YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 28 Issue 1 Writing and Reading Berlin Article 10 1-1-2004 Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Anke Biendarra University of Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Biendarra, Anke (2004) "Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1574 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Abstract In March 1999, critic Volker Hage adopted a term in Der Spiegel that subsequently dominated public discussions about new German literature by female authors-"Fräuleinwunder"… Keywords 1999, Volker Hage, Der Spiegel, new German literature, female authors, Fräuleinwunder, Julia Franck, Judith Hermann, critic, gender, generation This article is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol28/iss1/10 Biendarra: Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Anke S. Biendarra University of Cincinnati In March 1999, critic Volker Hage adopted a term in Der Spiegel that subsequently dominated public discussions about new Ger- man literature by female authors-"Frauleinwunder."' He uses it collectively for "the young women who make sure that German literature is again a subject of discussion this spring." Hage as- serts that they seem less concerned with "the German question," the consequences of two German dictatorships, and prefer in- stead to thematize "eroticism and love" in their texts. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, begiiming at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9211205 Redeeming history in the story: Narrative strategies in the novels of Anna Seghers and Nadine Gordimer Prigan, Carol Ludtke, Ph.D. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

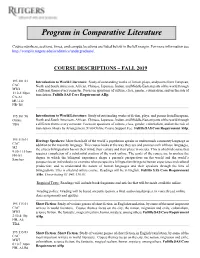

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

Das Große Balladenbuch

Otfried Preußler Heinrich Pleticha Das große Balladenbuch Mit Bildern von Friedrich Fiechelmann Inhaltsübersicht Nicht nur »Theaterstücke im Kleinen« Eine Einführung in die Balladen von Heinrich Pleticha................................................. h Es IST SCHON SPÄT, ES WIRD SCHON KALT Durch die Balladen im Volkston fuhrt Otfried Preußler................................................... 15 Heinrich Heine: Lorelei ................................................................................................. 17 Clemens Brentano: Lore Lay.......................................................................................... 17 Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff: Waldgespräch............................................................ 19 Eduard Mörike: Zwei Liebchen...................................................................................... 20 Volksballade: Der Wassermann...................................................................................... 21 Agnes Miegel: Schöne Agnete........................................................................................ 23 Franz Karl Ginzkey: Ballade vom gastlichen See ......................................................... 25 Gottfried August Bürger: Lenore.................................................................................... 26 Volksballade: Lenore (aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn) ................................................... 35 Hans Watzlik: Der Tänzer.............................................................................................. -

Lektürevorschläge Für Den Epochenorientierten Unterricht Übersicht Zu Den Im Bildungsplan Vorgegebenen Epochen Und Texten

Lektürevorschläge für den epochenorientierten Unterricht Übersicht zu den im Bildungsplan vorgegebenen Epochen und Texten lassik Gedichte (z.B. Goethes Venezianische Epigramme und Römische Elegien, Goethes !Merkmale# und Schillers Xenien) , Drama (z.B. Goethes Iphigenie auf Tauris), Epos (z.B. Goethes Reineke Fuchs) $ %oethe: Faust I 'omantik Eichendor(: Das Marmorbild !Merkmale# Gedichte (z.B. Günderrode, Brentano, Eichendorff, Mörike, No!alis, von Arnim, #hland, Hauff, Tieck etc.) " utoren& 'urzprosa (z.B. Märchen der Grimms oder von Hauff), Erzählun)* o!elle (z.B: Adel+ert von Chamisso: Peter Schlemihls wundersame !eschichte, E.T.A. Hoffmann&"er Sandmann) " utorinnen& Bettina von Arnim, Karoline Günderrode, Therese Hu+er, Sophie La Roche, Sophie Mereau*Brentano, Dorothea Schle)el/Schellin) (0 Te1te au2 guten+er).de) Literatur der Gedichte (z.B. Rilke, Geor)e, Ho2mannsthal, Huch, Mor)enstern etc.) )ahrhundert*ende "utorinnen& !Merkmale+# * .omane (z.B. -ou "ndreas/Salom3& "as #aus, .icarda $uch& "er Fall "eruga, 4ranziska zu .e!entlo5& #errn "ames $ufzeichnungen, Bertha !on Suttner& "ie %a&en nieder', Gabriele Reuter& Aus guter Familie) Erzählun)en* o!ellen (z.B. Marie !on E+ner/Eschen+ach& (ram)am)uli, "as !emeindekin ) "utoren& .omane (z.B. Thomas Mann: *udden)r++ks, Königliche H+heit, Heinrich Mann: Pr+fessor Unrat, Der Untertan) o!elle/Erzählun) (z.B. Gerhart Hauptmann: *ahnw-rter Thiel, %homas Mann& "er T+d in Venedig, Schnitzler: Traumn+.elle, Z5ei): *rennendes Geheimnis) Dramen (z.B. Gerhart $auptmann& "ie Ratten, "er *i)erpelz, "ie %e)er, Schnitzler& Reigen, Wedekind& Fr/hlings Erwachen) Moderne Mann: Mario und der Zauberer Brecht: Leben des Galilei Bachmann: Der gute Gott von Manhattan Gedichte, Kurzprosa %egen*artsliteratur -eethaler: Der Trafikant ,Literatur der Jahrhundert*ende 8 (Realismus) 8 aturalismus (s.o.) → Re2erate . -

