Brill's Companion to the Reception of Sophocles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee's Iphigenia

An Examination of the Correlation Between the Justification and Glorification of War in Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0: A Director’s Approach Caroline Donica Table of Contents Chapter One: Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 4 Introduction 4 The Life and Works of Charles Mee 4 Just War 8 Production History and Reception 11 Survey of Literature 13 Conclusion 15 Chapter Two: Play Analysis 16 Introduction 16 Synopsis 16 Given Circumstances 24 Previous Action 26 Dialogue and Imagery 27 Character Analysis 29 Idea and Theme 34 Conclusion 36 Chapter Three: The Design Process 37 Introduction 37 Production Style 37 Director’s Approach 38 Choice of Stage 38 Collaboration with Designers 40 Set Design 44 Costumes 46 Makeup and Hair 50 Properties 52 Lighting 53 Sound 55 Conclusion 56 Chapter Four: The Rehearsal Process 57 Introduction 57 Auditions and Casting 57 Rehearsals and Acting Strategies 60 Technical and Dress Rehearsals 64 Performances 65 Conclusion 67 Chapter Five: Reflection 68 Introduction 68 Design 68 Staging and Timing 72 Acting 73 Self-Analysis 77 Conclusion 80 Appendices 82 A – Photos Featuring the Set Design 83 B – Photos Featuring the Costume Design 86 C – Photos Featuring the Lighting Design 92 D – Photos Featuring the Concept Images 98 Works Consulted 102 Donica 4 Chapter One Charles Mee and the History Behind Iphigenia 2.0 Introduction Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0 is a significant work in recent theatre history. The play was widely recognized and repeatedly produced for its unique take on contemporary issues, popular culture, and current events set within a framework of ancient myths and historical literature. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

European Academic Research

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. II, Issue 9/ December 2014 Impact Factor: 3.1 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org Condemned to be Free: Orestes in Sartre’s The Flies MOHSIN HASSAN KHAN Research Scholar Department of English A.M.U., Aligarh, India Abstract: Jean Paul Sartre’s Orestes’ is one of the strong characters as far as literary sketch of any existential character is concerned. Embodiment of Sartrean philosophy, Orestes, in the play The Flies (1943) is a representation of the philosophy of freedom in which Sartre has put his literary thesis with the philosophic. In doing so with the character of Orestes, he comes back again to his lifelong pursuit of freedom and tries to explore it in the most possible and natural sense making freedom as an absolute and a strong value. The idea of freedom has been smoothly sketched in the play and its strident treatment matches the doctrines of freedom by the playwright. In this play, Sartre expresses the idea of condemned freedom and an attempt has been made in this paper to show this particular Sartrean brand of freedom expressed in Orestes. Key words: Existentialism, Existence, Freedom, Condemned, Absolute, No. Enlightenment Jean Paul Sartre, an avowed existentialist and a militant atheist, being at the centre of the modern philosophy is a very important figure in French existentialism. Truly a philosopher in the traditional sense like Heidegger and also a political figure protesting in the student’s revolution of 1968 in which he was almost close to becoming a rebel, he is a fine amalgamation of 20th century thought in which letters and actions go together 11954 Mohsin Hassan Khan- Condemned to be Free: Orestes in Sartre’s The Flies simultaneously. -

Reflections of Anglo-Saxon England

Reflections of Anglo-Saxon England Exhibit Checklist Department of Special Collections | 976 Memorial Library University of Wisconsin–Madison | 728 State Street http://specialcollections.library.wisc.edu/ Exhibit July through September 2011 in conjunction with the biennial conference of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists ©2011 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Image: Saxon chief from Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, The costume of the original inhabitants of the British islands (London, 1815). Thordarson Collection Reflections of Anglo-Saxon England This exhibit in the Department of Special Collections explores the history, artifacts, and myths of Anglo-Saxon England and their many political and cultural uses. Featuring printed books from the 16th century through the present, the exhibit is designed to complement the biennial conference of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists in Madison in summer 2011. Books on display, as listed here, highlight reflections of (and on) Anglo-Saxon England, including renderings of language of the period, depictions of archaeological finds, chronicles of the Christianization of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and accounts — whether sober or fanciful — of custom, dress, and battle. The impetus for the exhibit came from now professor emeritus John D. Niles, president in 2011 of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, who also brought numerous exhibit-worthy titles to our attention. The exhibit’s curator was Lynnette Regouby, dissertator in the Department of History of Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was able to uncover many an illustrated treasure among the holdings of Special Collections, Memorial Library, and other campus libraries. Exhibit installation was the work of staff members and student assistants in Special Collections, especially Barbara Richards, Susan Stravinski, Steven Lange, Lotus Norton-Wisla, Rachael Page, Crystal Schmidt, and Alex Sorensen. -

ELECTRA by Sophocles Translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS in THE

ELECTRA by Sophocles translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY ORESTES, son of Agamemnon and CLYTEMNESTRA ELECTRA } sister of ORESTES CHRYSOTHEMIS} " " " AN OLD MAN, formerly the PAEDAGOGUS or Attendant Of ORESTES CLYTEMNESTRA AEGISTHUS CHORUS OF WOMEN OF MYCENAE Mute Persons PYLADES, son of Strophius, King of Crisa, the friend Of ORESTES. A handmaid of CLYTEMNESTRA. Two attendants of ORESTES ELECTRA ELECTRA (SCENE:- At Mycenae, before the palace of the Pelopidae. It is morning and the new-risen sun is bright. The PAEDAGOGUS enters on the left of the spectators, accompanied by the two youths, ORESTES and PYLADES.) PAEDAGOGUS SON of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon!- now thou mayest behold with thine eyes all that thy soul hath desired so long. There is the ancient Argos of thy yearning,- that hallowed scene whence the gadfly drove the daughter of Inachus; and there, Orestes, is the Lycean Agora, named from the wolf-slaying god; there, on the left, Hera's famous temple; and in this place to which we have come, deem that thou seest Mycenae rich in gold, with the house of the Pelopidae there, so often stained with bloodshed; whence I carried thee of yore, from the slaying of thy father, as thy kinswoman, thy sister, charged me; and saved thee, and reared thee up to manhood, to be the avenger of thy murdered sire. Now, therefore, Orestes, and thou, best of friends, Pylades, our plans must be laid quickly; for lo, already the sun's bright ray is waking the songs of the birds into clearness, and the dark night of stars is spent. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

Existentialism in Two Plays of Jean-Paul Sartre

Journal of English and Literature Vol. 3(3), 50-54, March 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL DOI:10.5897/IJEL11.042 ISSN 2141-2626 ©2012 Academic Journals Review Existentialism in two plays of Jean-Paul Sartre Cagri Tugrul Mart Department of Languages, Ishik University, Erbil, Iraq. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: (964) 7503086122. Accepted 26 January, 2012 Existentialism is the movement in the nineteenth and twentieth century philosophy that addresses fundamental problems of human existence: death, anxiety, political, religious and sexual commitment, freedom and responsibility, the meaning of existence itself (Priest, 2001: 10). This study tries to define what existentialism is and stresses themes of existentialism. This research finally points out these themes of existentialism by studying on two existentialist drama plays written by Jean-Paul Sartre who was a prominent existentialist writer. The plays by Sartre studied in this research are ‘The Flies’ and ‘Dirty Hands’. Key words: Existentialism, freedom, absurdity, anguish, despair, nothingness. INTRODUCTION Existentialism is the philosophy that makes an religious, political, or sexual commitment? How should authentically human life possible in a meaningless and we face death? (Priest, 2001: 29). We can briefly define absurd world (Panza and Gale, 2008: 28). It is essentially existentialism as: ‘existentialism maintains that, in man, the search of the condition of man, the state of being and in man alone, existence precedes essence’. This free, and man's always using his freedom. Existentialism simply means that man first is, and only subsequently is, is to say that something exists, is to say that it is. -

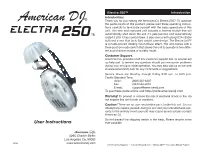

Electra 250.Pdf

Electra 250™ Introduction Introduction: ® Thank you for purchasing the American DJ Electra 250.™ To optimize American DJ the performance of this product, please read these operating instruc- tions carefully to familiarize yourself with the basic operations of this unit. This new and improved unit includes a thermal shutoff that will automatically shut down the unit if it gets too hot, and automatically restart it after it has cooled down. It also comes with a bright 24v/250w bulb and a new high tech, light weight case design. The Electra 250™ is a multi-colored rotating moon flower effect. The unit comes with a three position mode switch that allows the unit to operate in two differ- ent sound-active modes or a static mode. Customer Support: American DJ® provides a toll free customer support line, to provide set up help and to answer any question should you encounter problems during your set up or initial operation. You may also visit us on the web at www.americandj.com for any comments or suggestions. Service Hours are Monday through Friday 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Pacific Standard Time. Voice: (800) 322-6337 Fax: (323) 582-2610 E-mail: [email protected] To purchase parts online visit http://parts.americandj.com Warning! To prevent or reduce the risk of electrical shock or fire, do not expose this unit to rain or moisture. Caution! There are no user serviceable parts inside this unit. Do not attempt any repairs yourself, doing so will void your manufactures war- ranty. In the unlikely event your unit may require service please contact American DJ. -

Electra and Electra 60

Electra and Electra 60 These diagrams show you how to make the modular sculptures Electra, Electra 60, and, purely for the sake of completeness, the equivalent 24 and 12 module designs. Electra, or Electra 30, is probably my best known modular design. It dates from 1989 and was somewhat revolutionary at the time because of its use of a mixture of folding geometries. The name Electra is, of course, drawn from Greek mythology, but also references the similarity of the design to one of those, now somewhat outdated, pictures of electrons surrounding a nucleus in their shells. My first Electra was assembled from 30 modules which were folded using standard folding geometry. I soon discovered, however, that the angles of the design, and the strength of the assembly, could be improved by using mock platinum folding geometry to create the angle at which the pockets were set ( see pictures 10 and 12 ) . This change of angle not only improved the geometry but also allowed the tab of one module to extend very slightly around the corner inside the pocket of another ( see picture 22 ) , thus allowing them to hold together much more firmly, especially during the assembly phase. The original module now only survives in the 24-piece design, which cannot be made from the hybrid version, and also, unfortunately, in many unauthorised instructional videos on the internet. David Mitchell / Electra and Electra 60 1 In its original form, the Electra module will only make modular sculptures based on polyhedra which have four edges meeting at a vertex. However, it is a simple matter to hide one of the arms away inside the module to produce a three-armed version, or rather, two three-armed versions, one with two tabs and one pocket and the other with one tab and two pockets, which will go together to create sculptures based on polyhedra which have three edges meeting at a vertex. -

Greek Tragedy in Modern Greece

ALL IS WELL THAT ENDS TRAGICALLY: FILMING GREEK TRAGEDY IN MODERN GREECE ANASTASIA BAKOGIANNI The king’s a beggar now the play is done: All is well ended, if this suit be won, That you express content; which we will pay With strife to please you, day exceeding day. Ours be your patience, then, and yours our parts: Your gentle hands lend us, and take our hearts. William Shakespeare, All’s Well that Ends Well What does it take to adapt Greek tragedy successfully for the cinema?’ The debate centres on the issue of authenticity2 as well as the question of the successful integration of tragedy into the cinematic medium. The problematic nature of any attempt to adapt Greek tragedy for the cinema makes it a particularly challenging enterprise for filmmakers.3 In comparison with the cinematic reception of other aspects of ancient Greece and Rome, attempts to film Greek tragedy offer us fewer examples to work but they do attract the talents of some of the world’s best independent film directors,5 who have created some remarkable cincmatic receptions. ’ This is an exciting and ongoing debate and one articlc cannot hope to encompass all the issues concerned. The present article will focus on one aspect of this debate and is indebted to the pioneering work of Professor Marianne McDonnald and Dr Pantelis Michelakis in the field of the reception of Greek Drama on film. The author is also greatly indebted to Professor Mike Edwards and Professor Charles Chiasson for their many helpful suggestions. I am also indebted to Mr. -

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays*

A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays* The effects of recognition have to do with know- ledge and the means of acquiring it, with secrets, disguises, lapses of memory, clues, signs, and the like, and this no doubt explains the odd, almost asymmetrical positioning of anagnorisis in the domain of poetics… Structure and theme, poetics and interpretation, are curiously combined in this term… Terence Cave1 The fortuitous survival of three plays by each of the three tragic poets on the same story offers an unparalleled opportunity to consider some of the formal aspects of the genre, those which dictate the limits and possibilities of its dramatic enactment. Three salient elements constitute the irreducible minimum that characterizes the Orestes-Electra plot and is by necessity common to all three versions. These consist of nostos (return), anagnorisis (recognition) and mechanêma (the intrigue). This se- quence is known to us already from the Odyssey as the masterplot in the story of Odysseus himself and his return home, and it will come into play once again, nota- bly in Euripides’ version. Yet, at the same time, the Odyssey already contains the story of Orestes, who returns home to avenge his father, and it is this deed that pro- vides a contrapuntal line to the main story, which is that of the trials of Odysseus, his homecoming, his eventual vengeance on the suitors, and revelation of identity to friends and kin. The epic, however, gives only the bare facts of Orestes’ deed, which are recorded at the very outset in the proem (Od. -

Liz White Is an Actor Who Has Appeared in a Wide Variety of Roles on Stage and in Film and Television

Liz White is an actor who has appeared in a wide variety of roles on stage and in film and television. One of her most recent film roles was in Pride (2014) directed by Marcus Warchus. Among her other film roles, Liz has played Pamela in Vera Drake (2004) directed by Mike Leigh, and she starred as the eponymous woman in the 2012 film version of The Woman in Black, based on the novel by Susan Hill. For BBC Television, Liz played WPC/WDC Annie Cartwright in Life on Mars (2006/7), Caroline in the adaptation of The Crimson Petal and the White (2011), and Lizzie Mottershead in the series Our Zoo (2014). Other television roles have been Eileen in Teachers (2003), Jess Mercer in The Fixer (2008), and Lucille in The Paradise (2013). Liz’s stage credits have included three acclaimed performances at the National Theatre. She played Heavenly Critchfield in Laurie Sansom’s production of Spring Storm by Tennessee Williams, which transferred from the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, to the Cottesloe (2010), Anne Frankford in A Woman Killed With Kindness by Thomas Heywood, directed by Katie Mitchell in the Lyttelton (2010), and double roles in Marianne Elliot’s revival of Port by Simon Stephens in the Lyttelton (2013). In Autumn, 2014, Liz played the role of Chrysothemis in Ian Rickson’s production of Sophocles’ Electra at the Old Vic Theatre. The production used the version of the play written by Frank McGuinness and starred Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra. In this interview, recorded by Chrissy Combes at the Old Vic Theatre on Thursday 11 December 2014, Liz talked about the experience of playing Chrysothemis, Electra’s sister.