Two Hampshire Airfields, Worthy Down and Chilbolton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazine & Conservatories 01264 359355 Andover & North Hampshire Gazette Your Free Local Community Magazine – Reaching Approx

your ISSUE No. 124 local DECEMBER 2017 Windows, Doors Magazine & Conservatories 01264 359355 Andover & North Hampshire Gazette Your free local community magazine – Reaching approx. 45,000 readers every month All Makes Servicing Restoration, Paintwork, Light Crash Repairs, Engine Re-builds T: 01264 772416 M: 07525 421104 THRUXTON CLASSIC RESTORATION [email protected] (Independent Jaguar Specialist) Unit 13 Mayfield Industrial Est, Weyhill, Nr Andover, SP11 8HU + Full installation of wood burning Visit our stoves and fireplaces new + Wood based heating systems HETAS- registered + Central heating upgrades showroom + All plumbing and heating works at Walworth + Member of National Association Business of Chimney Sweeps Park 01264 310493 www.humphreyandcrockett.co.uk [email protected] Unit 11, Focus 303 Business Centre, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 5NY Online Advertising from as little as £10 per month Bespoke steelwork and ornamental fabrications – including For details contact Tracey on Balconies . Gates . Railings Tel: 01264-316499 Staircases . Balustrades . Garden Features Mob: 07775-927161 Obelisks from just £25 email: [email protected] Plant Support Hoops from £10 per pair Tulip and Narcissi Baskets £35 Plant Supports from just £8.50 per pair Hanging Basket Brackets from £8.50 Fire Pits from £50 Please contact us for your free We invite you to our Advent social with our exhibition of quilts made by our students no obligation quotation 16th, 19th and 20th December 2017 – SALE 30% on selected items. Our last working day this year will be Tel: 01264 737 747 22st Dec, we will re-open 3rd Jan 2018. Merry Christmas and happy New Year Web: www.boaengineering.co.uk to all our customers. -

De Havilland Technical School, Salisbury Hall .46 W

Last updated 1 July 2021 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| DeHAVILLAND DH.98 MOSQUITO ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 98001 • Mk. I W4050 (prototype E-0234): built Salisbury Hall, ff Hatfield 25.11.40 De Havilland Technical School, Salisbury Hall .46 W. J. S. Baird, Hatfield .46/59 (stored Hatfield, later Panshanger, Hatfield, Chester, Hatfield: moved to Salisbury Hall 9.58) Mosquito Aircraft Museum/ De Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, Salisbury Hall, London Colney 5.59/20 (complete static rest. 01/03, remained on display, one Merlin rest. to running condition) _______________________________________________________________________________________ - PR Mk. IV DK310 forced landing due engine trouble, Berne-Belpmoos, Switzerland: interned 24.8.43 (to Swiss Army as E-42) HB-IMO Swissair AG: pilot training 1.1.45 (to Swiss AF as B-4) 7.8.45/53 wfu 9.4.53, scrapped 4.12.53 _______________________________________________________________________________________ - PR Mk. IV DZ411 G-AGFV British Overseas Airways Corp, Leuchars 12.42/45 forced landing due Fw190 attack, Stockholm 23.4.43 dam. take-off, Stockholm-Bromma 4.7.44 (returned to RAF as DZ411) 6.1.45 _______________________________________________________________________________________ -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

