“The Ghost of That Ineluctable Past”: Trauma and Memory in John Banville’S Frames Trilogy GPA: 3.9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Light Free Download

ANCIENT LIGHT FREE DOWNLOAD John Banville | 272 pages | 28 Mar 2013 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780241955406 | English | London, United Kingdom How Light Works By the 17th century, some prominent European scientists began to think differently about light. Start a Wiki. This gracefully written sequel to Golden Witchbreed powerfully depicts the impact of a high-technology civilization on a decaying planet. Davis, Howard. While not on Ancient Light level of The Infinities or The Sea, Ancient Light has one of the most devastatingly beautiful concluding passage of any work of literature I've come across. The Guardian. Helpful Share. This is the sequel to Golden Witchbreed which brought an ambassador to the planet Orthe. Memory of Mrs Gray, summer or rather spring goddes, it was April then, his youthful love. Hidden categories: All stub articles. Log in to get trip updates and message other travelers. She has recently lost her father. Banville is famous for his poetic prose style and in the first 15 pages or so, before the story really takes off, it almost put me off reading, because it felt Ancient Light Fine Style for the sake of it. Anja and Tempus have a wonderful Ancient Light and are super friendly! As with Michael Moorcock's series Ancient Light his anti-heroic Jerry Cornelius, Gentle's sequence retains some basic facts about her two protagonists Valentine also known as the White Crow and Casaubon while changing much else about them, including what world they Ancient Light. Thanks for telling us about the problem. My misgivings about Ancient Light "I this" and "I that" tiresomeness aside. -

"Et in Arcadia Ille – This One Is/Was Also in Arcadia"

99 BARBARA PUSCHMANN-NALENZ "Et in Arcadia ille – this one is/was also in Arcadia:" Human Life and Death as Comedy for the Immortals in John Banville's The Infinities Hermes the messenger of the gods quotes this slightly altered Latin motto (Banville 2009, 143). The original phrase, based on a quotation from Virgil, reads "et in Arcadia ego" and became known as the title of a painting by Nicolas Poussin (1637/38) entitled "The Arcadian Shepherds," in which the rustics mentioned in the title stumble across a tomb in a pastoral landscape. The iconography of a baroque memento mori had been followed even more graphically in an earlier picture by Giovanni Barbieri, which shows a skull discovered by two astonished shepherds. In its initial wording the quotation from Virgil also appears as a prefix in Goethe's autobiographical Italienische Reise (1813-17) as well as in Evelyn Waugh's country- house novel Brideshead Revisited (1945). The fictive first-person speaker of the Latin phrase is usually interpreted as Death himself ("even in Arcadia, there am I"), but the paintings' inscription may also refer to the man whose mortal remains in an idyllic countryside remind the spectator of his own inevitable fate ("I also was in Arcadia"). The intermediality and equivocacy of the motto are continued in The Infinities.1 The reviewer in The Guardian ignores the unique characteristics of this book, Banville's first literary novel after his prize-winning The Sea, when he maintains that "it serves as a kind of catalogue of his favourite themes and props" (Tayler 2009). -

John Banville's New Novel Ancient Light

FREE JULY 2012 Readings Monthly Alice Pung on Majok Tulba • Nick Earls EE REVIEW P.7 EE REVIEW P.7 S . ANCIENT LIGHT IMAGE: DETAIL FROM COVER OF JOHN BANVILLE'S IMAGE: DETAIL John Banville’s new novel Ancient Light July book, CD & DVD new releases. More new releases inside. FICTION AUS FICTION BIOGRAPHY AUS FICTION KIDS DVD POP CLASSICAL $32.99 $19.95 e $16.82 $29.95 $24.95 $24.95 $39.95 b $49.95 $19.95 $26.95 $21.95 >> p7 >> p5 >> p11 >> p5 >> p15 >> p17 >> p18 >> p19 July event highlights : Ita Buttrose at Cinema Nova; Kylie Kwong at Hawthorn; Simone Felice & Josh Ritter at Carlton. More inside. All shops open 7 days, except the State Library shop which is open Monday – Saturday, and the Brain Centre shop which is open Monday – Friday. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 Readings at the Brain Centre, Parkville 30 Royal Parade 9347 1749 See more new books, music and film, read news and reviews, check event details, and browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au FIRST GLANCE PROGRAM AND PASSES ONLINE NOW 2 Readings Monthly July 2012 From the Books Desk Mark’s Say By the time you read this column, the News and views from Readings’ managing Miles Franklin prize will have been awarded This Month’s News director Mark Rubbo VISIT THE MELBOURNE MIFF for 2012. -

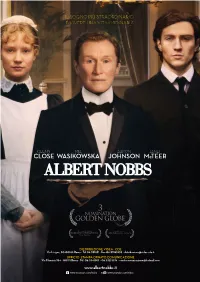

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-Like Authors in Irish Fiction: the Case of John Banville

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-like Authors in Irish Fiction: The Case of John Banville Roberta Gefter Wondrich University of Trieste Abstract This article aims at exploring the crucial correlation between love (erosldesire) and writing, death and writing and God-like authorial strategies as a relevant feature of postmodernist fiction mainly as it unfolds in the work of Ireland's most important (postmodernist) novelist, John Banville. This issue is highly relevant in the context of postmodernism as, according to Brian McHale, postmodern fiction has thoroughly exploited both love and death not only as topics but essentially as formally relevant features of the novel, by systematically foregrounding the relation existing between author, characters and reader, al1 entangled in a web of love, seduction and deferred annihilation, and by transgressing the related ontological boundaries. In this regard, then, Banville's novels (notably the 'tetralogy of art', narnely The Book ofEvidence (1989), Ghosts (1993), Athena (1995) and The Untouchable (1998)) thoroughly explore and foregromd-probably for the first time in Irish writing-both the notion of love and desire as a creative activity, of textual narrative as necessarily seductive and, finally, the time-hoiioured equation of life with discourse/narration, thus recalling the problematic motif of the impossibility and necessity of discourse. In the context of Irish fiction, postmodernist literary strategies have not been practised too extensively in the last decades, while it is by now widely acknowledged that a great many of the main features of postmodernist writing had already been inaugurated by the titans of the protean Irish 'modernism': 1 am obviously thinking of Joyce-especially in Finnegan S Wake-and Flann O'Brien. -

The Image of Man in Metafictional Novels by John Banville: Celebrating the Power of the Imagination

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LXI, zeszyt 5 – 2013 MACIEJ CZERNIAKOWSKI * THE IMAGE OF MAN IN METAFICTIONAL NOVELS BY JOHN BANVILLE: CELEBRATING THE POWER OF THE IMAGINATION A b s t r a c t. THe essay analyzes How JoHn Banville reconstructs tHe image of man in His two novels Kepler and Doctor Copernicus by means of broadly understood metafiction. The Author of tHe essay discusses tHe following elements: implied autHor’s and narrator’s power of creative imagination and RHeticus’s self-consciousness wHicH enables to create fiction and intertextuality of tHe novel. WHen analyzing tHe last aspect of tHe novels, tHe AutHor mentions also MicHel Foucault’s term, Heterotopia. THe results of tHis analysis are twofold. On tHe one Hand, man Has got practically unlimited creative imagination on tHeir part. On tHe otHer Hand, man seems to be lost in tHe world of unclear ontological boundaries, wHicH proves a paradoxical image of man. In tHe critical works approacHing Doctor Copernicus and Kepler as metafictions, tHat is “fictional writing wHicH self-consciously and systematically draws atten- tion to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about tHe relationsHip between fiction and reality” (2), critics most often comment on tHese two novels in a fairly general way. For instance, Eve Patten explains tHat “[m]etafictional and pHilosopHical writing in Ireland continues to be dominated . by JoHn Banville (b. 1945). Since tHe mid1980s, Banville’s fiction Has continued its analysis of alternative languages and structures of perception” (272). JosepH McMinn also concentrates on language, claiming tHat it “is largely self-referential and simply cannot contain or explain tHe world outside itself, tHis body of work belongs firmly in tHe international context of postmodernism, botH stylistically and pHilo- sopHically” (“Versions of Banville” 87). -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997). -

Reflecting on Discovering John Banville As a Young Reader Refletindo a Minha Descoberta De John Banville Como Jovem Leitor

ABEI Journal — The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v.22, n.1, 2020, p. 45-47 Reflecting on Discovering John Banville as a Young Reader Refletindo a Minha Descoberta de John Banville como Jovem Leitor Billy O’Callaghan When it comes to the crafting of a story or a novel, every writer will profess – or at least claim – a meticulous weighing of their sentences, but few that I can think of, in Ireland or anywhere, carry to their work anything like the dexterity, imaginative intellect and general broad-spectrum genius employed by John Banville. What's the difference between him and the rest of us? We all have the same dictionary’s worth of words at our disposal, but what is it about the particular way he uses them that sets him so apart? For one thing, I suppose, there is the rare symphonic quality to his language, the words on the page, often simple enough in and of themselves, somehow stir to life by a complexly structured natural musicality when strung together in their precise way. Can that be learned? I'm not sure. Found, possibly, more so than learned, or self-taught, by long trial-and-error struggle, honing the mind's ear through a deep and careful attention to some internal tuning fork, and pushing far beyond the poetic, refusing to settle for merely that, out into the realms of sorcery. Because his sentences always seem just right, even when they have you in their highest moments breathing in gasps, the temptation – and surely the mistake – would be to think that any of it comes easily. -

