Eastern Africa: Security and the Legacy of Fragility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Managing Ethiopia's Transition

Managing Ethiopia’s Unsettled Transition $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ )HEUXDU\ +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Crisis ........................................................................................................... 2 A. Popular Protests and Communal Clashes ................................................................. 3 B. The EPRDF’s Internal Fissures ................................................................................. 6 C. Economic Change and Social Malaise ....................................................................... 8 III. Abiy Ahmed Takes the Reins ............................................................................................ 12 A. A Wider Political Crisis .............................................................................................. 12 B. Abiy’s High-octane Ten Months ................................................................................ 15 IV. Internal Challenges and Opportunities ............................................................................ 21 A. Calming Ethnic and Communal Conflict .................................................................. -

Shambel Meressa Advisor

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project By: Shambel Meressa Advisor: Girmay Kahssay (Dr.) A Thesis submitted to the school of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway project Shambel Meressa A Thesis Submitted to The School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Railway Civil Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2017 Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Civil and Environmental Engineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Shambel Meressa, entitled: “Assessment of potential causes of construction delay in tunnels; a case study at Awash-Weldiya railway project” and submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences (Railway Civil Engineering) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Approved by the Examining Committee: Internal Examiner ___________________________ Signature ___________ Date ___________ External Examiner _________________________ Signature____________ Date ____________ Advisor __________________________________ Signature ___________ Date ____________ _____________________________________________________ School or Center Chair Person Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash- Weldiya Railway Project Declaration I declare that this thesis entitled “Assessment of Potential Causes of Construction Delay in Tunnels; A Case Study at Awash-Weldiya Railway Project” is my original work. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

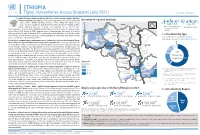

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Hum Ethio Manitar Opia Rian Re Espons E Fund D

Hum anitarian Response Fund Ethiopia OCHA, 2011 OCHA, 2011 Annual Report 2011 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Response Fund – Ethiopia Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents Note from the Humanitarian Coordinator ................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 2011 Humanitarian Context ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Map - 2011 HRF Supported Projects ............................................................................................. 6 2. Information on Contributors ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Donor Contributions to HRF .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Fund Overview .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Summary of HRF Allocations in 2011 ............................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 HRF Allocation by Sector ....................................................................................................... -

Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay Fisheries Assessment Report Mara River Basin, Tanzania

Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay Fisheries Assessment Report Mara River Basin, Tanzania Mkindo River Catchment, Wami RivrBasin, Tanzania |i Integrated Management of Coastal and Freshwater Systems Program Fisheries in Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay Baseline Survey of Fisheries Resources in the Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay Mara River Basin, Tanzania Mara Basin, Tanzania Fisheries in Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay Funding for this publication was provided by the people of the United States of America through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), as a component of the Integrated Management of Coastal and Freshwater Systems Leader with Associates (LWA) Agreement No. EPP-A-00-04-00015-00. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Agency for International Development of the United States Government or Florida International University. Copyright © Global Water for Sustainability Program – Florida International University This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of the publication may be made for resale or for any commercial purposes whatsoever without the prior permission in writing from the Florida International University - Global Water for Sustainability Program. Any inquiries can be addressed to the same at the following address: Global Water for Sustainability Program Florida International University Biscayne Bay Campus 3000 NE 151 St. ACI-267 North Miami, FL 33181 USA Email: [email protected] Website: www.globalwaters.net For bibliographic purposes, this document should be cited as: Baseline Survey of Fisheries Resources in the Mara Swamp and Musoma Bay, Mara6 Basin, Tanzania. -

Ethiopia, the TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Development Center for African Development Policy Research Archives 8-2001 Ethiopia, The TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Milkias, Paulos, "Ethiopia, The TPLF nda Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/4 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETHIOPIA, TPLF AND ROOTS OF THE 2001 * POLITICAL TREMOR ** Paulos Milkias Ph.D. ©2001 Marianopolis College/Concordia University he TPLF has its roots in Marxist oriented Tigray University Students' movement organized at Haile Selassie University in 1974 under the name “Mahber Gesgesti Behere Tigray,” [generally T known by its acronym – MAGEBT, which stands for ‘Progressive Tigray Peoples' Movement’.] 1 The founders claim that even though the movement was tactically designed to be nationalistic it was, strategically, pan-Ethiopian. 2 The primary structural document the movement produced in the late 70’s, however, shows it to be Tigrayan nationalist and not Ethiopian oriented in its content. -

