CICIG in Guatemala: the Institutionalization of an Anti-Corruption Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guatemala República De Guatemala

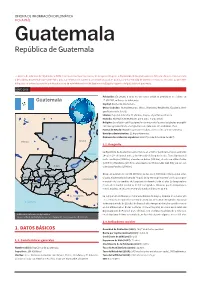

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Guatemala República de Guatemala La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios no oficiales. La presente ficha país no defiende posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. MAYO 2018 Población: En 20186 a falta de un censo oficial la población se estima en Guatemala 17.300.000, millones de habitantes. Capital: Ciudad de Guatemala. Otras ciudades: Quetzaltenango, Mixco, Vilanueva, Retalhuleu, Escuintla, Anti- gua Guatemala, Sololá. Idioma: Español (oficial) y 22 idiomas mayas, el garífuna y el xinca. Moneda: Quetzal (8,36 Quetzales por 1 Euro, marzo 2018). Religión: La religión católica sigue siendo mayoritaria pero las iglesias evangéli- cas han experimentado un importante crecimiento en los últimos años. Forma de Estado: República presidencialista, democrática y representativa. División administrativa: 22 departamentos. Número de residentes españoles: 10.287 (31 de diciembre de 2017) Flores MÉXICO BELICE 1.2. Geografía La República de Guatemala está situada en el Istmo Centroamericano, entre los Mar Caribe 14º y los 18º de latitud norte y los 88º y 92º de longitud oeste. Tiene fronteras al norte con Méjico (960 Km), al oeste con Belice (266 Km), al este con el Mar Caribe Puerto Barrios (148 Km) y Honduras (256 Km), al sudoeste con El Salvador (203 Km) y al sur con Cobán Lago de Izabal el Océano Pacífico (254 Km). -

Guatemalan Society Faces Difficult Dilemma Electing a President

Guatemalan Society Faces Difficult Dilemma Electing a President Supreme Electoral Tribunal in Guatemala called for general elections officially on May 2, 2015. Ahead of the election, the La Linea corruption case involving high-ranking officials of the outgoing administration, including President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti, was made public. The Vice President resigned in May and was arrested on fraud charges in August. More than a dozen ministers and deputy ministers as well as a number of government officials also resigned. Less than a week before the election, President Pérez was also stripped of his immunity, resigned and was arrested. Alejandro Maldonado Aguirre acts as head of state until a new president is sworn into office. On Sunday, October 25, voters will have to choose between a pallid right wing headed by of the former First Lady Sandra Torres, of the National Unity for Hope, and on the other hand Jimmy Morales, of the National Unity Movement, and puppet of a former military group which still dreams of full control of the nation’s society. In the case of Sandra Torres, she already has had a taste of power when her husband, Alvaro Colom, headed a presidency that promised much but gave virtually nothing, especially to the most needy sectors of the Guatemalan society such as the indigenous peoples, with the highest indicators of disease, ignorance and malnutrition and poverty. On his part, candidate Morales is benefiting from the corruption scandal that sent to prison President Otto Pèrez Molina and his wife, Roxana Baldetti. As a new face in the Guatemalan political scene, candidate Morales has grabbed the intention to vote from tens of thousands of indignant Guatemalan voters over prevailing corruption and open graft, which also extends to the congressional ranks. -

Análisis Alternativo Sobre Política Y Economía Febrero 2019

Años 13 y 14 Septiembre 2018 - Nos. 63-64 Análisis alternativo sobre política y economía Febrero 2019 9 88 De élites, “Pacto de Corruptos” y el control del Estado Sobre la cancelación del FCN-Nación y la estrategia en Guatemala pro impunidad y pro corrupción total Si desea apoyar el traba- La publicación del boletín El Observador. Análisis Alternativo jo que hace El Observador, sobre Política y Economía es una de las acciones estratégicas que lleva a puede hacerlo a través de: cabo la Asociación El Observador, como parte de un proceso que promueve • Donaciones la construcción de una sociedad más justa y democrática a través de for- talecer la capacidad para el debate y la discusión, el planteamiento, la pro- • Contactos puesta y la incidencia política de actores del movimiento social guatemal- teco, organizaciones comunitarias y expresiones civiles locales, programas • Información y datos de cooperación internacional, medios de comunicación alternativos, etc., y todas aquellas personas que actúan en distintos niveles (local, regional y • Compra de suscripciones nacional). anuales de nuestras publicaciones ¿Quiénes somos? La Asociación El Observador es una organización civil sin fines lucrativos que está integrada por un grupo de profesionales que están comprometidos y comprometidas con aportar sus conocimientos y ex- periencia para la interpretación de la realidad guatemalteca, particular- 12 calle “A” 3-61 zona 1, ciudad mente de los nuevos ejes que articulan y constituyen la base del actual capital de Guatemala. modelo de acumulación capitalista en Guatemala, las familias oligarcas Teléfono: 22 38 27 21 y los grupos corporativos que le dan contenido, las transnacionales, las fuerzas políticas que lo reproducen en tanto partidos políticos así Puede solicitar esta como agentes en la institucionalidad del Estado, las dinámicas y formas publicación o comunicarse con nosotros, en el correo operativas, ideológicas, políticas y económicas que despliegan en los electrónico: territorios, el Estado y la sociedad en su conjunto. -

