The Broken Jug (1994), John Banville S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Im Kampf, Penthesilea Und Achill”. Pentesilea Y Aquiles: ¿Kleist Y Goethe?

“Im Kampf, Penthesilea und Achill”. Pentesilea y Aquiles: ¿Kleist y Goethe? Raúl TORRES MARTÍNEZ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Este pequeño ensayo pretende revisar la vieja teoría del agón literario entre Heinrich von Kleist y Johann Wolfgang Goethe, aportando algo novedoso desde el punto de vista de la Grecística, y tomando, a modo de ilustración, elementos de la tragedia Pentesilea del escritor prusiano. La Antigüedad, la androginia y el agón mismo son puntos de partida desde los que podemos sacar provecho al aproximarnos al llamado Goethezeit. PALABRAS CLAVE: mitología griega, homoerotismo, Kleist, Pentesilea, Goethezeit, Goethe. This little essay aims at elaborating on the old theory of the literary agon between the german poets Heinrich von Kleist and Johann. Wolfgang Goethe. It provides some Greek elements until almost unnoticed to modern scholars, taking, as a sort of example, the tragedy Penthesilea of the prusian author. Greek antiquity, an- drogyny and the agon itself, are points of view from wich we may win new perspectives in approaching the so-called Goethezeit. KEYWORDS: Greek mythology, homoerotism, Kleist, Penthesilea, Goethezeit, Goethe. I Wilhelm von Humboldt, en un locus classicus (Humboldt, 2002: 609) hoy, sin embar- go, casi desconocido, “Acerca de la diferencia entre los sexos y su influjo sobre la naturaleza orgánica”, publicado en 1795 en Die Horen, la revista de Schiller, dice a la letra: “La naturaleza no sería naturaleza sin él [sc. el concepto de sexo], su meca- nismo se detendría y, tanto la atracción (“Zug”) que une a todos los seres, como la lucha que todos necesitan para armarse con la energía que a cada uno le es propia, desaparecerían, si en lugar de la diferencia de sexos tuviéramos una igualdad aburrida y floja” (Humboldt, 2002: 268). -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Myspace.Com - - 43 - Male - PHILAD

MySpace.com - WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM - 43 - Male - PHILAD... http://www.myspace.com/recordcastle Sponsored Links Gear Ink JazznBlues Tees Largest selection of jazz and blues t-shirts available. Over 100 styles www.gearink.com WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM is in your extended "it's an abomination that we are in an network. obama nation ... ron view more paul 2012 ... balance the budget and bring back tube WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Latest Blog Entry [ Subscribe to this Blog ] amps" [View All Blog Entries ] Male 43 years old PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Blurbs United States About me: I have been an avid music collector since I was a kid. I ran a store for 20 years and now trade online. Last Login: 4/24/2009 I BUY PHONOGRAPH RECORDS ( 33 lp albums / 45 rpms / 78s ), COMPACT DISCS, DVD'S, CONCERT MEMORABILIA, VINTAGE POSTERS, BEATLES ITEMS, KISS ITEMS & More Mood: electric View My: Pics | Videos | Playlists Especially seeking Private Pressings / Psychedelic / Rockabilly / Be Bop & Avant Garde Jazz / Punk / Obscure '60s Funk & Soul Records / Original Contacting WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM concert posters 1950's & 1960's era / Original Beatles memorabilia I Offer A Professional Buying Service Of Music Items * LPs 45s 78s CDS DVDS Posters Beatles Etc.. Private Collections ** Industry Contacts ** Estates Large Collections / Warehouse finds ***** PAYMENT IN CASH ***** Over 20 Years experience buying collections MySpace URL: www.myspace.com/recordcastle I pay more for High Quality Collections In Excellent condition Let's Discuss What You May Have For Sale Call Or Email - 717 209 0797 Will Pick Up in Bucks County / Delaware County / Montgomery County / Philadelphia / South Jersey / Lancaster County / Berks County I travel the country for huge collections Print This Page - When You Are Ready To Sell Let Me Make An Offer ----------------------------------------------------------- Who I'd like to meet: WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Friend Space (Top 4) WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM has 57 friends. -

Die Hermannsschlacht

WWWW ^W^H^I INTRODUCTION AND NOTES TO KLEIST'S DIE HERMANNSSCHLACHT BY FRANCES EMELINE GILKERSON, A. B. '03. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1904 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Q^/iß^Mt St^uljIcI^ bZL^/teAsC^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF 4 PREFACE. This volume has been prepared to meet the demand for an .edition of Kleist' s "Die Hermannsschlacht" with English Introduction and Notes. It is designed for advanced classes, capable of reading and understanding the play as literature. As a fairly good reading knowledge of the language is taken forgranted, few grammatical passages are explained. The Introduction is intended to give such historical, biographi- cal and critical material as will prepare the student for the most profitable and appreciative reading of the play. It has been said that Kleist is one of those poets whose work cannot be fully under- stood without a knowledge of their lives. But this is perhaps less true of "Die Hermannsschlacht" than of some of Kleist' s other works. For an intelligent understanding of this drama an intimate knowledge of the condition of Germany in the early part of the Nineteenth Century is even more essential than a knowledge of the poet's life. The Notes contain such suggestions regarding classical, geo- graphical, and vague allusions as are deemed necessary or advisable for understanding this great historical drama. -

The Broken Jug As an Experiment with Thomas Hobbes' Political Theory

The Delta Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 9 Spring 2008 The Broken Jug as an Experiment with Thomas Hobbes' Political Theory Mark Kasperczyk '10 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/delta Recommended Citation Kasperczyk '10, Mark (2008) "The Broken Jug as an Experiment with Thomas Hobbes' Political Theory," The Delta: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/delta/vol3/iss1/9 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Kasperczyk '10: <em>The Broken Jug</em> as an Experiment with Thomas Hobbes' Poli The Broken Jug as an Experiment with Thomas Hobbes' (143). Thus, one person is made a sovereign Political Theory agreement between all others to offer part oU (namely, the right to self-government) so that Mark Kasperczyk peacefully, without quarrel. What makes a discussion of Hobbes ir Illinois Wesleyan University recently put on a production Broken Jug most interesting is his views on tr of The Broken Jug by John Banville. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

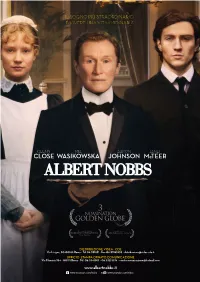

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-Like Authors in Irish Fiction: the Case of John Banville

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-like Authors in Irish Fiction: The Case of John Banville Roberta Gefter Wondrich University of Trieste Abstract This article aims at exploring the crucial correlation between love (erosldesire) and writing, death and writing and God-like authorial strategies as a relevant feature of postmodernist fiction mainly as it unfolds in the work of Ireland's most important (postmodernist) novelist, John Banville. This issue is highly relevant in the context of postmodernism as, according to Brian McHale, postmodern fiction has thoroughly exploited both love and death not only as topics but essentially as formally relevant features of the novel, by systematically foregrounding the relation existing between author, characters and reader, al1 entangled in a web of love, seduction and deferred annihilation, and by transgressing the related ontological boundaries. In this regard, then, Banville's novels (notably the 'tetralogy of art', narnely The Book ofEvidence (1989), Ghosts (1993), Athena (1995) and The Untouchable (1998)) thoroughly explore and foregromd-probably for the first time in Irish writing-both the notion of love and desire as a creative activity, of textual narrative as necessarily seductive and, finally, the time-hoiioured equation of life with discourse/narration, thus recalling the problematic motif of the impossibility and necessity of discourse. In the context of Irish fiction, postmodernist literary strategies have not been practised too extensively in the last decades, while it is by now widely acknowledged that a great many of the main features of postmodernist writing had already been inaugurated by the titans of the protean Irish 'modernism': 1 am obviously thinking of Joyce-especially in Finnegan S Wake-and Flann O'Brien. -

Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist

Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist 098195572X, 9780981955728, Heinrich von Kleist, Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist, 2010, 283 pages, Archipelago Books, 2010, In this extraordinary and unpredictable cross-section of the work of one of the most influential free spirits of German letters, Peter Wortsman captures the breathlessness and power of Heinrich von Kleist’s transcendent prose. These tales, essays, and fragments move across inner landscapes, exploring the shaky bridges between reason and feeling and the frontiers between the human psyche and the divine. From the "The Earthquake in Chile," his damning invective against moral tyranny; to "Michael Kohlhaas," an exploration of the extreme price of justice; to "The Marquise of O . ," his twist on the mythic triumph of love story; to his essay "On the Gradual Formulation of Thoughts While Speaking," which tracks the movements of the unconscious decades before Freud; Kleist unrelentingly confronts the dangers of self-deception and the ultimate impossibility of existence ina world of absolutes. Wortsman’s illuminating afterword demystifies Kleist’s vexed history, explaining how the century after his death saw Kleist’s legacy transformed from that of a largely derided playwright into a literary giant who would inspire Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka. The concerns of Heinrich von Kleist are timeless. The mysteries in his fiction and visionary essays still breathe. file download musu.pdf 341 pages, Heinrich von Kleist, 1982, ISBN:0826402631, Plays Selected Prose of Heinrich Von Kleist