PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Op Zoek Naar De Canon. Criteria Ter Selectie Van Een Moderne Schrijversbiografie in Vlaanderen: Enkele Praktische En Theoretische Reflecties

Op zoek naar de canon. Criteria ter selectie van een moderne schrijversbiografie in Vlaanderen: enkele praktische en theoretische reflecties door Stefan VAN DEN BOSSCHE Abstract In Flanders chere has been si nee approximacely 1990 a cercain rise of li terary biographies. Ic has generally been accepced chat the ideal biography is a quescion of finding the right dialogue becween licerature and science, and chat the value of the biography is decermined, in good as well as in bad ways, by the talent of the biographer. Recent research on the licerary canon was especially focused on the personal publications, the group-participation, pos sible side-activicies in licerary regions and the positive recepcion of the work of the subject. Nevercheless a large number of less-important wricers has influenced the percepcion of the literal history. The contemporary licerary canon is only of secondary importance to decerminate the choice of the bio grapher. Especially admiracion, identificacion and the will of rehabilicacion stimulace him to write down a certain live-story. Toen Jan te Winkel in 1892 zijn an1bt aan de Amsterdamse universiteit aanvaardde, zag hij het als de voornaamste opdracht van de toekomstige onderzoekers van de Nederlandse letterkunde dat zij de literatuur van een bepaalde periode in verband zouden kunnen brengen met de maat schappelijke omstandigheden waarin zij kon ontstaan en gedijen. En vooral: De geschiedvorscher onzer letterkunde evenwel moet zijne taak veel zijdiger opvatten. Hij moet kunnen aantonen, wat er algemeens, maar ook wat er persoonlijk eigenaardigs is in de gewrochten der liccerarische kunst. Daartoe moet hij aanleg en karakter, werkkracht en werklust der schrijvers onderzoeken en erachten te verklaren uit hunne afkomst, opvoeding en levenservaringen, uit hunne persoonlijkheid, zoals die was en werd. -

Onze-Lieve-Vrouw Van Vlaanderen

v 1-1 /2-2008 VAN MENSEN EN DINGEN 41 Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Vlaanderen Guido Vloemans - Kris Lauwers Een haast onbekend beeld en een overbekend lied: het prachtige beeld van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Vlaanderen en het lied 'Liefdegaf U dui zend namen'. Hoe is de band tussen beiden ontstaan en weer losge raakt? Over dit en nog veel meer gaat dit artikel. Het onbekende beeld Voorgeschiedenis: Kerk en Beeld In de Posteernestraat te Gent, precies op de plaats waar Lodewijk van Male, graaf van Vlaanderen, een kasteel bezat, waarin later Filips de Goede, de eigenlijke stichter van de Nederlanden, heeft gewoond, kopen de paters jezuïeten in 1833 de gebouwen en de kapel van de oude abdij Oost-Eeklo. Als de kapel te klein wordt, laten de paters in mei 1842 een kerk bouwen. Deze wordt op 13 januari 1844 door Mgr. Delebecque, bisschop van Gent, geconsacreerd. Zij wordt toegewijd aan "Maria-Ten hemelopgenomen" en de heiligen Ignatius en Xaverius. Reeds heel vlug ontstaat er een grote lekenbeweging: de Aartsbroederschap van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter bekering van de zon- VAN MENSEN EN DINGEN Vl-1/2-2008 42 50 jaar viering (1) Uit J.M. Bergmans s.j.: Vijftig jarig Jubelfeest der Plechtige Kroning van het beeld van Onze Lieve Vrouw. Gent, Drukkerij A. Huyschauwer en L. Scheerder, s.d., 32 blz.; blz. 11-13. (2) J.B. De Cuyper (1807- 1852) was Ij ' samen met zijn broer Pieter-Joseph 1 een gekende beeldhouwer. In "Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis" ver scheen in 1930 een speciale druk · van een artikel door EM. -

