Download Social Science Our Pasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Energy Education Society Study Material Class-VIII Subject- History Lesson 05-When People Rebel: 1857 and After Module

Atomic Energy Education Society Study material Class-VIII Subject- History Lesson 05-When People Rebel: 1857 and After Module- 2/2 Important points The Rebellion Spreads : The British had initially taken the revolt at Meerut quite lightly. But the decision by Bahadur Shah Zafar to support the rebellion had dramatically changed the entire situation. People were emboldened by an alternative possibility. The British were routed from Delhi, and for almost a week there was no uprising. The rebellion in Delhi took almost a week to spread as news over whole of the India. Many regiments mutinied one after another at various places such as Delhi, Kanpur and Lucknow. People of the towns and the villages also rose up in rebellion and rallied around local leaders. Zamindars and chiefs were prepared to establish their authority and fight the British. Nanasaheb Peshwa gathered armed forces and expelled the British garrison in Kanpur. He proclaimed himself the Peshwa. He declared that he was a governor under Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. Birjis Qadr, the son of Nawab Wajid Ali shah, was proclaimed the new Nawab. He too acknowledged suzerainty of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Begum Hazrat Mahal took an active part in organizing the uprising against the British. In Jhansi, Rani Lakshmibai joined the rebel Sepoys and fought the British along with Tantia Tope. The General of Nana Saheb. Ahmadullah Shah a maulvi from Faizabad prophesied that the rule of the British would come to an end he caught the imagination of the people and raised a huge force of supporters. He came to Lucknow to fight the Britishers. -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Top 200 Questions of History

Top 200 Questions of History Top 200 Questions of History 1. Twenty Point Programme was launched in 1975 by – Indira Gandhi 2. The famous Quit India Resolution was passed on? August 8, 1942 3. Which university can be considered as an epitome of education in the Gupta Dynasty? Nalanda University 4. During the Mughal period, which trader was the first to come to India? Portuguese 5. Akbar’s guardian teacher was – Bairam Khan 6. International boundary between India and Pakistan is demarcated by – Radcliffe Line 7. The Dal Khalsa was founded by? Kapur Singh 8. The Governor-General was given the power to issue ordinances by the act of? Indian Councils Act ,1861 9. The High Commissioner for India in the United Kingdom must be appointed by __________? The Government of India 10. As per Act of 1919 the lower house of the Central Legislature was known as __________? Legislative Assembly 11. Who had become the first Governor-General of India after independence? Lord Mountbatten 12. What was the type of marriage in the Vedic period in which, in place of the dowry, there was a token bride price of a cow and a bull? Arsa Top 200 Questions of History 13. Who was the Greek ambassador in the court of Chandragupta Maurya? Megasthanes 14. Who constructed the 84 thousands Stupa? Ashoka 15. Jahangir (1605–1627 AD) was the ruler of which dynasty? Mughal 16. Who pioneered the guerrilla warfare methods? Shivaji 17. UNESCO Cultural World Heritage site Humayun Tomb’s construction completed in – 1572 AD 18. In Akbar's regime, _____ was the military head. -

CC-12:HISTORY of INDIA(1750S-1857) II.EXPANSION and CONSOLIDATION of COLONIAL POWER

CC-12:HISTORY OF INDIA(1750s-1857) II.EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION OF COLONIAL POWER: (A) MERCANTILISM,FOREIGN TRADE AND EARLY FORMS OF EXTRACTION FROM BENGAL The coming of the Europeans to the Indian subcontinent was an event of great significance as it ultimately led to revolutionary changes in its destiny in the future. Europe’s interest in India goes back to the ancient times when lucrative trade was carried on between India and Europe. India was rich in terms of spices, textile and other oriental products which had huge demand in the large consumer markets in the west. Since the ancient time till the medieval period, spices formed an important part of European trade with India. Pepper, ginger, chillies, cinnamon and cloves were carried to Europe where they fetched high prices. Indian silk, fine Muslin and Indian cotton too were much in demand among rich European families. Pearls and other precious stone also found high demand among the European elites. Trade was conducted both by sea and by land. While the sea routes opened from the ports of the western coast of India and went westward through the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Alexandria and Constantinople, Indian trade goods found their way across the Mediterranean to the commercials hubs of Venice and Genoa, from where they were then dispersed throughout the main cities of Europe. The old trading routes between the east and the west came under Turkish control after the Ottoman conquest of Asia Minor and the capture of Constantinople in1453.The merchants of Venice and Genoa monopolised the trade between Europe and Asia and refused to let the new nation states of Western Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, have any share in the trade through these old routes. -

