Utah Women's Walk Oral Histories Directed by Michele Welch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

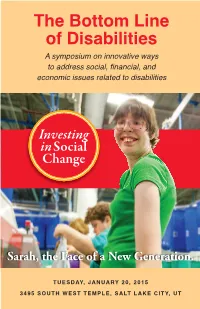

The Bottom Line of Disabilities 2015

The Bottom Line of Disabilities A symposium on innovative ways to address social, financial, and economic issues related to disabilities Inesting in Social Change Sarah, the Face of a New Generation. TUESDAY, JANUARY 20, 2015 3495 SOUTH WEST TEMPLE, SALT LAKE CITY, UT EVENT PARTNERS Columbus Community Center (www.columbusserves.org) is recognized locally and nationally as a well-established, innovative nonprofit agency. Columbus works strategically with many stakehold - ers to support individuals with disabilities so they can make informed decisions and live with in - dependence in the community. After nearly five decades of serving thousands of individuals, Columbus is still finding innovative ways to provide individuals with disabilities the support to live with independence and dignity in our community. The Global Interdependence Center (www.interdependence.org) is a neutral convener of dialogue, organizing conferences and roundtable discussions around the country and around the world to identify and address important global issues. Its programming promotes global partnerships among government officials, financial institutions, businesses leaders, and academic researchers. EVENT SPONSORS AGENDA EVENT EMCEES 8:30 A.M. TO 9:30 A.M. Michael Drury, McVean Trading The Policies that Shape Opportunity, & Investments Controversy, and Change Stephanie Mackay, Columbus Public policy and traditional funding sources have created safety nets, pro - vided opportunity for community inte - gration, and given a voice to some of the most vulnerable in our communi - ties. There have been significant social changes as well as some unintended 7:30 A.M. TO 8 A.M. consequences. Registration & Continental Breakfast MODERATOR: Palmer DePaulis, Former 8:00 A.M. TO 8:30 A.M. -

State of West Virginia Office of the Attorney General Patrick Morrisey

State of West Virginia Office of the Attorney General Patrick Morrisey (304) 558-2021 Attorney General Fax (304) 558-0140 August 1, 2016 The Honorable Regina A. McCarthy Administrator U.S. Environment Protection Agency 1200 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, DC 20460 Submitted electronically via Regulations.gov Re: Request for extension of time to comment on the proposed rule, Clean Energy Incentive Program Design Details, 81 Fed. Reg. 42,940 (June 30, 2016), docket no. EPA-HQ-OAR-2016-0033, by the undersigned States and state agencies Dear Administrator McCarthy: As the chief legal officers and officials of the States and state agencies that obtained the stay of the "Clean Power Plan" from the United States Supreme Court, we urge you to immediately extend the comment period on the proposed rule titled, Clean Energy Incentive Program Design Details, 81 Fed. Reg. 42,940 (June 30, 2016) (the "CEIP"). The comment period should be extended for at least sixty days following the termination of the Power Plan stay. Of course, if the Power Plan does not survive judicial review, the CEIP should then simply be withdrawn. Several reasons support this extension request. First, extending the comment deadline is required by the stay. Under established precedent, the stay order "halt[s] or postpone[s]" the Power Plan, including "by temporarily divesting [the Power Plan] of enforceability." Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 428 (2009). In other words, the stay "suspend[s] the source of authority to act" by "hold[ing] [the Rule] in abeyance." Id. As the -

Owens Says He's Prepared to Fill Shoes of Matheson

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU The Utah Statesman Students 5-18-1984 The Utah Statesman, May 18, 1984 Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/newspapers Recommended Citation Utah State University, "The Utah Statesman, May 18, 1984" (1984). The Utah Statesman. 1544. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/newspapers/1544 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Students at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Utah Statesman by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Owens says he's prepared to fill shoes of Matheson Editor'snote: Wayne Owens and tion, flooding, social service, public KemGardner, candidates for gover buildings in decay. All those focus nor, were on campus Tuesday for the around income problems." monthlymeeting of the Board of Owens, a former U.S. con R,gents. gressman, said the main ByTAMARA THOMAS "non-gov erning" responsibility of staffwriter Utah's top office is to attract groups and find avenues that will provide Democratic gubernatorial candidate more revenue to the state. WayneOwens said he is pleased with "The other aspect of being gover the job that retiring Utah Gov. Scott nor is to provide leadership ," he said. Mathesonhas done. Included in the governor's mode of Andnow he said he is ready to leadership , according to Owens, is stop in and take up where Matheson "to provide input into the cultural op willleave off. portunities of the state." "The solutions are really just get tingunderway ," Owens said. "Scott Q\..venssaid he is currently making has been a great governor." a strong showing in the gubernatorial A practicing Salt Lake City at race, in which five Republicans and torney who has been working for the two other Democrats are Vying for plaintiffsin the Southern Utah the office. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

The Long Red Thread How Democratic Dominance Gave Way to Republican Advantage in Us House of Representatives Elections, 1964

THE LONG RED THREAD HOW DEMOCRATIC DOMINANCE GAVE WAY TO REPUBLICAN ADVANTAGE IN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTIONS, 1964-2018 by Kyle Kondik A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Baltimore, Maryland September 2019 © 2019 Kyle Kondik All Rights Reserved Abstract This history of U.S. House elections from 1964-2018 examines how Democratic dominance in the House prior to 1994 gave way to a Republican advantage in the years following the GOP takeover. Nationalization, partisan realignment, and the reapportionment and redistricting of House seats all contributed to a House where Republicans do not necessarily always dominate, but in which they have had an edge more often than not. This work explores each House election cycle in the time period covered and also surveys academic and journalistic literature to identify key trends and takeaways from more than a half-century of U.S. House election results in the one person, one vote era. Advisor: Dorothea Wolfson Readers: Douglas Harris, Matt Laslo ii Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………....ii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………..v Introduction: From Dark Blue to Light Red………………………………………………1 Data, Definitions, and Methodology………………………………………………………9 Chapter One: The Partisan Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution in the United States House of Representatives, 1964-1974…………………………...…12 Chapter 2: The Roots of the Republican Revolution: -

Newsletter02.Pdf

Fall 2002 sion at the University. A committee has Now I am sounding like a politician get- From the Director been formed. Could the Institute become ting ready to run for re-election. But I am a center for policy work? Should it seek so proud of what we have done, and of the expansion? How about new programs? great work of our staff, that I just want to These are just some of the questions the crow a little. Please excuse me. And I am committee will explore. After thirty-seven not running again! years of excellence, “If it ain’t broke, don’t I still need to work. I’m looking for fix it,” must apply. But it is also timely to some consulting opportunities. I would look to the future. like to hang out here through some teach- I often contemplate the wonderful char- ing. I will aid the new director as coal sketch of our founder Robert H. requested. The Hinckley Institute of Hinckley by Alvin Gittins that warms my Politics and the University of Utah will office. The eyes focus on the future. The remain a big part of my life. face is filled with compassion yet reflects a But there are mountains to climb- no-non-sense attitude. Par-ti-ci-pa-tion - as motorcycles to rev-grandchildren to hug- Mr. Hinckley said it while emphasizing and “many a mile before I sleep.” every syllable - is what we are about. And participation is what my staff and I have sought to deliver. I will miss my second family. -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Inpatient Services Hospitals

Hospitals – Inpatient Services You may get your inpatient care at any Utah hospital that accepts Medicaid. All outpatient hospital care MUST be at one of the Healthy U network hospitals listed in the "Outpatient" section below. Hospitals – Outpatient/Emergency Room Services American Fork Mount Pleasant American Fork Hospital Sanpete Valley Hospital 170 North 1100 East….........................(801) 855-3300 1100 South Medical Drive ...................(435) 462-2441 Bountiful Murray Lakeview Hospital Intermountain Medical Center 630 East Medical Drive .......................(801) 292-6231 5121 South Cottonwood Street ...........(801) 507-7000 Brigham City The Orthopedic Specialty Hospital (TOSH) Brigham City Community Hospital 5848 Fashion Boulevard......................(801) 314-4100 950 Medical Drive .............................. (435) 734-9471 Ogden Cedar City McKay-Dee Hospital Valley View Medical Center 4401 Harrison Boulevard ....................(801) 627-2800 1303 North Main Street .......................(435) 868-5000 Ogden Regional Medical Center Delta 5475 South 500 East ...........................(801) 479-2111 Delta Community Medical Center 128 White Sage Avenue .....................(435) 864-5591 Orem Orem Community Hospital Draper 331 North 400 West ............................(801) 224-4080 Timpanogos Regional Hospital Lone Peak Hospital 750 West 800 North ............................(801) 714-6000 11800 South State Street ...................(801) 545-8000 Fillmore Park City Park City Medical Center Fillmore Community Medical -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2002 Library of Congress Photo Credits Independence Avenue, SE Photographs by Anne Day (cover), Washington, DC Michael Dersin (pages xii, , , , , and ), and the Architect of the For the Library of Congress Capitol (inside front cover, page , on the World Wide Web, visit and inside back cover). <www.loc.gov>. Photo Images The annual report is published through Cover: Marble mosaic of Minerva of the Publishing Office, Peace, stairway of Visitors Gallery, Library Services, Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building. Washington, DC -, Inside front cover: Stucco relief In tenebris and the Public Affairs Office, lux (In darkness light) by Edward J. Office of the Librarian, Library of Congress, Holslag, dome of the Librarian’s office, Washington, DC -. Thomas Jefferson Building. Telephone () - (Publishing) Page xii: Library of Congress or () - (Public Affairs). Commemorative Arch, Great Hall. Page : Lamp and balustrade, main entrance, Thomas Jefferson Building. Managing Editor: Audrey Fischer Page : The figure of Neptune dominates the fountain in front of main entrance, Thomas Jefferson Building. Copyediting: Publications Professionals Page : Great Hall entrance, Thomas Indexer: Victoria Agee, Agee Indexing Jefferson Building. Production Manager: Gloria Baskerville-Holmes Page : Dome of Main Reading Room; Assistant Production Manager: Clarke Allen murals by Edwin Blashfield. Page : Capitol dome from northwest Library of Congress pavilion, Thomas Jefferson Building; Catalog Card Number - mural “Literature” by William de - Leftwich Dodge. Key title: Annual Report of the Librarian Page : First floor corridor, Thomas of Congress Jefferson Building. Inside back cover: Stucco relief Liber delectatio animae (Books, the delight of the soul) by Edward J. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 159 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 8, 2013 No. 64 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces Wednesday, April 24, 2013, the House called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House his approval thereof. stands in recess subject to the call of pore (Mr. MEADOWS). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- the Chair. f nal stands approved. Accordingly, (at 9 o’clock and 4 min- f utes a.m.), the House stood in recess DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER subject to the call of the Chair. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE PRO TEMPORE f The SPEAKER pro tempore. The The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- b 1022 fore the House the following commu- Chair will lead the House in the Pledge nication from the Speaker: of Allegiance. JOINT MEETING TO HEAR AN AD- The SPEAKER pro tempore led the DRESS BY HER EXCELLENCY WASHINGTON, DC, Pledge of Allegiance as follows: May 8, 2013. PARK GEUN-HYE, PRESIDENT OF I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the I hereby appoint the Honorable MARK R. THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA United States of America, and to the Repub- MEADOWS to act as Speaker pro tempore on During the recess, the House was this day. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. called to order by the Speaker at 10 JOHN A. -

Downtown Salt Lake City We’Re Not Your Mall

DOWNTOWN SALT LAKE CITY WE’RE NOT YOUR MALL. WE’RE YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD. What if you took the richest elements of an eclectic, growing city and distilled them into one space? At The Gateway, we’re doing exactly that: taking a big city’s vital downtown location and elevating it, by filling it with the things that resonate most with the people who live, work, and play in our neighborhood. SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH STATE FOR BUSINESS STATE FOR STATE FOR #1 - WALL STREET JOURNAL, 2016 #1 BUSINESS & CAREERS #1 FUTURE LIVABILITY - FORBES, 2016 - GALLUP WELLBEING 2016 BEST CITIES FOR CITY FOR PROECTED ANNUAL #1 OB CREATION #1 OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES #1 OB GROWTH - GALLUP WELL-BEING 2014 - OUTSIDE MAGAZINE, 2016 - HIS GLOBAL INSIGHTS, 2016 LOWEST CRIME IN NATION FOR STATE FOR ECONOMIC #6 RATE IN U.S. #2 BUSINESS GROWTH #1 OUTLOOK RANKINGS - FBI, 2016 - PEW, 2016 - CNBC, 2016 2017 TOP TEN BEST CITIES FOR MILLENNIALS - WALLETHUB, 2017 2017 DOWNTOWN SALT LAKE CITY TRADE AREA .25 .5 .75 mile radius mile radius mile radius POPULATION 2017 POPULATION 1,578 4,674 8,308 MILLENNIALS 34.32% 31.95% 31.23% (18-34) EDUCATION BACHELOR'S DEGREE OR 36.75% 33.69% 37.85% HIGHER HOUSING & INCOME 2017 TOTAL HOUSING 1,133 2,211 3,947 UNITS AVERAGE VALUE $306,250 $300,947 $281,705 OF HOMES AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD $60,939 60,650 57,728 INCOME WORKFORCE TOTAL EMPLOYEES 5,868 14,561 36,721 SOURCES: ESRI AND NEILSON ART. ENTERTAINMENT. CULTURE. The Gateway is home to several unique entertainment destinations, including Wiseguys Comedy Club, The Depot Venue, Larry H.