LAKE VICTORIA Commercial Agriculture –Especiallycoffee Andcotton–Are Increasingly Important

© Lonely Planet Publications 240 Lake Victoria LAKE VICTORIA Lake Victoria is Africa’s largest lake, and the second-largest freshwater lake in the world. While the Tanzanian portion sees only a trickle of tourists, the region holds many attractions for those who have a bent for the offbeat and who want to immerse themselves in the rhythms of local life. At the Bujora Cultural Centre near Mwanza, you can learn Sukuma dancing and get acquainted with the culture of Tanzania’s largest tribal group. Further north at Butiama is the Nyerere museum, an essential stop for anyone interested in the great statesman. Musoma and Bukoba – both with a sleepy, waterside charm – are ideal places for getting a taste of lakeshore life. Bukoba is also notable as the heartland of the Haya people, who had one of the most highly developed early societies on the continent. Mwanza, to the southeast, is Tanzania’s second largest city after Dar es Salaam, and an increasingly popular jumping off point for safaris into the Serengeti’s Western Corridor. To the southwest is Rubondo Island National Park for bird-watching and relaxing. The best way to explore the lake region is as part of a larger loop combining Uganda and/or Kenya with Tanzania’s northern circuit via the western Serengeti, although you’ll need time, and a tolerance for rough roads. While most accommodation is no-frills, there are a few idyllic getaways – notably on Rubondo and Lukuba Islands, and near Mwanza. Most locals you’ll meet rely on fishing and small-scale farming for their living, although industry and commercial agriculture – especially coffee and cotton – are increasingly important. -

Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours the Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia

Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4 Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant September 1994 Please send comments on this paper to: Relief and Rehabilitation Network Overseas Development Institute Regent's College Inner Circle Regent's Park London NW1 4NS United Kingdom A copy will be sent to the author. Comments received may be used in future Newsletters. ISSN: 1353-8691 © Overseas Development Institute, London, 1994. Photocopies of all or part of this publication may be made providing that the source is acknowledged. Requests for commercial reproduction of Network material should be directed to ODI as copyright holders. The Network Coordinator would appreciate receiving details of any use of this material in training, research or programme design, implementation or evaluation. Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant1 Contents Page Maps 1. Introduction 1 2. Pride and Prejudice in the Somali Region 5 : The Political History of a Conflict 3 * The Ethiopian empire-state and the colonial powers 4 * Greater Somalia, Britain and the growth of Somali nationalism 8 * Conflict and war between Ethiopia and Somalia 10 * Civil war in Somalia 11 * The Transitional Government in Ethiopia and Somali Region 5 13 3. Cycles of Relief and Rehabilitation in Eastern Ethiopia : 1973-93 20 * 1973-85 : `Relief shelters' or the politics of drought and repatriation 21 * 1985-93 : Repatriation as opportunity for rehabilitation and development 22 * The pastoral sector : Recovery or control? 24 * Irrigation schemes : Ownership, management and economic viability 30 * Food aid : Targeting, free food and economic uses of food aid 35 * Community participation and institutional strengthening 42 1 Koenraad Van Brabant has been project manager relief and rehabilitation for eastern Ethiopia with SCF(UK) and is currently Oxfam's country representative in Sri Lanka. -

Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST in ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE

Mekelle Invest in Ethiopia: Focus MEKELLE December 2012 INVEST IN ETHIOPIA: FOCUS MEKELLE December 2012 Millennium Cities Initiative, The Earth Institute Columbia University New York, 2012 DISCLAIMER This publication is for informational This publication does not constitute an purposes only and is meant to be purely offer, solicitation, or recommendation for educational. While our objective is to the sale or purchase of any security, provide useful, general information, product, or service. Information, opinions the Millennium Cities Initiative and other and views contained in this publication participants to this publication make no should not be treated as investment, representations or assurances as to the tax or legal advice. Before making any accuracy, completeness, or timeliness decision or taking any action, you should of the information. The information is consult a professional advisor who has provided without warranty of any kind, been informed of all facts relevant to express or implied. your particular circumstances. Invest in Ethiopia: Focus Mekelle © Columbia University, 2012. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. ii PREFACE Ethiopia, along with 189 other countries, The challenges that potential investors adopted the Millennium Declaration in would face are described along with the 2000, which set out the millennium devel- opportunities they may be missing if they opment goals (MDGs) to be achieved by ignore Mekelle. 2015. The MDG process is spearheaded in Ethiopia by the Ministry of Finance and The Guide is intended to make Mekelle Economic Development. and what Mekelle has to offer better known to investors worldwide. Although This Guide is part of the Millennium effort we have had the foreign investor primarily and was prepared by the Millennium Cities in mind, we believe that the Guide will be Initiative (MCI), which is an initiative of of use to domestic investors in Ethiopia as The Earth Institute at Columbia University, well. -

