Duke University Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Dono Do Morro Dona Marta

4 As formações discursivas em Abusado : o dono do morro Dona Marta A pesquisadora Sandra Moura desenvolveu um vigoroso trabalho sobre o processo de investigação do jornalista Caco Barcellos, especialmente no que concerne a seu segundo livro Rota 66 : a história da polícia que mata. Ao longo do percurso de sua pesquisa, Moura observa a influência do novo jornalismo sobre a produção do jornalista. Segundo Sandra Moura (2007, p. 217), “ Rota 66 tem uma estrutura narrativa não muito comum ao texto jornalístico. Há algo que faz lembrar o andamento literário das grandes reportagens do chamado new journalism ”. E continua: “A análise dos documentos de processo de Rota 66 torna evidente essa presença literária: Ela pode ser localizada bem ali: no planejamento de cenas, nos roteiros e pauta” (Id, p, 217). A pesquisadora aponta a influência de Truman Capote no processo de formação do jornalista brasileiro. Caco Barcellos, por exemplo, leu e releu por inúmeras vezes a obra A sangue frio , com o objetivo de aprender a técnica de apuração dos fatos utilizada por Capote. Outro aspecto na produção do jornalista americano que lhe chamava a atenção era o seu modo de construir a narrativa. Para Sandra Moura (2007), embora Barcellos tenha se apropriado dos ensinamentos deixados por Capote, dentre os adeptos do new journalism , a grande influência de Barcellos parece ter sido Gay Talese, exatamente por o jornalista brasileiro apreciar imensamente o seu “lado cronista”. “Tal influência, certamente, deveu-se à convivência com jornalistas que aderiram no Brasil às técnicas do new journalism , a exemplo de Marcos Faerman, com quem Caco Barcellos trabalhou em Versus na década de 70” (MOURA, 2007, p. -

Descrição Caracterização Ambiental Aspectos Culturais E Históricos Uso

Análise da Região da Unidade de Conservação Descrição Caracterização ambiental Aspectos culturais e históricos Uso e ocupação da terra e problemas ambientais decorrentes Características da população Visão das comunidades sobre a UC Alternativas de desenvolvimento econômico sustentável Legislação municipal pertinente potencial de apoio à UC Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos 2.1 Descrição da área O Parque Nacional da Serra dos Órgãos protege áreas dos municípios de Teresópolis, Petrópolis, Magé e Guapimirim, estando localizado a aproximadamente 16 Km ao norte da Baía de Guanabara, no Estado do Rio de Janeiro. A área considerada nesta análise regional é composta pela área total dos quatro municípios em que está inserido o PARNASO. Os municípios de Petrópolis e Teresópolis estão na região Serrana do estado e Magé e Guapimirim são considerados parte da Região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. O município com maior área na UC é Petrópolis, seguido de Guapimirim e Magé. Teresópolis, apesar de ser o município mais fortemente associado ao parque e de abrigar a sede da unidade, é o município com a menor área no PARNASO (Tabela 2.1). Tabela 2.1: Percentual das Áreas dos municípios no Parque Nacional Serra dos Órgãos. Área do parque Área total do % do por município % do parque município município no Município (em hectares) no município (em hectares) parque Teresópolis 1422 13,34% 772.900 0,18% Petrópolis 4.600 43,18% 796.100 0,58% Magé 1870 17,56% 386.800 0,48% Guapimirim 2761 25,92% 361.900 0,75% Região 10.653 100% 2.317.700 -

Santa Teresa Em Área De Proteção Ambiental (APA), Altera O Regulamento De Zoneamento, Aprovado Pelo Decreto Nº 322, De 3 De Março De 1976, E Dá Outras Providências

