Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

Spatial Semantics, Case and Relator Nouns in Evenki

Spatial semantics, case and relator nouns in Evenki Lenore A. Grenoble University of Chicago Evenki, a Northwest Tungusic language, exhibits an extensive system of nominal cases, deictic terms, and relator nouns, used to signal complex spatial relations. The paper describes the use and distribution of the spatial cases which signal stative and dynamic relations, with special attention to their semantics within a framework using fundamental Gestalt concepts such as Figure and Ground, and how they are used in combination with deictics and nouns to signal specific spatial semantics. Possible paths of grammaticalization including case stacking, or Suffixaufnahme, are dis- cussed. Keywords: spatial cases, case morphology, relator noun, deixis, Suf- fixaufnahme, grammaticalization 1. Introduction Case morphology and relator nouns are extensively used in the marking of spa- tial relations in Evenki, a Tungusic language spoken in Siberia by an estimated 4802 people (All-Russian Census 2010). A close analysis of the use of spatial cases in Evenki provides strong evidence for the development of complex case morphemes from adpositions. Descriptions of Evenki generally claim the exist- ence of 11–15 cases, depending on the dialect. The standard language is based on the Poligus dialect of the Podkamennaya Tunguska subgroup, from the Southern dialect group, now moribund. Because it forms the basis of the stand- ard (or literary) language and as such has been relatively well-studied and is somewhat codified, it usually serves as the point of departure in linguistic de- scriptions of Evenki. However, the written language is to a large degree an artifi- cial construct which has never achieved usage in everyday conversation: it does not function as a norm which cuts across dialects. -

Elevation As a Category of Grammar: Sanzhi Dargwa and Beyond Received May 11, 2018; Revised August 20, 2018

Linguistic Typology 2019; 23(1): 59–106 Diana Forker Elevation as a category of grammar: Sanzhi Dargwa and beyond https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2019-0001 Received May 11, 2018; revised August 20, 2018 Abstract: Nakh-Daghestanian languages have encountered growing interest from typologists and linguists from other subdiscplines, and more and more languages from the Nakh-Daghestanian language family are being studied. This paper provides a grammatical overview of the hitherto undescribed Sanzhi Dargwa language, followed by a detailed analysis of the grammaticalized expression of spatial elevation in Sanzhi. Spatial elevation, a topic that has not received substantial attention in Caucasian linguistics, manifests itself across different parts of speech in Sanzhi Dargwa and related languages. In Sanzhi, elevation is a deictic category in partial opposition with participant- oriented deixis/horizontally-oriented directional deixis. This paper treats the spatial uses of demonstratives, spatial preverbs and spatial cases that express elevation as well as the semantic extension of this spatial category into other, non-spatial domains. It further compares the Sanzhi data to other Caucasian and non-Caucasian languages and makes suggestions for investigating elevation as a subcategory within a broader category of topographical deixis. Keywords: Sanzhi Dargwa, Nakh-Daghestanian languages, elevation, deixis, demonstratives, spatial cases, spatial preverbs 1 Introduction Interest in Nakh-Daghestanian languages in typology and in other linguistic subdisciplines has grown rapidly in recent years, with an active community of linguists from Russia and other countries. The goal of the present paper is to pour more oil into this fire and perhaps to entice new generations of scholars to join the throng. -

1 Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan

Tsezian Languages Bernard Comrie, Maria Polinsky, and Ramazan Rajabov Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany University of California, San Diego, USA Makhachkala, Russia 1. Sociolinguistic Situation1 The Tsezian (Tsezic, Didoic) languages form part of the Daghestanian branch of the Nakh-Daghestanian (East Caucasian) language family. They form one branch of an Avar-Andi-Tsez grouping within the family, the other branch of this grouping being Avar-Andi. Five Tsezian languages are conventionally recognized: Khwarshi (Avar x∑arßi, Khwarshi a¥’ilqo), Tsez (Avar, Tsez cez, also known by the Georgian name Dido), Hinuq (Avar, Hinuq hinuq), Bezhta (Avar beΩt’a, Bezhta beΩ¥’a. also known by the Georgian name Kapuch(i)), and Hunzib (Avar, Hunzib hunzib), although the Inkhokwari (Avar inxoq’∑ari, Khwarshi iqqo) dialect of Khwarshi and the Sagada (Avar sahada, Tsez so¥’o) dialect of Tsez are highly divergent. Tsez, Hinuq, Bezhta, and Hunzib are spoken primarily in the Tsunta district of western Daghestan, while Khwarshi is spoken primarily to the north in the adjacent Tsumada district, separated from the other Tsezian languages by high mountains. (See map 1.) In addition, speakers of Tsezian languages are also to be found as migrants to lowland Daghestan, occasionally in other parts of Russia and in Georgia. Estimates of the number of speakers are given by van den Berg (1995) as follows, for 1992: Tsez 14,000 (including 6,500 in the lowlands); Bezhta 7,000 (including 2,500 in the lowlands); Hunzib 2,000 (including 1,300 in the lowlands); Hinuq 500; Khwarshi 1,500 (including 600 in the lowlands). -

