The Future of Text and Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Fun Home: a Family

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic 0 | © 2020 Hope in Box www.hopeinabox.org About Hope in a Box Hope in a Box is a national 501(c)(3) nonprofit that helps rural educators ensure every LGBTQ+ student feels safe, welcome, and included at school. We donate “Hope in a Box”: boxes of curated books featuring LGBTQ+ characters, detailed curriculum for these books, and professional development and coaching for educators. We believe that, through literature, educators can dispel stereotypes and cultivate empathy. Hope in a Box has worked with hundreds of schools across the country and, ultimately, aims to support every rural school district in the United States. Acknowledgements Special thanks to this guide’s lead author, Dr. Zachary Harvat, a high school English teacher with a PhD focusing on 20th and 21st century English literature. Additional thanks to Sara Mortensen, Josh Thompson, Daniel Tartakovsky, Sidney Hirschman, Channing Smith, and Joe English. Suggested citation: Harvat, Zachary. Curriculum Guide for Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Hope in a Box, 2020. For questions or inquiries, email our team at [email protected]. Learn more on our website, www.hopeinabox.org. Terms of use Please note that, by viewing this guide, you agree to our terms and conditions. You are licensed by Hope in a Box, Inc. to use this curriculum guide for non- commercial, educational and personal purposes only. You may download and/or copy this guide for personal or professional use, provided the copies retain all applicable copyright and trademark notices. The license granted for these materials shall be effective until July 1, 2022, unless terminated sooner by Hope in a Box, Inc. -

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics Edited by Michelle Ann Abate, Karly Marie Grice, and Christine N. Stamper In examples ranging from Trina Robbins’s “Sandy Comes Out” in the first issue of Wimmen’s Comix (1972) and Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For series (1986 – 2005) to Diane DiMassa's Hothead Paisan (1991 – 1996) and the recent reboot of DC’s Batwoman (2006 - present), comics have been an important locus of lesbian identity, community, and politics for generations. Accordingly, this special issue will explore the intersection of lesbians and comics. What role have comics played in the cultural construction, social visibility, and political advocacy of same-sex female attraction and identity? Likewise, how have these features changed over time? What is the relationship between lesbian comics and queer comics? In what ways does lesbian identity differ from queer female identity in comics, and what role has the medium played in establishing this distinction as well as blurring, reinforcing, or policing it? Discussions of comics from all eras, countries, and styles are welcome. Likewise, we encourage examinations of comics from not simply literary, artistic, and visual perspectives, but from social, economic, educational, and political angles as well. Possible topics include, but are not limited to: Comics as a locus of representation for lesbian identity, community, and sexuality Analysis of titles featuring lesbian plots, characters, and themes, such as Ariel Schrag’s The High School Chronicles strips, -

Breaking Through Panels: Examining Growth and Trauma in Bechdel's Fun Home and Labelle's Assigned Male Comics

BREAKING THROUGH PANELS: EXAMINING GROWTH AND TRAUMA IN BECHDEL'S FUN HOME AND LABELLE'S ASSIGNED MALE COMICS Katelynn Phillips A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: William Albertini, Advisor Erin Labbie © 2018 Katelynn Phillips All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT William Albertini, advisor Comics featuring LGBTQ children have the burden of challenging cis/heteronormative versions of childhood. Such examples of childhood, according to author Katherine Bond Stockton, are false and restrict children to a vision of innocence that leaves no room for queer children to experience their own versions of childhood. Furthermore, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) community has taken a “progressive”-based approach to time, assuming that newer generations have avoided the trauma of the past because ideas about sexual orientation and gender have advanced with time. Newer generations of the LGBTQ community forget that many have struggled for change to occur, instead choosing to forget the wounds of the past. By analyzing two comic works—Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home and Sophie Labelle’s web comic series Assigned Male—I argue that we must let go of our suspicion towards LGBTQ child characters and open ourselves up to what can be learned from them. I also argue that both the past (with its wounds and trauma) and the future must be accepted into the present in order to give children the childhood they desire, rather than the childhood we recall. Both Fun Home and Assigned Male demonstrate that childhood is far from the simplistic happy time of life and can be just as fraught with complication as adulthood. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

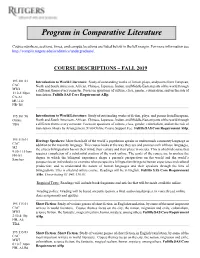

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

FUN BOOKS During COMIC-CON@HOME

FUN BOOKS during COMIC-CON@HOME Color us Covered During its first four years of production (1980–1984), Gay Comix was published by Kitchen Sink Press, a pioneering underground comic book publisher. Email a photo of you and your finished sheet to [email protected] for a chance to be featured on Comic-Con Museum’s social media! Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Anagrams of Class Photo Class Photo is a graphic novella by Gay Comix contributor and editor Robert Triptow. Take 3 minutes and write down words of each size by combining and rearranging the letters in the title. After 3 minutes, tally up your score. How’d you do? 4-LETTER WORDS 5-LETTER WORDS 1 point each 2 points each 6-LETTER WORDS 7-LETTER WORDS 8-LETTER WORDS 3 points each 4 points each 6 points each Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Cross Purpose It’s a crossword and comics history lesson all in one! Learn about cartoonist Howard Cruse, the first editor of the pioneering comic book Gay Comix and 2010 Comic-Con special guest. ACROSS DOWN Share with us! @comicconmuseum #comicconmuseum SPECIAL EDITION 4 Dots & Boxes Minimum 2 players. Take turns connecting two dots horizontally or vertically only; no diagonal lines! When you make a box, write your initials in it, then take another turn. Empty boxes are each worth 1 point. Boxes around works by the listed Gay Comix contributors are each worth 2 points. The player with the most points wins! Watch Out Fun Home Comix Alison Vaughn Frick Bechdel It Ain’t Me Babe Trina Robbins & Willy Mendes subGurlz Come Out Jennifer Comix Camper Mary Wings "T.O. -

History and Background

History and Background Book by Lisa Kron, music by Jeanine Tesori Based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel SYNOPSIS Both refreshingly honest and wildly innovative, Fun Home is based on Vermont author Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir. As the show unfolds, meet Bechdel at three different life stages as she grows and grapples with her uniquely dysfunctional family, her sexuality, and her father’s secrets. ABOUT THE WRITERS LISA KRON was born and raised in Michigan. She is the daughter of Ann, a former community activist, and Walter, a German-born lawyer and Holocaust survivor. Kron spent much of her childhood feeling like an outsider because of her religion and sexuality. She attended Kalamazoo College before moving to New York in 1984, where she found success as both an actress and playwright. Many of Kron’s plays draw upon her childhood experiences. She earned early praise for her autobiographical plays 2.5 Minute Ride and 101 Humiliating Stories. In 1989, Kron co-founded the OBIE Award-winning theater company The Five Lesbian Brothers, a troupe that used humor to produce work from a feminist and lesbian perspective. Her play Well, which she both wrote and starred in, opened on Broadway in 2006. Kron was nominated for the Best Actress in a Play Tony Award for her work. JEANINE TESORI is the most honored female composer in musical theatre history. Upon receiving her degree in music from Barnard College, she worked as a musical theatre conductor before venturing into the art of composing in her 30s. She made her Broadway debut in 1995 when she composed the dance music for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and found her first major success with the off- Broadway musical Violet (Obie Award, Lucille Lortel Award), which was later produced on Broadway in 2014. -

Making the Case for LGBT Graphic Novels Jacqueline Vega Grand Valley State University

Language Arts Journal of Michigan Volume 30 | Issue 2 Article 8 4-2015 Making the Case for LGBT Graphic Novels Jacqueline Vega Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lajm Recommended Citation Vega, Jacqueline (2015) "Making the Case for LGBT Graphic Novels," Language Arts Journal of Michigan: Vol. 30: Iss. 2, Article 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.2070 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language Arts Journal of Michigan by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRACTICE Making the Case for LGBT Graphic Novels JACQUELINE VEGA still remember the exact way my heart was pounding nothing in response. In addition, LGBT students who ex- as I stood in the front of a classroom for the very perienced higher levels of victimization were three times as first time. My senior year of high school, I was of- likely to miss school, have lower GPAs and lower levels of fered the opportunity to lead class lessons for a week self-esteem, and higher levels of depression (NSCS). Per- in a World Literatures class on the graphic novel haps even more disturbing is that less than twenty percent of IAmerican Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang. American Born LGBT students were taught positive representations about Chinese (2006), a text that has become increasingly popular the LGBT community, and that nearly fifteen percent of stu- in English classrooms, tells a story of two teenage boys, one dents had been taught negative content (NSCS, my emphasis). -

Queer As Folklore: How Fun Home Destabilizes the Metronormative Myth

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Dean James E. McLeod Freshman Writing Prize Student Scholarship 2018 Queer as Folklore: How Fun Home Destabilizes the Metronormative Myth Grace MacArthur Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mcleod Recommended Citation MacArthur, Grace, "Queer as Folklore: How Fun Home Destabilizes the Metronormative Myth" (2018). Dean James E. McLeod Freshman Writing Prize. 5. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mcleod/5 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dean James E. McLeod Freshman Writing Prize by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Queer as Folklore: How Fun Home Destabilizes the Metronormative Myth Imagine a queer person. Imagine what they look like and how they move through space. Now imagine the spaces they move through: where they work, where they go, and where they live. You are constructing a queer geography around your individual, who likely moves through crowded streets, coffee shops, concerts, and dark bars illuminated by weak neon. Our communal conceptualization of queer experience in modern-day America, especially as recorded in queer media, skews heavily towards urban geographies. The constituent “imaginative processes associated with gay migration from rural and suburban areas to cities” (Weston 256) continually construct and reinforce a hegemonic “discourse of metronormativity” (Sander 28) from which an imaginary narrative has emerged. The narrative mythologizes urban/rural as a strict binary and systematically privileges the urban above the rural. -

YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

VON DER MUTTERSPRACHE ZUR SPRACHMUTTER: YOKO TAWADA’S CREATIVE MULTILINGUALISM AN EXHIBITION ON THE OCCASION OF YOKO TAWADA’S VISIT TO OXFORD AS DAAD WRITER IN RESIDENCE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, TAYLORIAN (VOLTAIRE ROOM) HILARY TERM 2017 ExhiBition Catalogue written By Sheela Mahadevan Edited By Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann and Chantal Wright Contributed to by Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann, Chantal Wright, Emma HuBer and ChriStoph Held Photo of Yoko Tawada Photographer: Takeshi Furuya Source: Yoko Tawada 1 Yoko Tawada’s Biography: CABINET 1 Yoko Tawada was born in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan. She began to write as a child, and at the age of twelve, she even bound her texts together in the form of a first book. She learnt German and English at secondary school, and subsequently studied Russian literature at Waseda University in 1982. After this, she intended to go to Russia or Poland to study, since she was interested in European literature, especially Russian literature. However, her university grant to study in Poland was withdrawn in 1980 because of political unrest, and instead, she had the opportunity to work in Hamburg at a book trade company. She came to Europe by ship, then by trans-Siberian rail through the Soviet Union, Poland and the DDR, arriving in Berlin. In 1982, she studied German literature at Hamburg University, and thereafter completed her doctoral work on literature at Zurich University. Among various authors, she studied the poetry of Paul Celan, which she had already read in Japanese. Indeed, she comments on his poetry in an essay entitled ‘Paul Celan liest Japanisch’ in her collection of essays named Talisman and also in her essay entitled ‘Die Niemandsrose’ in the collection Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte.