The Long Red Thread How Democratic Dominance Gave Way to Republican Advantage in Us House of Representatives Elections, 1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 8, folder “Congress - Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. r Digitized from Box 8 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Presi dent's Mail - May 11, 1976 House 1. Augustus Hawkins Writes irr regard to his continuing · terest in meeting with the President to discuss the· tuation at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission prior to the appoint ment of a successor to Chairman owell W. Perry. 2. Larry Pressler Says he will vote to sustain e veto of the foreign military assistance se he believes the $3.2 billion should be u ed for nior citizens here at horne. 3. Gus Yatron Writes on behalf of Mrs. adys S. Margolis concerning the plight of Mr. Mi ail ozanevich and his family in the Soviet Union. 4. Guy Vander Jagt Endorses request of the TARs to meet with the President during their convention in June. -

Hearing Committee on Veterans' Affairs House of Representatives

THE NEED TO DEVELOP EDUCATION AND TRAINING PROGRAMS ON THE MEDICAL RESPONSES TO THE CONSEQUENCES OF TER- RORIST ACTIVITIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 14, 2001 Printed for the use of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs Serial No. 107–17 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 82–748PS WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, Chairman BOB STUMP, Arizona LANE EVANS, Illinois MICHAEL BILIRAKIS, Florida BOB FILNER, California TERRY EVERETT, Alabama LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana CORRINE BROWN, Florida JACK QUINN, New York JULIA CARSON, Indiana CLIFF STEARNS, Florida SILVESTRE REYES, Texas JERRY MORAN, Kansas VIC SNYDER, Arkansas HOWARD P. (BUCK) MCKEON, California CIRO D. RODRIGUEZ, Texas JIM GIBBONS, Nevada RONNIE SHOWS, Mississippi MICHAEL K. SIMPSON, Idaho SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada RICHARD H. BAKER, Louisiana BARON P. HILL, Indiana ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut TOM UDALL, New Mexico ANDER CRENSHAW, Florida HENRY E. BROWN, JR., South Carolina PATRICK E. RYAN, Chief Counsel and Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana, Chairman BOB STUMP, Arizona JULIA CARSON, Indiana MICHAEL BILIRAKIS, Florida BARON P. HILL, Indiana TERRY EVERETT, Alabama TOM UDALL, New Mexico (II) C O N T E N T S November 14, 2001 Page The Need to Develop Education and Training Programs on the Medical Re- sponses to the Consequences of Terrorist Activities ........................................ -

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

Gendered Complications of Covid-19: Towards a Feminist Recovery Plan

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship Fall 2021 Gendered Complications of Covid-19: Towards a Feminist Recovery Plan Linda C. McClain Boston University School of Law Naomi Cahn University of Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Linda C. McClain & Naomi Cahn, Gendered Complications of Covid-19: Towards a Feminist Recovery Plan, 22 Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law 1 (2021). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/978 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES GENDERED COMPLICATIONS OF COVID-19: TOWARDS A FEMINIST RECOVERY PLAN NAOMI R. CAHN* AND LINDA C. MCCLAIN** ABSTRACT COVID-19 exposed the limitations in the current economic system on public and private support for gender equity and the intersecting impact of gender, race, and class in that lack of support. Women of color, particularly those who are Black, Latina, or Native American, were at the intersection of the inequities in the pandemic economy. The catalogue of COVID-19's impact covers all aspects of women's lives: work, family, education, health, reproduction, mental and physical well-being, and leisure. This Article argues that COVID-19 has complex implications for gender equality and gender equity as state and local governments, the federal government, and pri- vate actors focus on recovery plans. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 152, Pt. 7 May 25, 2006 EXECUTIVE SESSION NAYS—30 Mr

9602 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 152, Pt. 7 May 25, 2006 EXECUTIVE SESSION NAYS—30 Mr. Kavanaugh was a deputy, with as Akaka Durbin Levin many as nine other such deputies on Baucus Feingold Menendez his level. Bayh Harkin Mikulski He was candid in some criticism of NOMINATION OF BRETT M. Bingaman Inouye Murray Boxer Jeffords Reed the handling of the matter; the public KAVANAUGH TO BE UNITED Cantwell Johnson Reid release of the report was not the choos- STATES CIRCUIT JUDGE FOR Clinton Kennedy Sarbanes ing of Independent Counsel. He testi- THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Dayton Kerry Schumer Dodd Lautenberg Stabenow fied that he believed that the Inde- CIRCUIT—Resumed Dorgan Leahy Wyden pendent Counsel statute ought to be The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under NOT VOTING—3 changed materially if it was to be re- the previous order, the Chair lays be- vised and that having Mr. Starr both Conrad Rockefeller Salazar fore the Senate the pending cloture on Whitewater and the impeachment of motion, which the clerk will state. The PRESIDING OFFICER. On this the President was too much. The legislative clerk read as follows: vote, the ayes are 67, the nays are 30. He wrote a law review article on the Three-fifths of the Senators duly cho- CLOTURE MOTION issue of peremptory challenges for sen and sworn having voted in the af- Black jurors and took the position that We the undersigned Senators, in accord- firmative, the motion is agreed to. ance with the provisions of rule XXII of the it was inappropriate, should not be Standing Rules of the Senate, do hereby The PRESIDING OFFICER. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E229 HON. JOE KNOLLENBERG HON. BOB STUMP HON. RONALD V. DELLUMS HON. CHARLES B. RA

February 12, 1997 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E229 pastime remained a white-only sport. On April REPEAL THE ESTATE TAX I would like to take this opportunity to high- 10, 1947, Jackie Robinson broke the color light one celebration that resonates personally. barrier in major league baseball, ending 71 HON. BOB STUMP This past Sunday, February 9, the Pullman years of exclusion for African-American ath- OF ARIZONA Blues Whistle Stop Tour departed Jack Lon- letes, when he was signed by Brooklyn Dodg- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES don Square in my hometown of Oakland, CA. er president Branch Rickey. Wednesday, February 12, 1997 This tour was created to coincide with a Feb- Jackie's path breaking career in professional ruary 16 celebration by the Historic Pullman baseball began on October 23, 1945, when he Mr. STUMP. Mr. Speaker, among the taxes Foundation in honor of the thousands of Afri- was signed to the Montreal Royals, the Dodg- the Internal Revenue Service collects, the es- can-American men and women who provided er's Triple-A farm team, as the first African- tate tax ranks as one of the most unfair. With the Pullman Co. and the railroads of America American player in the minor leagues. In his top rates reaching as high as 55 percent, the with over a century of faithful service on the first game, Jackie led the Royals to a 14±1 estate tax can and does force the sale of fam- passenger trains of railroad's Golden Age. victory over Jersey City Giants winning the re- ily businesses, farms, and ranches to satisfy My uncle, C.L. -

1 “Knock the EPA Out!” Environmental Politics and Community Identity In

“Knock the EPA Out!” Environmental Politics and Community Identity in Appalachian Ohio* In May 1988, millions of Americans tuned into a special edition of the Oprah Winfrey Show broadcast from a small town in southeastern Ohio, a region hard hit by industrial and mining losses. “They were middle class people, once earning good money in the coal mines [and] in the steel mills,” the show’s opening sequence declared as Rust Belt imagery flashed across the screen. “But the rug was pulled out from under them. They never imagined themselves standing in welfare lines, never imagined relying on food stamps.” As they discussed the problems of job losses in the area, many in the audience, especially those laid-off from the region’s mines, mills and power plants, blamed new environmental regulations, particularly the Clean Air Act, and envisioned a return to the industrial past. “The whole bottom line is: knock the EPA out!” railed one audience member. “We want work. We don’t want the clean air. We want the factories back. We want the mines back.”1 The late 1960s and early 1970s were a golden age for the communities of southeastern Ohio. Nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, local residents benefited from an upswing in mining employment prompted by the increased use of coal in electricity production. By the mid-1980s, however, a variety of factors including a lack of economic diversification, low education levels, and inadequate transportation as well as the increasing environmental standards encoded in the Clean Air Act manifested in high unemployment, poverty and out- migration. -

24, 1979 Tibie DA ?’ I WASHINGTON, D.C

LOC ATi Oh DA-i E \Mo.. Day, k r.1 THE WHITE HOUSE . WASHINGTON, D.C. T:biE DAY 5:30 a.m.THURSDAY Y!iOV[f I TIME 5;r .= ‘i ‘J0 AC-TWIT-Y 7I, z .A From I To 2 f The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 6:04 ! The President went to the Oval Office. 8:04 The President met to discuss legislative strategy on oil price decontrol with Senator Robert C. Byrd (D-West Virginia) 8:04 1 The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:04 9:06 1 The President participated in a breakfast meeting to discuss the economy and inflation with: Walter F. Mondale, Vice President W. Michael Blumenthal, Secretary of the Treasury Charles L. Schultze, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) I Alfred H. Kahn, Advisor and Chairman of the Council on Wage and Price Stability I James T. McIntyre, Jr., Director of the Office of I Management and Budget (OMB) Barry P. Bosworth, Director of the Council on Wage and Price Stability Stuart E. Eizenstat, Assistant for Domestic Affairs and Policy 9:06 1 I The President returned to the Oval Office. I I Ii 9:08 / 9:15 [ I The President met with his Assistant for National Security i I ! I Affairs, Zbigniew Brzezinski. I 9:30 /i 9:45 The President met to discuss the windfall profits tax on oil i I I I and the schedule of the House Committee on Ways and Means I with: 1i I Representative Al Ullman (D-Oregon) I Representative Dan Rostenkowski (D-Illinois) i I William H. -

