From Avoidance to Mitigation: Engaged Communication to Identify and Mitigate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

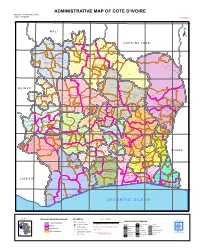

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Statistiques Du TONKPI

8 954 192 310 85 717 élèves élèves élèves Avant-Propos La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DRENET MAN / Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 : REGION DU TONKPI 2 Présentation La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la Région.Ce document présente les chiffres et indicateurs essentiels du système éducatif régional. -

Cote D'ivoire-Programme De Renforcement Des Ouvrages Du

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE UNION – DISCIPLINE – TRAVAIL -------------------------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE ET DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES --------------------------------- PLAN CADRE DE REINSTALLATION DU PROGRAMME DE RENFORCEMENT DES OUVRAGES DU SYSTEME ET D’ACCES A L ’ELECTRICITE (PROSER) DE 253 LOCALITES DANS LES REGIONS DU BAFING, DU BERE, DU WORODOUGOU, DU CAVALLY, DU GUEMON ET DU TONKPI RAPPORT FINAL Octobre 2019 CONSULTING SECURITE INDUSTRIELLE Angré 8ème Tranche, Immeuble ELVIRA Tél :22 52 56 38/ Cel :08 79 54 29 [email protected] Plan Cadre de Réinstallation du Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES ACRONYMES VIII LISTE DES TABLEAUX X LISTE DES PHOTOS XI LISTE DES FIGURES XII DEFINITION DES TERMES UTILISES DANS CE RAPPORT XIII RESUME EXECUTIF XVII 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Programme de Renforcement des Ouvrages du Système et d’accès à l ’Electricité (PROSER) de 253 localités dans les Régions du Bafing, du Béré, du Worodougou, du Cavally, du Guémon et du Tonkpi 1 1.1.1 Situation de l’électrification rurale en Côte d’Ivoire 1 1.1.2 Justification du plan cadre de réinstallation 1 1.2 Objectifs du PCR 2 1.3 Approche méthodologique utilisée 3 1.3.1 Cadre d’élaboration du PCR 3 1.3.2 Revue documentaire 3 1.3.3 Visites de terrain et entretiens 3 1.4 Contenu et structuration du PCR 5 2 DESCRIPTION DU PROJET 7 2.1 Objectifs -

Ion Du Ministere D'etat, Ministere De L'interieur Et De La Securite

PPORT SUR LES ABUS DES DROITS DE L'HOMME COMMIS PAR DES DOZOS EN RÉPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D'IVOIRE ION DU MINISTERE D'ETAT, MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR ET DE LA SECURITE Dans un rapport en date du mois de juin 2013, l'ONUCI et le bureau du Haut Commissariat aux Droits de l'Homme ont traité les abus des droits de l'homme commis par les Dozos en Côte d'Ivoire. Certaines recommandations formulées dans ce rapport font déjà l'objet de mesures en cours ou déjà exécuté au Ministère d'Etat, Ministère de l'Intérieur et de la Sécurité. 1. RAPPEL DES RECOMMANDATIONS DU RAPPORT Le rapport recommande aux autorités ivoiriennes: de déoloyer des forces de sécurité, de façon permanente et sur l'ensemble du territoire national afin de limiter le recours de la population aux Dozos et de renforcer la confiance entre ceux-ci et la population, notamment dans les localités où les forces de l'ordre sont inexistantes; de doter ces dernières de la formation et de moyens logistiques adéquats et les encourager à la discipline pour mener à bien leurs missions de défense et de protection des personnes et des biens; de mettre en œuvre toutes les mesures nécessaires afin que les Dozos cessent d'exercer des fonctions en matière de sécurité; d'inciter et d'accompagner les Dozos à mener un recensement général de leurs effectifs; de prendre toutes les mesures nécessaires pour s'assurer que les Dozos se conforment aux prescriptions du décret du 4 juillet 2012 portant réglementation des armes et des munitions en Côte d'Ivoire. -

Intégrer La Gestion Des Inondations Et Des Sécheresses Et De L'alerte

Projet « Intégrer la gestion des inondations et des sécheresses et de l’alerte précoce pour l’adaptation au changement climatique dans le bassin de la Volta » Rapport des consultations nationales en Côte d’Ivoire Partenaires du projet: Rapport élaboré par: CIMA Research Foundation, Dr. Caroline Wittwer, Consultante OMM, Equipe de Gestion du Projet, Avec l’appui et la collaboration des Agences Nationales en Côte d’Ivoire Tables des matières 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 8 2. Profil du Pays ........................................................................................................................................... 10 3. Principaux risques d'inondation et de sécheresse .................................................................................... 14 3.1 Risque d'inondation ......................................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Risque de sécheresse ....................................................................................................................... 18 4. Inondations et Sécheresse : Le bassin de la Volta en Côte d’Ivoire ........................................................ 21 5. Vue d’ensemble du cadre institutionnel .................................................................................................. 27 5.1 Institutions impliquées dans les systèmes d'alerte précoce ............................................................ -

