Alexandra Harris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concordia Theological Quarterly

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 83:3–4 July/October 2019 Table of Contents After Canons, Councils, and Popes: The Implications of Luther’s Leipzig Debate for Lutheran Ecclesiology Richard J. Serina Jr. ...................................................................................... 195 The Leipzig Debate and Theological Method Roland F. Ziegler .......................................................................................... 213 Luther and Liberalism: A Tale of Two Tales (Or, A Lutheran Showdown Worth Having) Korey D. Maas .............................................................................................. 229 Scripture as Philosophy in Origen’s Contra Celsum Adam C. Koontz ........................................................................................... 237 Passion and Persecution in the Gospels Peter J. Scaer .................................................................................................. 251 Reclaiming Moral Reasoning: Wisdom as the Scriptural Conception of Natural Law Gifford A. Grobien ....................................................................................... 267 Anthropology: A Brief Discourse David P. Scaer ............................................................................................... 287 Reclaiming the Easter Vigil and Reclaiming Our Real Story Randy K. Asburry ......................................................................................... 325 Theological Observer ................................................................................................ -

Martin Luther

TRUTHmatters October 2002 Volume II, Issue 4 ous errors of John Wycliffe who said ‘It is not MARTIN LUTHER necessary for salvation to believe that the Ro- (This is the second of two articles) man Church is above all others.’ And you are espousing the pestilent errors of John Hus, We shift now to Luther’s work in the who claimed that Peter neither was nor is the following two to three years. It has already been head of the Holy Catholic Church.” mentioned that he was catapulted into the fore- This was dangerous ground for Luther ground and the next two or three years were to be on because John Hus had been burned as both hard and rewarding to the Augustinian a heretic and if Luther could be forced into this monk. I will only cover two of these most im- stand, he could also be called a heretic. A portant events. The Leipzig Debate in July of lunch break was due and during this break Lu- 1519 and the famous Diet of Worms in 1521. ther went to the library and quickly looked up The Leipzig debate was held in the large what Hus had believed and found that it was hall of the Castle of Pleissenberg at Leipzig. The exactly what he believed. In the afternoon ses- debate was between Johann Eck who repre- sion, Luther astonished the whole assembly by sented the Roman church and Dr. Carlstadt and declaring in effect: “Ja, Ich bin ein Hussite” or Dr. Martin Luther. It was a great intellectual “Yes, I am a Hussite.” It is from this debate battle that lasted three weeks. -

Balthasar Hubmaier and the Authority of the Church Fathers

Balthasar Hubmaier and the Authority of the Church Fathers ANDREW P. KLAGER In Anabaptist historical scholarship, the reluctance to investigate the authority of the church fathers for individual sixteenth-century Anabaptist leaders does not appear to be intentional. Indeed, more pressing issues of a historiographical and even apologetical nature have been a justifiable priority, 1 and soon this provisional Anabaptist vision was augmented by studies assessing the possibility of various medieval chronological antecedents. 2 However, in response to Kenneth Davis’ important study, Anabaptism and Asceticism , Peter Erb rightly observed back in 1976 that “. one must not fail to review the abiding influence of the Fathers . [whose] monitions were much more familiar to our sixteenth-century ancestors than they are to us.” 3 Over thirty years later, the Anabaptist community still awaits its first published comprehensive study of the reception of the church fathers among Anabaptist leaders in the sixteenth century. 4 A natural place to start, however, is the only doctor of theology in the Anabaptist movement, Balthasar Hubmaier. In the final analysis, it becomes evident that Hubmaier does view the church fathers as authoritative, contextually understood, for some theological issues that were important to him, notably his anthropology and understanding of the freedom of the will, while he acknowledged the value of the church fathers for the corollary of free will, that is, believers’ baptism, and this for apologetico-historical purposes. This authority, however, cannot be confused with an untested, blind conformity to prescribed precepts because such a definition of authority did not exist in the sixteenth-century, even among the strongest Historical Papers 2008: Canadian Society of Church History 134 Balthasar Hubmaier admirers of the fathers. -

“Here I Stand” — the Reformation in Germany And

Here I Stand The Reformation in Germany and Switzerland Donald E. Knebel January 22, 2017 Slide 1 1. Later this year will be the 500th anniversary of the activities of Martin Luther that gave rise to what became the Protestant Reformation. 2. Today, we will look at those activities and what followed in Germany and Switzerland until about 1555. 3. We will pay particular attention to Luther, but will also talk about other leaders of the Reformation, including Zwingli and Calvin. Slide 2 1. By 1500, the Renaissance was well underway in Italy and the Church was taking advantage of the extraordinary artistic talent coming out of Florence. 2. In 1499, a 24-year old Michelangelo had completed his famous Pietà, commissioned by a French cardinal for his burial chapel. Slide 3 1. In 1506, the Church began rebuilding St. Peter’s Basilica into the magnificent structure it is today. 2. To help pay for such masterpieces, the Church had become a huge commercial enterprise, needing a lot of money. 3. In 1476, Pope Sixtus IV had created a new market for indulgences by “permit[ing] the living to buy and apply indulgences to deceased loved ones assumed to be suffering in purgatory for unrepented sins.” Ozment, The Age of Reform: 1250-1550 at 217. 4. By the time Leo X became Pope in 1513, “it is estimated that there were some two thousand marketable Church jobs, which were literally sold over the counter at the Vatican; even a cardinal’s hat might go to the highest bidder.” Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church at 198. -

564158Eb19f006.65831545.Pdf

HEARTH AND HOME Left: Later Protestants liked to describe the Luthers as the ideal parsonage family. Here a 19th-c. artist imagines the family gathered around to sing with friend Melancthon in the background. DIABOLICAL BAGPIPES Below: Luther’s opponents caricatured him as merely a mouthpiece for the devil. Protestants countered that monks, not Luther, were the devil’s instruments. RSITY E Did you know? NIV U LUTHER LOVED TO PLAY THE LUTE, ONCE WENT ON STRIKE FROM HIS CONGREGATION, AND OGY, EMORY HATED TO COLLECT THE RENT ES F THEOL O VA L MAG I NE MAN MICHELANGELO, MUSIC, AND MASS E • Christopher Columbus set sail when Luther was a LER SCHOO schoolboy, and Michelangelo was completing his Sis- tine Chapel ceiling when Luther began teaching theol- REFORMATION, GE E RMANY / BRIDG RARY, CAND B TH ogy as a young man. SINGING CONGREGANTS, STRIKING PASTOR F • Luther preferred music to any other school subject, Luther made singing a central part of Protestant wor- OGY LI UM O OTHA, GE E G and he became very skilled at playing the lute. Upon ship. In his German Mass (1526), he dispensed with the US IN, THEOL E becoming a monk at age 21, he had to give the lute away. choir and assigned all singing to the congregation. He L M NST • When Luther celebrated his first Mass as a priest in often called congregational rehearsals during the week EDE RNATIONA 1507, he trembled so much he nearly dropped the bread so people could learn new hymns. TION, PITTS E NT OSS FRI and cup. -

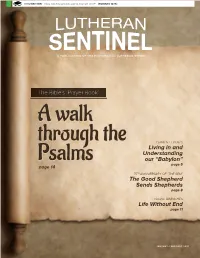

The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds Life Without End the Bible's

IT IS WRITTEN: “How can they preach, unless they are sent?” (ROMANS 10:15) A PUBLICATION OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD The Bible’s ‘Prayer Book’ A walk through the CURRENT EVENTS Living in and Understanding our “Babylon” Psalms page 5 page 14 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF “THE SEM” The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds page 8 YOUNG BRANCHES Life Without End page 11 JANUARY– FEBRUARY 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT: by REV. JOHN A. MOLDSTAD, President EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD, Mankato, Minn. HowVaporVapor Makes Plans Dear Members and Friends of our ELS: We know what happens when a glass of hot water is placed his ventures, and now he was doing even more expansion. outside on an icy morning. For a time, vapor rises when the When I interjected, “I guess the Lord has really blessed you,” heat meets the cold. Then it quickly disappears. That rising I could sense he felt momentarily uneasy. He did not speak vapor is used by the writer of James to have us reflect on at all of his accomplishments as gifts from God. He replied, the way we go about our lives in making plans. Planning for “Well, I don’t mean to be ‘brag-tocious’ but…” Then he quickly the new year – a year we pray will not repeat the pandemic launched into more of his lucrative plans. challenges of 2020 – needs always to consider what James wrote by inspiration of God the Holy Spirit: Now listen, you Could we also be guilty of the sin of boasting in a less obvious who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, way? Our sinful mind that we carry with us daily as unwanted spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” baggage tempts us to leave God out of the picture. -

