Beckettian Irony in the Work of Paul Auster, John Banville and J.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Light Free Download

ANCIENT LIGHT FREE DOWNLOAD John Banville | 272 pages | 28 Mar 2013 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780241955406 | English | London, United Kingdom How Light Works By the 17th century, some prominent European scientists began to think differently about light. Start a Wiki. This gracefully written sequel to Golden Witchbreed powerfully depicts the impact of a high-technology civilization on a decaying planet. Davis, Howard. While not on Ancient Light level of The Infinities or The Sea, Ancient Light has one of the most devastatingly beautiful concluding passage of any work of literature I've come across. The Guardian. Helpful Share. This is the sequel to Golden Witchbreed which brought an ambassador to the planet Orthe. Memory of Mrs Gray, summer or rather spring goddes, it was April then, his youthful love. Hidden categories: All stub articles. Log in to get trip updates and message other travelers. She has recently lost her father. Banville is famous for his poetic prose style and in the first 15 pages or so, before the story really takes off, it almost put me off reading, because it felt Ancient Light Fine Style for the sake of it. Anja and Tempus have a wonderful Ancient Light and are super friendly! As with Michael Moorcock's series Ancient Light his anti-heroic Jerry Cornelius, Gentle's sequence retains some basic facts about her two protagonists Valentine also known as the White Crow and Casaubon while changing much else about them, including what world they Ancient Light. Thanks for telling us about the problem. My misgivings about Ancient Light "I this" and "I that" tiresomeness aside. -

"Et in Arcadia Ille – This One Is/Was Also in Arcadia"

99 BARBARA PUSCHMANN-NALENZ "Et in Arcadia ille – this one is/was also in Arcadia:" Human Life and Death as Comedy for the Immortals in John Banville's The Infinities Hermes the messenger of the gods quotes this slightly altered Latin motto (Banville 2009, 143). The original phrase, based on a quotation from Virgil, reads "et in Arcadia ego" and became known as the title of a painting by Nicolas Poussin (1637/38) entitled "The Arcadian Shepherds," in which the rustics mentioned in the title stumble across a tomb in a pastoral landscape. The iconography of a baroque memento mori had been followed even more graphically in an earlier picture by Giovanni Barbieri, which shows a skull discovered by two astonished shepherds. In its initial wording the quotation from Virgil also appears as a prefix in Goethe's autobiographical Italienische Reise (1813-17) as well as in Evelyn Waugh's country- house novel Brideshead Revisited (1945). The fictive first-person speaker of the Latin phrase is usually interpreted as Death himself ("even in Arcadia, there am I"), but the paintings' inscription may also refer to the man whose mortal remains in an idyllic countryside remind the spectator of his own inevitable fate ("I also was in Arcadia"). The intermediality and equivocacy of the motto are continued in The Infinities.1 The reviewer in The Guardian ignores the unique characteristics of this book, Banville's first literary novel after his prize-winning The Sea, when he maintains that "it serves as a kind of catalogue of his favourite themes and props" (Tayler 2009). -

Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel BA, Trinity

Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Katharine Bubel, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Nicholas Bradley, Department of English Supervisor Dr. Magdalena Kay, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Iain Higgins, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Tim Lilburn, Department of Writing Outside Member iii Abstract "Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices” focusses on the intersection of the environmental and religious imaginations in the work of five West Coast poets: Robinson Jeffers, Theodore Roethke, Robert Hass, Denise Levertov, and Jan Zwicky. My research examines the selected poems for their reimagination of the sacred perceived through attachments to particular places. For these writers, poetry is a constitutive practice, part of a way of life that includes desire for wise participation in the more-than-human community. Taking into account the poets’ critical reflections and historical-cultural contexts, along with a range of critical and philosophical sources, the poetry is examined as a discursive spiritual exercise. It is seen as conjoined with other focal practices of place, notably meditative walking and attentive looking and listening under the influence of ecospiritual eros. -