Crisis Institucional

Crisis institucional, análisis y pronunciamientos Con el propósito de ofrecer a las y los lectores de la Revista Análisis de la Realidad Nacional una visión panorámica de cómo se está analizando la actual crisis nacional, a continuación se ofrece una selección de posicionamientos institucionales, editoriales y columnas de opinión, publicadas recientemente. “ID Y ENSEÑAD A TODOS“ IPNUSAC Crisis institucional, análisis y pronunciamientos Pronunciamientos Representantes y autoridades estudiantiles de la USAC Ante el Clamor Popular Guatemala 29 de mayo de 2015 Sr. Otto Fernando Pérez Molina. Presidente de la República de Guatemala. Presidente. Como representantes y autoridades estudiantiles de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, siguiendo nuestra obligación de ser portavoces del clamor del movimiento estudiantil le hacemos saber: Que considerando que Guatemala es un país que ha sufrido grandes tragedias en el transcurrir de la historia, las cuales han dañado profundamente a sus habitantes, quienes en su gran mayoría son trabajadores, personas pobres a quienes no es justo dañar con un gobierno corrupto y ladrón que les sigue despojando de sus recursos y oportunidades de progreso. Por lo cual queremos hacer de su conocimiento la siguiente demanda: En vista de que una buena cantidad de las personas de su entera confianza a quienes usted llevó al ejecutivo como funcionarios, se han visto involucrados en actos de corrupción y saqueo a las arcas del Estado, nos unimos a la exigencia, a la petición ciudadana, y gremiales para pedir su renuncia. Esperando que usted atienda nuestra demanda, de manera madura debe separarse del cargo ya que es evidente que no pudo desempeñar satisfactoriamente su labor 2 IPNUSAC Crisis institucional, análisis y pronunciamientos 3 IPNUSAC Crisis institucional, análisis y pronunciamientos Defensa del orden constitucional Consejo Superior Universitario CSU Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala El Consejo Superior Universitario 1. -

1 REPORT to the PERMANENT COUNCIL1 Electoral Observation Mission – Guatemala Presidential, Legislative, Municipal, and Central

REPORT TO THE PERMANENT COUNCIL1 Electoral Observation Mission – Guatemala Presidential, Legislative, Municipal, and Central American Parliamentary Elections September 6 and October 25, 2015 Ambassador Ronald Michael Sanders, Chairman of the Permanent Council Ambassador Luis Raúl Estévez López, Permanent Representative of Guatemala to the OAS Luis Almagro, Secretary General Néstor Méndez, Assistant Secretary General Representatives of Member States and Permanent Observers to the OAS Background On March 16, 2015, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) of Guatemala requested that the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States (OAS) send an Electoral Observation Mission (EOM) to Guatemala for the general elections to be held on September 6 of that year. At these elections, Guatemalan citizens were to elect the President and Vice-President of the Republic, 158 Deputies to the National Congress, 338 Municipal Councils [Corporaciones Municipales], and 20 Deputies for the Central American Parliament. The OAS General Secretariat accepted the request, and Secretary General Luis Almagro appointed Juan Pablo Corlazzoli to head the Mission. A total of 7,556,873 Guatemalans were declared eligible to vote at 19,582 polling stations set up throughout the country. For the presidential elections, 14 pairs of candidates registered to compete for the highest post in the country. The Guatemalan electoral process promised to be complicated. Corruption cases involving top government officials, accusations levelled at candidates at various levels, and an empowered citizenry which took to the streets to hold peaceful demonstrations and express their discontent over the acts of corruption and the political system were some of the elements permeating the election process. On April 16, 2015, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) released a report on the case known as “La Línea,” in which it implicated high government officials. -

