University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nopf Leday Hing Up

Fall 2009 THE KNOPF DOUBLEDAY PUBLISHING GROUP DOUBLEDAY The Knopf NAN A. TALESE Doubleday KNOPF Publishing PANTHEON SCHOCKEN Group EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY VINTAGE ANCHOR THE IMPRINTS OF THE KNOPF DOUBLEDAY GROUP AND THEIR COLOPHONS Catalog, Final files_cvr_MM AA.indd 1 3/5/09 6:48:32 PM Fa09_TOC_FINAL_r2.qxp 3/10/09 12:05 PM Page 1 The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group Fall 2009 Doubleday and Nan A. Talese.............................................................3 Alfred A. Knopf................................................................................43 Pantheon and Schocken ..................................................................107 Everyman’s Library........................................................................133 Vintage and Anchor........................................................................141 Group Author Index .......................................................................265 Group Title Index ...........................................................................270 Foreign Rights Representatives ........................................................275 Ordering Information .....................................................................276 Fa09_TOC_FINAL.qxp:Fa09_TOC 3/6/09 2:13 PM Page 2 Doubleday DdAaYy Nan A. Talese Catalog, Final files_dvdrs_MM AA.indd 3 3/5/09 6:43:33 PM DD-Fa09_FINAL MM.qxp 3/6/09 3:53 PM Page 3 9 0 0 2 L L FA DD-Fa09_FINAL MM.qxp 3/6/09 3:53 PM Page 4 DD-Fa09_FINAL MM.qxp 3/6/09 3:53 PM Page 5 INDEXF O A UTHORS Ackroyd, Peter, THE CASEBOOK Lethem, Jonathan, -

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010

ETHIOPIA - National Hot Spot Map 31 May 2010 R Legend Eritrea E Tigray R egion !ª D 450 ho uses burned do wn d ue to th e re ce nt International Boundary !ª !ª Ahferom Sudan Tahtay Erob fire incid ent in Keft a hum era woreda. I nhabitan ts Laelay Ahferom !ª Regional Boundary > Mereb Leke " !ª S are repo rted to be lef t out o f sh elter; UNI CEF !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Gulomekeda W W W 7 Dalul E !Ò Laelay togethe r w ith the regiona l g ove rnm ent is Zonal Boundary North Western A Kafta Humera Maychew Eastern !ª sup portin g the victim s with provision o f wate r Measle Cas es Woreda Boundary Central and oth er imm ediate n eeds Measles co ntinues to b e re ported > Western Berahle with new four cases in Arada Zone 2 Lakes WBN BN Tsel emt !A !ª A! Sub-city,Ad dis Ababa ; and one Addi Arekay> W b Afa r Region N b Afdera Military Operation BeyedaB Ab Ala ! case in Ahfe rom woreda, Tig ray > > bb The re a re d isplaced pe ople from fo ur A Debark > > b o N W b B N Abergele Erebtoi B N W Southern keb eles of Mille and also five kebeles B N Janam ora Moegale Bidu Dabat Wag HiomraW B of Da llol woreda s (400 0 persons) a ff ected Hot Spot Areas AWD C ases N N N > N > B B W Sahl a B W > B N W Raya A zebo due to flo oding from Awash rive r an d ru n Since t he beg in nin g of th e year, Wegera B N No Data/No Humanitarian Concern > Ziquala Sekota B a total of 967 cases of AWD w ith East bb BN > Teru > off fro m Tigray highlands, respective ly. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Download Itunes About Journalism to Propose Four Use—Will Be Very Different

Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 4 WINTER 2008 4 The Search for True North: New Directions in a New Territory Spiking the Newspaper to Follow the Digital Road 5 If Murder Is Metaphor | By Steven A. Smith 7 Where the Monitor Is Going, Others Will Follow | By Tom Regan 9 To Prepare for the Future, Skip the Present | By Edward Roussel 11 Journalism as a Conversation | By Katie King 13 Digital Natives: Following Their Lead on a Path to a New Journalism | By Ronald A. Yaros 16 Serendipity, Echo Chambers, and the Front Page | By Ethan Zuckerman Grabbing Readers’ Attention—Youthful Perspectives 18 Net Geners Relate to News in New Ways | By Don Tapscott 20 Passion Replaces the Dullness of an Overused Journalistic Formula | By Robert Niles 21 Accepting the Challenge: Using the Web to Help Newspapers Survive | By Luke Morris 23 Journalism and Citizenship: Making the Connection | By David T.Z. Mindich 26 Distracted: The New News World and the Fate of Attention | By Maggie Jackson 28 Tracking Behavior Changes on the Web | By David Nicholas 30 What Young People Don’t Like About the Web—And News On It | By Vivian Vahlberg 32 Adding Young Voices to the Mix of Newsroom Advisors | By Steven A. Smith 35 Using E-Readers to Explore Some New Media Myths | By Roger Fidler Blogs, Wikis, Social Media—And Journalism 37 Mapping the Blogosphere: Offering a Guide to Journalism’s Future | By John Kelly 40 The End of Journalism as Usual | By Mark Briggs 42 The Wikification of Knowledge | By Kenneth S. -

Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours the Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia

Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4 Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant September 1994 Please send comments on this paper to: Relief and Rehabilitation Network Overseas Development Institute Regent's College Inner Circle Regent's Park London NW1 4NS United Kingdom A copy will be sent to the author. Comments received may be used in future Newsletters. ISSN: 1353-8691 © Overseas Development Institute, London, 1994. Photocopies of all or part of this publication may be made providing that the source is acknowledged. Requests for commercial reproduction of Network material should be directed to ODI as copyright holders. The Network Coordinator would appreciate receiving details of any use of this material in training, research or programme design, implementation or evaluation. Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant1 Contents Page Maps 1. Introduction 1 2. Pride and Prejudice in the Somali Region 5 : The Political History of a Conflict 3 * The Ethiopian empire-state and the colonial powers 4 * Greater Somalia, Britain and the growth of Somali nationalism 8 * Conflict and war between Ethiopia and Somalia 10 * Civil war in Somalia 11 * The Transitional Government in Ethiopia and Somali Region 5 13 3. Cycles of Relief and Rehabilitation in Eastern Ethiopia : 1973-93 20 * 1973-85 : `Relief shelters' or the politics of drought and repatriation 21 * 1985-93 : Repatriation as opportunity for rehabilitation and development 22 * The pastoral sector : Recovery or control? 24 * Irrigation schemes : Ownership, management and economic viability 30 * Food aid : Targeting, free food and economic uses of food aid 35 * Community participation and institutional strengthening 42 1 Koenraad Van Brabant has been project manager relief and rehabilitation for eastern Ethiopia with SCF(UK) and is currently Oxfam's country representative in Sri Lanka. -

Russia's Role in the Horn of Africa

Russia Foreign Policy Papers “E O” R’ R H A SAMUEL RAMANI FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE • RUSSIA FOREIGN POLICY PAPERS 1 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Samuel Ramani The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy- oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities. Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Editing: Thomas J. Shattuck Design: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute July 2020 OUR MISSION The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. We educate those who make and influence policy, as well as the public at large, through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S. -