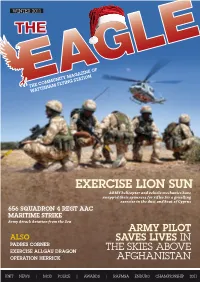

Exercise Lion

WINTER 2011 Station ying THE COMMUNITY MAGAZINE OF WATTISHAM FL EXERcise Lion sun ARMY helicopter and vehicle mechanics have swapped their spanners for rifles for a gruelling exercise in the dust and heat of Cyprus 656 SQuaDRon 4 Regt aac MARitime stRIKE Army Attack Aviation from the Sea ARmy piLot ALso saVes LIVes in PADRes coRneR EXERcise ALLgau DRagon the SKieS ABOVE OpeRation HERRicK AfGHAniSTAN Unit NewS | MOD POLICE | AWArdS | RAFMSA ENDURO CHAMPIONSHIP 2011 THE EAGle CONTENTS THE EAGle CONTENTS 3 2 From the Editor: Lt Col (Retd) RW SILK MBE Station Staff Officer elcome to the winter (Christmas) edition of The Eagle, which again covers operations, W training and a host of other activities back at Wattisham, our Home Base. You will see from the Station 2 Commander’s introduction that the past few months have been somewhat hectic with all kinds of activities, which has pushed the station very much into the media spotlight. Of course on the downside the Station Commander, Col Neale Moss, is preparing to leave us to be replaced by Col Andy Cash in the New Year. I will not dwell on this at the moment as the various reports of the ‘Governor’’ leaving will be carried in the next edition. Finally, the editorial team wishes all our readers a peaceful Christmas and the very best of fortune in the New Year. 30 06 I Foreword 26 I 7 Air Assault Battalion REME 36 I Welfare Matters Introduction by Colonel Neale Moss News and updates from 7 Air Assault News and updates from the various Unit OBE, AH Force Commander, Wattisham Battalion REME, including Exercises Lion Welfare Offices. -

Aircraft Slide Collection Dates

MS-402: Aircraft Slide Collection Collection Number: MS-402 Title: Aircraft Slide Collection Dates: 1970-1998 Creator: Wayne and Karen Pittman Summary/Abstract: The Aircraft Slide Collection is an assortment of 35mm color slides of aircraft in numerous operational locations, as well as air museums, static displays, and air shows. Quantity/Physical Description: 1 linear foot (3 flat storage three-ring binder boxes) Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections and Archives, Paul Laurence Dunbar Library, Wright State University, Dayton, OH 45435-001, (937) 775-2092 Restrictions on Access: There are no restrictions on accessing material in this collection. Restrictions on Use: Copyright restrictions may apply. Unpublished manuscripts are protected by copyright. Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder. Preferred Citation: (Box Number, Folder Number), MS-402, Aircraft Slide Collection, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio Acquisition: The Aircraft Slide Collection was donated to Wright State University Special Collections and Archives in September 2008. Revisions: Revised by Jeremy Katz (February 2011) Processed by: Ryan Qualls Arrangement: The collection is arranged into three series and four subseries: Series I: Air Shows and Aero Teams Subseries 1A: Air Shows Subseries 1B: Aero Teams 1 Series II: Museums and Static Displays Subseries IIA: United States Subseries IIB: Foreign Series III: Gate Guards and Individual Aircraft Biographical/Historical Note: The Aircraft Slide Collection was compiled by Wayne and Karen Pittman during their travels to various air shows and museums throughout the North America and Europe. Scope and Content: The Aircraft Slide Collection is an assortment of color slides produced by Wayne and Karen Pittman on their travels to various air shows and museums around North America and Europe. -

69 R00002 WH804 Eeco Canberra PR.7 17 Sqn "Z" 69D R00003 WH

R00001 WH703 EECo Canberra B.2 5 Sqn "U" 69 R00002 WH804 EECo Canberra PR.7 17 Sqn "Z" 69D R00003 WH952 EECo Canberra B.6 RAE 69D R00004 WJ610 EECo Canberra T.19 85 Sqn "T" 69 R00005 WJ620 EECo Canberra B.15 90 Signals Group 69 R00006 WK164 EECo Canberra B.2 A&AEE Naval Test Sqn 69 R00007 WT327 EECo Canberra B(I).6 RRE 71 R00008 XM271 EECo Canberra B(I).8 16 Sqn (grainy) 71 R00009 WH952 EECo Canberra B.6 RAE 73 R00010 WE192 EECo Canberra PR.3 231 OCU 72 R00011 WT483 EECo Canberra T.4 231 OCU 72 R00012 WT482 EECo Canberra T.4 231 OCU "C" 72 R00013 WT480 EECo Canberra T.4 231 OCU "B" 73 R00014 XP743 EECo Lightning F.3 29 Sqn"B" wfu Leconfield R00015 WJ610 EECo Canberra T.19 85 Sqn "T" 71D R00016 WH724 EECo Canberra T.19 100 Sqn "O" 72 R00017 XM279 EECo Canberra B(I).8 3 Sqn "L" 71 R00018 XM263 EECo Canberra B(I).8 16 Sqn 71 R00019 WL744 Avro Shackleton MR.2 Ballykelly dump 68 R00020 VZ608 Gloster Meteor PR.9 Newark Air Museum 73D R00021 WM292 Gloster Meteor TT.20 FAA Museum "841" 78D R00022 WA669 Gloster Meteor T.7 CFS 73 R00023 WH286 Gloster Meteor F.8 229 OCU "A" 70D R00024 WA991 Gloster Meteor U.16 RAE Llanbedr "F" 73 R00025 WD702 Gloster Meteor TT.20 Valley dump "U" 73 R00026 WA669 Gloster Meteor T.7 72 R00027 WM223 Gloster Meteor TT.20 3 CAACU "W" grainy 67 R00028 WD646 Gloster Meteor TT.20 3 CAACU "R" grainy 67 R00029 WS777 Gloster Meteor NF.14 displayed Buchan 85 Sqn 67 R00030 VZ567 Gloster Meteor F.8 229 OCU D R00031 WH291 Gloster Meteor F.8 229 OCU 79 Sqn 73 R00032 WF417 Vickers Varsity T.1 BLEU 65 R00033 WP859 DHC1 Chipmunk T.10 -

Planes Trains & Autos

Premium Small Group Tour departing 27th June 2018 A leisurely paced, small group 23-day tour, escorted from NZ by aviation enthusiasts Kevin & Melanie Salisbury. Featuring Singapore Air Force Museum, Kelvedon Nuclear Bunker, Shuttleworth Collection & Air Display RAF Wyton - Pathfinder Collection, Lincs Aviation Heritage Centre, Bletchley Park International Bomber Command Centre, Battle of Britain Memorial Flight Visitors Centre Newark Air Museum, RAF Scampton, Yorkshire Air Museum, Avro Heritage Museum RAF Cosford, SS Great Britain, Royal International Air Tattoo, Flying Legends & Imperial War Museum Mosquito Museum, The Bunker – Uxbridge, Castle Bromwich Jaguar Factory Bedford – Woodhall Spa – Lincoln – York – Castle Bromwich – Cheltenham - Cambridge Highlighting Let us take you on an amazing journey to some of the best-known museums and events in the UK Melanie Salisbury Travel Managers 12 Furl Close Pyes Pa Tauranga 3112 021 076 8308 www.aviationtoursnz.com Registered office – Level 7, 2 Emily Place, Auckland Tour Itinerary – Bomber County 100 Day 1 – Wednesday 27th June In flight (L& D in flight) Meet and greet at Auckland airport at 10.30am. We depart on Singapore Air SQ286 at 12.10 pm, and arrive in Singapore at 7pm. We will be transferred to our hotel for our overnight stay. 1 night Singapore Day 2 – Thursday 28th June Singapore Air Force Museum (B, D) Spend your day at leisure or join us for a morning visit to the Air Force Museum with the afternoon at leisure. We have a late check out at 6pm, will have dinner together, and then transfer to the airport for our overnight flight to London departing 11.30pm. -

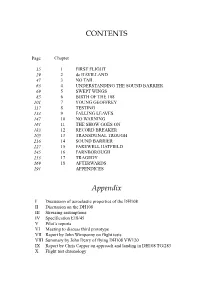

Sound Barrier Indexedmaster.Indd

9 CONTENTS Page Chapter 15 1 FIRST FLIGHT 29 2 de HAVILLAND 47 3 NO TAIL 63 4 UNDERSTANDING THE SOUND BARRIER 69 5 SWEPT WINGS 85 6 BIRTH OF THE 108 101 7 YOUNG GEOFFREY 117 8 TESTING 133 9 FALLING LEAVES 147 10 NO WARNING 161 11 THE SHOW GOES ON 183 12 RECORD BREAKER 205 13 TRANSDUNAL TROUGH 216 14 SOUND BARRIER 227 15 FAREWELL HATFIELD 245 16 FARNBOROUGH 253 17 TRAGEDY 269 18 AFTERWARDS 291 APPENDICES Appendix I Discussion of aeroelastic properties of the DH108 II Discussion on the DH108 III Stressing assumptions IV Specification E18/45 V Pilot’s reports VI Meeting to discuss third prototype VII Report by John Wimpenny on flight tests VIII Summary by John Derry of flying DH108 VW120 IX Report by Chris Capper on approach and landing in DH108 TG/283 X Flight test chronology 10 11 INTRODUCTION It was an exciting day for schoolboy Robin Brettle, and the highlight of a project he was doing on test flying: he had been granted an interview with John Cunningham. Accompanied by his father, Ray, Robin knocked on the door of Canley, Cunningham’s home at Harpenden in Hertfordshire and, after the usual pleasantries were exchanged, Ray set up the tape recorder and Robin began his interview. He asked the kind of questions a schoolboy might be expected to ask, and his father helped out with a few more specific queries. As the interview drew to a close, Robin plucked up courage to ask a more personal question: ‘Were you ever scared when flying?’ Thinking that Cunningham would recall some life-or-death moments when under fire from enemy aircraft during nightfighting operations, father and son were very surprised at the immediate and direct answer: ‘Yes, every time I flew the DH108.’ Cunningham, always calm, resolute and courageous in his years as chief test pilot of de Havilland, was rarely one to display his emotions, but where this aircraft was concerned he had very strong feelings, and there were times during the 160 or so flights he made in the DH108 that he feared for his life - and on one occasion came close to losing it. -

Andover Business Park - Public Art Commission Call for Expressions of Interest

Project Brief: TVPA001 ANDOVER BUSINESS PARK - PUBLIC ART COMMISSION CALL FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST ‘FLIGHT AND NAVIGATION’ ARTIST BRIEF VISION TVBC in partnership with Goodman wish to commission a work of public art for the new Andover Business Park. It is envisaged that this piece will provide a landmark for the site, marking the entrance to Andover, and will make reference to the history of the site as Andover Airfield. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES To commission a work of art that will celebrate the regeneration of Andover Business Park whilst encapsulating the history of the site as RAF Andover. To produce an artwork of sufficient scale and impact to create a landmark that appeals to a broad audience and inspires comment beyond its immediate locality. to engage with users of the site and other communities living close to the site BACKGROUND Andover Business Park has a rich history as RAF Andover. In the early twentieth century it was known as ‘No. 2 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping’. Several experimental military aircraft made their first flights from the airfield. Amongst them were: the Westland Yeovil; the Westland Witch; the Westland F.7/30; and all of the Westland-Hill Pterodactyl series of experimental flying wing aircraft. RAF Andover has a unique place in British history, as the first British military unit to be equipped with helicopters. The Helicopter Training School, was formed in January 1945 at RAF Andover. Post-war, RAF Andover continued to be used for helicopter flying training and operational research. The station's association with aviation research continued, and some of the trials of experimental vertical take-off aircraft took place on the station, including some of the trials for the Hawker Siddeley Andover which was named after the station. -

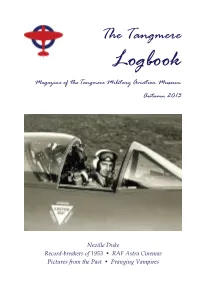

The Tangmere

The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2013 Neville Duke Record-breakers of 1953 • RAF Astra Cinemas Pictures from the Past • Pranging Vampires Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Trust Company Patron: The Duke of Richmond and Gordon Hon. President: Duncan Simpson, OBE Hon. Life Vice-President: Alan Bower Council of Trustees Chairman: Group Captain David Baron, OBE David Burleigh, MBE Reginald Byron David Coxon Dudley Hooley Ken Shepherd Phil Stokes Joyce Warren Officers of the Company Hon. Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Hon. Secretary: Joyce Warren Management Team Director: Dudley Hooley Curator: David Coxon General Manager and Chief Engineer: Phil Stokes Events Manager: David Burleigh, MBE Publicity Manager: Cherry Greveson Staffing Manager: Mike Wieland Treasurer: Ken Shepherd Shop Manager: Sheila Shepherd Registered in England and Wales as a Charity Charity Commission Registration Number 299327 Registered Office: Tangmere, near Chichester, West Sussex PO20 2ES, England Telephone: 01243 790090 Fax: 01243 789490 Website: www.tangmere-museum.org.uk E-mail: [email protected] 2 The Tangmere Logbook The Tangmere Logbook Magazine of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Autumn 2013 The Record-breakers of 1953 4 Four World Air Speed Records are set in a remarkably busy year David Coxon Neville Duke as I Remember Him 8 An acquaintance with our late President David Baron Adventures of an RAF Cinema Projectionist 11 Chance encounters with Astra cinemas at home and abroad, and one with Ava Gardner Phil Dansie Pictures from My Father’s Album 19 . of some interesting historical moments Stan Hayter Operation Beef 23 How to provoke official displeasure by pranging yet another pampered Vampire Eric Mold From Our Archives . -

