A. MOLDSTAD, President EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD, Mankato, Minn. HowVaporVapor Makes Plans Dear Members and Friends of our ELS: We know what happens when a glass of hot water is placed his ventures, and now he was doing even more expansion. outside on an icy morning. For a time, vapor rises when the When I interjected, “I guess the Lord has really blessed you,” heat meets the cold. Then it quickly disappears. That rising I could sense he felt momentarily uneasy. He did not speak vapor is used by the writer of James to have us reflect on at all of his accomplishments as gifts from God. He replied, the way we go about our lives in making plans. Planning for “Well, I don’t mean to be ‘brag-tocious’ but…” Then he quickly the new year – a year we pray will not repeat the pandemic launched into more of his lucrative plans. challenges of 2020 – needs always to consider what James wrote by inspiration of God the Holy Spirit: Now listen, you Could we also be guilty of the sin of boasting in a less obvious who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, way? Our sinful mind that we carry with us daily as unwanted spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” baggage tempts us to leave God out of the picture. -

159 Philipp Melanchthon These Two Volumes, the Most Recent to Appear

Book Reviews 159 Philipp Melanchthon Briefwechsel Band t 16: Texte 4530–4790 (Januar–Juni 1547). Bearbeitet von Matthias Dall’Asta, Heidi Hein und Christine Mundhenk. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart/Bad Cannstatt 2015, 409 s. isbn 9783772825781. €298. Band t 17: Texte 4791–5010 (Juli–Dezember 1547). Bearbeitet von Matthias Dall’Asta, Heidi Hein und Christine Mundhenk. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart/Bad Cannstatt 2016, 356 s. isbn 9783772825798. €298. These two volumes, the most recent to appear in the edition of Melanchthon’s correspondence prepared by the Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, collect Melanchthon’s correspondence from the year 1547, the year following Luther’s death, during which the Schmalkaldic wars were raging. The edition is made up of two parts: the first “Register” [r] section, comprising eight vol- umes giving German summaries of the texts of the correspondence, a volume of addenda and cross-references, and a further five volumes of indices of places and people (of which the final two are in preparation). The second section, “Texts” [t] will comprise 30 volumes in total, following Melanchthon’s corre- spondence from 1514, when he was a seventeen-year-old student at the Univer- sity of Tübingen, to 1560, the year of his death. In total, Melanchthon’s correspondence includes nearly 9500 texts, written either by him or to him. For the year 1547, the total is over 500. Volume 16 col- lects 272 texts: 243 written by Melanchthon and 29 received by him. Volume 17 is made up of 232 texts, of which 201 were composed by Melanchthon, and 31 addressed to him. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

Miadrilms Internationa! HOWLETT, DERQ

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated witli a round black mark it is an indication that the füm inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

HT504 HISTORY of CHRISTIANITY II Summer Semester 2010 Reformed Theological Seminary Orlando, FL Dr

HT504 HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY II Summer Semester 2010 Reformed Theological Seminary Orlando, FL Dr. W. Andrew Hoffecker The purpose of the course is to study Christian church history from the Protestant Reformation to the present. The course will be multifaceted and will include: the development of Christian theology such as the theologies of Luther, Calvin, Schleiermacher, and Barth; the institutional church; various views of the religious life including pietism and Puritanism; and prominent movements (e.g., Protestant scholasticism, modern liberalism and Neo Orthodoxy) and individuals who inspired them. Our aim, therefore, is not to limit our study to “church history” alone, but always as it is related to other fields in the history of Christian thought and the larger culture. By surveying diverse but related subjects, students will gain an overall historical perspective of the Church – its theology, institutions, and leaders during the last five centuries. Throughout our study the advantages of an integrated perspective will be stressed. The major benefits of this approach will be an increased appreciation of God's providential work throughout its history and insights into important issues of our own era. A principal interest will be to understand how people and ideas influenced the church of the past, and how they still affect contemporary events. COURSE REQUIREMENTS 1. TEXTS: The following texts are required for the course: Justo Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity: Vol 2 The Reformation to the Present Day; Hugh T. Kerr, Readings in Christian Thought. Students will read Gonzalez in its entirety; Kerr, pages 136-403. Students will also complete additional pages of reading which will be reported on the day of the final exam on the “READING REPORT FOR HT504” attached to this syllabus. -

Alexandra Harris

Harris 1 The 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation A Turning Point in World History Alexandra Harris “Who had the more convincing argument at the Leipzig Debate: John Eck or Martin Luther? During the time of the Protestant Reformation, an important event known as the Leipzig Debate occurred. This was primarily between two men with varying views on religion, Dr. Johann Eck and Martin Luther. The latter of these men was a German monk who was the father of Lutheranism, a branch of Christianity that emerged during the Protestant Reformation. John Eck was a German theologian who was friendly with Luther until 1517, which was when Luther published his Ninety-five Theses. Eck deemed these theses to be unorthodox and challenged Luther and one of his disciples to a debate on their differing views of religious doctrine. The Leipzig Debate took place in Germany in the year 1519, in the great hall of the castle named Pleissenburg, which is in Leipzig. A year before this, in 1518, this public debate was initiated by Johann Eck, who challenged both Andreas Rudolf Bodenstein von Karlstadt and Martin Luther to a debate on Luther's teachings. The discussion between Eck and Luther took place on the dates of July 4 - July 13, during which Luther emphasized his belief of faith in God alone; this stance can be backed up by scripture. John Eck defended Catholic doctrine and walked away the winner of the debate, according to the theologians of the University of Leipzig. Despite the ruling of the University of Leipzig, Martin Luther had the more convincing argument at the Leipzig Debate because he had superior knowledge of background information, he defended doctrine that remains true to the teachings of the Holy Bible, and he won over many new followers. -

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION at 500 YEARS from RUPTURE to DIALOGUE Jaume Botey

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AT 500 YEARS FROM RUPTURE TO DIALOGUE Jaume Botey 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 2. Luther’s personality and the theme of justification ...................... 7 3. The great controversies, and the progressive development of his thought ................................................................. 10 4. The great treatises of 1520 and the diet of worms .......................... 16 5. The peasants’ war .................................................................................... 21 6. Consolidation of the reformation ....................................................... 24 7. Epilogue .................................................................................................... 28 Notes ............................................................................................................. 31 Bibliography ................................................................................................. 32 In memory… In February, while we were preparing the English edition of this booklet, its author, Jaume Botey Vallés, passed away. As a member of the Cristianisme i Justícia team, Jaume was a person profoundly committed to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, and he worked energetically for peace and for the other world that is possible. Jaume, we will miss you greatly. Cristianisme i Justícia Jaume Botey has a licentiate in philosophy and theology and a doctorate in anthropology. He has been a professor of