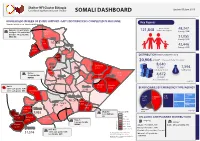

Somali Dashboard +Distribution Breakdown

Shelter-NFI Cluster Ethiopia Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SOMALI DASHBOARD Update 05 June 2018 HOUSEHOLDS IN NEED OF ES/NFI SUPPORT- GAP*/ DISTRIBUTIONS COMPLETED IN MAY/JUNE Key Figures *Number of HH inGA need - Number of HH suported HH in need of 48,347 Gablalu- 100 partial kits 121,848 Shelter/ NFI support Hadigala- 330 partial kits Gablablu Priority 1 HH Dembel- 140 partial kits 1,673 ERCS/IRC 31,055 Siti Priority 2 HH Erer 10,808 2,630 Fafan 42,446 Miesso Priority 3 HH 3,598 15,157 Jijiga DISTRIBUTION SINCE JANUARY 2018 Babile 1,464 10, 592 20,906 (2,482)* HH received Shelter/ NFI support Erer Gashamo 8,640 4,941 Jarar 3, 733 (1,390)* 7,594 Full Shelter/NFI kits Cash Grants Qubi 7, 343 S Berano Boh 2,114 500 partial kits Noqob Danot Doolo 1,546 4,672 NDRMC 2,537 (1,102)* 3,841 Gerbo 12,068 Partial Shelter/NFI kits 1,476 on-going* Warder Geladin Hudet Korahe 3,712 2,144 BENEFICIARIES BY EMERGENCY TYPE/AGENCY 1,500 cash grants- IOM 3,193 1,000 cash grants- NRC Guradamole Berano 2,720 290 NRC CONCERN CONFLICTIOM Shabelle FLOOD CONFLICT 3,630 2,602 9,0507,094 7,462 9,050 Karsa Dulla 16, 578 (2,482)* IRC/ERCS Afder Kelafo 2,570 1,449 Hargele 9,520 SCI 7,033 702 Mustahil 3,000 NDRMC 2,000 Deka Suftu 3,419 Liben DROUGHT 2,364 on-going* Mustahil Number of HH 3,814 9,955 1,000 fulll kits Hudet 0 SCI 1 - 500 12,718 Mubarak ON-GOING AND PLANNED DISTRIBUTIONS Dolo Odo 500 - 1,000 6,002 Hargele on-going 1,989 1,500 partial kits 1,000 - 2,000 planned 2,000 - 5,000 Moyale NDRMC Adadle- 750 full kits /NRC Kelafo- 450 partial kits /SCI 5,000 -

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility

Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility Africa Program Working Paper Series Gilbert M. Khadiagala OCTOBER 2008 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: Elderly women receive ABOUT THE AUTHOR emergency food aid, Agok, Sudan, May 21, 2008. ©UN Photo/Tim GILBERT KHADIAGALA is Jan Smuts Professor of McKulka. International Relations and Head of Department, The views expressed in this paper University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South represent those of the author and Africa. He is the co-author with Ruth Iyob of Sudan: The not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Elusive Quest for Peace (Lynne Rienner 2006) and the welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit editor of Security Dynamics in Africa’s Great Lakes of a well-informed debate on critical Region (Lynne Rienner 2006). policies and issues in international affairs. Africa Program Staff ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS John L. Hirsch, Senior Adviser IPI owes a great debt of thanks to the generous contrib- Mashood Issaka, Senior Program Officer utors to the Africa Program. Their support reflects a widespread demand for innovative thinking on practical IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor solutions to continental challenges. In particular, IPI and Ellie B. Hearne, Publications Officer the Africa Program are grateful to the government of the Netherlands. In addition we would like to thank the Kofi © by International Peace Institute, 2008 Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre, which All Rights Reserved co-hosted an authors' workshop for this working paper series in Accra, Ghana on April 11-12, 2008. www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen . i Introduction. 1 Key Challenges . -

Assessing Freight Transport Performances in Relation to Delays

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING Assessing Freight Transport Performances in Relation to Delays in Ethiopia: the case of Addis Ababa-Djibouti Corridor A Thesis Submitted to Road & Transport Engineering Stream By Kalkidan Waktole Bedassa Presented In Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Civil and Environmental Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Kalkidan Waktole, entitled: Assessing Freight Transport Performances in Relation to Delays in Ethiopia: the case of Addis Ababa-Djibouti Corridor and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Civil and Environmental Engineering) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the Examining Committee: Mr. Abel Kebede Internal Examiner Signature Date Dr. Alemayehu Ambo External Examiner Signature Date Professor Girma Gebresenbet Advisor Signature Date ___________________________________________ School or Center Chair Person ii UNDERTAKING I certify that this research work titled by Assessing Freight Transport Performances in Relation to Delays in Ethiopia: The case on Addis Ababa-Djibouti Corridor is my own work. The work has not been presented elsewhere for assessment. Where material has been used from other sources it has been properly acknowledged / referred. Kalkidan Waktole iii ABSTRACT The major contributing factor for low level of logistic performance in Ethiopia is freight transport delay. Delay affects trade performance of a country in terms of cost, time, reliability, predictability and customer services. -