Luchas Sociales Y Partidos Políticos En Guatemala

LUCHAS SOCIALES Y PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS EN GUATEMALA Sergio Guerra Vilaboy Primera edición, 2016 Escuela de Ciencia Política de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (ECP) Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos “Manuel Galich” (CELAT) de la ECP Cátedra “Manuel Galich”, Universidad de La Habana (ULH) ISBN Presentación de la edición guatemalteca Para la Escuela de Ciencia Política (ECP) de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC), es una gran satisfacción reeditar un libro que, aunque se escribió hace más de treinta años, no ha perdido su vigencia y, además, ahora se actualiza mediante un apéndice que vuelve a poner en evidencia el rigor científico de su autor, el historiador y profesor cubano, Sergio Guerra Vilaboy. A este libro le fue otorgado el Premio Ensayo, de la Universidad de La Habana, en 1983, lo cual expresa la calidad analítica que está en la base del lúcido enfoque que el autor hace de las dinámicas sociales y partidis- tas de nuestra sociedad, cuando recrea momentos decisivos de nuestro proceso conformador como un país que lucha por ser soberano en el marco de la hegemonía y la dominación geopolítica continental de Es- tados Unidos. Para la ECP, publicar una investigación científica como esta en un mo- mento de crisis de Estado (posiblemente la peor de los últimos treinta años) implica contribuir a la generación de un necesario pensamiento crítico que sirva de base para poder ver de nuevo con esperanza hacia el futuro. Nuestra Escuela, por medio de su Centro de Estudios Latinoa- mericanos “Manuel Galich”, reedita este libro necesario con la esperan- za de que, por medio del ejercicio responsable de las ciencias sociales, nuestros estudiantes y profesores desarrollen su criticidad analítica y su organicidad con los intereses de nuestras mayorías. -

Guatemala Incontext

Guatemala in Context 2018 edition Guatemala in Context 1 ¡Bienvenidos y Bienvenidas! Welcome to Guatemala, a resilient and diverse country brimming with life. Aristotle advises, “If you would understand anything, observe its beginning and its development.” With this in mind, we invite you to embark on a brief journey through Guatemala’s intricate history. As you explore these pages, let go of your preconceptions and watch Guatemala come to life. Reach out and touch the vivid tapestry that is Guatemala. Observe and appreciate the country’s unique and legendary beauty, but don’t stop there. Accept the challenge to look beyond the breathtaking landscapes and rich culture. Look closer. Notice the holes, rips, and snags—tragedy, corruption, and injustice—that consistently work their way into the cloth of Guatemala’s history. Run your fingers over these imperfections. They are as much a part of the weaving as the colorful strings and elaborate patterns, but the heart of the fabric is pliable and resilient. Guatemala hasn’t faded or unraveled over time because the threads of hope are always tightly woven in. We invite you to Published by CEDEPCA Guatemala © become an active participant in working for change, weaving threads of hope and peace, in Guatemala. General Coordinator: Judith Castañeda Edited by: Leslie Vogel, Judith Castañeda, Nancy Carrera Updated by: Hector Castañeda and Kevin Moya Layout and design by: Emerson Morales, Arnoldo Aguilar and Luis Sarpec Revised May 2018 Guatemala 2 in Context 3 Key Moments of Guatemala’s History HOPE1 In the darkest, most sordid, There is a book by Edelberto Torres Rivas, entitled “Interpretation hostile, bitter, of the Central American Social Development”. -

The End of the CICIG Era

1 The End of the CICIG Era An Analysis of the: Outcomes Challenges Lessons Learned Douglas Farah – President - IBI Consultants Proprietary IBI Consultants Research Product 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................5 IMPORTANT POINTS OF MENTION FROM LESSONS LEARNED ...........................................7 OVERVIEW AND REGIONAL CONTEXT ....................................................................................8 THE CICIG EXPERIMENT .......................................................................................................... 11 HISTORY ....................................................................................................................................... 14 THE CICIG’S MANDATE ............................................................................................................. 17 THE ROLE AS A COMPLEMENTARY PROSECUTOR OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ............................. 21 THE IMPACT OF THE CICIG ON CRIMINAL GROUPS ........................................................................ 24 THE CHALLENGES OF THE THREE COMMISSIONERS ........................................................ 27 CASTRESANA: THE BEGINNING ....................................................................................................... 28 DALL’ANESE: THE MIDDLE............................................................................................................ -

Guatemala: Del Estado Burocrático-Autoritario Al Estado Fragmentado

Working Paper Guatemala: del Estado burocrático-autoritario al Estado fragmentado (Guatemala: From the authoritarian bureaucratic state to the fragmented state) Edgar Balsells, Ph.D. Elena Díez Pinto, Ph.D. © 2019 Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. This paper is a work in progress and has not been submitted for editorial review. Índice Introducción ................................................................................................................................... i I. Desarrollo histórico y políticas públicas (1944-1985) .............................................................. 1 1.1 La primavera guatemalteca y la guerra fría (1944-1954) .................................................................. 1 1.2 El Estado Burocrático Autoritario (1954-1985) .................................................................................. 1 1.3 Actores protagonistas del período ......................................................................................................... 4 i. El gobierno de Estados Unidos y su Embajada en Guatemala ........................................ -

