Pdf | 822.69 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Assessment of the Implementation of Alternative Process Technologies for Rural Heat and Power Production from Cocoa Pod Husks

Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Master of Science Thesis KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management Department of Energy Technology Division of Heat and Power Technology SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM Master of Science Thesis EGI 2016: 034 MSC EKV1137 Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Approved Examiner Supervisors Reza Fakhraie Reza Fakhraie (KTH) David Bauner (Renetech AB) Commissioner Contact person ii Abstract Cocoa pod husks are generated in Côte d’Ivoire, in abundant quantities annually. The majority is left as waste to decompose at the plantations. A review of the ultimate and proximate composition of CPH resulted in the conclusion that, CPH is a high potential feedstock for both thermochemical and biochemical processes. The main focus of the study was the utilization of CPH in 10,000 tons/year power plants for generation of energy and value-added by-products. For this purpose, the feasibility of five energy conversion processes (direct combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization) with CPH as feedstock, were investigated. Several indicators were used for the review and comparison of the technologies. Anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization were found to be the most suitable conversion processes. For both technologies an analysis was conducted including technical, economic, environmental and social aspects. Based on the characterization of CPH, appropriate reactors and operating conditions were chosen for the two processes. Moreover, the plants were chosen to be coupled with CHP units, for heat and power generation. -

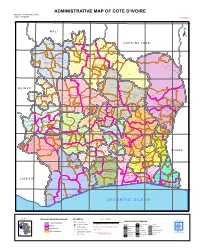

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report October 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action October 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Humanitarian Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives No.1 | October 2011 HIGHLIGHTS ■ The number of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) on 35 sites across the country is gradually decreasing. ■ A National Committee for Coordination of Humanitarian Action (CNCAH) was established by ministerial decree (Minister of State, Employment, Social Affairs and Solidarity) on 5 October 2011. ■ Ivorian refugees in Liberia are spontaneously and gradually returning to their villages of origin in the Moyen Cavally region. ■ The Humanitarian Coordinator and the Ivorian Minister for Employment, Solidarity and Social Affairs visited several European capitals to mobilize support for humanitarian action in Côte d'Ivoire. ■ The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General in Côte d'Ivoire took office on 24 October. I. GENERAL CONTEXT During October, violent incidents took place in the towns of Issia, Guiglo and Bangolo in the West of the country. These incidents resulted in the displacement of an estimated 450 people according to the Protection Cluster. In the Lagunes region, there has been an upsurge of security incidents: several cases of armed robbery, home intrusion and theft are reported to have been committed by armed men in the districts of Anyama, Abobo and Yopougon, in Abidjan. This situation is reportedly due to the free circulation of firearms and to escapee- prisoners since the post-electoral crisis. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Towards Durable Solutions for Displaced Ivoirians

Joint Briefing Paper 11 October 2011 TOWARDS DURABLE SOLUTIONS FOR DISPLACED IVOIRIANS Women returnees in the village of Nedrou in the region of Moyen Cavally receive tools and seeds to rebuild their livelihoods. Photo credit: Thierry Gouegnon/Oxfam 1 Table of content Executive Summary 3 BACKGROUND 5 Context and Scale of Displacement Waves of spontaneous returns REASONS FOR RETURNS AND CONTINUED DISPLACEMENT 6 Reasons for return Reasons for continued displacement Incentives and lack of alternatives Insecurity, fear, rumours, and mixed messages CONTINUED HUMANITARIAN NEEDS 8 Food security and shelter are primary concerns Challenges livelihoods Access to basic services remains limited PROSPECTS FOR SECURITY AND RECONCILIATION 10 Community tensions Need for civilian authorities, reconciliation efforts and the rule of law CONCLUSION 12 RECOMMENDATIONS 13 SURVEY METHODOLOGY 15 Disclaimer The French terms “autochtones”, “allochtones” and “allogenes” are used in this report to refer to the different groups of people living in the country as they are commonly used in Côte d‟Ivoire. This does not reflect the policies or the views of Care, DRC and Oxfam. In the context of the Moyen Cavally region where the study has been conducted, “autochtones” refer to the Guere ethnic group, “allochtones” to all other Ivoirian ethnic groups who migrated to Moyen Cavally and “allogenes” to all the migrants from the ECOWAS countries. The legal bases for durable solutions for displacements are the UNHCR Framework on durable solutions and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacements. The former focuses on promoting durable solutions for refugees and persons of concerns through repatriation to their country of origin, local integration in the country of asylum or resettlement to a third country. -

African Development Bank Cote D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure COTE D’IVOIRE POWER TRANSMISSION AND DISTRIBUTION NETWORKS REINFORCEMENT PROJECT (PRETD) APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure ONEC DEPARTMENT November 2016 Translated Document TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... ii I. IPROJECT PRESENTATION, ALIGNMENT AND BENEFICIARIES ..................................... 1 A. Project Context, Development Objectives and Specific Objectives ....................................... 1 B. Expected Project Outcomes and Impacts ............................................................................... 1 C. Project Outputs ....................................................................................................................... 2 D. Project Rationale..................................................................................................................... 2 E. Project’s Alignment with National Development Goals ........................................................ 2 F. Project Alignment on Bank Strategies and Policies ............................................................... 3 G. Integration of Requirements Set Out Under Presidential Directive No. 02/2005 ................... 3 H. Consultation Process and Ownership by the Country ............................................................ 3 I. Project Target Areas, Beneficiaries and Selection Criteria ....................................................... -

Cocoa Swollen Shoot Disease in Côte D'ivoire

Cocoa Swollen Shoot Disease in Côte D’ivoire: History of Expansion from 2008 to 2016 Romain Aka Aka1, Klotioloma Coulibaly1, Walet Pierre N’guessan1, Koffié Kouakou2, Gnion Mathias Tahi1, Kouamé François N’guessan1, Boubacar Ismaël Kebe1, Evelyne Assi1, Brigitte Guiraud1, Boaké Koné1, Nazaire Kouassi3, Daouda Koné4, Kouassi René Allou1, Emmanuelle Muller5, Nicodème Zakra1 1Cocoa program, National Centre for Agronomic Research (CNRA), BP 808 Divo, Côte d'Ivoire 2ICRAF, World Agroforestry Centre 3Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, WAVE-CI, Pôle Scientifique et d'Innovation Bingerville, BP V 34 Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire 4Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, WASCAL / CEA-CCBAD, Pôle Scientifique et d'Innovation Bingerville 5CIRAD, UMR BGPI, 34398 Montpellier, France Abstract: Cocoa is one of the major cash crop of Cote d’Ivoire. With 1 964 000 tons in 2018, Côte d'Ivoire is leading the world cocoa beans supply. Unfortunately, this important source of income for the country is under a severe pressure of the Cocoa Swollen Shoot Disease. This disease had been reported for the first time in 1943 in the eastern part of the country. In 2003, important infection areas were reported in the departments of Sinfra and Bouaflé in the Central-West with more than 77.000 ha destroyed. Since that period the disease is reported in several places. But we didn’t have a clear idea of all the infected areas. This study aims to study somehow the spread of the disease. The main parameters studied are the incidence and prevalence. The methodological approach consisted in surveys implemented in two steps: 2008-2012 and 2013-2016 on farmer’s farms. -

Intégrer La Gestion Des Inondations Et Des Sécheresses Et De L'alerte

Projet « Intégrer la gestion des inondations et des sécheresses et de l’alerte précoce pour l’adaptation au changement climatique dans le bassin de la Volta » Rapport des consultations nationales en Côte d’Ivoire Partenaires du projet: Rapport élaboré par: CIMA Research Foundation, Dr. Caroline Wittwer, Consultante OMM, Equipe de Gestion du Projet, Avec l’appui et la collaboration des Agences Nationales en Côte d’Ivoire Tables des matières 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 8 2. Profil du Pays ........................................................................................................................................... 10 3. Principaux risques d'inondation et de sécheresse .................................................................................... 14 3.1 Risque d'inondation ......................................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Risque de sécheresse ....................................................................................................................... 18 4. Inondations et Sécheresse : Le bassin de la Volta en Côte d’Ivoire ........................................................ 21 5. Vue d’ensemble du cadre institutionnel .................................................................................................. 27 5.1 Institutions impliquées dans les systèmes d'alerte précoce ............................................................ -

The Immediate Context

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Militarized youths in western Côte d’Ivoire: local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Chelpi, M.L.B. Publication date 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Chelpi, M. L. B. (2011). Militarized youths in western Côte d’Ivoire: local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 86 Photograph 3: Market scene, Man Photograph 4: Rebel taxation on small businesses, Man 5 The immediate context The way western Côte d’Ivoire has been presented since 2002 in the local press and in international reports has been somewhat misleading. -

Diversity of Yeasts Involved in Cocoa Fermentation of Six Major Cocoa-Producing Regions in Ivory Coast

European Scientific Journal October 2017 edition Vol.13, No.30 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Diversity of Yeasts Involved in Cocoa Fermentation of Six Major Cocoa-Producing Regions in Ivory Coast Odilon Koffi, PhD Student, Lamine Samagaci, PhD., Bernadette Goualie, PhD., Sebastien Niamke, PhD., Professor, Laboratoire de Biotechnologie, UFR Biosciences, Université Felix Houphouët-Boigny Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n30p496 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n30p496 Abstract Cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) are the raw material for chocolate production. Fermentation of cocoa pulp is crucial for developing chocolate flavor precursors. This fermentation is led by a succession of complex microbial communities where yeasts play key roles during the first stages of the process. In this study, we identified and analyzed the growth dynamics of yeasts involved in cocoa bean fermentation of six major cocoa- producing regions in Ivory Coast. A total of 743 yeasts were isolated, and were identified by sequencing of D1/D2 regions of 26S rDNA gene. These isolates included 11 species with a predominance of Pichia kudriavzevii (44,81 %), Pichia kluyveri (20,99 %) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (18,97 %) respectively. In addition, the length polymorphism of the genetic marker ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and PCR-RFLP analysis revealed an intraspecific diversity within the three-main species involved in cocoa fermentation of six major local regions in Ivory Coast. This intraspecific diversity could be exploited for selecting appropriate starter cultures. Keywords: Cocoa, fermentation, yeast, diversity, PCR-RFLP Introduction Cocoa fermentation is a crucial step of post-harvest processing of cocoa.