Sound Barrier Indexedmaster.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People and Planes: Technical Versus Social Narratives in Aviation Museums

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Museums Scotland Research Repository Brown, Ian (2018) People and Planes: Technical versus social narratives in aviation museums. Journal of Aeronautical History, 2018 (07). pp. 200-207. http://repository.nms.ac.uk/2121 Deposited on: 17 September 2018 NMS Repository – Research publications by staff of the National Museums Scotland http://repository.nms.ac.uk/ Journal of Aeronautical History Paper 2018/07 People and Planes: Technical versus social narratives in aviation museums Ian Brown Assistant Curator of Aviation, National Museums Scotland Abstract Redevelopment of two Second World War hangars at the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian provided an opportunity to re-interpret the museum collections. This short account of the project looks at the integrated incorporation of oral history recordings. In particular, it looks at the new approach taken to the interpretation of the museum’s Messerschmitt Me 163B-1a Komet rocket fighter. This uses oral histories from the only Allied pilot to make a powered flight in a Komet, and from a Jewish slave labourer who was forced to build aircraft for Nazi Germany. This focus on oral history, along with an approach to interpretation that emphasises social history, rather than technology, has proven popular with visitors and allowed the building of audiences. 1. INTRODUCTION Traditionally, transport museums and collections have focused on the technological history of their objects, producing Top Trump displays which look at the fastest, biggest, most mass-produced, etc. Colin Divall and Andrew Scott noted in 2001 that ‘transport museums followed some way behind other sorts of museums in dealing with social context.’ 1 These displays often include great detail about the engines and their performance, sometimes including extreme technical detail such as bore size, stroke length, etc. -

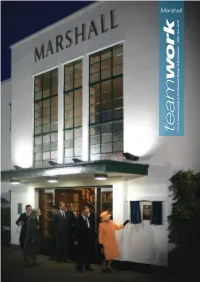

TEAMWORK Re-Design

M a r s h team wo rk a The in-house journal of the Marshall Group of Companies New Year 2010 l l Chairman’s comments Awards, followed by our Long Service members of staff on the payroll on that date. Awards, and then by a very special Dinner On 5th November we sponsored the for the 25 families which had each achieved Marshall of Cambridge Centenary Fireworks over 100 years of service, an enormous on Midsummer Common in Cambridge, achievement of which we are hugely proud. attended by the Mayor of Cambridge and many other dignitaries and Cambridge Next came a charity dinner attended by families, some of whom wrote in to me and over 700 of our business partners, to the local paper saying they were the best suppliers and customers which, following a Cambridge fireworks ever. really kind and personal video message from His Royal Highness the Prince of The real icing on the cake came on I write this with 2009 coming to a Wales, entertainment was provided by November 19th when we received the very close and would like to share with Jamie Cullum and Kit and the Widow. rare honour of a special centennial visit to you the huge pride which I feel £140,000 was raised for the Prince’s Trust our business by Her Majesty the Queen personally, and for all of us in our which will enable budding entrepreneurs to accompanied by His Royal Highness The Group, on the resounding triumph of be given the opportunity similar to that Duke of Edinburgh, who both met a number given to my grandfather 100 years ago. -

The De Havilland Aeronautical Technical School Association PYLON MAGAZINE

The de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School Association PYLON MAGAZINE The de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School published a periodic magazine, Pylon, from 1933 to 1970, with gaps at times especially during WW2. A partial set is held by the de Havilland Aircraft Museum. The de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School Association (DHAeTSA) has published nine issues in recent years, five of which were to commemorate successive five-year anniversaries of the founding of the School in 1928. Pylon 70 (1998) commemorated the 70th anniversary. It was a compilation of items from past Pylons, chosen by Bruce Bosher and Ken Fulton, with the digital work done by Ken’s daughter Carol. It was in A5 format. Pylon 75 (2003) commemorated the 75th anniversary. This was an all-new collection of contributions from members, collated by Bruce Bosher and Ken Watkins, who created the computer file. It was in A4 format, as have been all subsequent issues. Pylon 2005. With much material available, an intermediate issue was published at Christmas 2005, master-minded by Ken Watkins. Pylon 80 (2008) commemorated the 80th anniversary and again was master-minded by Ken Watkins. Pylon 2011. Another intermediate issue was published in October 2011, compiled by a new team led by Roger Coasby. Pylon 85 (2013) commemorated the 85th anniversary and was compiled by the same team. Pylon 2015. An intermediate issue was published in October 2015, again by the same team. Pylon 90, commemorating the 90th anniversary, was published in June 2018 by the Coasby team. It was the largest issue ever. Pylon 2020 was published in September 2020 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the de Havilland Aircraft Company Ltd on 25th September 1920. -