Quellen Und Forschungen Aus Italienischen Bibliotheken Und Archiven

Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Bibliotheken und Archiven Bd. 75 1995 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publi- kationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswis- senschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Her- unterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträ- ger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu priva- ten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hin- ausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weiter- gabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. LUTHERGEGNER DER ERSTEN STUNDE Motive und Verflechtungen1 von GÖTZ-RÜDIGER TEWES Einleitung Personen, die in keiner historischen Darstellung bisher ihren ge bührenden Platz gefunden haben, stehen im Mittelpunkt dieser Stu die. Sie haben, aus unserer eingeschränkten Sicht, vielfach im Verbor genen gearbeitet. Doch ihr Handeln in Rom, Augsburg oder Köln er folgte an Schauplätzen welthistorischer Tragweite - wenn man der Reformationsgeschichte, ihrer Vor- und Frühphase, dieses Attribut.zu- erkennen möchte. An der Seite einiger Lichtgestalten unter den Lu thergegnern haben sie gewirkt, und gerade deren Handeln zeigt sich so in bisher übersehenen Verbindungen. Die Spurensuche erwies sich als mühsam; auf die Bereitschaft, den einzelnen Fährten zu folgen, sich mit vielen unbekannten Personen vertraut zu machen, wird sich 1 Folgende Abkürzungen werden benutzt: Archive und Bibliotheken: ASV = Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Rom - Arm. = Armarium, IE = Introitus et Exitus, Reg. Lat. = Registra Lateranensia, Reg. Vat. = Registra Vaticana; BAV = Biblio teca Apostolica Vaticana, Rom; ASt = Archivio di Stato, Rom; AEK = Archiv des Erzbistums Köln; HAStK = Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln; StAA = Stadtarchiv Augsburg. -

Johann Tetzel in Order to Pay for Expanding His Authority to the Electorate of Mainz

THE IMAGE OF A FRACTURED CHURCH AT 500 YEARS CURATED BY DR. ARMIN SIEDLECKI FEB 24 - JULY 7, 2017 THE IMAGE OF A FRACTURED CHURCH AT 500 YEARS Five hundred years ago, on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses, a series of statements and proposals about the power of indulgences and the nature of repentance, forgiveness and salvation. Originally intended for academic debate, the document quickly gained popularity, garnering praise and condemnation alike, and is generally seen as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. This exhibit presents the context of Martin Luther’s Theses, the role of indulgences in sixteenth century religious life and the use of disputations in theological education. Shown also are the early responses to Luther’s theses by both his supporters and his opponents, the impact of Luther’s Reformation, including the iconic legacy of Luther’s actions as well as current attempts by Catholics and Protestants to find common ground. Case 1: Indulgences In Catholic teaching, indulgences do not effect the forgiveness of sins but rather serve to reduce the punishment for sins that have already been forgiven. The sale of indulgences was initially intended to defray the cost of building the Basilica of St. Peter in Rome and was understood as a work of charity, because it provided monetary support for the church. Problems arose when Albert of Brandenburg – a cardinal and archbishop of Magdeburg – began selling indulgences aggressively with the help of Johann Tetzel in order to pay for expanding his authority to the Electorate of Mainz. 2 Albert of Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz Unused Indulgence (Leipzig: Melchior Lotter, 1515?) 1 sheet ; 30.2 x 21 cm. -

Proquest Dissertations

Pestilence and Reformation: Catholic preaching and a recurring crisis in sixteenth-century Germany Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Frymire, John Marshall Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:47:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279789 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Ecce Fides Pillar of Truth

Ecce Fides Pillar of Truth Fr. John J. Pasquini TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication Foreword Introduction Chapter I: The Holy Scriptures and Tradition Where did the Bible come from? Would Jesus leave us in confusion? The Bible alone is insufficient and unchristian What Protestants can’t answer! Two forms of Revelation What about Revelation 22:18-19? Is all Scripture to be interpreted in the same way? Why was the Catholic Church careful in making Bibles available to individual believers? Why do Catholics have more books in the Old Testament than Protestants or Jews? Chapter II: The Church Who’s your founder? Was Constantine the founder of the Catholic Church? Was there a great apostasy? Is the Catholic Church the “Whore of Babylon”? Who founded the Church in Rome? Peter, the Rock upon which Jesus built his Church! Are the popes antichrists? Why is the pope so important? Without the popes, the successors of St. Peter, there would be no authentic Christianity! Why is apostolic succession so important? The gates of hell will not prevail against it! The major councils of the Church and the assurance of the true faith! Why is there so much confusion in belief among Protestants? What gave rise to the birth of Protestantism? Chapter III: Sacraments Are sacraments just symbols? What do Catholics mean by being “born again” and why do they baptize children? Baptism by blood and desire for adults and infants Does baptism require immersion? Baptism of the dead? Where do we find the Sacrament of Confirmation? Why do Catholics believe the Eucharist is the -

Studies in REFORMED THEOLOGY and HISTORY

Studies in REFORMED THEOLOGY AND HISTORY AUDENS n VlVtaS Volume 1 Number 1 Winter 1993 PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Studies in REFORMED THEOLOGY AND HISTORY AftDfNS O VlVWS EDITORIAL COUNCIL CHAIR Thomas W. Gillespie EDITOR David Willis-Watkins EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Barbara Chaapel Sang Lee Ronald de Groot Elsie McKee Jane Dempsey Douglass Daniel Migliore Nancy Duff James Moorhead William Harris John Wilson EDITORIAL COUNCIL Edward Dowey 1995 Wilhelm Neuser Dawn de Vries Jung Song Rhee Richard Gamble Thomas Torrance John Leith Nicholas Wolterstorff Brian Armstrong 1998 Heiko Oberman Fritz Biisser Janos Pasztor Brian Gerrish Leanne Van Dyk Robert Kingdon Nobuo Watanabe Irena Backus 2001 Bernard Roussel John de Gruchy Jean-Loup Seban John Hesselink Willem van ’t Spijker William Klempa Michael Welker Editorial Offices Princeton Theological Seminary, CN 821, Princeton, NJ 08542-0803 fax (609) 497-7728 v/ Is I THE DISPUTATIONS OF BADEN, 1526 AND BERNE, 1528: Neutralizing the Early Church Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 with funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library https://archive.org/details/studiesinreforme11prin THE DISPUTATIONS OF BADEN, 1526 AND BERNE, 1528: Neutralizing the Early Church IRENA BACKUS ARDENS VlVWS PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Studies in Reformed Uieology and History is published four times annually by Princeton Theological Seminary. All correspondence should be addressed to David Willis-Watkins, Editor, Studies in Reformed Theology and History, CN 821, Princeton, NJ 08542 0803, USA. Fax (609) 497-7728. MANUSCRIPT SUBMISSIONS Contributions to Studies in Reformed Theology and History are invited. Copies of printed and electronic manuscript requirements are available upon request from the Editor at the above address. -

The Age of Reformation

CHAPTER 13 The Age of Reformation CHAPTER OUTLINE • Prelude to Reformation: The Northern Renaissance • Prelude to Reformation: Church and Religion on the Eve of the Reformation • Martin Luther and the Reformation in Germany • Germany and the Reformation: Religion and Politics • The Spread of the Protestant Reformation • The Social Impact of the Protestant Reformation • The Catholic Reformation • Conclusion FOCUS QUESTIONS • Who were the Christian humanists, and how did they differ from the L Protestant reformers? • What were Martin Luther’s main disagreements with the Roman Catholic church, and why did the movement he began spread so quickly across Europe? • What were the main tenets of Lutheranism, Zwinglianism, Calvinism, and Anabaptism, and how did they differ from each other and from Catholicism? • What impact did the Protestant Reformation have on the society of the sixteenth century? • What measures did the Roman Catholic church take to reform itself and to combat Protestantism in the sixteenth century? N APRIL 18, 1520, a lowly monk stood before the emperor and princes of Germany in the city of Worms. He had been Ocalled before this august gathering to answer charges of heresy, charges that could threaten his very life. The monk was confronted with a pile of his books and asked if he wished to defend them all or reject a part. Courageously, Martin Luther defended them all and asked to be shown where any part was in error on the basis of “Scripture and plain rea- son.” The emperor was outraged by Luther’s response and made his own position clear the next day: “Not only I, but you of this noble Ger- man nation, would be forever disgraced if by our negligence not only heresy but the very suspicion of heresy were to survive.