2020 Aldous Grahame 160470

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Semaphore Circular No 679 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2018

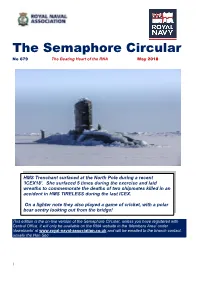

The Semaphore Circular No 679 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2018 HMS Trenchant surfaced at the North Pole during a recent ‘ICEX18’. She surfaced 5 times during the exercise and laid wreaths to commemorate the deaths of two shipmates killed in an accident in HMS TIRELESS during the last ICEX. On a lighter note they also played a game of cricket, with a polar bear sentry looking out from the bridge! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec 1 Daily Orders (follow each link) Orders [follow each link] 1. 2018 Dublin Conference 2. Finance Corner 3. RNVC Surgeon William Job Maillard VC 4. Joke – Golfing 5. Charity Donations 6. Guess Where 7. Branch and Recruitment and Retention Advisor 8. Conference 2019 – Wyboston Lakes 9. Veterans Gateway and Preserved Pensions 10. Assistance Request Please 11. HMS Gurkha Assistance 12. Can you Assist – HMS Arethusa 13. RNAS Yeovilton Air Day 14. HMS Collingwood Open Day 15. HMS Bristol EGM 16. Association of Wrens NSM Visit 17. Pembroke House Annual Garden Party 18. Joke – Small Cricket Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy -

HMS EAGLE for Those Who Served in Her, but Many Others Will Read It: Wives, Parents, Sweethearts and Friends

Introduction This is a book about HMS EAGLE for those who served in her, but many others will read it: wives, parents, sweethearts and friends. To those who do, may I suggest that you concentrate on reading between the lines. If you do this you will recognise at once the labour of love which the compilation of this book entailed. You will also recognise that here is the last saga of a Great Ship, prepared to fight if needed, prepared to aid anyone in distress, prepared to represent her country honourably on all occasions and in all parts of the world. In the many photographs you can meet the men of EAGLE, no less a band of brothers than the men of Nelson's ships. Between the lines in this book, with its frequent understatement, you will find an anatomy of the Royal Navy revealed in the character, courage, fortitude, humour and kindliness of EAGLE's officers and men. EDITOR'S NOTE - We regret that this souvenir book is in `paperback' form, but by sacrificing hard covers we have been able to include a lot more material than would otherwise have been possible with the money available. Should you wish for a copy bound in boards, then, it is quite easy to get this done by any bookbinder - it would not be very expensive. (For those of you in possession of the book of the first half of the commission, from 5 March 1969, the two could be bound together.) The author of the book of the first part of this last commission concluded by saying, `We'll be back'. -

British Commemorative Medals

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Gold Medals 2074 Victoria, Golden Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by L C Wyon, after Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and (reverse), Sir Frederick Leighton, crowned and veiled bust left, rev the Queen enthroned with figures of the arts and industry around her, 58mm, 89.86g, in red leather case of issue (BHM 3219). Extremely fine, damage to clasp of case. £900-1100 944 specimens struck, selling at 13 Guineas each 2075 Victoria, Diamond Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by G W -

Chapter 2. the Slender Thread Cast Off: Migration & Reception

The Slender Thread Chapter 2 Willeen Keough Chapter 2 The Slender Thread Cast Off Migration and Reception in Newfoundland When Michael and Mary Ryan were coming from County Wexford Ireland to Nfld. their first child was Born at sea. It was the year 1826. The boy was named Thomas Ryan… Michael Ryan… was drowned near Petty Harbour Motion, in the year 1830 on a sealing voyage. His wife Mary Ryan was left with 3 young children, Thomas who was born at sea, Michael and Thimothy Ryan. After some years Mary Ryan Married again. Edward Coady also a native of County Wexford. They had a family of 2 sons and 1 daughter… They have many decendents at Cape Broyle, many places in Canada and also in the United States. Audio Sample These homespun words, transcribed from the oral tradition by an elderly community historian in 1971, provide a skeletal story of an Irish woman who came to Cape Broyle on the southern Avalon in the early nineteenth century.1 It is a sparse and plainspoken chronicle of her life, but Mary Ryan's story could be the stuff of movie directors' dreams. A young Irish woman leaves her home in Wexford to accompany her husband on a perilous journey that will bring her to a landscape quite different from the green farmlands of her home country. There has been some urgency in their leaving, for Mary is well into her pregnancy upon departure, and the transatlantic crossing, difficult at best, will be a dangerous venture for a woman about to give birth. -