The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG)

Crutch to Catalyst? The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala Latin America Report N°56 | 29 January 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. CICIG’s Evolving Mission ................................................................................................. 2 A. Consolidation and Controversy ................................................................................. 2 1. Carlos Castresana ................................................................................................. 2 2. Francisco Dall’Anese ............................................................................................ 4 B. Targeting Corruption – Iván Velásquez .................................................................... 5 III. Scandal and Protest .......................................................................................................... 7 A. “La Línea” .................................................................................................................. -

Enlace De Archivo

Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales GUATEMALA: MONOGRAFÍA DE LOS PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS 2004 – 2008 NIMD FUNDACIÓN KONRAD ADENAUER INSTITUTO HOLANDÉS PARA LA DEMOCRACIA MULTIPARTIDARIA 1 Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales. Departamento de Investigaciones Sociopolíticas Guatemala: monografía de los partidos políticos 2004-2008 Guatemala, 2008 262p. 28cm 1. PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS.- 2. PARTICIPACIÓN POLÍTICA.- 3. FINANCIAMIENTO.- 4. ELECCIONES.- 5. VOTACIÓN.- 6. DIPUTADOS.- 7. ALCALDES.- 8. PARLAMENTO CENTROAMERICANO.- 9. AFILIACIÓN POLÍTICA.- 10. POLÍTICOS.- 11. GUATEMALA. ISBN: 99939-61-33-7 Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales Departamento de Investigaciones Sociopolíticas (DISOP) GUATEMALA: Monografía de los partidos políticos 2004-2008 Coordinación general: Marco Antonio Barahona Equipo DISOP: Ligia Ixmucané Blanco Gabriela Carrera Karin Erbsen de Maldonado Carlos Escobar Armas Zaira Lainez Justo Pérez José Carlos Sanabria Carlos René Vega Fernández Apoyo técnico y administrativo: Amilza Orozco Silvia Rodas Ana María Specher Ciudad Guatemala, Centro América, septiembre de 2008 La elaboración de esta Monografía ha sido posible gracias al apoyo de: Fundación Konrad Adenauer de la República Federal de Alemania (KAS) y Fundación SOROS Guatemala Su publicación y presentación pública han sido posibles gracias al apoyo de: Fundación Konrad Adenauer de la República Federal de Alemania (KAS), Instituto Holandés para la Democracia Multipartidaria (nIMD) y Fundación Soros Guatemala 2 ASOCIACIÓN DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y ESTUDIOS -

El Diálogo “Patriota”

Años 8 y 9, Octubre 2013 - Análisis Alternativo sobre Política y Economía Nos. 42-43 marzo 2014 El diálogo “Patriota” 5 27 55 Criminalización en Modelo de acumulación, La estratagema del diálogo: Guatemala: conflictividad y diálogo Respiración artificial para sujeto, disenso y lucha. una democracia que nació Anotaciones sobre la 88 enferma. Constitución Política de 1985 El diálogo como fetiche La publicación del boletín El Observador. Análisis Alternativo Si desea apoyar el sobre Política y Economía es una de las acciones estratégicas que trabajo que hace El lleva a cabo la Asociación El Observador, como parte de un proceso que Observador, puede promueve la construcción de una sociedad más justa y democrática hacerlo a través de: a través de fortalecer la capacidad para el debate y la discución, el planteamiento social guatemalteco, organizaciones comunitarias y Donaciones expresiones civiles locales, programas de cooperación internacional, medios de comunicación alternativos, etc., y todos aquellos liderazgos Contactos que accionan a distintos niveles (local, regional y nacional). Información y datos ¿Quiénes somos? Compra de suscripciones La Asociación El Observador es una organización civil sin fines anuales de nuestras lucrativos que está integrada por un grupo de profesionales que están publicaciones comprometidos y comprometidas con aportar sus conocimientos y experiencia para la interpretación de la realidad guatemalteca, particularmente de los nuevos ejes que articulan y constituyen la base del actual modelo de acumulación capitalista en Guatemala, las familias oligarcas y los grupos corporativos que le dan contenido, las transnacionales, las fuerzas políticas que lo reproducen en tanto partidos políticos así como en agentes en la institucionalidad del Estado, las dinámicas y formas operativas, ideológicas, políticas y económicas que despliegan en los territorios, el Estado y la sociedad en su conjunto.