Ethiopia – Flooding Flash Update 3

Ethiopia – Flooding Flash Update 3 22 May 2018 On 21 May, the National Disaster Risk Management Commission (NDRMC)-led Flood Task Force issued a revised Flood Alert1, based on the monthly National Meteorology Agency (NMA) forecast for the month of May 2018. The latest NMA forecast informs of a shift of the heavy rainfall from south eastern Ethiopia (mainly Somali region) to the central, western and parts of northern Ethiopia, including Afar, Amhara, Gambella, southern Oromia, parts of SNNP and Tigray region. Accordingly, average to above average rainfall is expected in Zones 3, 4 and 5 of Afar region; North and South Wello, North and South Gonder, Bahir Dar Zuria, Western and Eastern Gojam, and Awi zones of Amhara region; Benishan- gul Gumuz region; Gambella region; Harari region; Arsi, Bale, Borena, Guji, eastern, northern and western Shewa, East and West Hararge zones of Oromia region; most zones of SNNPR; most of Somali region; Tigray region; as well as Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa cities. The rains are expected to benefit agricultural activities by improving moisture forbelg and long cycle meher crops and perennial plants; and to help pasture regeneration and water source replenishment. However, flash floods are anticipated in areas along river banks and areas with low soil water percolation capacity. The first Alert was issued on 27 April following the reactivation of the National Flood Task Force on 19 April, to co- ordinate flood mitigation, preparedness and response efforts. Another revision will be conducted based on NMA’s forecast for the 2018 summer kiremt rains and new developments on the ground. -

Ethiopia: Bank Group Assistance to the Transport Sector

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP ETHIOPIA: BANK GROUP ASSISTANCE TO THE TRANSPORT SECTOR OPERATIONS EVALUATION DEPARTMENT (OPEV) APRIL 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective of Study 1 1.2 Scope 1 2. BANK GROUP STRATEGY & ASSISTANCE 2 2.1 Transport Policy 2 2.2 Strategy in the Transport Sector in Ethiopia 4 2.3 Bank Assistance 5 3. GOVERNMENT STRATEGY 5 4. DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS OF BANK ASSISTANCE 6 4.1 Objectives 6 4.2 Relevance 7 4.3 Efficacy 8 5. EFFICIENCY OF IMPLEMENTATION 10 5.1 Implementation Schedules 10 5.2 Cost Variations and Loan Utilization 12 5.3 Economic Rates of Return 12 5.4 Bank Performance 13 5.5 Borrower Performance 15 5.6 Co-financing & Donor Co-ordination 16 6. IMPACT OF BANK ASSISTANCE 17 6.1 Project Outcomes 17 6.2 Socio-economic Impact and Poverty Alleviation 18 6.3 Impact on Women 20 6.4 Environmental Impact 21 6.5 Private Sector Participation 22 6.6 Regional Economic Integration 23 7. INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND CAPACITY BUILDING 24 7.1 Background 24 7.2 Recent Capacity Building Efforts 25 7.3 Further Capacity Building 27 8. SUSTAINABILITY 28 9. KEY ISSUES FOR ENHANCEMENT OF DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS 29 9.1 Rural Roads 29 9.2 Road Maintenance 31 10. CONCLUSION, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 34 10.1 Conclusion 34 10.2 What Have We Learned – Findings and Lessons 35 10.3 The Way Forward- Recommendations 37 ANNEXURES Annexure N° of Pages 1 Bank Assistance to Transport Sector 1 2 Summary of Bank Group Operations as at 31 July 2001 3 3 Objectives and Project Components 3 4 Project Implementation Schedule 1 5 Project Costs 2 6 Loan Amounts and Disbursements 1 7 Economic Internal Rates of Return 1 8 Agricultural Production in Districts covered by Rural Roads I & II Projects 1 9 Allocations and Expenditure from the Road Fund 1 10 Key Lessons and Recommendations 3 This report was prepared by Mr. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations.