Avhandling. Tryckversion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

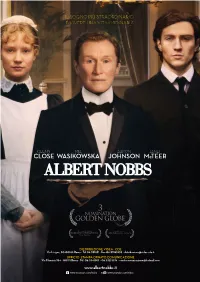

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-Like Authors in Irish Fiction: the Case of John Banville

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-like Authors in Irish Fiction: The Case of John Banville Roberta Gefter Wondrich University of Trieste Abstract This article aims at exploring the crucial correlation between love (erosldesire) and writing, death and writing and God-like authorial strategies as a relevant feature of postmodernist fiction mainly as it unfolds in the work of Ireland's most important (postmodernist) novelist, John Banville. This issue is highly relevant in the context of postmodernism as, according to Brian McHale, postmodern fiction has thoroughly exploited both love and death not only as topics but essentially as formally relevant features of the novel, by systematically foregrounding the relation existing between author, characters and reader, al1 entangled in a web of love, seduction and deferred annihilation, and by transgressing the related ontological boundaries. In this regard, then, Banville's novels (notably the 'tetralogy of art', narnely The Book ofEvidence (1989), Ghosts (1993), Athena (1995) and The Untouchable (1998)) thoroughly explore and foregromd-probably for the first time in Irish writing-both the notion of love and desire as a creative activity, of textual narrative as necessarily seductive and, finally, the time-hoiioured equation of life with discourse/narration, thus recalling the problematic motif of the impossibility and necessity of discourse. In the context of Irish fiction, postmodernist literary strategies have not been practised too extensively in the last decades, while it is by now widely acknowledged that a great many of the main features of postmodernist writing had already been inaugurated by the titans of the protean Irish 'modernism': 1 am obviously thinking of Joyce-especially in Finnegan S Wake-and Flann O'Brien. -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997). -

Reflecting on Discovering John Banville As a Young Reader Refletindo a Minha Descoberta De John Banville Como Jovem Leitor

ABEI Journal — The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v.22, n.1, 2020, p. 45-47 Reflecting on Discovering John Banville as a Young Reader Refletindo a Minha Descoberta de John Banville como Jovem Leitor Billy O’Callaghan When it comes to the crafting of a story or a novel, every writer will profess – or at least claim – a meticulous weighing of their sentences, but few that I can think of, in Ireland or anywhere, carry to their work anything like the dexterity, imaginative intellect and general broad-spectrum genius employed by John Banville. What's the difference between him and the rest of us? We all have the same dictionary’s worth of words at our disposal, but what is it about the particular way he uses them that sets him so apart? For one thing, I suppose, there is the rare symphonic quality to his language, the words on the page, often simple enough in and of themselves, somehow stir to life by a complexly structured natural musicality when strung together in their precise way. Can that be learned? I'm not sure. Found, possibly, more so than learned, or self-taught, by long trial-and-error struggle, honing the mind's ear through a deep and careful attention to some internal tuning fork, and pushing far beyond the poetic, refusing to settle for merely that, out into the realms of sorcery. Because his sentences always seem just right, even when they have you in their highest moments breathing in gasps, the temptation – and surely the mistake – would be to think that any of it comes easily. -

The Quest for God in the Novels of John Banville 1973-2005: a Postmodern Spiritualily

THE QUEST FOR GOD IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN BANVILLE 1973-2005: A POSTMODERN SPIRITUALITY Brendan McNamee Lewiston, Queenson, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. 2006 (by Violeta Delgado Crespo. Universidad de Zaragoza) [email protected] 121 As McNamee puts it in his study, it seems that “the ultimate aim of Banville’s fiction is to elude interpretation” (6). It is perhaps this elusiveness that ensures a growing number of critical contributions on the work of a writer who has explicated his aesthetic, his view of art in general, and literature in particular, in talks, interviews and varied writings. McNamee’s is the seventh monographic study of John Banville’s work published to date, and claims to differ from the previous six by widening the cultural context in which the work of the Irish writer has been read. Although, to my knowledge, John Banville has never defined himself in these terms, McNamee portrays him as an essentially religious writer (13) when he foregrounds the deep spiritual yearning that Banville’s fiction exhibits in combination with the many postmodern elements (paradox and parody, self- reflexivity, intertextuality) that are familiar in his novels. To McNamee, Banville’s enigmatic fictions allow for a link between the disparate phenomena of pre-modern mysticism and postmodernism, suggesting that many aspects of the postmodern sensibility veer toward the spiritual. He considers the language of Banville’s fiction intrinsically mystical, an artistic form of what is known as apophatic language, which he defines as “the mode of writing with which mystics attempt to say the unsayable” (170). In terms of style, Banville’s writing approaches the ineffable: that which cannot be paraphrased or described. -