30 April 2015

Weekly Round-Up, 30 April 2015 * Any weekly round-up attachments can be found at the following link https://weblearn.ox.ac.uk/access/content/group/modlang/general/weekly_roundup/index.html Disclaimer: The University of Oxford and the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages accept no responsibility for the content of any advertisement published in The Weekly Round-Up. Readers should note that the inclusion of any advertisement in no way implies approval or recommendation of either the terms of any offer contained in it or of the advertiser by the University of Oxford or The Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages. Contents 1 Lectures and Events Internal 1.1 How to Write the Great War? Francophone and Anglophone Poetics 1.2 OCGH events update: Tuesday 28 April, 2pm-6.30pm, St Antony's 1.3 DANSOX Events 1.4 Post-Kantian European Philosophy Seminar (PKEPS): Trinity Term 2015 1.5 Part of an endless river: Alberto de Lacerda – A Commemorative Exhibition 1.6 Intensive Weekend Courses at the Language Centre 1.7 The Archive and Forms of Knowledge seminar series : Carolyn Steedman 1.8 Bodleian Libraries Workshop for Week 2 1.9 Oxford Travel Cultures Seminar: 'Travel and Consumption' Programme 1.10 Oxford Podemos Talk 1.11 Dante at 750, Looking Back With Auerbach, Oxford, 5 June 2015 1.12 Clara Florio Cooper Memorial Lecture 2015 1.13 Liberal Limits of Liberalism: Saturday 2nd May 2015 1.14 OCGH and the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine: 'Disease and Global History' Workshop 1.15 OCGH Events Update 1.16 Events Organised by the Maison Française -

Temporality, Subjectivity and Postcommunism in Contemporary German Literature by Herta Müller, Zsuzsa Bánk and Terézia Mora

PASTS WITH FUTURES: TEMPORALITY, SUBJECTIVITY AND POSTCOMMUNISM IN CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE BY HERTA MÜLLER, ZSUZSA BÁNK AND TERÉZIA MORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katrina Louise Nousek May 2015 © 2015 Katrina Louise Nousek PASTS WITH FUTURES: TEMPORALITY, SUBJECTIVITY AND POSTCOMMUNISM IN CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE BY HERTA MÜLLER, ZSUZSA BÁNK AND TERÉZIA MORA Katrina Louise Nousek, Ph. D. Cornell University 2015 This dissertation analyzes future-oriented narrative features distinguishing German literature about European communism and its legacies. Set against landscapes marked by Soviet occupation and Ceauşescu’s communist dictatorship in Romania (Müller) and against the 1956 Hungarian revolution, eastern European border openings, and post-Wende Berlin (Mora, Bánk), works by these transnational authors engage social legacies that other discourses relegate to an inert past after the historic rupture of 1989. Dominant scholarship reads this literature either through trauma theory or according to autobiography, privileging national histories and static cultural identities determined by the past. Shifting attention to complex temporal structures used to narrate literary subjectivities, I show how these works construct European futures that are neither subsumed into a homogeneous present, nor trapped in traumatic repetition, nostalgic longing, or psychic disavowal. My analysis extends and contributes to debates in politics and the arts about the status of utopia after communism and the role of society in political entities no longer divided in Cold War terms of East/West, three worlds, or discrete national cultures. By focusing on Müller, Mora and Bánk, I widen the purview of FRG-GDR discussions about communism to include transnational, temporal and narrative perspectives that scholarship on these authors often overlooks. -

Farocki/Godard: Film As Theory 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Volker Pantenburg Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3558 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Pantenburg, Volker: Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3558. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/32375 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FAROCKI/ GODARD FILM AS THEORY volker pantenburg Farocki/Godard Farocki/Godard Film as Theory Volker Pantenburg Amsterdam University Press The translation of this book is made possible by a grant from Volkswagen Foundation. Originally published as: Volker Pantenburg, Film als Theorie. Bildforschung bei Harun Farocki und Jean-Luc Godard, transcript Verlag, 2006 [isbn 3-899420440-9] Translated by Michael Turnbull This publication was supported by the Internationales Kolleg für Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. IKKM BOOKS Volume 25 An overview of the whole series can be found at www.ikkm-weimar.de/schriften Cover illustration (front): Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Chapter 4B (1988-1998) Cover illustration (back): Interface © Harun Farocki 1995 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press.