Minister's Letter

L e a f l e t Greenbank Parish Church Minister’s Letter Braidburn Terrace, EH10 6ES No 643 May 2015 Dear Friends Pulpit Diary A couple of weeks ago early church? Or was Je- the BBC showed a tel- sus pointing to himself May 3 evision programme as the rock? Or perhaps 9.30am First Sunday Service led by called “In the footsteps it was Peter’s faith in him World Mission of St Peter”. It was a re- that was the rock? At first 10.30am Morning Worship peat of a two–part doc- glance this looks like a umentary, filmed in the multiple choice question Holy Land and present- in an exam paper. May 10 ed by the actor David But we will never know 10.30am Morning Worship Suchet. I don’t remem- in which direction Jesus ber seeing it before. And was looking or point- May 17 this time round I only ing when he spoke these saw the first part, which words. And it could be 10.30am Morning Worship took you through the that Jesus or even the life of the apostle Simon Gospel writer was us- May 24 Peter from his early days until the death ing a piece of inspired word-play here and of Jesus. I would have liked to see the sec- more than one of the above options was 9.30 Pentecost Communion ond part of the programme which charts intended. This question, like many others 10.30am Morning Worship for Pentecost the transformation of Peter from impetu- that arise as we explore the Christian faith, ous, bewildered and grieving disciple into cannot be treated like a multiple choice May 31 respected leader of the early Church, and question in an exam paper. -

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE a Need for Speed

n HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE A need for speed Mach 0.8 to 1.2 and above the speed of powerful turbine engine available. To mit- Skystreak taught lots sound, respectively). The U.S. Army Air igate as much risk as possible, the team Forces took responsibility for supersonic kept the design simple, using a conven- about flight near research—which resulted in Chuck Yea- tional straight wing rather than the new ger breaking the sound barrier in the Bell and mostly unproven swept wing. The the sound barrier X-1 on Oct. 14, 1947. That historic event 5,000-lb.-thrust (22-kilonewton) Allison overshadowed the highly successful re- J35-A-11 engine filled the fuselage, leav- BY MICHAEL LOmbARDI search conducted by the pilots who flew ing just enough room to house instrumen- s World War II was coming to a the Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak to the edge tation and a pilot in a cramped cockpit. close, advances in high-speed aero- of the sound barrier while capturing new Because of the lack of knowledge about Adynamics were rapidly progressing world speed records. the survivability of a high-altitude, high- beyond the ability of the wind tunnels of The D-558-1 was developed by the speed bailout, Douglas engineers designed the day, prompting a dramatic expansion Douglas Aircraft Company, today a part a jettisonable nose section that could pro- of flight-test research and experimental of Boeing, at its El Segundo (Calif.) tect the pilot until a safe bailout speed was aircraft. Division. It was designed by a team led reached. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Airspace: Seeing Sound Grades

National Aeronautics and Space Administration GRADES K-8 Seeing Sound airspace Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Museum in a BO SerieXs www.nasa.gov MUSEUM IN A BOX Materials: Seeing Sound In the Box Lesson Overview PVC pipe coupling Large balloon In this lesson, students will use a beam of laser light Duct tape to display a waveform against a flat surface. In doing Super Glue so, they will effectively“see” sound and gain a better understanding of how different frequencies create Mirror squares different sounds. Laser pointer Tripod Tuning fork Objectives Tuning fork activator Students will: 1. Observe the vibrations necessary to create sound. Provided by User Scissors GRADES K-8 Time Requirements: 30 minutes airspace 2 Background The Science of Sound Sound is something most of us take for granted and rarely do we consider the physics involved. It can come from many sources – a voice, machinery, musical instruments, computers – but all are transmitted the same way; through vibration. In the most basic sense, when a sound is created it causes the molecule nearest the source to vibrate. As this molecule is touching another molecule it causes that molecule to vibrate too. This continues, from molecule to molecule, passing the energy on as it goes. This is also why at a rock concert, or even being near a car with a large subwoofer, you can feel the bass notes vibrating inside you. The molecules of your body are vibrating, allowing you to physically feel the music. MUSEUM IN A BOX As with any energy transfer, each time a molecule vibrates or causes another molecule to vibrate, a little energy is lost along the way, which is why sound gets quieter with distance (Fig 1.) and why louder sounds, which cause the molecules to vibrate more, travel farther. -

Meet the Fighters Flying Display Schedule Sunday 11 September 2016

The Duxford Air Show: Meet The Fighters Flying Display Schedule Sunday 11 September 2016 1.30pm Last of the Piston Fighters Grumman F8F Bearcat The Fighter Collection Hawker Fury FB 11 Air Leasing Fighter Trainers North American Harvard IV Aircraft Restoration Company de Havilland DHC-1 Chipmunk Aircraft Restoration Company de Havilland DHC-1 Chipmunk M. Jack First World War Fighters Bristol F2B Fighter Shuttleworth Collection Sopwith Snipe WWI Aviation Heritage Trust 109 Pair Hispano Buchón (Messerschmitt Bf 109) Spitfire Ltd Hispano Buchón (Messerschmitt Bf 109) Historic Flying Ltd Dunkirk Trio Hispano Buchón (Messerschmitt Bf 109) Historic Flying Ltd Supermarine Spitfire Mk Ia - AR213 Comanche Fighters Supermarine Spitfire Mk Ia - X4650 Historic Flying Ltd 1930’s Biplane Fighters Gloster Gladiator Mk II The Fighter Collection Hawker Nimrod Mk I The Fighter Collection Hawker Nimrod Mk II Historic Aircraft Collection Hawker Fury Mk I Historic Aircraft Collection Hawker Demon H. Davies 2.30pm Battle of Britain Memorial Flight Avro Lancaster B1 Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, RAF Coningsby Great War Fighters Royal Aircraft Factory SE5a x 3 Great War Display Team Fokker DR.1 Triplane x 2 Great War Display Team Sopwith Triplane Great War Display Team Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c Great War Display Team Junkers CL1 x 2 Great War Display Team 2.55pm - 3.10pm Intermission Continued overleaf 3.10pm Second World War Fighters Yakovlev Yak-3 M. Davy Goodyear FG-1D Corsair The Fighter Collection Fighter Gunnery Training Piper Cub & Drogue Skytricks -

North Weald the North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4

The Spirit of North Weald The North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 4 North Weald’s role during World War 2 Epping Forest District Council www.eppingforestdc.gov.uk North Weald Airfield Hawker Hurricane P2970 was flown by Geoffrey Page of 56 Squadron when he Airfield North Weald Museum was shot down into the Channel and badly burned on 12 August 1940. It was named ‘Little Willie’ and had a hand making a ‘V’ sign below the cockpit North Weald Airfield North Weald Museum North Weald at Badly damaged 151 Squadron Hurricane war 1939-45 A multinational effort led to the ultimate victory... On the day war was declared – 3 September 1939 – North Weald had two Hurricane squadrons on its strength. These were 56 and 151 Squadrons, 17 Squadron having departed for Debden the day before. They were joined by 604 (County of Middlesex) Squadron’s Blenheim IF twin engined fighters groundcrew) occurred during the four month period from which flew in from RAF Hendon to take up their war station. July to October 1940. North Weald was bombed four times On 6 September tragedy struck when what was thought and suffered heavy damage, with houses in the village being destroyed as well. The Station Operations Record Book for the end of October 1940 where the last entry at the bottom of the page starts to describe the surprise attack on the to be a raid was picked up by the local radar station at Airfield by a formation of Messerschmitt Bf109s, which resulted in one pilot, four ground crew and a civilian being killed Canewdon. -

The Mathematical Approach to the Sonic Barrier1

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 6, Number 2, March 1982 THE MATHEMATICAL APPROACH TO THE SONIC BARRIER1 BY CATHLEEN SYNGE MORAWETZ 1. Introduction. For my topic today I have chosen a subject connecting mathematics and aeronautical engineering. The histories of these two subjects are close. It might however appear to the layman that, back in the time of the first powered flight in 1903, aeronautical engineering had little to do with mathematics. The Wright brothers, despite the fact that they had no university education were well read and learned their art using wind tunnels but it is unlikely that they knew that airfoil theory was connected to the Riemann conformai mapping theorem. But it was also the time of Joukowski and later Prandtl who developed and understood that connection and put mathematics solidly behind the new engineering. Since that time each new generation has discovered new problems that are at the forefront of both fields. One such problem is flight near the speed of sound. This one in fact has puzzled more than one generation. Everyone knows that in popular parlance an aircraft has "crashed the sonic *or sound barrier" if it flies faster than sound travels; that is, if the speed of the craft q exceeds the speed of sound c or the Mach number, M = q/c > 1. In simple, if perhaps too graphic, terms this means that if you are in the line of flight the plane hits you before you hear it. But it is not my purpose to talk about flight at the speed of sound. -

CAPT ERIC BROWN 21 January 1919-21 February 2016

ERIC ‘WINKLE’ BROWN CAPT ERIC BROWN 21 January 1919-21 February 2016 WORDS: NICHOLASJONES 28 www.aeroplanemonthly.comAEROPLANE APRIL2016 n17September 1939, the the 487 different types of aircraft flown. Most surprisingly of all, when we captain of HMS Courageous Butitwas during themany relaxed discussed hismeeting with Himmler, orderedthat his boat be mealswesharedin-between the filming Eric went into some detail as to what turnedinto windsoits days thatIbegan to learn moreabout followed, oncehis question about aircraftO could take off.Unknowingly, the man behind the records. These the arrest of Wernher vonBraun had he puthimself across thebow of U29, lunches quickly established apattern. unmasked the SS monster.Did Eric lurking nearbyunder the Irish Sea. The Thevenue was usually theRAF Club’s thereforeknowwhere Himmlerwas U-boat captainseizedthe moment. Running Horse Tavern, the best-value buried?“Yes!”, he replied —but this Twenty minutes later, Courageous pub in London. Eric habitually ordered wasone detail he would not divulge. hadsunk, leaving the Fleet Air Arm aSpanish omelette while Ihad the Onemight getpeopleknocking on the desperately shortofpilots. scampi, having wondered beforehand door,askingfor directions to thegrave Afew days latera20-year-old RAF which further astonishing stories he —and Eric always kept his address and officer saw anotice inviting pilotsto woulddivulge. telephone number in his‘Who’s Who’ transfertothe FAAtomake up its And he neverfailedtodivulge, forhis entry. shortfall.Champing at thebit for some memory was alwaysoutstanding. Once, That was so typically Eric. Therewas action during the tedium of the ‘phoney while lamenting the terrible news from atimewhen many famouspeople still war’,hevolunteered. Thus began the Syria that played on the bar’s television had theirnumbers in the telephone naval flying career of Capt Eric Melrose that day,hesuddenlytold me howhe book. -

DENHAMS Antique Sale 697 to Be Held on 03Rd August of 2016

DENHAMS Antique sale 697 to be held on 03rd August of 2016 INDEX AND ORDER OF SALE START LOT European and Oriental Ceramic and Glassware 1 Sale starts at 10am Items from the Estate of Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown' 151 Not before 11.15am Metalware, Collectors Items, Ephemera, Carpets, Fabrics, Toys, Curios etc 178 Not before 11.30am Oil Painting, Watercolours and Prints 417 Not before 1pm Silver, Silver Plated items, Jewellery & Objects of Virtue 497 Not before 1.30pm Clocks and Scientific Instruments 796 Not before 3.15pm Rugs and Carpets 825 Not before 3.30pm Antique and Fine Quality Furniture 857 Not before 3.30pm PUBLIC VIEWING Friday 29th July 9am - 5pm Saturday 30th July 9am - 12 noon Monday 1st August 9am - 5.30pm Tuesday 2nd August 9am - 7pm Wednesday 3rd August 9am - 10am IMPORTANT NOTICES PHONE BIDS Limited telephone bidding is available for Antique auctions, please ensure lines are booked by no later than 5pm Tuesday, prior to the Auction. BIDDING Prior to bidding you will be required to register for a Paddle Number, two forms of identity with proof of address and a home telephone number will be required. COMMISSION Buyers Premium of 15% plus vat (18% inclusive) is payable on the hammer price of every lot. PAYMENT Payment is welcome by debit and credit card. (there is a 3.5% surcharge on invoices for credit cards). Payment by cheque is not accepted. CLEARING Clearing of SMALL items is allowed during the auction for a £1 per lot 'fine' that is donated to charity DELIVERY For delivery of furniture we recommend Libbys Transport 01306 886755 or mobile 07831 799319 Page 1/51 European and Oriental Ceramic and Glassware IMPORTANT - All lots are sold as seen.