Jabberwock No 85

BERWO JAB CK The Magazine of the Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum IN THISIN THIS EDITION: EDITION: • Memoirs of Captain Keith Leppard and Sqn Ldr Maurice Biggs • Peter Twiss • Christmas Lunch notice • Hawker Sea Fury detail • The first angled deck • HMS Engadine at theBattle of Jutland • Society Visit to the Meteorological Office • Book Review - “Air War in the Mediterranean” PLUS: All the usual features; news from the Museum, snippets from Council meetings, monthly talks programme, latest membership numbers... No. 85 November 2016 No. 85 November 2016 Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 Patron: Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN President: Gordon Johnson FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM RNAS Yeovilton Somerset BA22 8HT Telephone: 01935 840565 SOFFAAM email: [email protected] SOFFAAM website: fleetairarmfriends.org.uk Registered Charity No. 280725 Sunset - HMS Illustrious 1 Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Admission Vice Presidents Members are admitted to the Museum Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN free of charge, on production of a valid F C Ott DSC BSc (Econ) membership card. Members may be Lt Cdr Philip (Jan) Stuart RN accompanied by up to three guests (one David Kinloch guest only for junior members) on any Derek Moxley one visit, each at a reduced entrance Gerry Sheppard fee, currently 50% of the standard price. Members are also allowed a 10% Bill Reeks discount on goods purchased from the shop. -

The Mammoth Cave ; How I

OUTHBERTSON WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 Mails. Publications : The Mammoth Cave ; D'ACHE, Caran (Emmanuel Poire), cari- How I found the Gainsborough Picture ; caturist b. in ; Russia ; grandfather French Conciliation in the North of Coal ; England ; grandmother Russian. Drew political Mine to Cabinet ; Interviews from Prince cartoons in the "Figaro; Caran D'Ache is to Peasant, etc. Recreations : cycling, Russian for lead pencil." Address : fchological studies. Address : 33 Walton Passy, Paris. [Died 27 Feb. 1909. 1 ell Oxford. Club : Koad, Oxford, Reform. Sir D'AGUILAR, Charles Lawrence, G.C.B ; [Died 2 Feb. 1903. cr. 1887 ; Gen. b. 14 (retired) ; May 1821 ; CUTHBERTSON, Sir John Neilson ; Kt. cr, s. of late Lt.-Gen. Sir George D'Aguilar, 1887 ; F.E.I.S., D.L. Chemical LL.D., J.P., ; K.C.B. d. and ; m. Emily, of late Vice-Admiral Produce Broker in Glasgow ; ex-chair- the Hon. J. b. of of School Percy, C.B., 5th Duke of man Board of Glasgow ; member of the Northumberland, 1852. Educ. : Woolwich, University Court, Glasgow ; governor Entered R. 1838 Mil. Sec. to the of the Glasgow and West of Scot. Technical Artillery, ; Commander of the Forces in China, 1843-48 ; Coll. ; b. 13 1829 m. Glasgow, Apr. ; Mary served Crimea and Indian Mutiny ; Gen. Alicia, A. of late W. B. Macdonald, of commanding Woolwich district, 1874-79 Rammerscales, 1865 (d. 1869). Educ. : ; Lieut.-Gen. 1877 ; Col. Commandant School and of R.H.A. High University Glasgow ; Address : 4 Clifton Folkestone. Coll. Royal of Versailles. Recreations: Crescent, Clubs : Travellers', United Service. having been all his life a hard worker, had 2 Nov. -

