The Immediate Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011

Côte d’Ivoire Rapport Humanitaire Mensuel Novembre 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report November 2011 www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives • Celebrating 20 years of coordinated humanitarian action November 2011 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Bulletin | 2 Côte d’Ivoire Monthly Humanitarian Report Coordination Saves Lives Coordination Saves Lives No. 2 | November 2011 HIGHLIGHTS Voluntary and spontaneous repatriation of Ivorian refugees from Liberia continues in Western Cote d’Ivoire. African Union (AU) delegation visited Duékoué, West of Côte d'Ivoire. Tripartite agreement signed in Lomé between Ivorian and Togolese Governments and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Voluntary return of internally displaced people from the Duekoue Catholic Church to their areas of origin. World Food Program (WFP) published the findings of the post-distribution survey carried out from 14 to 21 October among 240 beneficiaries in 20 villages along the Liberian border (Toulépleu, Zouan- Hounien and Bin-Houyé). Child Protection Cluster in collaboration with Save the Children and UNICEF published The Vulnerabilities, Violence and Serious violations of Child Rights report. The Special Representative of the UN Secretary General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Mrs. Margot Wallström on a six day visit to Côte d'Ivoire. I. GENERAL CONTEXT No major incident has been reported in November except for the clashes that broke out on 1 November between ethnic Guéré people and a group of dozos (traditional hunters). -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

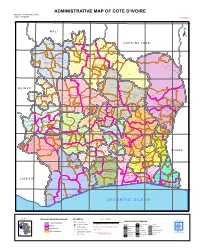

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Cote D'ivoire Summary Full Resettlement Plan (Frp)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT COUNTRY : COTE D’IVOIRE SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Project Team : Mr. R. KITANDALA, Electrical Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Energy Officer ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmental Specialist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consulting Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. A. BERNOUSSI, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. Z. AMADOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Summary FRP Project Name : GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Country : COTE D’IVOIRE Project Number : P-CI-FA0-014 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 INTRODUCTION This document presents the summary Full Resettlement Plan (FRP) of the Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project. It defines the principles and terms of establishment of indemnification and compensation measures for project affected persons and draws up an estimated budget for its implementation. This plan has identified 543 assets that will be affected by the project, while indicating their socio- economic status, the value of the assets impacted, the terms of compensation, and the institutional responsibilities, with an indicative timetable for its implementation. This entails: (i) compensating owners of land and developed structures, carrying out agricultural or commercial activities, as well as bearing trees and graves, in the road right-of-way for loss of income, at the monetary value replacement cost; and (ii) encouraging, through public consultation, their participation in the plan’s planning and implementation. 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND IMPACT AREA 1.1. Project Description and Rationale The Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project seeks to strengthen power transmission infrastructure with a view to completing the primary network, ensuring its sustainability and, at the same time, upgrading its available power and maintaining its balance. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Statistiques Du TONKPI

8 954 192 310 85 717 élèves élèves élèves Avant-Propos La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DRENET MAN / Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 : REGION DU TONKPI 2 Présentation La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la Région.Ce document présente les chiffres et indicateurs essentiels du système éducatif régional. -

Crystal Reports

ELECTION DES DEPUTES A L'ASSEMBLEE NATIONALE SCRUTIN DU 06 MARS 2021 LISTE DEFINITIVE DES CANDIDATS PAR CIRCONSCRIPTION ELECTORALE Region : TONKPI Nombre de Sièges 190 - BIANKOUMA, BLAPLEU, KPATA ET SANTA, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00915 15/01/2021 INDEPENDANT VERT BLANC ADMINISTRATEUR TCHENICIEN T GONETY TIA PROSPER M S LOHI GBONGUE M HOSPITALIER SUPERIEUR Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00929 19/01/2021 INDEPENDANT OR INSPECTEUR DIOMANDE GONDOT GUY T MOUSSA DIOMANDE M S M ETUDIANT PEDAGOGIQUE XAVIER Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01333 21/01/2021 RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX VERT ORANGE ENSEIGNANT ASSISTANT DU T MAMADOU DELY M S GUE BLEU CELESTIN M CHERCHEUR PERSONNEL Page 1 sur 21 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01566 22/01/2021 UDPCI/ARC-EN-CIEL BLEU-CIEL ASSISTANTE DE AGENT DE T GUEI SINGA MIREILLE CHANTAL F S SAHI BADIA JOSEPH M DIRECTION TRANSIT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01576 22/01/2021 INDEPENDANT VERT BLANC T DELI LOUA M COMPTABLE S GOH OLIVIER M ETUDIANT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01809 22/01/2021 ENSEMBLE POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA SOUVERAINETE BLEU CHARRON CYAN BLANC INGENIEUR DES T LOUA ZOMI M S SOUMAHORO ROBERT M PROFFESSEUR TRAVAUX PUBLICS 190 - BIANKOUMA, BLAPLEU, KPATA ET SANTA, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES Page 2 sur 21 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Nombre de Sièges 191 - GBANGBEGOUINE, GBONNE ET GOUINE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00916 15/01/2021 -

From Avoidance to Mitigation: Engaged Communication to Identify and Mitigate

From Avoidance to Mitigation: Engaged Communication to Identify and Mitigate Mining Impacts on Communities by Jodi Hackett © A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL AND INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION We accept the thesis as conforming to the required standard ________________________________________July 8th, 2013 Lite Nartey, Thesis Supervisor Assistant Professor, School Director Darla Moore School of Business University of South Carolina _________________________________________July 9th, 2013 Jennifer Walinga, Internal Committee Member Associate Professor School of Communication & Culture Royal Roads University ________________________________________July 10th, 2013 Wendy Quarry, External Committee Member Associate Faculty School of Communication & Culture Royal Roads University _________________________________________July 9th, 2013 Phillip Vannini, Thesis Coordinator Professor and Canada Research Chair School of Communication & Culture Royal Roads University ii FROM AVOIDANCE TO MITIGATION Copyright 2013 © Jodi Hackett This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author iii FROM AVOIDANCE TO MITIGATION Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to thank Martin Jones for introducing me to my amazing advisor, Lite Nartey. The opportunity to work under the guidance of Lite has been an honor and a saving grace. Thank you Lite for your patience, guidance, understanding, laughter, and your approachability. It goes without saying I would not be in the position I am today had I not had the honor of working with you. I would also like to thank my committee members, Jennifer Walinga and Wendy Quarry for their expertise and contribution to this thesis. Many thanks go to Sama Nickel for graciously opening their doors and taking excellent care of me in Côte d’Ivoire. -

Cote D'ivoire-Programme De Renforcement Des Ouvrages Du

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE UNION – DISCIPLINE – TRAVAIL -------------------------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE ET DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES --------------------------------- PLAN CADRE DE REINSTALLATION DU PROGRAMME DE RENFORCEMENT DES OUVRAGES DU SYSTEME ET D’ACCES A L ’ELECTRICITE (PROSER) DE 253 LOCALITES DANS LES REGIONS DU BAFING, DU BERE, DU WORODOUGOU, DU CAVALLY, DU GUEMON ET DU TONKPI RAPPORT FINAL Octobre 2019 CONSULTING SECURITE INDUSTRIELLE Angré 8ème Tranche, Immeuble ELVIRA Tél :22 52 56 38/ Cel :08 79 54 29 [email protected] Plan Cadre de Réinstallation du Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES ACRONYMES VIII LISTE DES TABLEAUX X LISTE DES PHOTOS XI LISTE DES FIGURES XII DEFINITION DES TERMES UTILISES DANS CE RAPPORT XIII RESUME EXECUTIF XVII 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi 1 1.1.1 Situation de l’électrification rurale en Côte d’Ivoire 1 1.1.2 Justification du plan cadre de réinstallation 1 1.2 Objectifs du PCR 2 1.3 Approche méthodologique utilisée 3 1.3.1 Cadre d’élaboration du PCR 3 1.3.2 Revue documentaire 3 1.3.3 Visites de terrain et entretiens 3 1.4 Contenu et structuration du PCR 5 2 DESCRIPTION DU PROJET 7 2.1 Objectifs -

2005Msfreport-Ivorycoaststi

STI Crisis in the West: Fuelling AIDS In Côte d’Ivoire Médecins Sans Frontières – Holland Ivory Coast April 8, 2005 MSF April 2005 1 I. INTRODUCTION A patient arrives semi-conscious at the Danané Hospital in northwestern Côte d’Ivoire. She has abdominal pain, rebound tenderness and no blood pressure can be detected. The concerned midwife finds that the patient’s vaginal walls are encrusted with a thick solid discharge. This is one of the worst cases of sexually transmitted infection that the midwife has seen in her 20 years of experience. Despite immediate treatment by the hospital staff, the patient goes into cardiac arrest and dies of septic shock. She was 13 years old. The civil war and subsequent collapse of the healthcare system have provoked a medical crisis in parts of Côte d’Ivoire. Responding over the past two years to high levels of malaria, malnutrition and other diseases, Medecins Sans Frontieres (“MSF”) teams in the West of the country have encountered an alarmingly high number of sexually transmitted infections (“STIs”). These STIs lead to horrific complications in reproductive health and carry disease to younger and younger segments of the population. While drastic in its own right, the high level of STIs is also a clear indicator that HIV is spreading, making prevention and treatment efforts all the more urgent. The STI crisis is not a side effect of personal behaviour, but rather a symptom of conditions fuelled by war, displacement and economic desperation. Since the outbreak of conflict in Côte d’Ivoire, MSF has reported on the devastating effects that the conflict has had on the country’s health structures.