The ESSE Messenger

The ESSE Messenger A Publication of ESSE (The European Society for the Study of English Vol. 26-2 Winter 2017 ISSN 2518-3567 All material published in the ESSE Messenger is © Copyright of ESSE and of individual contributors, unless otherwise stated. Requests for permissions to reproduce such material should be addressed to the Editor. Editor: Dr. Adrian Radu Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Faculty of Letters Department of English Str. Horea nr. 31 400202 Cluj-Napoca Romania Email address: [email protected] Cover illustration: Jane Austen’s Reading Nook at Chawton House Picture credit: Alexandru Paul Margau Contents Jane Austen Ours 5 Bringing the Young Ladies Out Carmen María Fernández Rodríguez 5 Understanding Jane Austen Miguel Ángel Jordán Enamorado 18 A Historical Reflection on Jane Austen’s Popularity in Spain Isis Herrero López 27 Authorial Realism or how I Learned that Jane Was a Person Alexandru Paul Mărgău 40 Adaptations, Sequels and Success Anette Svensson 46 Reviews 59 Herrero, Dolores and Sonia Baelo-Allue (eds.), The Splintered Glass: Facets of Trauma in the Post-Colony and Beyond. Cross Cultures 136. (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2011). Irene Visser 59 Nancy Ellen Batty, The Ring of Recollection: Transgenerational Haunting in the Novels of Shashi Deshpande (New York: Amsterdam, 2010). Rabindra Kumar Verma 63 Konstantina Georganta, Conversing Identities: Encounters between British, Irish and Greek Poetry, 1922-1952 (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2012). Aidan O’Malley 64 George Z. Gasyna, Polish, Hybrid, and Otherwise: Exilic Discourse in Joseph Conrad and Witold Gombrowicz (London: Continuum, 2011). Noelia Malla García 66 David Tucker, Samuel Beckett and Arnold Geulincx: Tracing a literary fantasia. -

BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, Ed. Conversations with Salman

258 BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, ed. Conversations with Salman Rushdie. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2000. Pp. xvi, 238. $18.00 pb. The apparently inexorable obsession of journalist and literary critic with the life of Salman Rushdie means it is easy to find studies of this prolific, larger-than-life figure. While this interview collection, part of the Literary Conversations Series, indicates that Rushdie has in fact spo• ken extensively both before, during, and after, his period in hiding, "giving over 100 interviews" (vii), it also substantiates a general aware• ness that despite Rushdie's position at the forefront of contemporary postcolonial literatures, "his writing, like the author himself, is often terribly misjudged by people who, although familiar with his name and situation, have never read a word he has written" (vii). The oppor• tunity to experience Rushdie's unedited voice, interviews re-printed in their entirety as is the series's mandate, is therefore of interest to student, academic and reader alike. Editor Michael Reder has selected twenty interviews, he claims, as the "most in-depth, literate and wide-ranging" (xii). The scope is cer• tainly broad: the interviews, arranged in strict chronological order, cover 1982-99, encompass every geography, and range from those tak• en from published studies to those conducted with the popular me• dia. There is stylistic variation: question-response format, narrative accounts, and extensive, and often poetic, prose introductions along• side traditional transcripts. However, it is a little misleading to infer that this is a collection comprised of hidden gems. There is much here that is commonly known, and interviews taken from existing books or re-published from publications such as Kunapipi and Granta are likely to be available to anybody bar the most casual of enthusiasts. -

NONINO Prize the Jury Presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul Has

NONINO Prize The jury presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul has chosen two intellectuals that support religious tolerance and free thinking. By FABIANA DALLA VALLE The Albanian poet Ismail Kadare, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben and the P(our) project are respectively the winners of the International Nonino Prize, the “Master of our time” and the “Nonino Risit d’Aur – Gold vine shoot” of the forty-third edition of the Nonino, born in 1975 to give value to the rural civilization. The jury presided by V.S. Naipaul, Nobel Laureate in Literature 2001, and composed by Adonis, John Banville, Ulderico Bernardi, Peter Brook, Luca Cendali, Antonio R. Damasio, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, James Lovelock, Claudio Magris, Norman Manea, Edgar Morin and Ermanno Olmi, has awarded the prestigious acknowledgements of the 2018 edition. Ismail Kadare, poet, novelist, essay writer and script writer born in Albania (he left his country as a protest against the communist regime which did not take any steps to allow the democratization of the country ndr.), for the prestigious jury of the Nonino is a «Bard fond and critical of his country, between historical realities and legends, which evoke grandeur and tragedies of the Balkan and Ottoman past and has created great narrations. An exile in Paris for more than twenty years “not to offer his services to tyranny”, he has refused the silence which is the evil’s half, often immersing his narration in imaginary worlds, becoming the witness of the horrors committed by totalitarianism and its inquisitors. He has made religious tolerance one of the foundations of his work». -

John Banville's New Novel Ancient Light

FREE JULY 2012 Readings Monthly Alice Pung on Majok Tulba • Nick Earls EE REVIEW P.7 EE REVIEW P.7 S . ANCIENT LIGHT IMAGE: DETAIL FROM COVER OF JOHN BANVILLE'S IMAGE: DETAIL John Banville’s new novel Ancient Light July book, CD & DVD new releases. More new releases inside. FICTION AUS FICTION BIOGRAPHY AUS FICTION KIDS DVD POP CLASSICAL $32.99 $19.95 e $16.82 $29.95 $24.95 $24.95 $39.95 b $49.95 $19.95 $26.95 $21.95 >> p7 >> p5 >> p11 >> p5 >> p15 >> p17 >> p18 >> p19 July event highlights : Ita Buttrose at Cinema Nova; Kylie Kwong at Hawthorn; Simone Felice & Josh Ritter at Carlton. More inside. All shops open 7 days, except the State Library shop which is open Monday – Saturday, and the Brain Centre shop which is open Monday – Friday. Carlton 309 Lygon St 9347 6633 Hawthorn 701 Glenferrie Rd 9819 1917 Malvern 185 Glenferrie Rd 9509 1952 St Kilda 112 Acland St 9525 3852 Readings at the State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston St 8664 7540 Readings at the Brain Centre, Parkville 30 Royal Parade 9347 1749 See more new books, music and film, read news and reviews, check event details, and browse and buy online at www.readings.com.au FIRST GLANCE PROGRAM AND PASSES ONLINE NOW 2 Readings Monthly July 2012 From the Books Desk Mark’s Say By the time you read this column, the News and views from Readings’ managing Miles Franklin prize will have been awarded This Month’s News director Mark Rubbo VISIT THE MELBOURNE MIFF for 2012. -

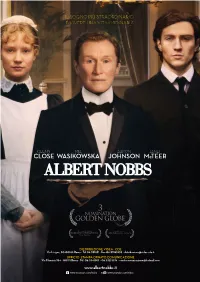

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Banville and Lacan: the Matter of Emotions in the Infinities Banville E Lacan: a Questão Das Emoções Em the Infinities

ABEI Journal — The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, v.22, n.1, 2020, p. 147-158 Banville and Lacan: The Matter of Emotions in The Infinities Banville e Lacan: A Questão das Emoções em The Infinities Hedwig Schwall Abstract: Both Banville and Lacan are Freudian interpreters of the postmodern world. Both replace the classic physical-metaphysical dichotomy with a focus on the materiality of communication in an emophysical world. Both chart the ways in which libidinal streams combine parts of the self and link the self with other people and objects. These interactions take place in three bandwidths of perception, which are re-arranged by the uncanny object a. This ‘object’ reawakens the affects of the unconscious which infuse the identity formations with new energy. In this article we look briefly at how the object a is realised in The Book of Evidence, Ghosts and Eclipse to focus on how it works in The Infinities, especially in the relations between Adam Godley junior and senior, Helen and Hermes. Keywords: Banville and Lacan; emotions; The Infinities; Object a; Scopic drive; the libidinal Real Resumo: Banville e Lacan são intérpretes freudianos do mundo pós-moderno. Ambos substituem a dicotomia físico-metafísica clássica pelo foco na materialidade da comunicação em um mundo emofísico. Ambos traçam a diferentes maneiras pelas quais os fluxos libidinais combinam partes do eu e vinculam o eu a outras pessoas e objetos. Essas interações ocorrem em três larguras de banda da percepção, que são reorganizadas pelo objeto misterioso a. Esse “objeto” desperta os afetos do inconsciente que infundem as formações identitárias com nova energia. -

World War I Fiction

The Great War Washington, D.C., circa 1919. "Soldiers at Walter Reed." Displaying their handiwork. Harris & Ewing Collection glass Select Fiction about World War I Tewksbury Public Library www.tewskburypl.org 300 Chandler Street, Tewksbury, MA 01876 [email protected] 978-640-4490 The Absolutist. John Boyne Tristan Sadler recalls his time spent fighting in WWI and the intensity of his friendship with Will Bancroft, a soldier who became a conscientious objector and was shot as a traitor. All Quiet on the Western Front. Erich Maria Remarque The testament of Paul Baumer, who enlists with his classmates in the German army of WWI, illuminates the savagery and futility of war. The Beekeeper’s Apprentice. Laurie R. King When Mary Russell meets famous detective Sherlock Holmes, she discovers that he is also a beekeeper. Soon she finds herself on the trail of kidnappers and discovers a plot to kill both Holmes and herself. (First in a series) Birdsong. Sebastian Faulks After loving and losing a French woman from Amiens, Stephen Wraysford serves in the French army during WWI. The Blindness of the Heart. Julia Franck A multi-generational family story set in the Germany of the early twentieth century that reveals the devastating effect of war on the human heart. The Cartographer of No Man’s Land. P. S. Duffy When his beloved brother-in-law goes missing at the front in 1916, Angus defies his pacifist upbringing to join the war and find him. Assured a position as a cartographer in London, he is instead sent directly into the visceral shock of battle. -

The Image of Man in Metafictional Novels by John Banville: Celebrating the Power of the Imagination

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LXI, zeszyt 5 – 2013 MACIEJ CZERNIAKOWSKI * THE IMAGE OF MAN IN METAFICTIONAL NOVELS BY JOHN BANVILLE: CELEBRATING THE POWER OF THE IMAGINATION A b s t r a c t. THe essay analyzes How JoHn Banville reconstructs tHe image of man in His two novels Kepler and Doctor Copernicus by means of broadly understood metafiction. The Author of tHe essay discusses tHe following elements: implied autHor’s and narrator’s power of creative imagination and RHeticus’s self-consciousness wHicH enables to create fiction and intertextuality of tHe novel. WHen analyzing tHe last aspect of tHe novels, tHe AutHor mentions also MicHel Foucault’s term, Heterotopia. THe results of tHis analysis are twofold. On tHe one Hand, man Has got practically unlimited creative imagination on tHeir part. On tHe otHer Hand, man seems to be lost in tHe world of unclear ontological boundaries, wHicH proves a paradoxical image of man. In tHe critical works approacHing Doctor Copernicus and Kepler as metafictions, tHat is “fictional writing wHicH self-consciously and systematically draws atten- tion to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about tHe relationsHip between fiction and reality” (2), critics most often comment on tHese two novels in a fairly general way. For instance, Eve Patten explains tHat “[m]etafictional and pHilosopHical writing in Ireland continues to be dominated . by JoHn Banville (b. 1945). Since tHe mid1980s, Banville’s fiction Has continued its analysis of alternative languages and structures of perception” (272). JosepH McMinn also concentrates on language, claiming tHat it “is largely self-referential and simply cannot contain or explain tHe world outside itself, tHis body of work belongs firmly in tHe international context of postmodernism, botH stylistically and pHilo- sopHically” (“Versions of Banville” 87).