Executive Summary of Report by Illinois Assembly on Political

ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE # ELECTORAL SYSTEMS E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y ILLINOIS ASSEMBLY ON POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND ALTERNATIVE #ELECTORAL SYSTEMS E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y S P R I N G 2 0 0 1 2 CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................ 7 Background .............................................................................................. 15 Participants, Illinois Assembly on Political Representation & Alternative Electoral Systems................................................................ 25 Appendix. A Comparison of Selected Electoral Systems .................. 29 Executive Summary, Report on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems I 3 4 FOREWORD In Spring 2000, the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois created the Illinois Task Force on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems. Governor Jim Edgar and Judge Abner Mikva served as co-chairs. The task force examined the effects of the change from cumulative to plurality voting in Illinois House elections, gathered information about alternative electoral systems that are used throughout the world, and considered how and how well those systems work in other regions of the country and world. With that information in hand, they brought together leaders from politics, the media, academe, business, and nonprofit organizations for the Illinois assembly on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems. The assembly met to explore the pros and cons of various electoral systems as they might be used in Illinois House elections. I am happy to present you with the final report of the Illinois Assembly. This report is very timely. Work on reapportionment and redistricting of local, state, and federal legislative districts has already begun. -

Political Science; *Polits; Secondary 7Ducation; Social Studies; Sociology; United States History 7PENTIF:7 PS *Irish Ami.Ricans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 129 690 SO 009 470 AUTHOF Krug, Mark M. -"TTL7 White Ethnic Groups and American Politics, Student Book. The Lavinia and Charles P. Schwartz Citizenship Project. INST7TUTI711 Chicago Univ., Ill. Graduate School of Education. 1DUB DATE 72 NOTE 99p.; For related documents, see SO 009 469-474 EDFS PF:CE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCFIPTOFS *Citizenship; Ethnic Grouping; *Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Ethnocentrism; Italian Americans; Jews; Polish Americans; Political Science; *Polits; Secondary 7ducation; Social Studies; Sociology; United States History 7PENTIF:7 PS *Irish Ami.ricans ABSIPACT This student book, one in a series of civic education materials, focuses on white ethnic groups and how they influence the operation of the American political system. The ethnicgroups which are investigated include Poles, Irish, Italians, and Jews. An ethnic person is defined as anyone who decides to identify with and live among those who share the same immigrant memories and values. Ethnic origin, ethnic loyalties, and ethnic considerations playan important role in the political process of the United States. A separate chapter focuses on each of the four minority groups and its role in the process of American politics. Jews, labeled as the shaken liberals, have historically been staunch supporters of the liberal tradition as a unified voter block, but apparent conservative trends are showing as a reaction to radical liberalism and its support of the Arab nations. The Irish built and dominated political organizations, known as machines, in several cities and their predominance in city politics continues today. Italians'were rather slow in getting into politics, but in general Italiansare politically conservative, strong American patriots, disunited due to internal identity conflicts, and assimilating rapidly into U.S. -

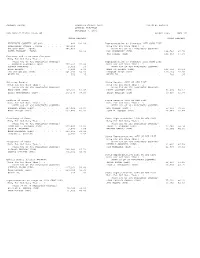

Results-Summary-Gen06 (PDF)

SUMMARY REPORT FRANKLIN COUNTY OHIO OFFICIAL RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 7, 2006 RUN DATE:11/29/06 08:45 AM REPORT-EL45 PAGE 001 VOTES PERCENT VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 842). 842 100.00 Representative to Congress 12TH CONG DIST REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 766,652 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 385,863 (WITH 367 OF 367 PRECINCTS COUNTED) VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 50.33 BOB SHAMANSKY (DEM) . 108,746 42.70 PAT TIBERI (REP) . 145,943 57.30 Governor and Lieutenant Governor (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Representative to Congress 15TH CONG DIST J. KENNETH BLACKWELL (REP). 122,601 32.80 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 ROBERT FITRAKIS . 3,703 .99 (WITH 434 OF 434 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BILL PEIRCE. 5,382 1.44 MARY JO KILROY (DEM). 109,659 49.58 TED STRICKLAND (DEM). 241,536 64.62 DEBORAH PRYCE (REP) . 110,714 50.06 WRITE-IN. 553 .15 WRITE-IN. 783 .35 Attorney General State Senator 03RD OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 316 OF 316 PRECINCTS COUNTED) MARC DANN (DEM) . 187,191 51.07 DAVID GOODMAN (REP) . 71,874 54.12 BETTY MONTGOMERY (REP) . 179,370 48.93 EMILY KREIDER (DEM) . 60,927 45.88 Auditor of State State Senator 15TH OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 251 OF 251 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BARBARA SYKES (DEM) .