Syntax of Hungarian. Nouns and Noun Phrases, Volume 2

Comprehensive Grammar Resources Series editors: Henk van Riemsdijk, István Kenesei and Hans Broekhuis Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume 2 Edited by Gábor Alberti and Tibor Laczkó Syntax of Hungarian Nouns and Noun Phrases Volume II Comprehensive Grammar Resources With the rapid development of linguistic theory, the art of grammar writing has changed. Modern research on grammatical structures has tended to uncover many constructions, many in depth properties, many insights that are generally not found in the type of grammar books that are used in schools and in fields related to linguistics. The new factual and analytical body of knowledge that is being built up for many languages is, unfortunately, often buried in articles and books that concentrate on theoretical issues and are, therefore, not available in a systematized way. The Comprehensive Grammar Resources (CGR) series intends to make up for this lacuna by publishing extensive grammars that are solidly based on recent theoretical and empirical advances. They intend to present the facts as completely as possible and in a way that will “speak” to modern linguists but will also and increasingly become a new type of grammatical resource for the semi- and non- specialist. Such grammar works are, of necessity, quite voluminous. And compiling them is a huge task. Furthermore, no grammar can ever be complete. Instead new subdomains can always come under scientific scrutiny and lead to additional volumes. We therefore intend to build up these grammars incrementally, volume by volume. In view of the encyclopaedic nature of grammars, and in view of the size of the works, adequate search facilities must be provided in the form of good indices and extensive cross-referencing. -

Adjective Attribution (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 2)

Michael Rießler. 2016. Adjective attribution (Studies in Diversity Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog © 2016, Michael Rießler Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-944675-65-7 (Digital) 978-3-944675-66-4 (Hardcover) 978-3-944675-49-7 (Softcover) 978-1-530889-34-1 (Softcover US) ISSN: 2363-5568 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Felix Kopecky, Sebastian Nordhoff, Michael Rießler Proofreading: Martin Haspelmath, Joshua Wilbur Fonts: Linux Libertine, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Habelschwerdter Allee 45 14195 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Language Science Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. За най-любимите ми Алма, Ива и Кристина Contents Preface This is a thoroughly revised version of my doctoral dissertation Typology and evolution of adjective attribution marking in the languages of northern Eurasia, which I defended at Leipzig University in January 2011 and published electroni- cally as riesler2011a I am indebted to my family members, friends, project collab- orators, data consultants, listeners, supporters, sources of inspiration, opponents and other people who assisted in completing my dissertation. I am very thankful to the series editors who accepted my manuscript for pub- lication with this prestigious open-access publisher, to the technical staff at Lan- guage Science Press, as well as to proofreaders and other individuals who have spent their valuable time producing of this book. -

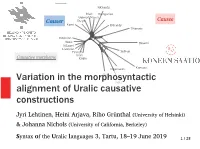

Variation in the Morphosyntactic Alignment of Uralic Causative

0.1 NKhanty Mari Hungarian Udmurt Mansi Causer Erzya Causee Komi EKhanty TNenets Estonian Votic SSaami NSaami Livonian Finnish Selkup Inari Causative morpheme Kildin Kamass Nganasan Variation in the morphosyntacticSEst Veps alignment of Uralic causative constructions Jyri Lehtinen, Heini Arjava, Riho Grünthal (University of Helsinki) & Johanna Nichols (University of California, Berkeley) Syntax of the Uralic languages 3, Tartu, 18–19 June 2019 1 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● Extension into the Uralic languages of the approach described in Nichols et al. (2004) – Lexical valence orientation: Transitivizing vs. detransitivizing (or causativizing vs. decausativizing) languages – In addition, phylogenetic models of Uralic language relationships – Phylogenies taking into account both valence orientation (grammar) and origin of relevant forms (etymology) 2 / 28 Causative alternation in Uralic ● 22 Uralic language varieties: – South Sámi, North Sámi, Inari Sámi, Kildin Sámi – Finnish, Veps, Votic, Estonian, Southern Estonian, Livonian – Erzya – Meadow Mari – Udmurt, Komi-Zyrian – Hungarian, Northern Mansi, Eastern Khanty, Northern Khanty – Tundra Nenets, Nganasan, Kamass, Selkup 3 / 28 Alternation in animate verbs ● For animate verbs, all surveyed languages are predominantly causativizing – e.g. ’eat’ / ’feed’: North Sámi borrat / borahit; Estonian sööma / söötma; Northern Mansi tēŋkwe / tittuŋkwe; Hungarian eszik / etet ● Little decaus., much caus.: North Sámi, S Estonian, Mari, Samoyed; much decaus., little caus.: Kildin Sámi, Livonian, -

Grammatical Case in Estonian

Grammatical Case in Estonian Merilin Miljan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences, University of Edinburgh September 2008 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is of my own composition, and that it contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree. The work reported in this thesis has been executed by myself, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Merilin Miljan ii Abstract The aim of this thesis is to show that standard approaches to grammatical case fail to provide an explanatory account of such cases in Estonian. In Estonian, grammatical cases form a complex system of semantic contrasts, with the case-marking on nouns alternating with each other in certain constructions, even though the apparent grammatical functions of the noun phrases themselves are not changed. This thesis demonstrates that such alternations, and the differences in interpretation which they induce, are context dependent. This means that the semantic contrasts which the alternating grammatical cases express are available in some linguistic contexts and not in others, being dependent, among other factors, on the semantics of the case- marked noun and the semantics of the verb it occurs with. Hence, traditional approaches which treat grammatical case as markers of syntactic dependencies and account for associated semantic interpretations by matching cases directly to semantics not only fall short in predicting the distribution of cases in Estonian but also result in over-analysis due to the static nature of the theories which the standard approach to case marking comprises. -

A Grammar of Chechen

A Grammar of Chechen Zura Dotton, Ph.D John Doyle Wagner 1 Background Information and Introduction 1.1 Speakers and Official Status Chechen is one of the co-official languages of the Republic of Chechnya, which is a federal subject of the Russian Federation. According to the most recent census data in 2010 there are approximately 1.4 million speakers of Chechen, making it one of the largest minority languages in the Russian Federation after Ukrainian and Tatar. Speakers of Chechen belong mostly to the Chechen ethnicity and are located primarily in Chechnya. Chechen is also spoken in countries with sizable Chechen minorities, namely Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Austria, Germany, Jordan, Turkey, Georgia, and urban centers in European Russia (particularly Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Rostov-na-Donu). 1.2 Distribution of Speakers Chechnya is located on the northern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains. The Republic of Chechnya is a subnational, semi-autonomous republic of the Russian Federation, and the independence of Chechnya has been at the center of the region’s history for much of the 20th and early 21st century. It shares political borders with the Republic of Ingushetia to the east, the Republic of Dagestan to the west, Stavropol Krai to the north, and an international border with the Republic of Georgia to the south. Outside of their ancestral homeland in the Caucasus, Chechen speakers are found in the Pankisi Gorge of neighboring Georgia and in the provinces of Tusheti and Kakheti. The Kisti and Chechen community in Georgia has grown dramatically in the recent decades due to the influx of refugees after the First and Second Chechen Wars as well as the replacement of the Ossetian community following the Georgian-Ossetian conflict in 2008. -

Pronouns and Adverbs, Figure and Ground: the Local Case Forms and Locative Forms of the Finnish Demonstratives in Spoken Discourse

of F inland. Pp. 65-92. sKY 1 996 Y earbook of the Linguistic As sociation Ritva LaurY Pronouns and adverbs, figure and ground: The local case forms and locative forms of the Finnish demonstratives in spoken discourse 1. Introduction Finnish has a large variety of forms available for speaking about where something is located. This is particularly so for the demonstratives, which have special locative forms in addition to case forms in the six local cases. The purpose of this papert is to examine the use of the local case forms and locative forms of the demonstratives in spoken Finnish in order to determine, first, what light the actual use of these forms may shed on the question of theii lexical category as either demonstrative pronouns or adverbs, and, secondly, how speakers make the choice between the different forms. 2. Data The data for the paper consist of ordinary conversations and and spoken nanatives recãrded in Finland between the late 1930s *i¿-tgqOr. The earlier narratives were recorded on disks and later transferred onto tapes; the later narratives were tape- recorded. There are altogether fifteen narratives from different dialectal areas; both eastern and westem dialects are represented. The eight conversations were tape-recorded between 1958 and -One 1991. of the conversations is from a pre-arranged meeting; all the rest are naturally occurring conversations between friends part of Ch.3 of (Laury 1995). 66 and family members. Some of the narratives were spontaneously produced in the course of conversation, while others were elicited (for further details conceming the data, see Laury 1995). -

A Grammar of Sanzhi Dargwa

A grammar of Sanzhi Dargwa Diana Forker language Languages of the Caucasus 2 science press Languages of the Caucasus Editors: Diana Forker (Universität Jena), Nina Dobrushina (National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow), Timur Maisak (Institute of Linguistics at the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow), Oleg Belyaev (Lomonosov Moscow State University). In this series: 1. Daniel, Michael, Nina Dobrushina & Dmitry Ganenkov (eds.). The Mehweb language: Essays on phonology, morphology and syntax. 2. Forker, Diana. A grammar of Sanzhi Dargwa. A grammar of Sanzhi Dargwa Diana Forker language science press Forker, Diana. 2020. A grammar of Sanzhi Dargwa (Languages of the Caucasus 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/250 © 2020, Diana Forker Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-196-2 (Digital) 978-3-96110-197-9 (Hardcover) DOI:10.5281/zenodo.3339225 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/250 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=250 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Diana Forker, Felix Anker, Felix Kopecky Proofreading: Ahmet Bilal Özdemir, Andrew Spencer, Aniefon Daniel, Daryl MacDonald, Felix Kopecky, Ivica Jeđud , Jeroen van de Weijer, Jezia Talavera, Laura Arnold, Laurentia Schreiber, Mykel Brinkerhoff, Jean Nitzke, Sebastian Nordhoff, Sune Gregersen, Tom Bossuyt, Alena Witzlack, Yvonne Treis Fonts: Libertinus, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Acknowledgments xi Spelling conventions xiii Glosses and other abbreviations xv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Sanzhi community and the Sanzhi language ............. -

Eastern Mansi (Konda) Grammar Ulla-Maija Forsberg

1 EASTERN MANSI (KONDA) GRAMMAR ULLA-MAIJA FORSBERG (English version of Ulla-Maija Kulonen: Itämansin kielioppi ja tekstejä, Société Finno-Ougrienne Helsinki 2007) CONTENTS Introduction I PHONOLOGY Consonants Consonant clusters Vowel systems Vowels in the initial syllables Quantity and vowel variation Vowels in the non-initial syllables II MORPHOPHONOLOGY Syllable structure Stem rakenne Monosyllabic stems Bisyllabic stems Stem variation Denasalization Suffix structure III MORPHOLOGY Noun declension Possessive suffixes Cases and their usage Nominative, dual and plural Accusative Lative Locatice Ablative Translative Instrumental Caritive / Abessive Adjective comparison and modal Pronoun declension Numerals Verb conjugation Tense Subject conjugation 2 Object conjugation and the usage Mood Imperative and optative Conditional Passive Verb nominal forms IV SYNTAX: STRUCTURES 3 INTRODUCTION This grammar of Eastern Mansi describes the Mansi dialects of Middle Konda and Lower Konda as they are manifested in the texts and grammar notes collected by Artturi Kannisto. This language form, exactly hundred years old at the time the present grammar was published in Finnish in 2007, was no more spoken as such at the offset of the 21st century. The data that this grammar is based on consists of the texts written in Middle Konda in the collection of samples Wogulische Volksdichtung by Artturi Kannisto and Matti Liimola. The materials have been previously published by the Finno-Ugrian Society in its series numbers 101 (WV I; mythological texts), 109 (WV II; heroic and war stories); 111 (WV III; fairy tales); 116 (WV V; songs from the great bear ceremonies) and 134 (WV VI; destiny songs and different kinds of small folklore genres).