Does Literary Translingualism Matter? Reflections on the Translingual and Isolingual Text Steven G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature By Derek M. Ettensohn M.A., Brown University, 2012 B.A., Haverford College, 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Derek M. Ettensohn This dissertation by Derek M. Ettensohn is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ___________________ _________________________ Olakunle George, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ___________________ _________________________ Timothy Bewes, Reader Date ___________________ _________________________ Ravit Reichman, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ___________________ __________________________________ Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of “Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature” by Derek M. Ettensohn, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2014. This project evaluates the twinned discourses of globalism and humanitarianism through an analysis of the body in the postcolonial novel. In offering celebratory accounts of the promises of globalization, recent movements in critical theory have privileged the cosmopolitan, transnational, and global over the postcolonial. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of globalism, these theorists have often turned to transnational fiction as supplying a corrective dose of humanitarian sentiment that guards a global affective community against the potential exploitations and excesses of neoliberalism. While authors such as Amitav Ghosh, Nuruddin Farah, and Rohinton Mistry have been read in a transnational, cosmopolitan framework––which they have often courted and constructed––I argue that their theorizations of the body contain a critical, postcolonial rejoinder to the liberal humanist tradition that they seek to critique from within. -

Professor F. Nick Nesbitt Professor, Dept. of French & Italian 312 East

Professor F. Nick Nesbitt Professor, Dept. of French & Italian 312 East Pyne Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] tel. 609-258-7186 [email protected] https://princeton.academia.edu/NickNesbitt Senior Researcher, Dept. of Modern Philosophy Czech Academy of Sciences (2019-21) http://mcf.flu.cas.cz/en Education Harvard University Ph.D., Romance Languages and Literatures, November 1997 Specialization in Francophone Literature, Minor: Lusophone Language and Literature M.A., Romance Languages and Literatures, May 1990 Colorado College B.A. (cum laude) French Literature, 1987 Berklee College of Music Performance Studies (Jazz Guitar) 1990-1995 Hamilton College Junior Year in France Studies at Université de Paris IV (Sorbonne), L’Institut Catholique, 1985-1986 Publications Books: 1. Caribbean Critique: Antillean Critical Theory from Toussaint to Glissant Liverpool University Press, 2013. Reviews: -‘This is a very important and exciting book. Extending to the whole of the French Caribbean his previous work on the philosophical bases of the Haitian Revolution, Nesbitt has produced the first-ever account of the region’s writing from a consistently philosophical, as distinct from literary or historical, standpoint.’ Professor Celia Britton, University College London. -‘While Nesbitt’s work deals primarily with Caribbean and European political philosophy, his interrogations apply to more far-reaching questions involving the contemporary world order. […] The interrogations that Nesbitt’s work leads us through […] are of utmost currency in our work as scholars of the contemporary world.’ Alessandra Benedicty (CUNY), Contemporary French Civilization 39.3 (2014) -‘The book fills an important gap in francophone Caribbean studies, which […] has not previously been subject to such a rigorously philosophical critical treatment. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

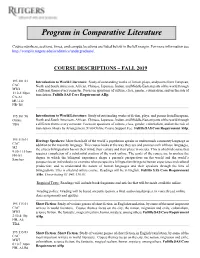

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

VON DER MUTTERSPRACHE ZUR SPRACHMUTTER: YOKO TAWADA’S CREATIVE MULTILINGUALISM AN EXHIBITION ON THE OCCASION OF YOKO TAWADA’S VISIT TO OXFORD AS DAAD WRITER IN RESIDENCE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, TAYLORIAN (VOLTAIRE ROOM) HILARY TERM 2017 ExhiBition Catalogue written By Sheela Mahadevan Edited By Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann and Chantal Wright Contributed to by Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann, Chantal Wright, Emma HuBer and ChriStoph Held Photo of Yoko Tawada Photographer: Takeshi Furuya Source: Yoko Tawada 1 Yoko Tawada’s Biography: CABINET 1 Yoko Tawada was born in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan. She began to write as a child, and at the age of twelve, she even bound her texts together in the form of a first book. She learnt German and English at secondary school, and subsequently studied Russian literature at Waseda University in 1982. After this, she intended to go to Russia or Poland to study, since she was interested in European literature, especially Russian literature. However, her university grant to study in Poland was withdrawn in 1980 because of political unrest, and instead, she had the opportunity to work in Hamburg at a book trade company. She came to Europe by ship, then by trans-Siberian rail through the Soviet Union, Poland and the DDR, arriving in Berlin. In 1982, she studied German literature at Hamburg University, and thereafter completed her doctoral work on literature at Zurich University. Among various authors, she studied the poetry of Paul Celan, which she had already read in Japanese. Indeed, she comments on his poetry in an essay entitled ‘Paul Celan liest Japanisch’ in her collection of essays named Talisman and also in her essay entitled ‘Die Niemandsrose’ in the collection Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte. -

Haiti Unbound a Spiralist Challenge to the Postcolonial Canon H

HAITI UNBOUND A SPIRALIST CHALLENGE TO THE POSTCOLONIAL CANON H Both politically and in the fields of art and literature, Haiti has long been relegated to the margins of the so-called ‘New World’. Marked by exceptionalism, the voices of some of its AITI most important writers have consequently been muted by the geopolitical realities of the nation’s fraught history. In Haiti Unbound, Kaiama L. Glover offers a close look at the works of three such writers: the Haitian Spiralists Frankétienne, Jean-Claude Fignolé, and René Philoctète. While Spiralism has been acknowledged by scholars and regional writer- intellectuals alike as a crucial contribution to the French-speaking Caribbean literary tradition, the Spiralist ethic-aesthetic has not yet been given the sustained attention of a full-length U study. Glover’s book represents the first effort in any language to consider the works of the three Spiralist authors both individually and collectively, and so fills an astonishingly empty NBO place in the assessment of postcolonial Caribbean aesthetics. Touching on the role and destiny of Haiti in the Americas, Haiti Unbound engages with long- standing issues of imperialism and resistance culture in the transatlantic world. Glover’s timely project emphatically articulates Haiti’s regional and global centrality, combining vital ‘big picture’ reflections on the field of postcolonial studies with elegant analyses of the U philosophical perspective and creative practice of a distinctively Haitian literary phenomenon. Most importantly, perhaps, the book advocates for the inclusion of three largely unrecognized ND voices in the disturbingly fixed roster of writer-intellectuals who have thus far interested theorists of postcolonial (francophone) literature. -

(With) Polar Bears in Yoko Tawada'

elizaBetH MCNeill university of Michigan Writing and Reading (with) Polar Bears in Yoko Tawada’s Etüden im Schnee (2014)* Wir betraten tatsächlich ein sphäre, die sich zwischen der der tiere und der der Menschen befand. (Etüden im Schnee 129) in 2016, the kleist Prize was awarded to the Japanese-born yoko tawada, a writer well known in both Japan and Germany for her questioning of national, cultural, and linguistic identities through her distinctly playful style. to open the ceremony, Günter Blamberger reflected on tawada’s adaptations of themes in Heinrich von kleist’s work. Blamberger specifically praised both authors’ creation of liminal beings who not only pass through, but make obsolete the “Grenzen zwischen sprachen, schriften, kulturen, religionen, ländern, zwischen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Mensch und tier, leben und tod” (4). He then highlighted a sample of tawada’s art of transformation, her 2014 novel Etüden im Schnee (translated as Memoirs of a Polar Bear in 2016), which features the narrative voices of three polar bears, much in the style of e.t.a. Hoffmann’s Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1819) and franz kafka’s “ein Bericht für eine akademie” (1917). Upon consid- ering kleist’s use of the bear in his texts, Blamberger simply characterized tawada’s bears as friendly animals who want to understand—and not eat—their human companions. for Blamberger, tawada gives voice not just to these three border-crossing bears and their “Bärensprache,” but more generally to “Misch- und zwischenwesen” in practicing her own migrational literary theory of culture and communication (4). the resulting “Poetik des Dazwischen, der zwischen- zeiten und zwischenräume” foregrounds the metamorphic, even evolutionary, process at work in moving between languages, spaces, cultures, and forms (5). -

The Future of Text and Image

The Future of Text and Image The Future of Text and Image: Collected Essays on Literary and Visual Conjunctures Edited by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh The Future of Text and Image: Collected Essays on Literary and Visual Conjunctures, Edited by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3640-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3640-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface....................................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Image X Text W. J. T. Mitchell PART I: TEXT AND IMAGE IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Chapter One............................................................................................... 15 Portrait of a Secret: J. R. Ackerley and Alison Bechdel Molly Pulda Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 39 PostSecret as Imagetext: The Reclamation of Traumatic Experiences -

MATTERS of RECOGNITION in CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE by JUDITH HEIDI LECHNER a DISSERTATION Presented to the Department Of

MATTERS OF RECOGNITION IN CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE by JUDITH HEIDI LECHNER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of German and Scandinavian and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Judith Heidi Lechner Title: Matters of Recognition in Contemporary German Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of German and Scandinavian by: Susan Anderson Chairperson Michael Stern Core Member Jeffrey Librett Core Member Dorothee Ostmeier Core Member Michael Allan Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2015 ii © 2015 Judith Heidi Lechner This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervis (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Judith Heidi Lechner Doctor of Philosophy Department of German and Scandinavian September 2015 Title: Matters of Recognition in Contemporary German Literature This dissertation deals with current political immigration debates, the conversations about the philosophical concept of recognition, and intercultural encounters in contemporary German literature. By reading contemporary literature in connection with philosophical, psychological, and theoretical works, new problem areas of the liberal promise of recognition become visible. Tied to assumptions of cultural essentialism, language use, and prejudice, one of the main findings of this work is how the recognition process is closely tied to narrative. Particularly within developmental psychology it is often argued that we learn and come to terms with ourselves through narrative. -

Reflections on Exophonic Strategies in Yoko Tawada's Schwager in Bordeaux Flora Roussel

Nomadic Subjectivities: Reflections on Exophonic Strategies in Yoko Tawada’s Schwager in Bordeaux Flora Roussel Department of World’s Literatures and Languages University of Montreal Pavillon Lionel-Groulx, C-8 3150 rue Jean-Brillant Montreal H3T 1N8 Quebec, Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The author Yoko Tawada is well known for her exophonic and experimental work. Writing in German and in Japanese, she joyfully plays with questions of identity, nation-state, culture, language, among other. As exophony in theory and practice is at the center of each of her novels, it thus appears interesting to look closer to the strategies Tawada develops in order to disturb and subvert categorizations. Taking Schwager in Bordeaux as a case study, this paper intends to analyze how Tawada’s exophony de/construct subjectivity. It will first put light on the very concept of exophony, before leaving the space for a close reading analysis of the novel on two specific aspects: dematerialization and rematerialization, which both will aim to draw an exophonic portrait of nomadic writing through its focus on subjectivity. Keywords: Exophony, Subjectivity, Language, Yoko Tawada, Schwager in Bordeaux. Introduction: Marking the Subject/s In response to being asked why she writes not only in German, but also in Japanese, Yoko Tawada [多和田葉子/Tawada Yōko] explains: “I am a bilingual being. I don’t know why exactly, but, for me, it’s inconceivable to stick to only one language.” (Gutjahr 2012, 29; my translation)1 In her portraying a subjectivity navigating offshore, that is, away from monolingualism, the author has created an impressive body of work: since 1987, she has published more than 55 books – approximately half of which are in German, and performed 1170 readings around the world (Tawada 2020, online).