Ethiopia – Flooding Flash Update 3

Ethiopia – Flooding Flash Update 3 22 May 2018 On 21 May, the National Disaster Risk Management Commission (NDRMC)-led Flood Task Force issued a revised Flood Alert1, based on the monthly National Meteorology Agency (NMA) forecast for the month of May 2018. The latest NMA forecast informs of a shift of the heavy rainfall from south eastern Ethiopia (mainly Somali region) to the central, western and parts of northern Ethiopia, including Afar, Amhara, Gambella, southern Oromia, parts of SNNP and Tigray region. Accordingly, average to above average rainfall is expected in Zones 3, 4 and 5 of Afar region; North and South Wello, North and South Gonder, Bahir Dar Zuria, Western and Eastern Gojam, and Awi zones of Amhara region; Benishan- gul Gumuz region; Gambella region; Harari region; Arsi, Bale, Borena, Guji, eastern, northern and western Shewa, East and West Hararge zones of Oromia region; most zones of SNNPR; most of Somali region; Tigray region; as well as Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa cities. The rains are expected to benefit agricultural activities by improving moisture forbelg and long cycle meher crops and perennial plants; and to help pasture regeneration and water source replenishment. However, flash floods are anticipated in areas along river banks and areas with low soil water percolation capacity. The first Alert was issued on 27 April following the reactivation of the National Flood Task Force on 19 April, to co- ordinate flood mitigation, preparedness and response efforts. Another revision will be conducted based on NMA’s forecast for the 2018 summer kiremt rains and new developments on the ground. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. LXVII-No. 56 NAIROBI, 7th December 1965 Price: Sh. 1 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES SUPPLEMENT No. 94 PAGE Bills, 1965 Appointments ,. ,, .. ., .. 1452 The Interpretalion and General Provisions Act- Temporary Transfer of Powers . SUPPLEMENT No. 95 The Food, Drugs and Chemical Substances Act, Legislative Supplement 1965-Appointments . LEGALNOTICE NO. PAGE The Agriculture Acl-Appointments, etc. 1452, 321-The Co~lstitution (Amendment of Laws) 1 (Marketing of Agricultural Produce) The Valuation of Crown Lands Rules, 1960- Order, 1965 . Appointment . 322-The Protected Areas (No. 2) Order, 1965 . The Local Government Regulations, 1963-Appoint- 323-The Protected Areas (No. 3) Order, 1965 . ment . 324-The Price Control (Sifted Maizemeal) (Amend- The Traffic Act-Appointments . ment) (No. 2) Order, 1965 . The Mombasa Pipeline Board Act-Appointments . 325-The Price Control (Maize and Maizemeal) The Forests Act-Declarations . (Amendment) (No. 3) Order, 1965 . 326-The Customs Tariff (Remission) (No. 9) Order, The Land Adjudication Act-Notification . 1965 . The General Local Loans Act . 327-The Customs Tariff (Remission) (No. 10) The Tax Reserve Certificates Act-Lost Certificates . Order, 1965 . .. Law Examination for Administrative Officers-Date . 328-The Local Industries (Refund of Customs The Trout Act-Appointment Duties) (Short-term) (Amendment) (No. 3) . Order, 1965 .. .. .. 569 The Constitution of Kenya-Appointment . 329-The Local Industries (Refund of Customs The African Courts Act- Duties) (Long-term) (Amendment) (No. 4) Appointment, etc. .. .. .. .. .. Order, 1965 . .. 569 Sessions of Court of Review . 330-The Children and Young Persons (Appointed The East African Licensing of Air Services Regulations, Local Authority) (No.