Ex-Rebel Commanders and Postwar Statebuilding: Subnational Evidence from Cˆoted’Ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

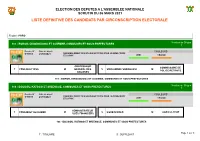

Crystal Reports

ELECTION DES DEPUTES A L'ASSEMBLEE NATIONALE SCRUTIN DU 06 MARS 2021 LISTE DEFINITIVE DES CANDIDATS PAR CIRCONSCRIPTION ELECTORALE Region : PORO Nombre de Sièges 163 - BORON, DIKODOUGOU ET GUIEMBE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00665 21/01/2021 RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX VERT ORANGE CONTROLEUR COMMISSAIRE DE T COULIBALY ISSA M GENERAL DES S SOULAMANE SAMAGASSI M POLICE RETRAITE DOUANES 163 - BORON, DIKODOUGOU ET GUIEMBE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES Nombre de Sièges 164 - BOUGOU, KATOGO ET M'BENGUE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00666 21/01/2021 RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX VERT ORANGE ADMINISTRATEUR T COULIBALY ALI KADER M S SILUE N'GOLO M AGRICULTEUR SCES FINANCIERS 164 - BOUGOU, KATOGO ET M'BENGUE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES Page 1 sur 9 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Nombre de Sièges 165 - KATIALI ET NIOFOIN, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES, N'GANON SOUS-PREFECTURE 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00655 16/01/2021 INDEPENDANT BLANC BLEUE T SORO ZIE SAMUEL M ETUDIANT S MASSAFONHOUA SEKONGO M INSTITUTEUR Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00663 20/01/2021 INDEPENDANT VERT BLANC T SORO WANIGNON M INGENIEUR S SEKONGO ZANGA M AGENT DE POLICE Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00667 21/01/2021 RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX VERT ORANGE INGENIEUR DES T SORO FOBEH M S KANA YEO M COMMERCANT TRANSPORTS 165 - KATIALI ET NIOFOIN, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES, N'GANON -

Dossier D'appel D'offres TRAVAUX DE REVITALISATION DES

République de Côte d’Ivoire Union - Discipline- Travail MINISTERE DE LA SANTE ET DE L’HYGIENE PUBLIQUE ----------------------- UNITE DE COORDINATION DES PROJETS C2D SANTE ----------------------- Programme de Renforcement du Système de Santé 2 (Convention d'affectation N° CCI 1480 01 G) Dossier d’Appel d’Offres TRAVAUX DE REVITALISATION DES ETABLISSEMENTS SANITAIRES DE PREMIER CONTACT DANS LA DIRECTION REGIONALE DE LA SANTE DE KORHOGO Appel d’offres ouvert N° : T 787/ 2019 Septembre 2019 Unité de Coordination des Projets C2D Santé – 04 BP 2409 Abidjan 04 – Abidjan, Plateau, ème Rue Thomasset, immeuble Saint Augustin, 6 étage – Tél : 20 24 22 07 UCP C2D SANTE Description Sommaire i Sommaire PREMIÈRE PARTIE – PROCÉDURES D’APPEL D’OFFRES Section 0 Avis d’Appel d’Offres Cette section contient des modèles d’avis d’appel d’offres, selon la méthode d’appel d’offres utilisée : Appel d’Offres(AO) non précédé de présélection, AO après présélection, ou AO restreint, respectivement. Section I Instructions aux Candidats (IC) Cette section fournit aux Candidats les informations utiles pour préparer leurs soumissions. Elle comporte aussi des renseignements sur la soumission, l’ouverture des plis et l’évaluation des offres, et sur l’attribution des marchés. Les dispositions figurant dans cette Section I ne doivent pas être modifiées. Section II Données Particulières de l’Appel d’Offres (DPAO) Cette section énonce les dispositions propres à chaque passation de marché, qui complètent les informations ou conditions figurant à la Section I - Instructions aux Candidats. Section III Critères d’évaluation et de qualification Cette section contient tous les facteurs, méthodes et critères que l’Autorité contractante utilisera pour s’assurer qu’un Candidat possède les qualifications requises. -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

KORHOGO Etude De Développement Socio-Économique

RÉPUBLIQUE' DE COTE D'IVOIRE Ministère des Finances',, des Affaires éc_onomiques et du Plan , .,r, . • ,r • • ~~ DE KORHOGO Etude de développement socio-économique ., 1. D. E. P. LE COMMERCE ET LES TRANSPORTS - SOCIÉTÉ D'ÉTUDES POUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONO· , MIQUE ET ,SOCIAL - 67, RUE DE LILLE • PARIS-7• 1 1 ' ; ' ' RÉPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE Ministère des Finance , des Affaires économiques et du Plan RÉGION DE I<OR OGO Etude de développement socio-économique LE COMMERCE ET LES TRANSPORTS SOCIËTË D'ËTUDES POUR LE DËVELOPPEMENT ËCONO M IQUE ET SOCIAL - 67 RUE DE LILLE - PARIS-7• Se ptembre 1965 Le présent rapport a été rédigé par M. Gilbert RATHERY, chargé d'études à la Société d'Études pour le Développement Économique et Social LE COMMERCE ET LES TRANSPORTS ERRATUM Page 10 - L'introduction méthodologique se termine sous le tableau après le 2• alinéa. Tous les alinéas suivants, à partir de la phrase: " Les marchés ont dû naître spontanément du besoin 7 d'échanges que ressentent les hommes "··· doivent se placer page 11, sous le paragraphe a) Marchés, après la phrase " La plupart des marchés sont d'institu tiort très ancienne "· l1 Le paragraphe " Développement du commerce , devient alors c) au lieu de b) qui est constitué par: Unités de mesure et monnaie "· l1 Page 108 - Tableau No 43 CT lire : quantités enregistrées dans le sens SUD-NORD et ~ 1 non pas NORD-SUD. .1 Page 109 - Tableau No 44 CT - 2• partie .6 lire : sens SUD-NORD (destination Korhogo). 12 Page 110 · Dans le 3" paragraphe de B - Le trafic ferroviaire lire : " Le tableau No 49 CT donne la répartition mensuelle 12 du trafic .. -

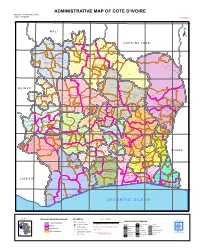

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

5 Geology and Groundwater 5 Geology and Groundwater

5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER 5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 PRESENT CONDITIONS OF TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY.................................................................... 5 – 1 1.1 Topography............................................................................................................... 5 – 1 1.2 Geology.................................................................................................................... 5 – 2 1.3 Hydrogeology and Groundwater.............................................................................. 5 – 4 CHAPTER 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES POTENTIAL ............................... 5 – 13 2.1 Mechanism of Recharge and Flow of Groundwater ................................................ 5 – 13 2.2 Method for Potential Estimate of Groundwater ....................................................... 5 – 13 2.3 Groundwater Potential ............................................................................................. 5 – 16 2.4 Consideration to Select Priority Area for Groundwater Development Project ........ 5 – 18 CHAPTER 3 GROUNDWATER BALANCE STUDY .............................................. 5 – 21 3.1 Mathod of Groundwater Balance Analysis .............................................................. 5 – 21 3.2 Actual Groundwater Balance in 1998 ...................................................................... 5 – 23 3.3 Future Groundwater Balance in 2015 ...................................................................... 5 – 24 CHAPTER -

Cote D'ivoire Summary Full Resettlement Plan (Frp)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : GRID REINFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT COUNTRY : COTE D’IVOIRE SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Project Team : Mr. R. KITANDALA, Electrical Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Energy Officer ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmental Specialist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Consulting Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. A. BERNOUSSI, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. Z. AMADOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Summary FRP Project Name : GRID REIFORCEMENT AND RURAL ELECTRIFICATION PROJECT Country : COTE D’IVOIRE Project Number : P-CI-FA0-014 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 INTRODUCTION This document presents the summary Full Resettlement Plan (FRP) of the Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project. It defines the principles and terms of establishment of indemnification and compensation measures for project affected persons and draws up an estimated budget for its implementation. This plan has identified 543 assets that will be affected by the project, while indicating their socio- economic status, the value of the assets impacted, the terms of compensation, and the institutional responsibilities, with an indicative timetable for its implementation. This entails: (i) compensating owners of land and developed structures, carrying out agricultural or commercial activities, as well as bearing trees and graves, in the road right-of-way for loss of income, at the monetary value replacement cost; and (ii) encouraging, through public consultation, their participation in the plan’s planning and implementation. 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND IMPACT AREA 1.1. Project Description and Rationale The Grid Reinforcement and Rural Electrification Project seeks to strengthen power transmission infrastructure with a view to completing the primary network, ensuring its sustainability and, at the same time, upgrading its available power and maintaining its balance. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Annuaire Statistique D'état Civil 2018

1 2 3 REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE Union – Discipline – Travail MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR ET DE LA SECURITE ----------------------------------- DIRECTION DES ETUDES, DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI-EVALUATION ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE D'ETAT CIVIL 2018 Les personnes ci-après ont contribué à l’élaboration de cet annuaire : MIS/DEPSE - Dr Amoncou Fidel YAPI - Ange-Lydie GNAHORE Epse GANNON - Taneaucoa Modeste Eloge KOYE MIS/DGAT - Roland César GOGO MIS/DGDDL - Botty Maxime GOGONE-BI - Simon Pierre ASSAMOI MJDH/DECA - Rigobert ZEBA - Kouakou Charles-Elie YAO MIS/ONECI - Amone KOUDOUGNON Epse DJAGOURI MSHP/DIIS - Daouda KONE MSHP/DCPEV - Moro Janus AHI SOUS-PREFECTURE DE - Affoué Jeannette KOUAKOU Epse GUEI JACQUEVILLE SOUS-PREFECTURE DE KREGBE - Hermann TANO MPD/INS - Massoma BAKAYOKO - N'Guethas Sylvie Koutoua GNANZOU - Brahima TOURE MPD/ONP - Bouangama Didier SEMON INTELLIGENCE MULTIMEDIA - Gnekpié Florent YAO - Cicacy Kwam Belhom N’GORAN UNICEF - Mokie Hyacinthe SIGUI 1 2 PREFACE Dans sa marche vers le développement, la Côte d’Ivoire s’est dotée d’un Plan National de Développement (PND) 2016-2020 dont l’une des actions prioritaires demeure la réforme du système de l’état civil. A ce titre, le Gouvernement ivoirien a pris deux (02) lois portant sur l’état civil : la loi n°2018-862 du 19 novembre 2018 relative à l’état civil et la loi n°2018-863 du 19 novembre 2018 instituant une procédure spéciale de déclaration de naissance, de rétablissement d’identité et de transcription d’acte de naissance. La Côte d’Ivoire attache du prix à l’enregistrement des faits d’état civil pour la promotion des droits des individus, la bonne gouvernance et la planification du développement. -

Statistiques Du TONKPI

8 954 192 310 85 717 élèves élèves élèves Avant-Propos La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DRENET MAN / Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 : REGION DU TONKPI 2 Présentation La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020 de la Région.Ce document présente les chiffres et indicateurs essentiels du système éducatif régional. -

Crystal Reports

ELECTION DES DEPUTES A L'ASSEMBLEE NATIONALE SCRUTIN DU 06 MARS 2021 LISTE DEFINITIVE DES CANDIDATS PAR CIRCONSCRIPTION ELECTORALE Region : TONKPI Nombre de Sièges 190 - BIANKOUMA, BLAPLEU, KPATA ET SANTA, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00915 15/01/2021 INDEPENDANT VERT BLANC ADMINISTRATEUR TCHENICIEN T GONETY TIA PROSPER M S LOHI GBONGUE M HOSPITALIER SUPERIEUR Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00929 19/01/2021 INDEPENDANT OR INSPECTEUR DIOMANDE GONDOT GUY T MOUSSA DIOMANDE M S M ETUDIANT PEDAGOGIQUE XAVIER Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01333 21/01/2021 RASSEMBLEMENT DES HOUPHOUETISTES POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX VERT ORANGE ENSEIGNANT ASSISTANT DU T MAMADOU DELY M S GUE BLEU CELESTIN M CHERCHEUR PERSONNEL Page 1 sur 21 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01566 22/01/2021 UDPCI/ARC-EN-CIEL BLEU-CIEL ASSISTANTE DE AGENT DE T GUEI SINGA MIREILLE CHANTAL F S SAHI BADIA JOSEPH M DIRECTION TRANSIT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01576 22/01/2021 INDEPENDANT VERT BLANC T DELI LOUA M COMPTABLE S GOH OLIVIER M ETUDIANT Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-01809 22/01/2021 ENSEMBLE POUR LA DEMOCRATIE ET LA SOUVERAINETE BLEU CHARRON CYAN BLANC INGENIEUR DES T LOUA ZOMI M S SOUMAHORO ROBERT M PROFFESSEUR TRAVAUX PUBLICS 190 - BIANKOUMA, BLAPLEU, KPATA ET SANTA, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES Page 2 sur 21 T : TITULAIRE S : SUPPLEANT Nombre de Sièges 191 - GBANGBEGOUINE, GBONNE ET GOUINE, COMMUNES ET SOUS-PREFECTURES 1 Dossier N° Date de dépôt COULEURS U-00916 15/01/2021