Downloaded from Brill.Com09/26/2021 12:44:54AM Via Free Access 206 K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop Edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt

Achaemenid History • II The Greek Sources Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Leiden 1987 ACHAEMENID HISTORY 11 THE GREEK SOURCES PROCEEDINGS OF THE GRONINGEN 1984 ACHAEMENID HISTORY WORKSHOP edited by HELEEN SANCISI-WEERDENBURG and AMELIE KUHRT NEDERLANDS INSTITUUT VOOR HET NABIJE OOSTEN LEIDEN 1987 © Copyright 1987 by Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Witte Singe! 24 Postbus 9515 2300 RA Leiden, Nederland All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Greek The Greek sources: proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid history workshop / ed. by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amelie Kuhrt. - Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.- (Achaemenid history; II) ISBN90-6258-402-0 SISO 922.6 UDC 935(063) NUHI 641 Trefw.: AchaemenidenjPerzische Rijk/Griekse oudheid; historiografie. ISBN 90 6258 402 0 Printed in Belgium TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations. VII-VIII Amelie Kuhrt and Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg INTRODUCTION. IX-XIII Pierre Briant INSTITUTIONS PERSES ET HISTOIRE COMPARATISTE DANS L'HIS- TORIOGRAPHIE GRECQUE. 1-10 P. Calmeyer GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY AND ACHAEMENID RELIEFS. 11-26 R.B. Stevenson LIES AND INVENTION IN DEINON'S PERSICA . 27-35 Alan Griffiths DEMOCEDES OF CROTON: A GREEKDOCTORATDARIUS' COURT. 37-51 CL Herrenschmidt NOTES SUR LA PARENTE CHEZ LES PERSES AU DEBUT DE L'EM- PIRE ACHEMENIDE. 53-67 Amelie Kuhrt and Susan Sherwin White XERXES' DESTRUCTION OF BABYLONIAN TEMPLES. 69-78 D.M. Lewis THE KING'S DINNER (Polyaenus IV 3.32). -

Medievaia Coinage

~) June 11, 1993 Classical Numismatic Group, Inc will sell at public and mail bid auction the exceptional collection of Greek Gold & Electrum assembled by George & Robert Stevenson This collection features ovel" 150 pieces. Pedigrees of the Ste\'enson coins r('ad like a "who's who" or great collectors durin!,: the past century, with coins from the collections of Pozzi, Virzi, Hrand, Garrell, Weber, Ryan, llaron Pennisi di'Floristella, Hauer, Bement, Castro Maya, Warren, Greenwell, N.wille, several museum collections and others In addition to the Stevenson Collection, this SOlie includes a sup erb ofrering of Greek silver and bronze, Roman including a collection of SeslerW, Byzantine. Medieval and Uritish coins. Classical Numismatic Group Auction XXVI In Conjunction with the 2nd Annual Spring New York International Friday June II, 1993 at 6PM Sheraton New York Hotcl & Towers Catalogues are available for $151£10 CLASSICAL NUMISMATIC GROUP, INC ~ Post Office Box 245 ~Quarryville, Pennsylvania 17566-0245 " • (717) 786-4013, FAX (717) 786-7954 • SEABY COINS ~ 7 Davies Street ~London, WIY ILL United Kingdom (071) 495-1888, FAX (071) 499-5916 INSIDE THE CELATOR ... Vol. 7, NO.5 FEATURES May 1993 6 A new distater of Alexander 'lJieCefatoT by Harlan J. Berk Publisher/Senior Editor 10 Slavery and coins Wayne G. Sayles in the Roman world Office Manager Janet Sayles by Marvin Tameanko Editor Page 6 18 The Scipio legend: Steven A. Sayles A new distater of Alexander A question of portraiture Marketi ng Director by Harlan J. Berk Stephanie Sayles by Todd Kirkby RCCLiaison J ames L. Meyer 32 The arms of Godfrey of Boullion and the Production Asst. -

Classical Studies Transition Year Unit

Classical Studies Transition Year Unit A Manual for Teachers This manual was created by Dr Bridget Martin, with the invaluable support of Dr Christopher Farrell and Ms Tasneem Filaih, on behalf of UCD Access Classics. UCD Access Classics (Dr Bridget Martin, Ms Tasneem Filaih and Dr Christopher Farrell) wish to thank the following for their kind help with and support of this Unit: Dr Alexander Thein, Dr Louise Maguire, Ms Claire Nolan, Dr Jo Day, Dr Aude Doody, Ms Michelle McDonnell, the UCD School of Classics (under the headship of Dr Alexander Thein and, since July 2020, Dr Martin Brady) and the NCCA. Image source for front cover: Coin 1: RRC 216/1 (2249). Reproduced with the kind permission of the UCD Classical Museum. ClassicalCoin 2: RRCStudies: 385/4 Transition (2135). Reproduced Year Unit with the ki nd permission of the UCD Classical Museum. Table of Contents UNIT DESCRIPTOR ............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 1: What is Classical Studies? A case study of Ancient Cyprus .............. 7 Table quiz ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Language ........................................................................................... 10 1.2 Art and artefacts: Mosaics in the House of Dionysus ................................ 13 1.3 Mythology: Aphrodite.......................................................................... -

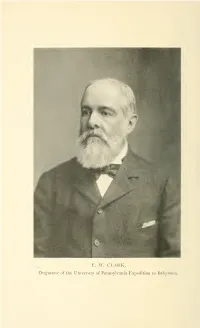

Nippur; Or, Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; The

E. \V. CLARK. Originator of the University of Pennsylvania Expedition to Babylonia. NIPPUR OR EXPLORATIONS AND ADVENTURES ON THE EUPHRATES THE NARRATIVE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA EXPEDITION TO BABYLONIA IN THE YEARS 1888-1890 BY JOHN PUNNETT PETERS, PH.D., Sc.D., D.D. Director of the Expedition WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS VOLUME 1. FIRST CAMPAIGN SECOND EDITION G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON i,\t llnickcrbocktt ^rcss i8q8 Copyright, 1897 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube Iktiicherbocfter iPress, IRew jgorft To THE Public-Spirited Gentlemen OF Philadelphia WHO MADE THE EXPEDITION POSSIBLE THESE Volumes are Respectfully Dedicated PREFACE. No city in this country has shown an interest in archeol- ogy at all comparable with that displayed by Philadelphia, A group of public-spirited gentlemen in that city has given without stint time and money for explorations in Babylonia, Egypt, Central America, Italy, Greece, and our own land ; and has, within the last ten years amassed archaeological col- lections which are unsurpassed in this country. The first im- portant work undertaken was the Babylonian Expedition. As described in the Narrative, this expedition was inaugurated by a Philadelphia banker, Mr. E. W. Clark. The enterprise was taken up in its infancy by the University of Pennsylvania, under the lead of its provost, Dr. William Pepper. Dr. Pepper made this expedition and the little band of men who liad become interested in it the nucleus for further enterprises. A library and museum were built, an Archaeological Associa- tion was formed, and a band of men was gathered together in Philadelphia who have contributed with a liberality and en- thusiasm quite unparalleled for the prosecution of archaeologi- cal research in almost all parts of the world. -

This Book — the Only History of Friendship in Classical Antiquity That Exists in English

This book — the only history of friendship in classical antiquity that exists in English - examines the nature of friendship in ancient Greece and Rome from Homer (eighth century BC) to the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century AD. Although friendship is throughout this period conceived of as a voluntary and loving relationship (contrary to the prevailing view among scholars), there are major shifts in emphasis from the bonding among warriors in epic poetry, to the egalitarian ties characteristic of the Athenian democracy, the status-con- scious connections in Rome and the Hellenistic kingdoms, and the commitment to a universal love among Christian writers. Friendship is also examined in relation to erotic love and comradeship, as well as for its role in politics and economic life, in philosophical and religious communities, in connection with patronage and the private counsellors of kings, and in respect to women; its relation to modern friendship is fully discussed. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEYTHEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY Friendship in the classical world Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEY THEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY EDITORS Dr P. -

Diodorus Siculus

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.b.hist.soc. FORMER EDITORS fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LiTT.D. fE. CAPPS, ph.d., ll.d. tW. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. L. A. POST, l.h.d. DIODORUS OF SICILY II 303 DIODOEUS OF SICILY IN TWELVE VOLUMES II BOOKS II {continued) 35-IV, 58 WITH AN EXGLISH TRANSLATION BY C. H. OLDFATHER PROFESSOR OP AKCIENT HISTORY AND LANGUAGES, THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBR.\SKA LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXVn First printed 1935 Reprinted 1953, 1961, 1967 y rn 0-4 .^5^7/ Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION TO BOOKS II, 35-IV, 58 . vii BOOK II (continued) 1 BOOK III 85 BOOK IV, 1-58 335 A PARTIAL INDEX OF PROPER NAMES .... 535 MAPS 1. ASIA At end 2. AEGYPTUS-ETHIOPIA „ ; INTRODUCTION Books II, 35-IV, 58 Book II, 35^2 is devoted to a brief description of India which was ultimately derived from Megasthenes. Although Diodorus does not mention this author, his use of him is established by the similarity between his account of India and the Indica of Arrian and the description of that land by Strabo, both of whom avowedly drew their material from that ^vTiter. Megasthenes was in the service of Seleucus Nicator and in connection with embassies to the court of king Sandracottus (Chandragupta) at Patna was in India for some time between 302 and 291 b.c. In his Indica in four Books he was not guilty of the romances of Ctesias, but it is plain that he was imposed upon by inter- preters and guides, as was Herodotus on his visit to Egypt. -

Ancient Engineers' Inventions

Ancient Engineers’ Inventions HISTORY OF MECHANISM AND MACHINE SCIENCE Vo l u m e 8 Series Editor MARCO CECCARELLI Aims and Scope of the Series This book series aims to establish a well defined forum for Monographs and Pro- ceedings on the History of Mechanism and Machine Science (MMS). The series publishes works that give an overview of the historical developments, from the earli- est times up to and including the recent past, of MMS in all its technical aspects. This technical approach is an essential characteristic of the series. By discussing technical details and formulations and even reformulating those in terms of modern formalisms the possibility is created not only to track the historical technical devel- opments but also to use past experiences in technical teaching and research today. In order to do so, the emphasis must be on technical aspects rather than a purely historical focus, although the latter has its place too. Furthermore, the series will consider the republication of out-of-print older works with English translation and comments. The book series is intended to collect technical views on historical developments of the broad field of MMS in a unique frame that can be seen in its totality as an En- cyclopaedia of the History of MMS but with the additional purpose of archiving and teaching the History of MMS. Therefore the book series is intended not only for re- searchers of the History of Engineering but also for professionals and students who are interested in obtaining a clear perspective of the past for their future technical works. -

Ancient Greek Unitary Systems and Their Evolution from Earlier Systems of Measurement

ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: ELE2018-0014 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series ELE2018-0014 Athens, 12 October 2018 Ancient Dimensions and Units: Ancient Greek Unitary Systems and their Evolution from Earlier Systems of Measurement Scott Grenquist Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10683 Athens, Greece ATINER’s conference paper proceedings series are circulated to promote dialogue among academic scholars. All papers of this series have been blind reviewed and accepted for presentation at one of ATINER’s annual conferences according to its acceptance policies (http://www.atiner.gr/acceptance). © All rights reserved by authors. 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: ELE2018-0014 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series ELE2018-0014 Athens, 12 October 2018 ISSN: 2529-167X Scott Grenquist, Associate Professor, Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA Ancient Dimensions and Units: Ancient Greek Unitary Systems and their Evolution from Earlier Systems of Measurement ABSTRACT From 900 BCE to 323 BCE, the ancient Greek civilization advanced in all forms of science, economics, politics and art. During this time period, everything would change in the life of the average Greek citizen. Only 300 years prior, the Mycenaean civilization had collapsed, and a Greek Dark Age had descended over all of ancient Greek society. During the beginning of that Dark Age, as the Mycenaean empire collapsed, literacy and numeracy skills still existed, but were sequestered in literate scribes that were grouped into guilds, and were attached to the Mycenaean palaces that still existed throughout the Greek mainland and in Crete. As the Greek Dark Age progressed, even those guilds of scribes disappeared forever from Greek society. -

UCD Access Classics Transition Year Unit for Teacher 2020

Classical Studies Transition Year Unit A Manual for Teachers This manual was created by Dr Bridget Martin, with the invaluable support of Dr Christopher Farrell and Ms Tasneem Filaih, on behalf of UCD Access Classics. UCD Access Classics wish to thank the following for their kind help with and support of this Unit: Dr Alexander Thein, Dr Louise Maguire, Ms Claire Nolan, Dr Jo Day, Dr Aude Doody, Ms Michelle McDonnell, the UCD School of Classics (under the headship of Dr Alexander Thein and, since July 2020, Dr Martin Brady) and the NCCA. Image source for front cover: Coin 1: RRC 216/1 (2249). Reproduced with the kind permission of the UCD Classical Museum. ClassicalCoin 2: RRCStudies: 385/4 Transition (2135). Reproduced Year Unit with the ki nd permission of the UCD Classical Museum. Table of Contents UNIT DESCRIPTOR ............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 1: What is Classical Studies? A case study of Ancient Cyprus .............. 7 Table quiz ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Language ........................................................................................... 10 1.2 Art and artefacts: Mosaics in the House of Dionysus ................................ 13 1.3 Mythology: Aphrodite........................................................................... 16 1.4 History .............................................................................................. -