Raf Squadron

I am able to show you in this magazine all of our current RAF stock from all of the popular series. Some quantities are low, so do not delay! Also, if there are any covers not featured, please feel free to contact us and let us know. THE ROYAL We are always happy to take on the challenge of acquiring your missing covers for you. AIR FORCE Happy Browsing & Best Wishes June 2019 Issue 9 RFDC Covers RFDC72 £7.50 1989 Anniversaries - 30th Anniversary of RAFLET. RAF Bomber Series RAFC014 £15 1993 Autumn - 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain. RAF Museum RAFSC01 £15 RAFB01C £125 £25 per month for 5 months 7th September 1981 Sopwith Tabloid special signed cover by Arthur Bomber’ Harris. 1970 RAF Upavon - Farnborough WWII 50th Anniversary Operation Judgement Battle of Britain 1940 22nd - 31st July RAFA03S £15 Signed Wing Commander George Unwin 01303 278137 JS40/07S £20 Major O Patch & Capt.AWF Sutton EMAIL: [email protected] LOVE COVERS? JOIN THE CLUB and SAVE! Members of our Unsigned Collectors Club save £1 on the cost of each new cover. There’s no obligation to buy but your covers will be reserved for you so you’ll never miss out! Why not join today? Visit our website at www.buckinghamcovers.com/clubs for details Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] RFDC COVERS RFDC1 £4.50 RFDC2 £4.50 RFDC3 £7.50 RFDC4 £7 1981 Folklore. The 1981 Disabled. RAF Medical 1981 Butterflies - Lepidoptera. 1981 National Trust - Hendon Ghost. -

Brooklands Aerodrome & Motor

BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY (June 2017) Radley House Partnership BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS CONTENTS Aerodrome Road 2 The 1907 BARC Clubhouse 8 Bellman Hangar 22 The Brooklands Memorial (1957) 33 Brooklands Motoring History 36 Byfleet Banking 41 The Campbell Road Circuit (1937) 46 Extreme Weather 50 The Finishing Straight 54 Fuel Facilities 65 Members’ Hill, Test Hill & Restaurant Buildings 69 Members’ Hill Grandstands 77 The Railway Straight Hangar 79 The Stratosphere Chamber & Supersonic Wind Tunnel 82 Vickers Aviation Ltd 86 Cover Photographs: Aerial photographs over Brooklands (16 July 2014) © reproduced courtesy of Ian Haskell Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY Radley House Partnership Timelines: June 2017 Page 1 of 93 ‘AERODROME ROAD’ AT BROOKLANDS, SURREY 1904: Britain’s first tarmacadam road constructed (location?) – recorded by TRL Ltd’s Library (ref. Francis, 2001/2). June 1907: Brooklands Motor Circuit completed for Hugh & Ethel Locke King and first opened; construction work included diverting the River Wey in two places. Although the secondary use of the site as an aerodrome was not yet anticipated, the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club soon encouraged flying there by offering a £2,500 prize for the first powered flight around the Circuit by the end of 1907! February 1908: Colonel Lindsay Lloyd (Brooklands’ new Clerk of the Course) elected a member of the Aero Club of Great Britain. 29/06/1908: First known air photos of Brooklands taken from a hot air balloon – no sign of any existing route along the future Aerodrome Road (A/R) and the River Wey still meandered across the road’s future path although a footbridge(?) carried a rough track to Hollicks Farm (ref.