The Quest for God in the Novels of John Banville 1973-2005: a Postmodern Spiritualily

THE QUEST FOR GOD IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN BANVILLE 1973-2005: A POSTMODERN SPIRITUALITY Brendan McNamee Lewiston, Queenson, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. 2006 (by Violeta Delgado Crespo. Universidad de Zaragoza) [email protected] 121 As McNamee puts it in his study, it seems that “the ultimate aim of Banville’s fiction is to elude interpretation” (6). It is perhaps this elusiveness that ensures a growing number of critical contributions on the work of a writer who has explicated his aesthetic, his view of art in general, and literature in particular, in talks, interviews and varied writings. McNamee’s is the seventh monographic study of John Banville’s work published to date, and claims to differ from the previous six by widening the cultural context in which the work of the Irish writer has been read. Although, to my knowledge, John Banville has never defined himself in these terms, McNamee portrays him as an essentially religious writer (13) when he foregrounds the deep spiritual yearning that Banville’s fiction exhibits in combination with the many postmodern elements (paradox and parody, self- reflexivity, intertextuality) that are familiar in his novels. To McNamee, Banville’s enigmatic fictions allow for a link between the disparate phenomena of pre-modern mysticism and postmodernism, suggesting that many aspects of the postmodern sensibility veer toward the spiritual. He considers the language of Banville’s fiction intrinsically mystical, an artistic form of what is known as apophatic language, which he defines as “the mode of writing with which mystics attempt to say the unsayable” (170). In terms of style, Banville’s writing approaches the ineffable: that which cannot be paraphrased or described. -

Number 24 the ‘B’ Issue

Five Dials Number 24 The ‘B’ Issue Amy LeAch 5 On Pandas and Bamboo JohN Banville 7 On Beginnings, Middles, Ends bridget o’connor 10 Three Stories . plus bear illustrations like you won’t believe. CONTRIBUTORS Banville, JohN: Born in Wexford, Ireland, in 1945. Books include The Book of Evidence, The Untouchable, and his most recent novel, Ancient Light. Man Booker Prize winner in 2005 for The Sea. becky BarNicoAt draws comics for The Stool Pigeon and also her blog everyoneisherealready.blogspot.com. By day she is the commissioning editor on Guardian Weekend. She lives in London. Blackpool raised, born in Liverpool, Neal JoNes studied Fine Art in Canterbury before packing it in to live aboard a 1920s wooden pinnace, travel Britain in a van and survive on DIY and gardening work. He returned to art via a year at The Prince’s Drawing School, becom- ing a John Moores prizewinner soon after. He now paints and gardens daily on his vegetable allotment garden in North London. Before recently moving to Montana, Amy LeAch lived in Chicago. Her book, Things That Are: Encounters with Plants, Stars and Animals, will be published by Canongate in June, 2013. bridget o’connor is the author of two collections of stories, Here Comes John and Tell Her You Love Her. She won the 1991 Time Out short story prize. Her play, The Flags, was staged at the Manchester Royal Exchange and her screenplay for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which she co-wrote with her husband, Peter Straughan, was filmed by Tomas Alfredson and released in 2011. -

May, Talitha 01-27-18

Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Talitha May May 2018 © 2018 Talitha May. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World by TALITHA MAY has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Sherrie L. Gradin Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT MAY, TALITHA, Ph.D., May 2018, English Writing the Apocalypse: Pedagogy at the End of the World Director of Dissertation: Sherrie L. Gradin Beset with political, social, economic, cultural, and environmental degradation, along with the imminent threat of nuclear war, the world might be at its end. Building upon Richard Miller’s inquiry from Writing at the End of the World, this dissertation investigates if it is “possible to produce [and teach] writing that generates a greater connection to the world and its inhabitants.” I take up Paul Lynch’s notion of the apocalyptic turn and suggest that when writers Kurt Spellmeyer, Richard Miller, Derek Owens, Robert Yagelski, Lynn Worsham, and Ann Cvetkovich confront disaster, they reach an impasse whereby they begin to question disciplinary assumptions such as critique and pose inventive ways to think about writing and writing pedagogy that emphasize the notion and practice of connecting to the everyday. Questioning the familiar and cultivating what Jane Bennett terms “sensuous enchantment with everyday” are ethical responses to the apocalypse; nonetheless, I argue that disasters and death master narratives will continually resurface if we think that an apocalyptic mindset can fully account for the complexity and irreducibility of lived experience.