(With) Polar Bears in Yoko Tawada'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

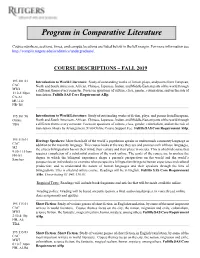

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

VON DER MUTTERSPRACHE ZUR SPRACHMUTTER: YOKO TAWADA’S CREATIVE MULTILINGUALISM AN EXHIBITION ON THE OCCASION OF YOKO TAWADA’S VISIT TO OXFORD AS DAAD WRITER IN RESIDENCE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, TAYLORIAN (VOLTAIRE ROOM) HILARY TERM 2017 ExhiBition Catalogue written By Sheela Mahadevan Edited By Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann and Chantal Wright Contributed to by Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann, Chantal Wright, Emma HuBer and ChriStoph Held Photo of Yoko Tawada Photographer: Takeshi Furuya Source: Yoko Tawada 1 Yoko Tawada’s Biography: CABINET 1 Yoko Tawada was born in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan. She began to write as a child, and at the age of twelve, she even bound her texts together in the form of a first book. She learnt German and English at secondary school, and subsequently studied Russian literature at Waseda University in 1982. After this, she intended to go to Russia or Poland to study, since she was interested in European literature, especially Russian literature. However, her university grant to study in Poland was withdrawn in 1980 because of political unrest, and instead, she had the opportunity to work in Hamburg at a book trade company. She came to Europe by ship, then by trans-Siberian rail through the Soviet Union, Poland and the DDR, arriving in Berlin. In 1982, she studied German literature at Hamburg University, and thereafter completed her doctoral work on literature at Zurich University. Among various authors, she studied the poetry of Paul Celan, which she had already read in Japanese. Indeed, she comments on his poetry in an essay entitled ‘Paul Celan liest Japanisch’ in her collection of essays named Talisman and also in her essay entitled ‘Die Niemandsrose’ in the collection Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte. -

The Future of Text and Image

The Future of Text and Image The Future of Text and Image: Collected Essays on Literary and Visual Conjunctures Edited by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh The Future of Text and Image: Collected Essays on Literary and Visual Conjunctures, Edited by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Ofra Amihay and Lauren Walsh and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3640-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3640-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface....................................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Image X Text W. J. T. Mitchell PART I: TEXT AND IMAGE IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY Chapter One............................................................................................... 15 Portrait of a Secret: J. R. Ackerley and Alison Bechdel Molly Pulda Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 39 PostSecret as Imagetext: The Reclamation of Traumatic Experiences -

MATTERS of RECOGNITION in CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE by JUDITH HEIDI LECHNER a DISSERTATION Presented to the Department Of

MATTERS OF RECOGNITION IN CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE by JUDITH HEIDI LECHNER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of German and Scandinavian and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Judith Heidi Lechner Title: Matters of Recognition in Contemporary German Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of German and Scandinavian by: Susan Anderson Chairperson Michael Stern Core Member Jeffrey Librett Core Member Dorothee Ostmeier Core Member Michael Allan Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2015 ii © 2015 Judith Heidi Lechner This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDervis (United States) License. iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Judith Heidi Lechner Doctor of Philosophy Department of German and Scandinavian September 2015 Title: Matters of Recognition in Contemporary German Literature This dissertation deals with current political immigration debates, the conversations about the philosophical concept of recognition, and intercultural encounters in contemporary German literature. By reading contemporary literature in connection with philosophical, psychological, and theoretical works, new problem areas of the liberal promise of recognition become visible. Tied to assumptions of cultural essentialism, language use, and prejudice, one of the main findings of this work is how the recognition process is closely tied to narrative. Particularly within developmental psychology it is often argued that we learn and come to terms with ourselves through narrative. -

Reflections on Exophonic Strategies in Yoko Tawada's Schwager in Bordeaux Flora Roussel