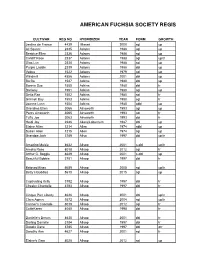

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

1041 Katalog.Pdf

PB 1 WWW.PHAEDRACD.COM · 1992 - 2012 Phaedra’s Whys and Wherefores !is catalog simultaneously lists and celebrates the achievements of Phaedra in the twenty years of its existence. At "rst blush publishing just over one hundred CDs in twenty years time may not look impressive. But it is very impressive, as you will see once you know the whys and wherefores of Phaedra. It is the purpose of this introduction to tell you about them. In spite of the .com extension in the URL of its website (www.phaedracd.com), Phaedra is not a commercial undertaking. It is part of a non-pro"t organization, Klassieke Concerten vzw. It was started by one man, and it still is almost entirely the work of one man. He has no sta#, not even a part-time secretary. His o$ce is a room in his house; his storage space, another room. He does everything himself. He decides which music Phaedra will publish, often searching out totally unknown works, including quite a few that are available only as manuscripts. He chooses the performers, in consultation with the composers if these are still alive. He takes care of the logistics of the recording sessions, and of the production process, of the covers and booklets as well as of the CDs proper. He is in charge of all publicity and of marketing Phaedra. It is impossible to justly evaluate the achievements of Phaedra without knowing it is a one-man operation. Like most Flemish non-pro"t organizations, it is also a shoestring operation. -

Twentieth-Century Flemish Art Song: a Compendium for Singers. (Volumes I and II)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1994 Twentieth-Century Flemish Art Song: A Compendium for Singers. (Volumes I and II). Paul Arthur Huybrechts Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Huybrechts, Paul Arthur, "Twentieth-Century Flemish Art Song: A Compendium for Singers. (Volumes I and II)." (1994). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5729. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5729 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

PDF Van Tekst

Vlaamsche Arbeid. Jaargang 23 [18] bron Vlaamsche Arbeid. Jaargang 23 [18]. Standaard Boekhandel, Brussel 1928 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_vla011192801_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. VII [Nummer 1/2] Inhoud I. - Bijdragen ALBERT K.: Evolutie en Revolutie 102 BERGHEN R.: De dood van Ferd. 225 Christly BRUNCLAIR V.J.: In memoriam Paul 139 Van Ostayen - Pelgrims in Avondland 294 - Pantalonnade 329 - Heil de Natte Vingerling 330 - Dorpsdans 330 BURSSENS G.: Ver verschiet 22 - Inkeer 23 - Laatste Zonsonderdgang 164 - De Mieren 292 - De Stroom 293 CELEN Dr V.: Achtiendeeuwsche 307 Gruwelspelen DAMBRE Dr O.: Psychologie van den 79 tachtiger - Otta Karrer 82 - Waardeering van Woordkunst 262 ELIAS Dr H.J.: Geschiedenis van 96 Zwitserland FRANCKEN F.: P. v. Ostayen voor en 165 na den oorlog GRAULS A.W.: Paul van Ostayen 173 GUIETTE Dr Rob.: De Roman-kunst 349 HALLEN Dr van der: Tony Bergmann 30 HOLDER Jan van: Zomernacht 29 INDESTEGE Dr L.: Het dramatisch en 209 biographisch werk van H. Roland-Holst Vlaamsche Arbeid. Jaargang 23 [18] - De werken der laatste jaren 331 JOOSTENS P.: P. v. Ostayen herdacht 168 LEONARD Ed.: Bouwkunst 104 LIGETI P.: Het nieuw Pantheon 3 MARSMAN H.: De criticus Paul van 174 Oostayen MOENS W.: De dichter P. v. Ostayen en 175 de Studenten der Gentse Universiteit MULS J.: Jacob Smits 92 - Paul van Ostayen en de Stad 129 OSTAYEN P. van: Vier Proza's 42 - Het Dorp 47 - Nagelaten Gedichten 182 - Self-Defense 188 - Diergaarde voor Kinderen van nu 289 Vlaamsche Arbeid. -

![Jaarverslag 1963 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2212/jaarverslag-1963-pdf-7062212.webp)

Jaarverslag 1963 [PDF]

BELGISCHE RADIO E N TELEVISIE INSTITUUT DER NEDERIHNDSE UITZENDINGEN JAAROVERZICHT 1 9 6 3 BELGISCHE RADIO EN TELEVISIE„ Instituut der Nederlandse Uitzendingen „ JAAROVERZICHT 1963 I. TEN GELEIDE » Het beleid bij radio en televisie werd voor 1963 gekenmerkt door een drietal gemeen schappelijke punten. Ze hebben betrekking op de geldmiddelen, de menselijke hulpmiddelen en de actualiteitenrubrieken. Voor 1963 bedroeg het aandeel van het Instituut der Nederlandse Uitzendingen in de overheidstoelage nagenoeg tachtig miljoen meer dan het jaar voordien, toen het merkelijk beneden de 300 miljoen-grens bleef (28O.725.OOO). Deze kredietverruiming heeft tot een merkelijke kwaliteitsverbetering geleid. Jammer genoeg konden deze bijkomende miljoenen niet worden besteed om in een dringende behoefte te voorzien, t.w, de volledige bezetting van de nieuwsdiensten. Wegens de hoge eisen die bij de aanwerving van journalisten moeten gesteld wor den, bleef het aantal geslaagde kandidaten ver beneden het aantal te begeven betrekkingen. Dit tekort aan medewerkers vormt dan weer een geluk kige tegenstelling met de overvloedige nieuws voorziening rond gebeurtenissen die door de ge hele wereld intens werden meegeleefd. Door een verslaggeving met vaak dramatische accenten over de moordaanslag op president Kennedy, de dood strijd van paus Johannes en de verkiezing van zijn opvolger, alsook over het Tweede Vaticaans Concilie, verkregen de beide media een waarlijk universele dimensie. * Wat meer in het bijzonder de radio betreft, mag worden gewezen op een aantal be langrijke initiatieven die zowel op de program ma's als op de technische uitrusting betrekking hebben. Dank zij een vernieuwing van de instal latie kunnen de hoorspelen thans in veel gun stiger voorwaarden worden opgenomen, hetgeen op een gelukkige wijze tegemoet komt aan het streven om van het luisterspel een volwaardig artistiek genre te maken. -

Biography Institute Jaarverslag Instuut 2020 Biografie

Biography Institute Jaarverslag Biografie Instuut 2020 Jaarverslag Postal address Biography Institute Annual report 2020 Faculty of Arts P.O. Box 716 NL-9700 AS Groningen Visiting address Oude Boteringestraat 32 9712 GJ Groningen Telephone +31 (0) 50 363 5816/9069 www.biografieinstituut.nl www.rug.nl/biografieinstituut [email protected] Annual Report Biography Institute University of Groningen, The Netherlands 2020 GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY PRESS GUP Bataviaasch nieuwsblad Nov 1, 1905 Preface 6 Biography Institute 1.1 Employees 7 1.2 PhD positions 7 1.3 Finance 8 1.4 Funding 8 1.5 Website and Newsletter 8 1.7 Biography Studies 9 Projects 2.1 Biography projects 11 2.2 Completed projects 20 2.3 Digitization projects 33 2.4 Publications 34 Scientific publications 34 Professional publications 35 Lectures and scientific activities 37 Education and partnerships 3.1 Education 42 3.2 Dutch Biography Portal 42 3.3 Frisian Biography Institute 42 Preface Since its foundation in 2004 the objective of the Biography Institute is two- fold. On the one hand, it offers an infrastructure and substantive support to academics who are engaged in a biographical research. On the other, it stimulates and develops the theoretical foundation of biography as a scientific genre. With the establishment of a chair in biography on 1 March 2017, followed by the foundation of the Department of History and Theory of Biography on 1 March 2012, the Biography Institute was allowed to carry out PhD projects. These projects were very popular: until now, 20 theses were completed, for the greatest part biographies. Until now, each of these biographies was published by a commercial publishing house. -

The Life of Alice Nahon (1896-1933)

SUMMARY Manu van der Aa, ‘Love is what I have loved’. The life of Alice Nahon (1896-1933). This study is a biography of the once famous and bestselling Flemish poet Alice Nahon (1896-1933). Her rise to fame began shortly after the publication of her first volume of poems, Vondelingskens, in 1920. At the same time she was mythologized, by her entourage (first and foremost by her father, who was also her publisher). Nahon herself – although sometimes a bit reluctantly – also contributed to her own myth, which depicted her as a sickly, melancholy, half-saintly young woman who wrote simple, touching and sincere poetry. However, that she was not a ‘saint’, as her entourage would have us believe, became apparent following the publications of, among others, Eric Defoort (1991) and Ria van den Brandt (1996). Nonetheless it was clear that more and thorough research was needed to straighten out some facts. Based on such research, this book shows that Alice Nahon was far from a saintTWEE MAAL DIT WOORD DICHT BIJ ELKAAR. She was a woman, who after having needlessly spent more than seven years in sanatoriums, grabbed her freedom and went in search of happiness. The story of her life is one of literary success and financial distress, of numerous love affairs and permanent health problems, of living to the full and dying young. Alice Nahon met and knew quite a few important artists of her time, such as Michel Seuphor, Eddy du Perron and Gerard Walschap. She was also very close with a lot of influential people of the pro-Flemish Movement, part of which converted to the extremist right in the mid-1930’s, turning Nahon into a ‘flamingant’ iconSTAAT DEZE TERM EN TOELICHTING OOK IN DE BOEK HIERVOOR. -

Colofon in Dit Nummer

_ g_ g Colofon In dit nummer Historica is een uitgave van de Vereniging voor Vrouwen- / Oral history / / Genderview / geschiedenis en verschijnt drie keer per jaar (februari, juni en oktober). 3 Oral history met video en de tweede 24 Els Flour Informatie op internet: www.gendergeschiedenis.nl feministische golf Sophie Bollen Redactie Josien Pieterse en Grietje Keller Greetje Bijl (public relations) / Recensie / Sophie Bollen (hoofdredactie) / Nederlands-Indië / Barbara Bulckaert (eindredactie) 27 Vriendschap en troost in de vrienden- Inge-Marlies Sanders (penningen) 6 Nederlandse koloniale vrouwen en rol van Petronella Moens Hilde Timmerman rassenbewustzijn in Nederlands-Indië Sara Tilstra (eindredactie) Barbara Bulckaert Karin Hietkamp Redactieadres / Onder de loep / Sophie Bollen / Literatuur / VUB/Vakgroep Metajuridica 28 Interviews met moffenmeiden Pleinlaan 2 12 Het onbekende levensverhaal 1050 Brussel / Recensie / E-mail: [email protected] van de bekende Antwerpse dichteres Tel. 02-6291495 Alice Nahon 30 Nieuwe perspectieven op het Manu van der Aa verzamelen, bewaren en delen van Lidmaatschap VVG, p/a IIAV, Obiplein 4, 1094 RB Amsterdam vrouwengeschiedenis Tel: 020-6651318; Fax: 020-6655812, / Textielgeschiedenis / Els Flour Internet: www.gendergeschiedenis.nl. Voor privé-personen bedraagt de contributie €27,50 per 15 Een geschiedenis van ondergoed 31 / Service en nieuwe boeken / jaar (lidmaatschap); reductie-lidmaatschap (voor studen- Chantal Bisschop ten of mensen met een inkomen onder €700,- p.m.: €22,- per jaar (studentlid, ovv collegekaartnummer). Leden van de VVG ontvangen Historica automatisch en hebben stem- / Nederlands-Indië / recht bij de jaarlijkse Algemene Ledenvergadering. 18 Vergeten vrouwenstemmen uit de Voor instellingen kost een abonnement op Historica €22,-. Abonnees kunnen geen aanspraak maken op de rechten negentiende-eeuwse Indisch- van de leden. -

Biography Institute Annual Report Biography Instute 2019 Annual Report Biography

Biography Institute Annual Report BiographyAnnual Report Instute 2019 Postal address Biography Institute Faculty of Arts P.O. Box 716 NL-9700 AS Groningen Visiting address Oude Boteringestraat 32 9712 GJ Groningen Telephone +31 (0) 50 363 5816/9069 www.biografieinstituut.nl www.rug.nl/biografieinstituut Annual Report 2019 [email protected] Annual Report Biography Institute University of Groningen, The Netherlands 2019 GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY PRESS GUP Preface 6 Biography Institute 1.1 Employees 7 1.2 PhD positions 7 1.3 Finance 8 1.4 Funding 8 1.5 Website and Newsletter 8 1.7 Biography Studies 9 Projects 2.1 Biography projects 11 2.2 Completed projects 20 2.3 Digitization projects 33 2.4 Publications 34 Scientific publications 34 Professional publications 35 Lectures and scientific activities 37 Education and partnerships 3.1 Education 42 3.2 Dutch Biography Portal 42 3.3 Frisian Biography Institute 42 Preface Since its foundation in 2004 the objective of the Biography Institute is two- fold. On the one hand, it offers an infrastructure and substantive support to academics who are engaged in a biographical research. On the other, it stimulates and develops the theoretical foundation of biography as a scientific genre. With the establishment of a chair in biography on 1 March 2017, followed by the foundation of the Department of History and Theory of Biography on 1 March 2012, the Biography Institute was allowed to carry out PhD projects. These projects were very popular: until now, 20 theses were completed, for the greatest part biographies. Until now, each of these biographies was published by a commercial publishing house. -

Download Als

FILIP DE PILLECYN STUDIES XII ( 2016 ) Filip De Pillecyn Studies Jaarboek van het Filip De Pillecyncomité Redactie Emmanuel Waegemans Jurgen De Pillecyn Etienne Van Neygen Redactieraad Prof. dr. Dirk De Geest Prof. dr. Frans-Jos Verdoodt Redactieadres Filip De Pillecyn Studies Hoofdredacteur Prof. dr. E. Waegemans Ballaarstraat 106 2018 Antwerpen (03) 237 80 10 [email protected] ISBN 978 90 81796 98 9 D : 2016 / 20.624 / 1 Druk : EPO vzw www.epo.be Verantwoordelijke uitgever : Filip De Pillecyncomité, Ballaarstraat 106, 2018 Antwerpen Een nummer van Filip De Pillecyn Studies kost 25 €, abonnees zijn meteen ook lid van het FDP Comité en genieten van gratis toegang tot activiteiten. Een nummer/lidmaatschap kan besteld worden door storting op rekening 850 – 8108291 – 59 (IBAN : BE 84 8508 1082 9159 / BIC : SPAABE22) van het Filip De Pillecyncomité. Zie onze website : www.fi lipdepillecyn.be Inhoud Studies – Patrick Auwelaert. Geïllustreerde en bibliofi ele boekuitgaven van Filip De Pillecyn (3) : Riet Verhelst en Blauwbaard 7 – Jurgen De Pillecyn. Karel De Stoute, luisterspel door Filip De Pillecyn en Arthur Meulemans (1940) 31 – Jan Verstraete. Filip De Pillecyn voor de krijgsraad 49 – Etienne Van Neygen. De Pallieter-koppen : spiegels van een volledige persoonlijkheid 85 Extra muros – Dirk Rochtus. Bij de presentatie van de FDP Studies XI, Beveren, 8 november 2015 205 Nieuw – De aanwezigheid in het Frans 213 Recensie – Paul Servaes. Filip De Pillecyn in nieuwe bloemlezing 233 Kroniek 2015 237 Personalia 241 Studies Geïllustreerde en bibliofi ele boekuitgaven van Filip De Pillecyn (3) : Riet Verhelst en Blauwbaard patrick auwelaert Veel boekuitgaven van Filip De Pillecyn hebben een geïllustreerde omslag en/of bevatten illustraties binnenin.