Philip II and Alexander the Great: Father and Son, Lives and Afterlives

PHILIP II AND ALEXANDER THE GREAT This page intentionally left blank Philip II and Alexander the Great Father and Son, Lives and Afterlives Edited by ELIZABETH CARNEY and DANIEL OGDEN 2010 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philip II and Alexander the Great : father and son, lives and afterlives/ edited by Elizabeth Carney and Daniel Ogden. p. cm. A selection from the papers presented at an international symposium, “Philip II and Alexander III: Father, Son and Dunasteia,” held April 3-5, 2008, at Clemson University, in South Carolina. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-973815-1 1. Philip II, King of Macedonia, 382–336 B.C.—Congresses. 2. Alexander, the Great, 356-323 B.C.—Congresses. -

The Complete List of Measurement Units Supported

28.3.2019 The Complete List of Units to Convert The List of Units You Can Convert Pick one and click it to convert Weights and Measures Conversion The Complete List of Measurement Units Supported # A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z # ' (minute) '' (second) Common Units, Circular measure Common Units, Circular measure % (slope percent) % (percent) Slope (grade) units, Circular measure Percentages and Parts, Franctions and Percent ‰ (slope permille) ‰ (permille) Slope (grade) units, Circular measure Percentages and Parts, Franctions and Percent ℈ (scruple) ℔, ″ (pound) Apothecaries, Mass and weight Apothecaries, Mass and weight ℥ (ounce) 1 (unit, point) Apothecaries, Mass and weight Quantity Units, Franctions and Percent 1/10 (one tenth or .1) 1/16 (one sixteenth or .0625) Fractions, Franctions and Percent Fractions, Franctions and Percent 1/2 (half or .5) 1/3 (one third or .(3)) Fractions, Franctions and Percent Fractions, Franctions and Percent 1/32 (one thirty-second or .03125) 1/4 (quart, one forth or .25) Fractions, Franctions and Percent Fractions, Franctions and Percent 1/5 (tithe, one fifth or .2) 1/6 (one sixth or .1(6)) Fractions, Franctions and Percent Fractions, Franctions and Percent 1/7 (one seventh or .142857) 1/8 (one eights or .125) Fractions, Franctions and Percent Fractions, Franctions and Percent 1/9 (one ninth or .(1)) ångström Fractions, Franctions and Percent Metric, Distance and Length °C (degrees Celsius) °C (degrees Celsius) Temperature increment conversion, Temperature increment Temperature scale -

Encyclopaedia of Scientific Units, Weights and Measures Their SI Equivalences and Origins

FrancËois Cardarelli Encyclopaedia of Scientific Units, Weights and Measures Their SI Equivalences and Origins English translation by M.J. Shields, FIInfSc, MITI 13 Other Systems 3 of Units Despite the internationalization of SI units, and the fact that other units are actually forbidden by law in France and other countries, there are still some older or parallel systems remaining in use in several areas of science and technology. Before presenting conversion tables for them, it is important to put these systems into their initial context. A brief review of systems is given ranging from the ancient and obsolete (e.g. Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Old French) to the relatively modern and still in use (e.g. UK imperial, US customary, cgs, FPS), since a general knowledge of these systems can be useful in conversion calculations. Most of the ancient systems are now totally obsolete, and are included for general or historical interest. 3.1 MTS, MKpS, MKSA 3.1.1 The MKpS System The former system of units referred to by the international abbreviations MKpS, MKfS, or MKS (derived from the French titles meÁtre-kilogramme-poids-seconde or meÁtre-kilo- gramme-force-seconde) was in fact entitled SysteÁme des MeÂcaniciens (Mechanical Engi- neers' System). It was based on three fundamental units, the metre, the second, and a weight unit, the kilogram-force. This had the basic fault of being dependent on the acceleration due to gravity g, which varies on different parts of the Earth, so that the unit could not be given a general definition. Furthermore, because of the lack of a unit of mass, it was difficult, if not impossible to draw a distinction between weight, or force, and mass (see also 3.4).