“The Ghost of That Ineluctable Past”: Trauma and Memory in John Banville’S Frames Trilogy GPA: 3.9

“THE GHOST OF THAT INELUCTABLE PAST”: TRAUMA AND MEMORY IN JOHN BANVILLE’S FRAMES TRILOGY BY SCOTT JOSEPH BERRY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December, 2016 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Jefferson Holdridge, PhD, Advisor Barry Maine, PhD, Chair Philip Kuberski, PhD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To paraphrase John Banville, this finished thesis is the record of its own gestation and birth. As such, what follows represents an intensely personal, creative journey for me, one that would not have been possible without the love and support of some very important people in my life. First and foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Kelly, for all of her love, patience, and unflinching confidence in me throughout this entire process. It brings me such pride—not to mention great relief—to be able to show her this work in its completion. I would also like to thank my parents, Stephen and Cathyann Berry, for their wisdom, generosity, and support of my every endeavor. I am very grateful to Jefferson Holdridge, Omaar Hena, Mary Burgess-Smyth, and Kevin Whelan for their encouragement, mentorship, and friendship across many years of study. And to all of my Wake Forest friends and colleagues—you know who you are—thank you for your companionship on this journey. Finally, to Maeve, Nora, and Sheilagh: Daddy finally finished his book. Let’s go play. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv -

John Banville's Path From

ABEI Journal — The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v.22, n.1, 2020, p. 135-146 “Cancel, yes, cancel, and begin again”: John Banville’s Path from ‘Einstein’ to Mefisto “Cancele, sim, cancele e comece de novo”: O Caminho de John Banville de ‘Einstein’ a Mefisto Kersti Tarien Powell Abstract: Focusing on unpublished manuscript materials, this article is the first scholarly attempt to investigate the textual and thematic evolution of John Banville’s Mefisto (1986). As originally conceived, Mefisto would loosely follow Albert Einstein’s life story in order to investigate the moral and political undercurrents of 20th-century European weltanchauung. However, the novel’s five-year-long composition process culminates with the eradication of these historical, moral and scientific concerns. Mefisto is finally born when Banville establishes Gabriel Swan’s narrative voice. As this article argues, this novel constitutes a turning point not only for the science tetralogy but for Banville’s literary career. Keywords: Mefisto; literary manuscripts; narrative voice; Albert Einstein; science and literature. Resumo: Com foco em manuscritos não publicados, este artigo é a primeira tentativa acadêmica de investigar a evolução textual e temática de Mefisto (1986), de John Banville. Como originalmente concebido, a história de Mefisto seria livremente baseada na vida de Albert Einstein, a fim de investigar as correntes morais e políticas da weltanchauung europeia do século XX. No entanto, o processo de cinco anos de composição do romance culmina com a erradicação dessas preocupações históricas, morais e científicas. Mefisto finalmente nasceu quando Banville estabelece a voz narrativa de Gabriel Swan. Como este artigo argumenta, este romance constitui um ponto de virada não apenas para a tetralogia científica, mas também para a carreira literária de Banville. -

May, Talitha 01-27-18

Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Talitha May May 2018 © 2018 Talitha May. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World by TALITHA MAY has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Sherrie L. Gradin Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT MAY, TALITHA, Ph.D., May 2018, English Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World Director of Dissertation: Sherrie L. Gradin Beset with political, social, economic, cultural, and environmental degradation, along with the imminent threat of nuclear war, the world might be at its end. Building upon Richard Miller’s inquiry from Writing at the End of the World, this dissertation investigates if it is “possible to produce [and teach] writing that generates a greater connection to the world and its inhabitants.” I take up Paul Lynch’s notion of the apocalyptic turn and suggest that when writers Kurt Spellmeyer, Richard Miller, Derek Owens, Robert Yagelski, Lynn Worsham, and Ann Cvetkovich confront disaster, they reach an impasse whereby they begin to question disciplinary assumptions such as critique and pose inventive ways to think about writing and writing pedagogy that emphasize the notion and practice of connecting to the everyday. Questioning the familiar and cultivating what Jane Bennett terms “sensuous enchantment with everyday” are ethical responses to the apocalypse; nonetheless, I argue that disasters and death master narratives will continually resurface if we think that an apocalyptic mindset can fully account for the complexity and irreducibility of lived experience. -

The Broken Jug (1994), John Banville S

Anna Fattori (Rome) “A Genuinely Funny German Farce” Turns into a Very Irish Play: The Broken Jug (1994), John Banvilles Adaptation of Heinrich von Kleists Der zerbrochne Krug (1807) John Banvilles concern with national cultures different from his own, es- pecially with German-speaking literature, has been widely analysed.1 Ref- erences to German culture are scattered throughout his writings. Some- times they are semi-quotations or direct quotations, like for example the Wittgensteinian sentence “whereof I cannot speak, thereof I must be silent”2 at the end of Birchwood (1973), which is the epistemological counterpart to the philosophical opening statement “I am, therefore I think”,3 the reversal of the Cartesian dictum cogito, ergo sum; more fre- quently they are ethereal and implicit allusions which create an intriguing pattern of intertextuality and challenge the reader to find out the fore- texts for the clues given. For both open and hidden indebtedness to for- eign cultures and to German culture in particular, The Newton Letter 1 See Rdiger Imhof, “German Influences on John Banville and Aidan Higgins,” in Literary Interrelations. Ireland, England and the World. Vol. 2. Comparison and Impact, eds. Wolfgang Zach and Heinz Kosok (Tbingen: Narr, 1987), 335–347; Id., John Banville. A Critical Study (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1989); Gordon J. A. Burgess, “An Irish Die Wahlverwandtschaften,”inGerman Life and Letters 45 (1992): 140–148; Joseph Swann, “Banvilles Faust: Doctor Copernicus, Kepler, The Newton Letter and Mefisto as Stories of the European Mind,” in A Small Nations Contribution to the World. Essays on Anglo-Irish Lit- erature and Language, eds. -

HH Dissertation Final (Redacted)

Heidegger’s hesitations: Mise-en-scenes of unreliable narration. Nicholas H. Waddell ORCHID ID No: 0000-0002-5766-1032 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February, 2020. VCA Art Faculty of Fine Arts and Music The University of Melbourne 1 Abstract Modern Australian identity is impacted by historically romanticised images and narratives of the occident which in post-colonial Australia remain oddly familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. This research explores certain romanticised narratives as the question of their reliability becomes the catalyst for a collision between art, lived- experience, identity and representation. ‘Heidegger’s hesitations: Mise-en-scenes of unreliable narration’ examines this concern primarily through interrogating the effects of this collision. As a figure of substantial philosophical consequence whose ideas have significantly informed art theory, Heidegger and his Greek sojourn is pursued through the retracing as being experientially-unanalysed. If ‘retracing’ is the ‘way of the image’, what if anything, can be specifically recuperated from retracing philosopher Martin Heidegger’s 1962 sojourn across Greece that might inform art today? In the European Spring of 2017, the project of retracing followed Heidegger’s journey to Greece uncovering a series of points which provided the basis for a critique of his concept of alétheia. Tourism emerged as a practical method for exploring certain narratives. Metaphorically, tourism provided a useful image for the exploration of ideas. For the tourist, a dislocation occurs that characterises an un-belonging. It is this sense of un-belonging that is apparent in the many hesitations Heidegger recalls in his narrative account ‘Sojourns: The journey to Greece’. -

GENRE and CODE in the WORK of JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle

GENRE AND CODE IN THE WORK OF JOHN BANVILLE Kevin Boyle St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra Dublin City University School of Humanities Department of English Supervisor: Dr Derek Hand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD April 2016 I hereby certify that this material, which T now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_____________________________ ID No.: 59267054_______ Date: Table of contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction: Genre and the Intertcxlual aspects of Banville's writing 5 The Problem of Genre 7 Genre Theory 12 Transgenerie Approach 15 Genre and Post-modernity' 17 Chapter One: The Benjamin Black Project: Writing a Writer 25 Embracing Genre Fiction 26 Deflecting Criticism from Oneself to One Self 29 Banville on Black 35 The Crossover Between Pseudonymous Authorial Sell'and Characters 38 The Opposition of Art and Craft 43 Change of Direction 45 Corpus and Continuity 47 Personae Therapy 51 Screen and Page 59 Benjamin Black and Ireland 62 Guilt and Satisfaction 71 Real Individuals in the Black Novels 75 Allusions and Genre Awareness 78 Knowledge and Detecting 82 Chapter Two: Doctor Copernicus, Historical Fiction and Post-modernity: