John Banville's Scientific Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

Listed by Author ST

Book List Listed by Author ST. ANDREW'S CHURCH LIBRARY INVENTORY Page 1 of 69 January 2017 DEWEY AUTHOR TITLE CAT YA H Fic Aarsen, Carolyne Heartsong Presents - A Family-Style Christmas Book 220.7 Aaseng, Rolf E. Sacred Sixty-Six, The Book YA Fic Ackerman, Karen Leaves in October, The Book E Adams, George Good Shepherd Storybook, The Book 248 Adams, Lane How Come It's Taking Me So Long to Get Better ? Book 242 Adams, Nate Energizers, Light Devotions to Keep Your Faith Growing Book R 227.91 Adamson, James New International Commentary - The Epistle of James, The Book MI African Children's Choir Arms Around the World CD (Music) 921 Aikman, David Man of Faith, The Spiritual Journey of George W. Bush, A Book 242 Akempis, Thomas Imitation of Christ Book G 248.3 Al-Anon As We Understand Book 921 Albom, Mitch Have a little faith Book 920 Albrecht, Donna C. Favorite Bible Stories of famous people; I love to tell the storyBook 290 Albrecht, Mark Reincarnation, A Christian Appraisal Book 266 Alcoholics Anonymous Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions Book 236.2 Alcorn, Randy In Light of Eternity Book Fic Alcorn, Randy Lord Foulgrin's Letters Book Fic Alcorn, Randy Safely Home Book Fic Alcott, Louisa May Inheritance, The Book 243 Aldrich, Joseph C. Gentle Persuasion Book YA H Fic Alexander, Hannah Heartsong Presents - The Healing Promise Book YA H Fic Alexander, Kathryn Heartsong Presents - Twin Wishes Book 222.1 Alexander, T. Desmond and Baker, DavidDictionary W. of the Old Testament: Pentateuch Book Fic Alexander, Tamera Rekindled Book Fic Alexander, Tamera Remembered Book Fic Alexander, Tamera Revealed Book 222.9 Allegro, John Dead Sea Scrolls, A Reappraisal, The Book 248.86 Allen, Charles L. -

BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, Ed. Conversations with Salman

258 BOOK REVIEWS Michael R. Reder, ed. Conversations with Salman Rushdie. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2000. Pp. xvi, 238. $18.00 pb. The apparently inexorable obsession of journalist and literary critic with the life of Salman Rushdie means it is easy to find studies of this prolific, larger-than-life figure. While this interview collection, part of the Literary Conversations Series, indicates that Rushdie has in fact spo• ken extensively both before, during, and after, his period in hiding, "giving over 100 interviews" (vii), it also substantiates a general aware• ness that despite Rushdie's position at the forefront of contemporary postcolonial literatures, "his writing, like the author himself, is often terribly misjudged by people who, although familiar with his name and situation, have never read a word he has written" (vii). The oppor• tunity to experience Rushdie's unedited voice, interviews re-printed in their entirety as is the series's mandate, is therefore of interest to student, academic and reader alike. Editor Michael Reder has selected twenty interviews, he claims, as the "most in-depth, literate and wide-ranging" (xii). The scope is cer• tainly broad: the interviews, arranged in strict chronological order, cover 1982-99, encompass every geography, and range from those tak• en from published studies to those conducted with the popular me• dia. There is stylistic variation: question-response format, narrative accounts, and extensive, and often poetic, prose introductions along• side traditional transcripts. However, it is a little misleading to infer that this is a collection comprised of hidden gems. There is much here that is commonly known, and interviews taken from existing books or re-published from publications such as Kunapipi and Granta are likely to be available to anybody bar the most casual of enthusiasts. -

Historicist Inquiry in the New Historicism and British Historiographic Metafiction

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi Cilt: 15 / Sayı: I/ss. 39-52 Historicist Inquiry in The New Historicism and British Historiographic Metafiction Doç. Dr. Serpil OPPERMANN* ÖZET Bu makale "Yeni Tarihselcilik" kuramının tarihi metinlere, söylemine ve tarih kavramına getirdiği sorgulama ve eleştirel bakışın son dönem İngiliz romanında nasıl kurgusal düzlemde incelendiğini tartışmaktadır . "Yeni Tarihselcilik" kuramının edebiy- at eleştirisinde ve tarih araştırmalarında tartışmaya açtığı önemli fikirlerin ve eleştirel yöntemlerin, tarihi olayları ve kişileri postmodern bir yapı içinde kurgusallaştıran İngiliz romanında kullanımı, ve kurgusal gerçek! tarihi gerçeklik arasındaki ikilemin ortadan kalkması bu makalenin ana temasını oluşturmaktadır. Roman ve kuram arasındaki paralellik ve tarih metinleriyle edebiyat metinlerinin yazılımındaki ortak özellikler örneklerle incelenmekte, ve sonuç olarak tarih yazılımı ve roman sanatı arasındaki benzerliklere dikkat çekilmektedir. One of the resurgent new trends in British metafiction is the revival of interest in his- tory. Significantly history means both "historiography" - a particulardiscursive disei- pline- and "history"- the actual events this diseipline investigates. Since history signi- fies both a form of discourse about facts and fac1s themselves, it has been the major focus of attention in contemporary critical theory over the past decade in Britain and the U.S. Now at the end of the 1990s this interest in history has become the central critical concem of the contemporary novelists in Britain. British fiction today has discovered an important means of articulating not only its rich cultural heritage but also the ongoing contemporary debate on historical studies. The kind of novel this artide will focus on is well- known as historiographic metafiction. The historiographers' interrogation of the discourses of history, and their inquiry into the nature of the "truth of history," have gone into the fictional fabrics of British historiographic metafiction. -

NONINO Prize the Jury Presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul Has

NONINO Prize The jury presided by the Nobel Laureate Naipaul has chosen two intellectuals that support religious tolerance and free thinking. By FABIANA DALLA VALLE The Albanian poet Ismail Kadare, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben and the P(our) project are respectively the winners of the International Nonino Prize, the “Master of our time” and the “Nonino Risit d’Aur – Gold vine shoot” of the forty-third edition of the Nonino, born in 1975 to give value to the rural civilization. The jury presided by V.S. Naipaul, Nobel Laureate in Literature 2001, and composed by Adonis, John Banville, Ulderico Bernardi, Peter Brook, Luca Cendali, Antonio R. Damasio, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, James Lovelock, Claudio Magris, Norman Manea, Edgar Morin and Ermanno Olmi, has awarded the prestigious acknowledgements of the 2018 edition. Ismail Kadare, poet, novelist, essay writer and script writer born in Albania (he left his country as a protest against the communist regime which did not take any steps to allow the democratization of the country ndr.), for the prestigious jury of the Nonino is a «Bard fond and critical of his country, between historical realities and legends, which evoke grandeur and tragedies of the Balkan and Ottoman past and has created great narrations. An exile in Paris for more than twenty years “not to offer his services to tyranny”, he has refused the silence which is the evil’s half, often immersing his narration in imaginary worlds, becoming the witness of the horrors committed by totalitarianism and its inquisitors. He has made religious tolerance one of the foundations of his work». -

Albert Nobbs Notes FINAL 10.8.11 ITA

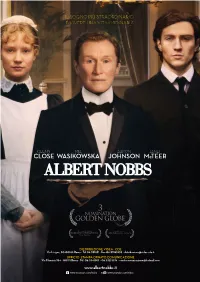

3 NOMINATION GOLDEN GLOBE ® DISTRIBUZIONE VIDEA 5 CDE Via Livigno, 50-00188 Roma - Tel 06.331851 - Fax 06.33185255 - [email protected] UFFICIO STAMPA ORNATO COMUNICAZIONE Via Flaminia 954 - 00191 Roma - Tel. 06.3341017 - 06.33213374 - [email protected] www.albertnobbs.it www.facebook.com/videa www.youtube.com/videa Sinossi La pluripremiata attrice Glenn Close (Albert Nobbs) indossa i panni di una donna coinvolta in un insolito triangolo amoroso. Travestita da uomo per poter lavorare e sopravvivere nell’Irlanda del XIX secolo, più di trent’anni dopo si ritrova prigioniera della sua stessa finzione. Nel prestigioso cast internazionale, Mia Wasikowska (Helen), Aaron Johnson (Joe) e Brendan Gleeson (Dr. Holloran), oltre a Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Janet McTeer, Brenda Fricker e Pauline Collins. Rodrigo Garcia dirige il film basato su un racconto dell’autore irlandese George Moore, adattato da Glenn Close insieme a John Banville, vincitore del premio Man Booker, e a Gabriella Prekop. NOTE DI PRODUZIONE IL LEGAME DI GLENN CLOSE con il personaggio di Albert Nobbs risale a Quasi 30 anni fa, ai tempi in cui recitò – nel 1982 – nella rappresentazione teatrale di Simone Benmussa, ispirata al racconto breve Albert Nobbs, scritto dall’autore irlandese del XIX secolo, George Moore. “Credo che Albert sia un grande personaggio e la storia, in tutta la sua disarmante semplicità, è molto potente dal punto di vista emotivo”, dichiara Close, la cui apparizione in Quella produzione Off-Broadway le valse critiche eccellenti e un Obie Award. Nonostante i grandi successi che Close ha collezionato nel corso della sua brillante carriera, quel personaggio le è rimasto dentro. -

Albert Nobbs

Albert Nobbs Albert Nobbs, ALBERT NOBBS, RODRIGO GARCIA, Golden Globe Award, role, characters, film credits, John Banville, John Boorman, Julie Lynn, starring role, television, Simone Benmussa, Brendan Gleeson, Radha Mitchell, Harry Potter, Aaron Johnson, Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Award, George Roy Hill, Kerry Washington, Margarethe Cammermeyer, Mia Wasikowska, Joe Layton, Directors' Fortnight, Neil Jordan, BBC comedy series, Florida Film Festival, European Film Academy, award nomination, Arlene Kelly, Sweet Emma Dear Bobe, Dublin Theatre Festival, television drama, Michael Cristofer, Franco Zeffirelli, Harvey Goldsmith, Winner Locarno Film Festival, Harold Prince, Irish actor, Fountain House, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Richard Pearce, Norma Desmond, Merchant Ivory, Stephen Frears, Jack Hofsiss, Stephen Herek, Royal National Theatre, Tony Awards, Richard Marquand, Fatal Attraction, Feature Film Commission, Christopher Walken, Barbet Schroeder, Joe, MAIN characters, National Association of Theatre Owners, Andrei Konchalovsky, International Mental Health Research Organization, Monica Rawling, Glenn Jordan, Rose Troche, Panthera Conservation Advisory Committee, Julian Morris, Danny Boyle, JOE Aaron Johnson, British independent film, Kristen Scott Thomas, Golden Globe nomination, Simon Wincer, Colin Farrell, RODRIGO GARCIA GABRIELLA PREKOP JOHN BANVILLE GLENN CLOSE, GLENN CLOSE, Bonnie Curtis, John Travolta, Golden Globe, Michael Vartan, John Lennon, Rhys Meyers, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, London Film Critics, -

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-Like Authors in Irish Fiction: the Case of John Banville

Postmodern Love, Postmodern Death and God-like Authors in Irish Fiction: The Case of John Banville Roberta Gefter Wondrich University of Trieste Abstract This article aims at exploring the crucial correlation between love (erosldesire) and writing, death and writing and God-like authorial strategies as a relevant feature of postmodernist fiction mainly as it unfolds in the work of Ireland's most important (postmodernist) novelist, John Banville. This issue is highly relevant in the context of postmodernism as, according to Brian McHale, postmodern fiction has thoroughly exploited both love and death not only as topics but essentially as formally relevant features of the novel, by systematically foregrounding the relation existing between author, characters and reader, al1 entangled in a web of love, seduction and deferred annihilation, and by transgressing the related ontological boundaries. In this regard, then, Banville's novels (notably the 'tetralogy of art', narnely The Book ofEvidence (1989), Ghosts (1993), Athena (1995) and The Untouchable (1998)) thoroughly explore and foregromd-probably for the first time in Irish writing-both the notion of love and desire as a creative activity, of textual narrative as necessarily seductive and, finally, the time-hoiioured equation of life with discourse/narration, thus recalling the problematic motif of the impossibility and necessity of discourse. In the context of Irish fiction, postmodernist literary strategies have not been practised too extensively in the last decades, while it is by now widely acknowledged that a great many of the main features of postmodernist writing had already been inaugurated by the titans of the protean Irish 'modernism': 1 am obviously thinking of Joyce-especially in Finnegan S Wake-and Flann O'Brien. -

The Image of Man in Metafictional Novels by John Banville: Celebrating the Power of the Imagination

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LXI, zeszyt 5 – 2013 MACIEJ CZERNIAKOWSKI * THE IMAGE OF MAN IN METAFICTIONAL NOVELS BY JOHN BANVILLE: CELEBRATING THE POWER OF THE IMAGINATION A b s t r a c t. THe essay analyzes How JoHn Banville reconstructs tHe image of man in His two novels Kepler and Doctor Copernicus by means of broadly understood metafiction. The Author of tHe essay discusses tHe following elements: implied autHor’s and narrator’s power of creative imagination and RHeticus’s self-consciousness wHicH enables to create fiction and intertextuality of tHe novel. WHen analyzing tHe last aspect of tHe novels, tHe AutHor mentions also MicHel Foucault’s term, Heterotopia. THe results of tHis analysis are twofold. On tHe one Hand, man Has got practically unlimited creative imagination on tHeir part. On tHe otHer Hand, man seems to be lost in tHe world of unclear ontological boundaries, wHicH proves a paradoxical image of man. In tHe critical works approacHing Doctor Copernicus and Kepler as metafictions, tHat is “fictional writing wHicH self-consciously and systematically draws atten- tion to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about tHe relationsHip between fiction and reality” (2), critics most often comment on tHese two novels in a fairly general way. For instance, Eve Patten explains tHat “[m]etafictional and pHilosopHical writing in Ireland continues to be dominated . by JoHn Banville (b. 1945). Since tHe mid1980s, Banville’s fiction Has continued its analysis of alternative languages and structures of perception” (272). JosepH McMinn also concentrates on language, claiming tHat it “is largely self-referential and simply cannot contain or explain tHe world outside itself, tHis body of work belongs firmly in tHe international context of postmodernism, botH stylistically and pHilo- sopHically” (“Versions of Banville” 87). -

On Not Yet Being Christian: J.M. Coetzee's Slow Man and the Ethics of Being (Un)Interesting

Postcolonial Text, Vol 9, No 1 (2014) On Not Yet Being Christian: J.M. Coetzee’s Slow Man and the Ethics of Being (Un)Interesting Craig Smith Independent Scholar Slow Man, J.M. Coetzee’s first Australian novel, has been widely perceived as somewhat of a non-event in an otherwise celebrated literary career. As Roman Silvani explains, the novel “got mixed reviews”1 upon its initial publication and subsequently “has not provoked a great number of literary critics to analyze it” (135), making it a marginal text in the Coetzeean canon. The relatively few extant commentaries on Slow Man are in broad agreement on two issues: on the one hand, it appears radically disconnected from the fiction Coetzee wrote before emigrating to Australia,2 and, on the other, it is anything but a fast-paced, stimulating novel. One might be tempted to suspect that there is a connection to be made here, and, indeed, critical opinion tends toward this conclusion. If, as Tim Mehigan contends, “Coetzee’s thematic concerns in the first novel published after his relocation to Australia bear no South African imprint, nor even a faint afterimage of South Africa” (“Slow Man” 192), the apparent correlative of this emerges in critical assessments of the novel that deem it to be “a slow book” (Silvani 135) that is less “successful” when contrasted with Coetzee’s other novels (Hayes 225). If the book’s initial minimal “momentum…is lost” (Hope) with the appearance in the novel of Coetzee’s familiar Australian authorial alter-ego, the “tiresome” and “tedious” (Banville) Elizabeth Costello, that loss of momentum has much to do with Slow Man’s apparent inability to engage with its readers’ emotional and critical sensibilities following its author’s relocation to an Australian setting that, in Slow Man at least, does not bring with it the contextual relevancy attendant to his South African fiction. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997).