Nomadic Subjectivities: Reflections on Exophonic Strategies in Yoko Tawada’s Schwager in Bordeaux Flora Roussel Department of World’s Literatures and Languages University of Montreal Pavillon Lionel-Groulx, C-8 3150 rue Jean-Brillant Montreal H3T 1N8 Quebec, Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The author Yoko Tawada is well known for her exophonic and experimental work. Writing in German and in Japanese, she joyfully plays with questions of identity, nation-state, culture, language, among other. As exophony in theory and practice is at the center of each of her novels, it thus appears interesting to look closer to the strategies Tawada develops in order to disturb and subvert categorizations. Taking Schwager in Bordeaux as a case study, this paper intends to analyze how Tawada’s exophony de/construct subjectivity. It will first put light on the very concept of exophony, before leaving the space for a close reading analysis of the novel on two specific aspects: dematerialization and rematerialization, which both will aim to draw an exophonic portrait of nomadic writing through its focus on subjectivity. Keywords: Exophony, Subjectivity, Language, Yoko Tawada, Schwager in Bordeaux. Introduction: Marking the Subject/s In response to being asked why she writes not only in German, but also in Japanese, Yoko Tawada [多和田葉子/Tawada Yōko] explains: “I am a bilingual being. I don’t know why exactly, but, for me, it’s inconceivable to stick to only one language.” (Gutjahr 2012, 29; my translation)1 In her portraying a subjectivity navigating offshore, that is, away from monolingualism, the author has created an impressive body of work: since 1987, she has published more than 55 books – approximately half of which are in German, and performed 1170 readings around the world (Tawada 2020, online). -

Introduction to German Literature

Introduction to German Literature Course Number GERM-UA 9152 D01 Fall 2019 Syllabus last updated on: 29-7-2019 Lecturer Contact Information Course PD Dr. Elke Brüns [email protected] Details Tuesday 10:00am to 12:45pm Location: Rooms will be posted in Albert before your first class. Please double check whether your class takes place at the Academic Center (BLAC – Schönhauser Allee 36, 10435 Berlin) or at St. Agnes (SNTA – Alexandrinenstraße 118-121, 10969 Berlin). Prerequisites Intermediate German II. Furthermore, it is strongly recommended that students also take Composition & Conversation before taking this class. Units earned 4 Course Description Der Kurs führt in die Geschichte der deutschen Literatur vom 18. Jahrhundert bis in die Gegenwart ein. Anhand repräsentativer Werke vermittelt er einen Überblick über zentrale Epochen und Gattungen, erste literaturwissenschaftliche Fachbegriffe werden erläutert. Kontinuitäten und Brüche, die als signifikante Entwicklungslinien oder Zäsuren die Literaturgeschichte markieren, werden im historischen und gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhang diskutiert. Der Kurs beinhaltet Exkursionen innerhalb Berlins, zudem werden wir mit einer Autorin über Gegenwartsliteratur diskutieren. Der Kurs wird durchgängig in deutscher Sprache unterrichtet. This course provides an introduction to the history of German Literature from the 18th century up until the present. By reading representative texts, students will receive an overview of various epochs and genres. In addition, the basic terminology of literary studies will be explained. Continuities and disruptions that have significantly influenced the history of literature will be discussed in their historical and social contexts. Some Sessions will be held outside the classroom, and we will discuss with an author about contemporary literature. The class will be taught entirely in German. -

Yoko Tawada's Novel Memoirs of a Polar Bear

Between “East” and “West”: Goethe’s World Literature, the Question of Nation, and the Postnational in Yoko Tawada’s Novel Memoirs of a Polar Bear Monika Leipelt-Tsai* ABSTRACT Goethe had established a literary connection between “Europe” and the “Orient” in his West-Östlicher Divan (West-East Divan). His idea of “world literature” can be reframed when it is linked by Homi K. Bhabha with the cosmopolitan: “the study of world literature might be the study of the way in which cultures recognize themselves through their projections of ‘otherness.’” The contemporary author Yoko Tawada is from East Asia and has been writing poems, prose, and plays in German and in Japanese. In her playful way of writing, she explores the interrela- tionship between “Western” and “Eastern” cultures, thereby translating them in cross-border poetics. Using the method of constellation, we examine the question of nation and the postnational in Goethe and Tawada alongside Bhabha, and propose to read Tawada’s novel Memoirs of a Polar Bear as “world literature” in light of how the transnational migrants’ perspective becomes literally difficult to place. KEYWORDS world literature, Goethe, West-Eastern Divan, Yoko Tawada, Memoirs of a Polar Bear, the national Ex-position, Issue No. 45, June 2021 | National Taiwan University DOI: 10.6153/EXP.202106_(45).0009 Monika LEIPELT-TSAI, Associate Professor, Department of European Languages and Cultures, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 141 Goethe’s World Literature Yoko Tawada, born in 1960 in Tokyo, is a postnational writer who lives in Berlin, Germany and travels the world. She is already famous, and, among other prizes, in 2017 she received the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation for Memoirs of Ex-position a Polar Bear, together with the translator Susan Bernofsky. -

"Nur Durch Begriffe Kann Man Beides Voneinander Trennen"

"Nur durch Begriffe kann man beides voneinander trennen" Zum produktiven Verhältnis von Theorie und Literatur in Yoko Tawadas deutschsprachigem Werk Masterarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Master of Arts (MA) an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Michaela MAYER am Institut für Germanistik Begutachterin: Univ.-Prof. Dr.phil. Anne-Kathrin Reulecke Graz, 2015 Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die den Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbe- hörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. Graz, am 17.08.2015 Michaela Mayer „Wenn ich von mehreren Realitäten, die nebeneinander existieren, sprechen würde, müsste ich davon ausgehen, dass jede Realität für sich steht. […] Was aber, wenn sie alle aus Wasser bestehen würden?“ (Yoko Tawada, Fremde Wasser, S. 55) Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Verwandlungen : Tawadas Tübinger Poetik-Vorlesungen .................................................. 5 2.1 Einführende Bemerkungen: Tawada und die Gattung ‚Poetikvorlesung‘ ........................ 5 2.2 Die erste Vorlesung: -

Institut Für Germanistik II - Neuere Deutsche Literatur

Institut für Germanistik II - Neuere deutsche Literatur K O M M E N T I E R T E S V O R L E S U N G S V E R Z E I C H N I S Sommersemester 2011 Stand: 16. März 2011 2 ggggg "Hamburger Gastprofessur für Interkulturelle Poetik" im SoSe 2011 Konzeption und Leitung: Prof. Dr. Ortrud Gutjahr Lehrstuhl für Neuere deutsche Literatur und Interkulturelle Literaturwissenschaft In diesem Sommersemester wird zum ersten Mal die von der ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius geförderte "Hamburger Gastprofessur für Interkulturelle Poetik" vergeben. Mit der Einrichtung dieser besonderen Poetikprofessur wird die Bedeutung der deutschsprachigen in- terkulturellen Literatur gewürdigt und das Selbstverständnis Hamburgs als weltoffene Stadt 'beim Wort' genommen. Eingeladen werden renommierte Autor/inn/en, die sich mit kulturdif- ferenten Erfahrungshorizonten und Wertorientierungen in ihren Werken beschäftigen und für die literarische Gestaltung von tiefgreifenden Veränderungsprozessen wie beispielsweise infol- ge von Migration, Mauerfall und Globalisierung neue Ausdrucksformen finden. Sie setzen sich in ihren Vorlesungen im Rahmen der Gastprofessur an der Universität Hamburg mit dem Po- tential der ästhetischen Inszenierung von Interkulturalität auseinander und stellen zusätzlich an verschiedenen Orten der Stadt - am Hafen, im Literaturhaus, im Theater - themenzentriert ihre literarischen Texte vor, um sowohl mit Studierenden als auch der interessierten Öffentlichkeit ins Gespräch zu kommen. Dabei wird es unweigerlich auch um Ideen zu einer kosmopoliti- schen Kultur gehen, in der die Auseinandersetzung mit Interkulturalität zentrale Bedeutung für ein neues Miteinander gewinnt. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Yoko Tawada Die erste "Gastprofessur für Interkulturelle Poetik" an der Universität Hamburg geht im Sommerseme- ster 2011 an Yoko Tawada, die unserer Stadt in be- sonderer Weise verbunden ist.