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Subject: History Unit: Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Lesson: Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Lesson Developer : Prof. Lakshmi Subramanian College/Department : Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Table of contents Chapter 2: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power • 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power • Summary • Exercises • Glossary • Further readings Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Introduction The second half of the 18th century saw the formal induction of the English East India Company as a power in the Indian political system. The battle of Plassey (1757) followed by that of Buxar (1764) gave the Company access to the revenues of the subas of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a subsequent edge in the contest for paramountcy in Hindustan. Control over revenues resulted in a gradual shift in the orientation of the Company’s agenda – from commerce to land revenue – with important consequences. This chapter will trace the development of the Company’s rise to power in Bengal, the articulation of commercial policies in the context of Mercantilism that developed as an informing ideology in Europe and that found limited application in India by some of the Company’s officials. This found expression until the 1750’s in the form of trade privileges, differential customs payments and fortifications of Company settlements all of which combined to produce an alternative nucleus of power within the late Mughal set up. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Chapter-Iii Revolt of 1857 and Muslims

CHAPTER-III REVOLT OF 1857 AND MUSLIMS Since the time it erupted, all historians have been engaged in the futile exercise of labelling the Uprising of 1857 with some descriptive word or other- such as “mutiny”, “revolt”, “revolution”, “national war”, etc. Anyone starting with a preconceived notion is likely to fall into confusion, and even those who try to be most objective and start, as it were, with a blank sheet are not immune from confusion owing to the elusive nature of the Uprising. Nearly everyone of them is partly right as long as he deals with a particular aspect of the events of 1857 in a particular time or region; but they all go wrong when they begin to generalize. In fact, seen from a particular angle, it was indeed, as the British called it, a mutiny of the sepoys, but when it spread among civilians involving different sections, it assumed the character of a civil rebellion or revolt. And since the aim of the revolt was to overthrow alien rule, we discern in it an unconscious and sudden manifestation of national feeling or sentiment.1 If we regard communal harmony as the essential condition of a national uprising, we could, ignoring other conditions, justly regard 1857 as the year of the first spontaneous national uprising in India. In India the concept of nationalism evolved gradually and passed through various phases. We may, therefore, say that 1857 was the first phase, a beginning, however frail, of nationalism. Strictly it would not be right to think in terms of the European concept of nationalism in the Indian situation. -

Popular Resistance to the British Rule MODULE - 1 India and the World Through Ages

Popular Resistance to the British Rule MODULE - 1 India and the World through Ages 7 POPULAR RESISTANCE TO THE Notes BRITISH RULE British colonial rule had a tremendous impact on all sections of Indian society. Can you imagine being ruled by some strangers year after year? No, we cannot. Most of us were born after 1947 when India had already become independent. Do you know when the British conquered India and colonised its economy they faced stiff resistance from the people. There were a series of civil rebellions. These rebellions were led by rulers who were deposed by the Britishers, ex-officials of the conquered Indian states, impoverished zamindars and poligars. It brought together people having different ethnic, religious and class background against the British rule. In this lesson, we will read about some important popular uprisings, their nature and significance. We will also read about the uprising of 1857 which had a major impact on our National Movement. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: l discuss the causes of the popular resistance movements against the colonial rule before 1857; l explain the nature and significance of the peasant and tribal revolts; l identify the issues that led to the Revolt of 1857; and l analyse the importance and significance of the Revolt of 1857. 7.1 THE EARLY POPULAR RESISTANCE MOVEMENTS AGAINST COLONIAL RULE (1750-1857) Can you think of a reason why these resistance movements are called popular? Was it because of the large number of people who participated in them? Or was it because of the success they met with? After reading this section you will be able to arrive at a conclusion. -

St. Lawrence High School 27, Ballygunge Circular Road

3/24/2021 Entab - CampusCare®| School ERP Software ST. LAWRENCE HIGH SCHOOL 27, BALLYGUNGE CIRCULAR ROAD ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Class : 8 Subject : HISTORY Term : FIRST TERM Max Marks : 60 Q 1 : Which invader took away the Peacock Throne of Shah Jahan? Marks : 1 1 . Ahmad Shah Abdali 2 . Shah Jahan 3 . Nadir Shah ( This Answer is Correct ) 4 . Mahmud of Ghazni ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Q 2 : Who was required to maintain a fixed quota of troops? Marks : 1 1 . Jagirdars 2 . Nobles 3 . Kings 4 . Mansabdars ( This Answer is Correct ) ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Q 3 : In which year did Chin Qilich Khan carve out the state of Hyderabad? Marks : 1 1 . 1724 ( This Answer is Correct ) 2 . 1768 3 . 1718 4 . 1719 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Q 4 : Who was Govind Singh? Marks : 1 1 . Sikh Guru ( This Answer is Correct ) 2 . Brahmin Guru 3 . Muslim Guru 4 . Jain Guru ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Q 5 : Who was Banda Bahadur? Marks : 1 1 . Nizam ruler 2 . English ruler 3 . Sikh ruler ( This Answer is Correct ) 4 . Jain ruler ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Battle of Buxar 1764 - UPSC Mains History

Battle of Buxar 1764 - UPSC Mains History With the advent of Europeans in India, the British East India Company gradually conquered Indian territories. The Battle of Buxar is one such confrontation between the British army and their Indian counterparts which paved the way for the British to rule over India for the next 183 years. The Battle of Buxar took place in 1764 and is an important chapter in Indian Modern History for the IAS Exam. This article will talk about the Battle of Buxar in detail to help UPSC aspirants understand it for the mains examination. You can also download the Battle of Buxar notes PDF from the link provided. What was the Battle of Buxar? It was a battle fought between the English Forces, and a joint army of the Nawab of Oudh, Nawab of Bengal, and the Mughal Emperor. The battle was the result of misuse of trade privileges granted by the Nawab of Bengal and also the colonialist ambitions of East India Company Background of the Battle of Buxar Before the battle of Buxar, one more battle was fought. It was the Battle of Plassey, that gave the British a firm foothold over the region of Bengal. As a result of the Battle of Plassey, Siraj-Ud-Daulah was dethroned as the Nawab of Bengal and was replaced by Mir Jafar (Commander of Siraj's Army.) After Mir Jafar became the new Bengal nawab, the British made him their puppet but Mir Jafar got involved with Dutch East India Company. Mir Qasim (son-in-law of Mir Jafar) was supported by the British to become the new Nawab and under the pressure of the Company, Mir Jafar decided to resign in favour of Mir Kasim. -

The Revolt of 1857

1A THE REVOLT OF 1857 1. Objectives: After going through this unit the student wilt be able:- a) To understand the background of the Revolt 1857. b) To explain the risings of Hill Tribes. c) To understand the causes of The Revolt of 1857. d) To understand the out Break and spread of the Revolt of 1857. e) To explain the causes of the failure of the Revolt of 1857. 2. Introduction: The East India Company's rule from 1757 to 1857 had generated a lot of discontent among the different sections of the Indian people against the British. The end of the Mughal rule gave a psychological blow to the Muslims many of whom had enjoyed position and patronage under the Mughal and other provincial Muslim rulers. The commercial policy of the company brought ruin to the artisans and craftsman, while the divergent land revenue policy adopted by the Company in different regions, especially the permanent settlement in the North and the Ryotwari settlement in the south put the peasants on the road of impoverishment and misery. 3. Background: The Revolt of 1857 was a major upheaval against the British Rule in which the disgruntled princes, to disconnected sepoys and disillusioned elements participated. However, it is important to note that right from the inception of the East India Company there had been resistance from divergent section in different parts of the sub continent. This resistance offered by different tribal groups, peasant and religious factions remained localized and ill organized. In certain cases the British could putdown these uprisings easily, in other cases the struggle was prolonged resulting in heavy causalities. -

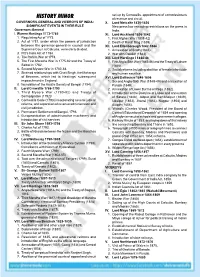

HISTORY MINOR of Revenue and Circuit

set up by Cornwallis, appointment of commissioners HISTORY MINOR of revenue and circuit. GOVERNORS-GENERAL AND VICEROYS OF INDIA : X. Lord Metcalfe 1835-1836 SIGNIFICANT EVENTS IN THEIR RULE New press law removing restrictions on the press in Governors-General India. I. Warren Hastings 1773-1785 XI. Lord Auckland 1836-1842 1. Regulating Act of 1773. 1. First Afghan War (1838-42) 2. Act of 1781, under which the powers of jurisdiction 2. Death of Ranjit Sing (1839). between the governor-general-in council and the XII. Lord Ellenborough 1842-1844 Supreme Court at Calcutta, were clerly divided. 1. Annexation of Sindh (1843). 3. Pitt's India Act of 1784. 2. War with Gwalior (1843). 4. The Rohilla War of 1774. XIII. Lord Hardinge I 1844-48 5. The First Maratha War in 1775-82 and the Treaty of 1. First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-46) and the Treaty of Lahore Salbai in 1782. (1846). 6. Second Mysore War in 1780-84. 2. Social reforms including abolition of female infanticide 7. Strained relationships with Chait Singh, the Maharaja and human sacrifice. of Benaras, which led to Hastings' subsequent XVI. Lord Dalhousie 1848-1856 impeachment in England. 1. Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49) and annexation of 8. foundation of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1784). Punjab (1849). II. Lord Crnwallis 1786-1793 2. Annexation of Lower Burma or Pegu (1852). 1. Third Mysore War (1790-92) and Treaty of 3. Introduction of the Doctrine of Lapse and annexation Seringapatam (1792)/ of Satara (1848), Jaitpur and Sambhalpur (1849), 2. Cornwallis Code (1793) incorporating several judicial Udaipur (1852), Jhansi (1853), Nagpur (1854) and reforms, and separation of revenue administration and Awadh (1856).