D.O. Ano XI nº 76 e 77. parte IV – Terça e Quarta-feira, 23 e 24 de abril de 1985 DECRETO 5.050 DE 23 DE ABRIL DE 1985. REGULAMENTA a Lei n° 495, de 9 de Janeiro de 1984, que transformou o Bairro de Santa Teresa em Área de Proteção Ambiental (APA), altera o Regulamento de Zoneamento, aprovado pelo Decreto nº 322, de 3 de março de 1976, e dá outras providências. O PREFEITO DA CIDADE DO RIO DE JANEIRO, no uso de suas atribuições legais e tendo em vista o que consta do processo n° 02/000.593/84, DECRETA: Art. 1º- O § 1° do art. 163 do Regulamento de Zoneamento aprovado pelo Decreto 322, de 3 de março de 1976, passa a vigorar com a seguinte redação: " Art. 163 - ................................................................................................... § 1° - Fazem parte da Zona Especial - 1 (ZE-1) as áreas acima da curva de nível de 100m (cem metros) delimitados no Anexo 15 C e incluídas na Zona Especial - 3 (ZE-3)." Art. 2º - O Caput do art. 168 do Regulamento de Zoneamanto, passa a vigorar com a seguinte redação: “Art. 168 – Nos lotes existentes na data deste Regulamento, com suas dimensões transcritas no Registro Geral de Imóveis, e naqueles provenientes de desmembramentos efetuados de acordo com o art. 164, com testada para a Rua Boavista (lado ímpar), Estrada das Furnas (entre a Estrada Maracaí e a Estrada do Itapicuru), Estrada do Itapicuru e Estrada do Maracaí é permitida apenas uma edificação residencial unifamiliar nas condições do art. 166 ou uma edificação comercial ou mista de acordo com o estabelecido para Centro de Bairro – 1 (CB-1), atendidos os incisos III, IV e V do art. -

Turismo Cultural No Campo De Santana E Entorno: Um Estudo Sobre a Estação Ferroviária Central Do Brasil No Rio De Janeiro

Caderno Virtual de Turismo ISSN: 1677-6976 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Brasil TURISMO CULTURAL NO CAMPO DE SANTANA E ENTORNO: UM ESTUDO SOBRE A ESTAÇÃO FERROVIÁRIA CENTRAL DO BRASIL NO RIO DE JANEIRO Conceição Lana Fraga, Carla; Silveira Botelho, Eloise; Feigelson Deutsch, Simone; Bogéa Borges, Vera Lúcia TURISMO CULTURAL NO CAMPO DE SANTANA E ENTORNO: UM ESTUDO SOBRE A ESTAÇÃO FERROVIÁRIA CENTRAL DO BRASIL NO RIO DE JANEIRO Caderno Virtual de Turismo, vol. 20, núm. 2, 2020 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=115464354004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18472/cvt.20n2.2020.1843 PDF gerado a partir de XML Redalyc JATS4R Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto Caderno Virtual de Turismo, 2020, vol. 20, núm. 2, ISSN: 1677-6976 Dossiê Temático TURISMO CULTURAL NO CAMPO DE SANTANA E ENTORNO: UM ESTUDO SOBRE A ESTAÇÃO FERROVIÁRIA CENTRAL DO BRASIL NO RIO DE JANEIRO Cultural tourism in Campo de Santana and surrounding area: a study of the Central do Brasil train station in Rio de Janeiro (RJ) Turismo cultural en Campo de Santana y sus alrededores: un estudio sobre la estación de tren Central do Brasil en Río de Janeiro (RJ) Carla Conceição Lana Fraga DOI: https://doi.org/10.18472/cvt.20n2.2020.1843 Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? (UNIRIO), Brasil id=115464354004 [email protected] Eloise Silveira Botelho Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO),, Brasil [email protected] Simone Feigelson Deutsch Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Brasil [email protected] Vera Lúcia Bogéa Borges Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Brasil [email protected] Recepção: 31 Julho 2020 Aprovação: 21 Agosto 2020 Resumo: Nos desafios e oportunidades do patrimônio ferroviário na América Latina no século XXI observa-se que as relações entre memória e patrimônio são chaves. -

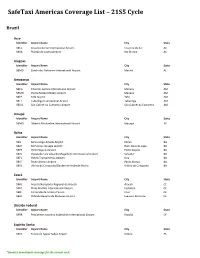

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

População E Território No Antigo Município De Iguaçu (1890/1910)

DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.20947/S0102-3098a0024 Nota de Pesquisa Baixada Fluminense como vazio demográfico? População e território no antigo município de Iguaçu (1890/1910) Lúcia Silva* O município de Iguaçu ocupava o que atualmente é denominado de Baixada Fluminense, englobando o que hoje são os municípios de Belford Roxo, Duque de Caxias, Japeri, Mesquita, Nilópolis, Nova Iguaçu, Queimados e São João de Meriti, com um território que representava 35% da atual região metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro. A noção de Baixada Fluminense unifica o que as emancipações fragmentaram, já que a região no final do século XIX era um município com atividades rurais e, ao longo do século XX, transformou-se em periferia urbana. Chama a atenção a afirmação recorrente dos pesquisadores que estudam a região acerca da existência de um vazio demográfico que teria ocorrido no final do século XIX (1890/1910). O objetivo deste texto é apresentar os principais argumentos utilizados na construção da imagem de vazio demográfico e, com base nos dados obtidos nos censos, oferecer alguns elementos que questionam essa leitura na forma como é enunciada, pois a principal tese é a de que a região da Baixada (como um todo) ficou despovoada e, com as terras vazias, foi ocupada desordenadamente por uma população urbana fugindo dos altos preços da capital federal. Esta leitura recorrente obscurece outras dinâmicas existentes no território, além da própria história da região. Palavras-chave: Baixada Fluminense. População. Ocupação. História. * Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), Nova Iguaçu-RJ, Brasil ([email protected]). R. bras. -

The Politics of Taxation in Argentina and Brazil in the Last Twenty Years of the 20Th Century

THE POLITICS OF TAXATION IN ARGENTINA AND BRAZIL IN THE LAST TWENTY YEARS OF THE 20TH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hiram José Irizarry Osorio, B.S. & M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser ___________________________ Professor Richard P. Gunther Adviser Professor Marcus Kurtz Graduate Program in Political Science ABSTRACT What explains changes in tax policy and its direction and magnitude? More specifically, what explains changes in taxation centralization, progressivity, and level? This dissertation addresses these questions in a comparative way, by studying Argentina and Brazil’s taxation experiences during the 1980s and 1990s. The main reason for choosing these two cases derives from the occurrence of tax policy reforms in both cases, but different in extent and nature, which is the central explanatory concern of this dissertation. Throughout the literature, explanations of change have had a focus on crisis environments, crisis events, and/or agency. Although all of them present some truth and leverage in order to gain an understanding of change taking place, some middle-range explanation is lacking. By this I mean, crises based explanations remain at a high structural level of explanation, while agency based explanations become extremely micro-focused. Though crises present windows of opportunity for changes to take place, they do not guarantee them. Furthermore, changes still have taken place without crises. Thus, crises-based explanations are not necessary or sufficient type of explanations of ii change. -

Metrô + Ônibus De Integração

OLÁ, sabemos que muitas pessoas que participam do Simpósio de Pesquisa Sobre Migrações não conhecem muito bem a região e, por isso, algumas dúvidas podem surgir. Pensando nisso, montamos esse breve guia para te ajudar e para facilitar sua experiência tanto no Campus da Praia Vermelha da UFRJ quanto no Rio de Janeiro. SUMÁRIO 4 Transportes 9 Onde comer? 12 Pontos turísticos 22 Agenda cultural 30 Outras dicas 3 TRANSPORTE Separamos algumas das principais linhas de ônibus que circulam pela Zona Sul e que passam próximas ao Campus da Praia Vermelha. TRO 1 Sai da General Osório (Ipanema), passa pela UFRJ e vai para Central (via Av. Nossa Senhora de Copacabana/ Aterro do Flamengo). * TRO 2 Sai do Jardim de Alah (entre Leblon e Ipanema), passa pela UFRJ Campus Praia Vermelha e segue para rodoviária (via Lapa). * TRO 3 Sai do Leblon, passa pela UFRJ e segue para a Central (via Aterro / Avenida Nossa Senhora de Copacabana). * TRO 4 Sai da Vinicius de Moraes (Ipanema), vai até UFRJ Campus Praia Vermelha e segue para a rodoviária. * 4 TRO 5 Sai do Alto Gávea, passa pela UFRJ e vai para Central (Via Praia de Botafogo). * INT 1 Sai da Barra da Tijuca, mas também passa pelo Alto Leblon e Vieira Souto (Ipanema) e vai para UFRJ, tendo ponto final no Shopping Rio Sul (bem próximo do Campus). * INT 2 Sai da Barra da Tijuca, passa pela Vieira Souto (Ipanema), por Copacabana (Av Atlantida) e segue para a UFRJ, tendo ponto final no Shopping Rio Sul (bem próximo do Campus). * 415 Sai da Cupertino Durão (Leblon), vai para UFRJ e depois segue para o Centro (Central). -

