Chapter 2. the Slender Thread Cast Off: Migration & Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018

Municipal Backyard Compost Bin Program Participants 2011-Present 2018 Baie Verte Bay St George Waste Management Committee Cape St George Channel Port au Basques City of St John's Gander Greens Habour Lourdes New-Wes-Valley Northern Peninsula Regional Service Board Paradise Pasadena Sandy Cove Trinity Bay North Twillingate 2017 Baie Verte Carbonear Corner Brook Farm and Market, Clarenville Grand Falls-Windsor Logy Bay-Middle Cove-Outer Cove Makkovik Memorial University, Grenfell Campus Paradise Pasadena Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Robert's Arm Sandy Cove St. Lawrence St. John's Twillingate 2016 2015 Brigus Baie Verte Burin Corner Brook Carmanville Discovery Regional Service Board Comfort Cove - New Stead Happy Valley - Goose Bay Fogo Island Logy Bay - Middle Cove - Outer Cove Gambo Sandy Cove Gander St. John's McIver’s Sunnyside North West River Witless Bay Point Leamington 2014 Burgeo Carbonear Conception Bay South (CBS) Lewisporte Paradise Portugal Cove - St. Phillip’s St. Alban’s St. Anthony (NorPen Regional Service Board) St. George’s St. John's Whitbourne Witless Bay 2013 Bird Cove Kippens Bishop's Falls Lark Harbour Campbellton Marystown Clarenville New Perlican Conception Bay South (CBS) NorPen Regional Service Board Conne River Old Perlican Corner Brook Paradise Deer Lake Pasadena Dover Placentia Flatrock Port au Choix Gambo Portugal Cove-St. Phillips Grand Bank Springdale Happy Valley - Goose Bay Stephenville Harbour Grace Twillingate 2011 Botwood Conception Bay South (CBS) Cape Broyle Conception Harbour Gander Conne River Glovertown Corner Brook Sunnyside Deer Lake Harbour Main – Chapel’s Cove – Gambo Lakeview Glenwood Holyrood Grand Bank Logy Bay Harbour Breton Appleton Heart’s Delight - Islington Arnold’s Cove Irishtown – Summerside Bay Roberts Kippens Baytona Labrador City Bonavista Lawn Campbellton Leading Tickles Carbonear Long Harbour & Mount Arlington Centreville Heights Channel - Port aux Basques Makkovik (Labrador) Colliers Marystown 2011 cont. -

Geology Map of Newfoundland

LEGEND POST-ORDOVICIAN OVERLAP SEQUENCES POST-ORDOVICIAN INTRUSIVE ROCKS Carboniferous (Viséan to Westphalian) Mesozoic Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and minor carbonate rocks; intercalated marine, Gabbro and diabase siliciclastic, carbonate and evaporitic rocks; minor coal beds and mafic volcanic flows Devonian and Carboniferous Devonian and Carboniferous (Tournaisian) Granite and high silica granite (sensu stricto), and other granitoid intrusions Fluviatile and lacustrine sandstone, shale, conglomerate and minor carbonate rocks that are posttectonic relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and carbonate rocks; subaerial, bimodal Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks; may include some Late Silurian rocks Gabbro and diorite intrusions, including minor ultramafic phases Silurian and Devonian Posttectonic gabbro-syenite-granite-peralkaline granite suites and minor PRINCIPAL Shallow marine sandstone, conglomerate, limey shale and thin-bedded limestone unseparated volcanic rocks (northwest of Red Indian Line); granitoid suites, varying from pretectonic to syntectonic, relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies (southeast of TECTONIC DIVISIONS Silurian Red Indian Line) TACONIAN Bimodal to mainly felsic subaerial volcanic rocks; includes unseparated ALLOCHTHON sedimentary rocks of mainly fluviatile and lacustrine facies GANDER ZONE Stratified rocks Shallow marine and non-marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, including Cambrian(?) and Ordovician 0 150 sandstone, shale and conglomerate Quartzite, psammite, -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts: Exchanges Between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767

Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture General Editor Karl A.E. Enenkel (Chair of Medieval and Neo-Latin Literature Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster e-mail: kenen_01@uni_muenster.de) Editorial Board W. van Anrooij (University of Leiden) W. de Boer (Miami University) Chr. Göttler (University of Bern) J.L. de Jong (University of Groningen) W.S. Melion (Emory University) R. Seidel (Goethe University Frankfurt am Main) P.J. Smith (University of Leiden) J. Thompson (Queen’s University Belfast) A. Traninger (Freie Universität Berlin) C. Zittel (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice / University of Stuttgart) C. Zwierlein (Freie Universität Berlin) volume 74 – 2021 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/inte Exile, Diplomacy and Texts Exchanges between Iberia and the British Isles, 1500–1767 Edited by Ana Sáez-Hidalgo Berta Cano-Echevarría LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. This volume has been benefited from financial support of the research project “Exilio, diplomacia y transmisión textual: Redes de intercambio entre la Península Ibérica y las Islas Británicas en la Edad Moderna,” from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, the Spanish Research Agency (Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad). -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

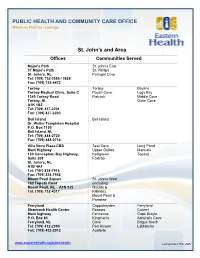

St. John's and Area

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY CARE OFFICE Where to Find Us - Listings St. John’s and Area Offices Communities Served Major’s Path St. John’s East 37 Major’s Path St. Phillips St. John’s, NL Portugal Cove Tel: (709) 752-3585 / 3626 Fax: (709) 752-4472 Torbay Torbay Bauline Torbay Medical Clinic, Suite C Pouch Cove Logy Bay 1345 Torbay Road Flatrock Middle Cove Torbay, NL Outer Cove A1K 1B2 Tel: (709) 437-2201 Fax: (709) 437-2203 Bell Island Bell Island Dr. Walter Templeton Hospital P.O. Box 1150 Bell Island, NL Tel: (709) 488-2720 Fax: (709) 488-2714 Villa Nova Plaza-CBS Seal Cove Long Pond Main Highway Upper Gullies Manuels 130 Conception Bay Highway, Kelligrews Topsail Suite 208 Foxtrap St. John’s, NL A1B 4A4 Tel: (70(0 834-7916 Fax: (709) 834-7948 Mount Pearl Square St. John’s West 760 Topsail Road (including Mount Pearl, NL A1N 3J5 Goulds & Tel: (709) 752-4317 Kilbride), Mount Pearl & Paradise Ferryland Cappahayden Ferryland Shamrock Health Center Renews Calvert Main highway Fermeuse Cape Broyle P.O. Box 84 Kingman’s Admiral’s Cove Ferryland, NL Cove Brigus South Tel: (709) 432-2390 Port Kirwan LaManche Fax: (709) 432-2012 Auaforte www.easternhealth.ca/publichealth Last updated: Feb. 2020 Witless Bay Main Highway Witless Bay Burnt Cove P.O. Box 310 Bay Bulls City limits of St. John’s Witless Bay, NL Bauline to Tel: (709) 334-3941 Mobile Lamanche boundary Fax: (709) 334-3940 Tors Cove but not including St. Michael’s Lamanche. Trepassey Trepassey Peter’s River Biscay Bay Portugal Cove South St. -

Archaeological Research on HMS Swift: a British Sloop-Of- War Lost Off Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770

The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2007) 36.1: 32–58 doi: 10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00117.x ArchaeologicalBlackwellDOLORESNAUTICAL Publishing ELKIN ARCHAEOLOGY ETLtd AL.: ARCHAEOLOGICAL 35.2 RESEARCH ON HMS SWIFT: LOST OFF PATAGONIA, 1770 research on HMS Swift: a British Sloop-of- War lost off Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770 Dolores Elkin CONICET—Programa de Arqueología Subacuática, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 3 de Febrero 1378 (1426) Buenos Aires, Argentina Amaru Argüeso, Mónica Grosso, Cristian Murray and Damián Vainstub Programa de Arqueología Subacuática, Instituto Nacional de Antropología, 3 de Febrero 1378 (1426) Buenos Aires, Argentina Ricardo Bastida CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Funes 3320 (7600) Mar del Plata, Argentina Virginia Dellino-Musgrave English Heritage, Fort Cumberland, Eastney, Portsmouth, PO4 9LD, UK HMS Swift was a British sloop-of-war which sank off the coast of Patagonia, Southern Argentina, in 1770. Since 1997 the Underwater Archaeology Programme of the National Institute of Anthropology has taken charge of the archaeological research conducted at the wreck-site. This article presents an overview of the continuing Swift project and the different research lines comprised in it. The latter cover aspects related to ship-construction, material culture and natural site-formation processes. © 2006 The Authors Key words: maritime archaeology, HMS Swift, 18th-century shipwreck, Argentina, ship structure, biodeterioration. t 6 p.m. on 13 March 1770 a British Royal Over two centuries later, in 1975, an Australian Navy warship sank off the remote and called Patrick Gower, a direct descendant of A barren coast of Patagonia, in the south- Lieutenant Erasmus Gower of the Swift, made a western Atlantic. -

AMC ADVENTURE TRAVEL Volunteer-Led Excursions Worldwide

AMC ADVENTURE TRAVEL Volunteer-Led Excursions Worldwide Newfoundland – Hike and Explore the East Coast Trail June 18 - 28, 2022 Trip #2248 Cape Spear, Newfoundland (photo from Wikipedia), Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Trip Overview Are you looking for a hiking adventure that combines experiencing spectacular coastal trails, lighthouses, sea spouts, a boat tour with bird sightings, and potential whales and iceberg viewing? Or enjoy a morning kayaking around a bay? Sounds exciting, then come join us on our Newfoundland Adventure to hike parts of the East Coast Trail, explore and enjoy the spectacular views from the most eastern point of North America. Birds love Newfoundland and we will have the opportunity to see many. Newfoundland is known as the Seabird Capital of North America and Witless Bay Reserve boasts the largest colony of the Atlantic Puffin. Other birds we may see are: Leach’s Storm Petrels, Common Murre, Razorbill, Black Guillemot, and Black-legged Kittiwake, to name a few. Newfoundland is one of the most spectacular places on Earth to watch whales. The world’s largest population of Humpback whales returns each year along the coast of Newfoundland and an additional 21 species of whales and dolphins visit the area. We will have potential to see; Minke, Sperm, Pothead, Blue, and Orca whales. Additionally we will learn about its history, enjoy fresh seafood and walk around the capital St. John’s. This will be an Adventure that is not too far from our northern border. -

City of St. John's Archives the Following Is a List of St. John's

City of St. John’s Archives The following is a list of St. John's streets, areas, monuments and plaques. This list is not complete, there are several streets for which we do not have a record of nomenclature. If you have information that you think would be a valuable addition to this list please send us an email at [email protected] 18th (Eighteenth) Street Located between Topsail Road and Cornwall Avenue. Classification: Street A Abbott Avenue Located east off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Abbott's Road Located off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Aberdeen Avenue Named by Council: May 28, 1986 Named at the request of the St. John's Airport Industrial Park developer due to their desire to have "oil related" streets named in the park. Located in the Cabot Industrial Park, off Stavanger Drive. Classification: Street Abraham Street Named by Council: August 14, 1957 Bishop Selwyn Abraham (1897-1955). Born in Lichfield, England. Appointed Co-adjutor Bishop of Newfoundland in 1937; appointed Anglican Bishop of Newfoundland 1944 Located off 1st Avenue to Roche Street. Classification: Street Adams Avenue Named by Council: April 14, 1955 The Adams family who were longtime residents in this area. Former W.G. Adams, a Judge of the Supreme Court, is a member of this family. Located between Freshwater Road and Pennywell Road. Classification: Street Adams Plantation A name once used to identify an area of New Gower Street within the vicinity of City Hall. Classification: Street Adelaide Street Located between Water Street to New Gower Street. Classification: Street Adventure Avenue Named by Council: February 22, 2010 The S. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.