The Immediate Context

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Militarized youths in western Côte d’Ivoire: local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Chelpi, M.L.B. Publication date 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Chelpi, M. L. B. (2011). Militarized youths in western Côte d’Ivoire: local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 86 Photograph 3: Market scene, Man Photograph 4: Rebel taxation on small businesses, Man 5 The immediate context The way western Côte d’Ivoire has been presented since 2002 in the local press and in international reports has been somewhat misleading. -

Ex-Rebel Commanders and Postwar Statebuilding: Subnational Evidence from Cˆoted’Ivoire

Ex-Rebel Commanders and Postwar Statebuilding: Subnational Evidence from C^oted'Ivoire Philip Andrew Martin* Abstract Ex-rebel commanders play a central role in peacebuilding after civil war, often deciding where governments consolidate authority and whether states relapse into vio- lence. Yet the influence and mobilization power of these actors is not uniform: in some areas commanders retain strong social ties to civilian populations after integrating into the state, while in other areas such ties wither away. What accounts for this variation? This article advances a theory of local goods provision and political accountability to explain why commander-community linkages endure or decline after post-conflict tran- sitions. Drawing on multiple data sources from C^oted'Ivoire | including an original survey of community informants in former rebel-occupied regions | it shows that com- manders retained social capital and access to networks of supporters in areas where insurgents provided essential goods to civilians during war. Where insurgents' wartime rule involved coercion and abuse, by contrast, ex-rebel commanders were more likely to lose influence and mobilization power. These findings challenge existing theories of rebel institution-building and state formation, suggesting that effective governance can help armed movements build popular support and win civil wars, but simultaneously create regionally-embedded strongmen who are able to facilitate but also resist the centralizing efforts of state rulers. *PhD Candidate, Department of Political Science, MIT. Predoctoral Research Fel- low, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. Email: [email protected]. The Puzzle: Commander-Community Ties After Civil War The towns of Sangouin´eand Mahapleu in western C^oted'Ivoire were both occupied by the Forces Nouvelles (FN) rebel movement during the Ivorian civil war (2002-2011). -

Technical Report on the Samapleu Nickel and Copper Deposits Côte D’Ivoire, West Africa

TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE SAMAPLEU NICKEL AND COPPER DEPOSITS CÔTE D’IVOIRE, WEST AFRICA DECEMBER 2015 TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE SAMAPLEU NICKEL AND COPPER DEPOSITS CÔTE D’IVOIRE, WEST AFRICA Sama Resources Inc. – Ressources Sama Inc. Project no: 121-26251-00 Re-issue date: December 22, 2015 Original Issue Date: August 22, 2013 Resource Effective Date: December 11, 2012 Report Effective Date: July 1, 2013 Prepared by: Mohammed Ali Ben Ayad, Ph.D., Geo Claire Hayek, Eng. MBA Jean Corbeil, Eng. Pierre-Jean Lafleur, Eng. – WSP Canada Inc. 1600, René-Lévesque Blvd. West, 16th Floor Montréal, Québec H3H 1P9 Phone: +1 514-340-0046 Fax: +1 514-340-1337 www.wspgroup.com SIGNATURES Original signed and dated by Mohammed Ali Ben Ayad, Ph.D. Geo 2015-12-22 Mohammed Ali Ben Ayad, Ph.D. Geo Date Associate Geologist of P.J. Lafleur Géo-Conseils Inc. Original signed and dated by Jean Corbeil, Eng. 2015-12-22 Jean Corbeil, Eng. Date Director, Project Management WSP Canada Inc. Original signed and dated by Claire Hayek, Eng., MBA 2015-12-22 Claire Hayek, Eng. MBA Date Mineral Processing Director WSP Canada Inc. Original signed and dated by Pierre-Jean Lafleur, Eng. 2015-12-22 Pierre-Jean Lafleur, Eng. Date Geological Engineer P.J. Lafleur Géo-Conseils Inc. i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 PROPERTY OVERVIEW ...................................................................................... -

African Development Bank Group

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATIN PROJECT COUNTRY : COTE D’IVOIRE SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Project Team: R. KITANDALA, Power Engineer, ONEC.1 P. DJAIGBE, Chief Energy Officer, ONEC.1/SNFO M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 S. BAIOD, Environmentalist/Consultant, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: A. RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: J.K. LITSE, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: A. ZAKOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1 1 GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT ESIA Summary Project Name : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Country : COTE D’IVOIRE Project Reference Number : P-CI-FA0-014 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is the summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project. The project ESIA was prepared in August 2015. This summary was prepared in accordance with Ivoirian environmental and social requirements and the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category I projects. The project description and rationale are first presented followed by the country’s legal and institutional framework. The description of the project’s main environmental conditions is presented as well as options that are compared in terms of technical, economic, environmental and social feasibility. Environmental and social impacts are summarised and inevitable ones identified during the preparation, construction and operational phases of the transmission lines. Next, it recommends improvement measures such as rural electrification, mitigation measures proposed to enhance benefits and/or prevent and minimise negative impacts, and a monitoring programme. Public consultations held during the conduct of the ESIA are presented along with complementary project-related initiatives.