A Comparative Study Between U.S. and Brazilian Acquisition Regulations and Practices Kesia G

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-11-2011 A Comparative Study Between U.S. and Brazilian Acquisition Regulations and Practices Kesia G. Gomes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons Recommended Citation Gomes, Kesia G., "A Comparative Study Between U.S. and Brazilian Acquisition Regulations and Practices" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 1493. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/1493 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN US AND BRAZILIAN ACQUISITION REGULATIONS AND PRACTICES THESIS Kesia G Arraes Gomes, Captain, Brazilian Air Force AFIT/LSCM/ENS/11-04 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. AFIT/LSCM/ENS/11-04 A COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN US AND BRAZILIAN ACQUISITION REGULATIONS AND PRACTICES THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Operational Sciences Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Logistics Management Kesia Guedes Arraes Gomes Captain, Brazilian Air Force March 2011 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. -

Brazil RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: June 2018

Brazil RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: June 2018 JERSEY TRUST COMPANY 0 Executive Summary - Brazil Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries US Dept of State Money Laundering Assessment Higher Risk Areas: Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Serious deficiencies identified in the enacting of counter terrorist financing legislation Non - Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.) World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: coffee, soybeans, wheat, rice, corn, sugarcane, cocoa, citrus; beef Industries: textiles, shoes, chemicals, cement, lumber, iron ore, tin, steel, aircraft, motor vehicles and parts, other machinery and equipment Exports - commodities: transport equipment, iron ore, soybeans, footwear, coffee, autos Exports - partners: China 17%, US 11.1%, Argentina 7.4%, Netherlands 6.2% (2012) Imports - commodities: machinery, electrical and transport equipment, chemical products, oil, automotive parts, electronics Imports - partners: China 15.4%, US 14.7%, Argentina 7.4%, Germany 6.4%, South Korea 4.1% (2012) 1 Investment Restrictions: There are laws that restrict foreign ownership within some sectors, notably aviation, insurance, and media. Foreign investment restrictions remain in a limited number of other sectors, including highway freight (20 percent) and mining of radioactive -

Relação De Postos De Vacinação

SUBPAV/SVS COORDENAÇÃO DO PROGRAMA DE IMUNIZAÇÕES RELAÇÃO DE POSTOS DE VACINAÇÃO CAMPANHA NACIONAL DE VACINAÇÃO ANTI-INFLUENZA 2014 PERÍODO DE 22.04 A 09.05 (2a a 6a feira - SEMANA) N RA POSTO DE VACINAÇÃO ENDEREÇO BAIRRO 1 I CMS JOSÉ MESSIAS DO CARMO RUA WALDEMAR DUTRA 55 SANTO CRISTO 2 I CMS FERNANDO ANTONIO BRAGA LOPES RUA CARLOS SEIDL 1141 CAJÚ 3 II CMS OSWALDO CRUZ RUA HENRIQUE VALADARES 151 CENTRO 4 II CEVAA RUA EVARISTO DA VEIGA 16 CENTRO 5 II PSF LAPA RUA RIACHUELO 43 CENTRO 6 III CMS MARCOLINO CANDAU RUA LAURA DE ARAÚJO 36 CIDADE NOVA 7 III HOSPITAL MUNICIPAL SALLES NETTO PÇA. CONDESSA PAULO DE FRONTIN 52 ESTÁCIO 8 III HOSPITAL CENTRAL DA AERONAUTICA RUA BARÃO DE ITAPAGIBE 167 RIO COMPRIDO 9 III CF SÉRGIO VIEIRA DE MELLO AVENIDA 31 DE MARÇO S/Nº CATUMBI 10 III PSF TURANO RUA AURELIANO PORTUGAL 289 TURANO 11 VII CMS ERNESTO ZEFERINO TIBAU JR. AVENIDA DO EXÉRCITO 01 SÃO CRISTOVÃO 12 VII CF DONA ZICA RUA JOÃO RODRIGUES 43 MANGUEIRA 13 VII IBEX RUA FRANCISCO MANOEL 102 - TRIAGEM BENFICA 14 XXI UISMAV RUA BOM JESUS 40 PAQUETÁ 15 XXIII CMS ERNANI AGRÍCOLA RUA CONSTANTE JARDIM 06 SANTA TERESA 16 IV CMS DOM HELDER CAMARA RUA VOLUNTÁRIOS DA PATRIA, 136 BOTAFOGO 17 IV HOSPITAL ROCHA MAIA RUA GENERAL SEVERIANO, 91 BOTAFOGO 18 IV CMS MANOEL JOSE FERREIRA RUA SILVEIRA MARTINS, 161 CATETE 19 IV CMS SANTA MARTA RUA SÃO CLEMENTE, 312 BOTAFOGO 20 V CF PAVÃO PAVÃOZINHO CANTAGALO RUA SAINT ROMAN, 172 COPACABANA 21 V CMS CHAPEU MANGUEIRA E BABILONIA RUA SÃO FRANCISCO, 5 LEME 22 V CMS JOAO BARROS BARRETO RUA SIQUEIRA CAMPOS, S/Nº COPACABANA 23 VI -

CASES - CYCLE of REGIONAL EVENTS and CONCESSIONS APPS Volume II

CASES - CYCLE OF REGIONAL EVENTS AND CONCESSIONS APPS Volume II Corealization Realization CASES - CYCLE OF REGIONAL EVENTS AND CONCESSIONS APPS Volume II CREDITS CASES - CYCLE OF REGIONAL EVENTS AND CONCESSIONS APPS Volume II Brasília-DF, june 2016 Realization Brazilian Construction Industry Chamber - CBIC José Carlos Martins, Chairman, CBIC Carlos Eduardo Lima Jorge, Chairman, Public Works Committee, CBIC Technical Coordination Denise Soares, Manager, Infrastructure Projects, CBIC Collaboration Geórgia Grace, Project Coordinator CBIC Doca de Oliveira, Communication Coordinator CBIC Ana Rita de Holanda, Communication Advisor CBIC Sandra Bezerra, Communication Advisor CBIC CHMENT Content A T Adnan Demachki, Águeda Muniz, Alex Ribeiro, Alexandre Pereira, André Gomyde, T A Antônio José, Bruno Baldi, Bruno Barral, Eduardo Leite, Elton dos Anjos, Erico Giovannetti, Euler Morais, Fabio Mota, Fernando Marcato, Ferruccio Feitosa, Gustavo Guerrante, Halpher Luiggi, Jorge Arraes, José Atílio Cardoso Filardi, José Eduardo Faria de Azevedo, José João de Jesus Fonseca, Jose de Oliveira Junior, José Renato Ponte, João Lúcio L. S. Filho, Luciano Teixeira Cordeiro, Luis Fernando Santos dos Reis, Marcelo Mariani Andrade, Marcelo Spilki, Maria Paula Martins, Milton Stella, Pedro Felype Oliveira, Pedro Leão, Philippe Enaud, Priscila Romano, Ricardo Miranda Filho, Riley Rodrigues de Oliveira, Roberto Cláudio Rodrigues Bezerra, Roberto Tavares, Rodrigo Garcia, Rodrigo Venske, Rogério Princhak, Sandro Stroiek, Valter Martin Schroeder, Vicente Loureiro, Vinicius de Carvalho, Viviane Bezerra, Zaida de Andrade Lopes Godoy 111 Editorial Coordination Conexa Comunicação www.conexacomunicacao.com.br Copy Christiane Pires Atta MTB 2452/DF Fabiane Ribas DRT/PR 4006 Waléria Pereira DRT/PR 9080 Translation Eduardo Furtado Graphic Design Christiane Pires Atta Câmara brasileira de Indústria e da construção - CBIC SQN - Quadra 01 - Bloco E - Edifício Central Park - 13º Andar CEP 70711-903 - Brasília/DF Tel.: (61) 3327-1013 - www.cbic.org.br © Allrightsreserved 2016.