Freedom by Reaching the Wooden World: American Slaves and the British Navy During the War of 1812

Freedom by Reaching the Wooden World: American Slaves and the British Navy during the War of 1812. Thomas Malcomson Les noirs américains qui ont échappé à l'esclavage pendant la guerre de 1812 l'ont fait en fuyant vers les navires de la marine britannique. Les historiens ont débattu de l'origine causale au sein de cette histoire, en la plaçant soit entièrement dans les mains des esclaves fugitifs ou les Britanniques. L'historiographie a mis l'accent sur l'expérience des réfugiés dans leur lieu de réinstallation définitive. Cet article réexamine la question des causes et se concentre sur la période comprise entre le premier contact des noirs américains qui ont fuit l'esclavage et la marine britannique, et le départ définitif des ex-esclaves avec les Britanniques à la fin de la guerre. L'utilisation des anciens esclaves par les Britanniques contre les Américains en tant que guides, espions, troupes armées et marins est examinée. Les variations locales en l'interaction entre les esclaves fugitifs et les Britanniques à travers le théâtre de la guerre, de la Chesapeake à la Nouvelle-Orléans, sont mises en évidence. As HMS Victorious lay at anchor in Lynnhaven Bay, off Norfolk, in the early morning hours of 10 March 1813, a boat approached from the Chesapeake shore.1 Its occupants, nine American Black men drew the attention of the sailors in the guard boat circling the 74 gun ship. The men were runaway slaves. After a cautious inspection, the guard boat’s crew towed them to the Victorious where the nine Black men climbed up the ship’s side and entered freedom. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Ajax New Past up For

H.M.S. Ajax & River Plate Veterans Association NEWSLETTER SEPTEMBER 2017 CONTENTS Chairman's Remarks Newsletter Editor's Remarks Standard Bearer's Report The Longest Tow Memories of the Falklands Conflict– Glyn Seagrave Commemorative Plate Membership Secretary's Report With obituary: Ted Wicks Sale of Ajax to Chile – Clive Sharplin Garden Party – Dan Sherren Ajax Cleaner Road to Salvation Mike Cranswick – Ajax Visit 7th Astute Submarine Name Captain Peter Cobb – Obituary Graf Spee eagle Crossing the Line – Follow up Barnard Court Ajax Charlie Maggs & Joe Collis News from Town of Ajax – Colleen Jordan Roy Turner - Birthday Party 1975 Times of Malta article Archivist Report Separate Sheet 2017 AGM Agenda NEC QUISQUAM NISI AJAX 2. 3. H.M.S. AJAX & RIVER PLATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION. CHAIRMAN/SECRETARY ARCHIVIST/WEBMASTER/ NEWSLETTER EDITOR REPORT Peter Danks NEWSLETTER EDITOR Thanks to everyone who contributed material for this Newsletter. If you do see any material in 104 Kelsey Avenue Malcolm Collis any way connected to Ajax, sailors, the sea or similar, that you think may be interesting or Southbourne The Bewicks, Station Road humorous please send it to me. Emsworth Ten Mile Bank, Even though the Newsletters are only every three months it soon comes round and again a holiday Hampshire PO10 8NQ Norfolk PE38 0EU near the issue date has meant a rushed end. Tel: 01243 371947 Tel: 01366 377945 [email protected] [email protected] Talking of holidays; I haven't done too much on the 2019 South America trip this period as I have been waiting to see what comes out of the Reunion AGM when we debate it. -

Archaeological Research on HMS Swift: a British Sloop-Of- War Lost Off Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770

The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2007) 36.1: 32–58 doi: 10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00117.x ArchaeologicalBlackwellDOLORESNAUTICAL Publishing ELKIN ARCHAEOLOGY ETLtd AL.: ARCHAEOLOGICAL 35.2 RESEARCH ON HMS SWIFT: LOST OFF PATAGONIA, 1770 research on HMS Swift: a British Sloop-of- War lost off Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770 Dolores Elkin CONICET—Programa de Arqueología Subacuática, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 3 de Febrero 1378 (1426) Buenos Aires, Argentina Amaru Argüeso, Mónica Grosso, Cristian Murray and Damián Vainstub Programa de Arqueología Subacuática, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 3 de Febrero 1378 (1426) Buenos Aires, Argentina Ricardo Bastida CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Funes 3320 (7600) Mar del Plata, Argentina Virginia Dellino-Musgrave English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Eastney, Portsmouth, PO4 9LD, UK HMS Swift was a British sloop-of-war which sank off the coast of Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770. Since 1997 the Underwater Archaeology Programme of the National Institute of Anthropology has taken charge of the archaeological research conducted at the wreck-site. This article presents an overview of the continuing Swift project and the different research lines comprised in it. The latter cover aspects related to ship-construction, material culture and natural site-formation processes. © 2006 The Authors Key words: maritime archaeology, HMS Swift, 18th-century shipwreck, Argentina, ship structure, biodeterioration. t 6 p.m. on 13 March 1770 a British Royal Over two centuries later, in 1975, an Australian Navy warship sank off the remote and called Patrick Gower, a direct descendant of A barren coast of Patagonia, in the south- Lieutenant Erasmus Gower of the Swift, made a western Atlantic. -

Michael H. Clemmesen Version 6.10.2013

Michael H. Clemmesen Version 6.10.2013 1 Prologue: The British 1918 path towards some help to Balts. Initial remarks to the intervention and its hesitant and half-hearted character. It mirrored the situation of governments involved in the limited interventions during the last In the conference paper “The 1918-20 International Intervention in the Baltic twenty years. Region. Revisited through the Prism of Recent Experience” published in Baltic Security and Defence Review 2:2011, I outlined a research and book project. The This intervention against Bolshevik Russia and German ambitions would never Entente intervention in the Baltic Provinces and Lithuania from late 1918 to early have been reality without the British decision to send the navy to the Baltic 1920 would be seen through the prism of the Post-Cold War Western experience Provinces. The U.S. would later play its strangely partly independent role, and the with limited interventions, from Croatia and Bosnia to Libya, motivated by the operation would not have ended as it did without a clear a convincing French wish to build peace, reduce suffering and promote just and effective effort. However, the hesitant first step originated in London. government. This first part about the background, discourse and experience of the first four months of Britain’s effort has been prepared to be read as an independent contribution. However, it is also an early version of the first chapters of the book.1 It is important to note – especially for Baltic readers – that the book is not meant to give a balanced description of what we now know happened. -

City of St. John's Archives the Following Is a List of St. John's

City of St. John’s Archives The following is a list of St. John's streets, areas, monuments and plaques. This list is not complete, there are several streets for which we do not have a record of nomenclature. If you have information that you think would be a valuable addition to this list please send us an email at [email protected] 18th (Eighteenth) Street Located between Topsail Road and Cornwall Avenue. Classification: Street A Abbott Avenue Located east off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Abbott's Road Located off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Aberdeen Avenue Named by Council: May 28, 1986 Named at the request of the St. John's Airport Industrial Park developer due to their desire to have "oil related" streets named in the park. Located in the Cabot Industrial Park, off Stavanger Drive. Classification: Street Abraham Street Named by Council: August 14, 1957 Bishop Selwyn Abraham (1897-1955). Born in Lichfield, England. Appointed Co-adjutor Bishop of Newfoundland in 1937; appointed Anglican Bishop of Newfoundland 1944 Located off 1st Avenue to Roche Street. Classification: Street Adams Avenue Named by Council: April 14, 1955 The Adams family who were longtime residents in this area. Former W.G. Adams, a Judge of the Supreme Court, is a member of this family. Located between Freshwater Road and Pennywell Road. Classification: Street Adams Plantation A name once used to identify an area of New Gower Street within the vicinity of City Hall. Classification: Street Adelaide Street Located between Water Street to New Gower Street. Classification: Street Adventure Avenue Named by Council: February 22, 2010 The S.