Brazil RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: June 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Projeto De Lei Do Senado N° 406, De 2015

Atividade Legislativa Projeto de Lei do Senado n° 406, de 2015 Autoria: Senador Paulo Paim (PT/RS) Iniciativa: Ementa: Considera a atividade profissional de motorista de táxi prejudicial à saúde para efeito da concessão de aposentadoria especial. Explicação da Ementa: Considera prejudicial à saúde, para concessão de aposentadoria especial na forma do art. 57, §1º, da Lei nº 8.213/1991, o exercício da atividade profissional de motorista de táxi por período contínuo de 25 anos. Assunto: Política Social - Previdência Social Data de Leitura: 30/06/2015 Em tramitação Decisão: - Último local: - Destino: - Último estado: 11/03/2020 - MATÉRIA COM A RELATORIA Relatoria atual: Relator: Senador Luis Carlos Heinze Matérias Relacionadas: Requerimento nº 790 de 2016 Despacho: Relatoria: 30/06/2015 (Despacho inicial) CAS - (Comissão de Assuntos Sociais) null Relator(es): Senador Romário (encerrado em 07/11/2017 - Audiência de Análise - Tramitação sucessiva outra Comissão) Senador Marcos do Val (encerrado em 03/09/2019 - Alteração (SF-CAS) Comissão de Assuntos Sociais na composição da comissão) Senador Nelsinho Trad (encerrado em 30/10/2019 - 07/11/2017 (Aprovação do Requerimento nº 790, de 2016, de Redistribuição) Aprovação de requerimento Senador Mecias de Jesus (encerrado em 18/12/2019 - Redistribuição) Tramitação Conjunta Senador Luis Carlos Heinze CRA - (Comissão de Agricultura e Reforma Agrária) Análise - Tramitação sucessiva Relator(es): Senador Valdir Raupp (encerrado em 28/02/2018 - (SF-CRA) Comissão de Agricultura e Reforma Agrária Redistribuição) -

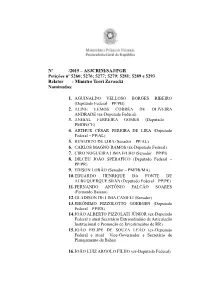

035 Pet5260 E

Nº /2015 – ASJCRIM/SAJ/PGR Petições nº 5260; 5276; 5277; 5279; 5281; 5289 e 5293 Relator : Ministro Teori Zavascki Nominados: 1. AGUINALDO VELLOSO BORGES RIBEIRO (Deputado Federal – PP/PB) 2. ALINE LEMOS CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA ANDRADE (ex-Deputada Federal) 3. ANIBAL FERREIRA GOMES (Deputado – PMDB/CE) 4. ARTHUR CÉSAR PEREIRA DE LIRA (Deputado Federal – PP/AL) 5. BENEDITO DE LIRA (Senador – PP/AL) 6. CARLOS MAGNO RAMOS (ex-Deputado Federal) 7. CIRO NOGUEIRA LIMA FILHO (Senador – PP/PI) 8. DILCEU JOÃO SPERAFICO (Deputado Federal – PP/PR) 9. EDISON LOBÃO (Senador – PMDB/MA) 10. EDUARDO HENRIQUE DA FONTE DE ALBUQUERQUE SILVA (Deputado Federal – PP/PE) 11. FERNANDO ANTÔNIO FALCÃO SOARES (Fernando Baiano) 12. GLADISON DE LIMA CAMELI (Senador) 13. JERÔNIMO PIZZOLOTTO GOERGEN (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 14. JOÃO ALBERTO PIZZOLATI JÚNIOR (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Secretário Extraordinário de Articulação Institucional e Promoção de Investimentos de RR) 15. JOÃO FELIPE DE SOUZA LEÃO (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Vice-Governador e Secretário de Planejamento da Bahia) 16. JOÃO LUIZ ARGOLO FILHO (ex-Deputado Federal) PGR Pet5260 e outras_parlamentares e ex-parlamentares_2 17. JOÃO SANDES JUNIOR (Deputado Federal – PP/GO) 18. JOÃO VACCARI NETO (Tesoureiro do PT) 19. JOSÉ ALFONSO EBERT HAMM (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 20. JOSÉ LINHARES PONTE (ex-Deputado Federal) 21. JOSÉ OLÍMPIO SILVEIRA MORAES (Deputado Federal – PP/SP) 22. JOSÉ OTÁVIO GERMANO (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 23. JOSE RENAN VASCONCELOS CALHEIROS (SENADOR - PMDB-AL) 24. LÁZARO BOTELHO MARTINS (Deputado Federal – PP/TO) 25. LUIS CARLOS HEINZE (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 26. LUIZ FERNANDO RAMOS FARIA (Deputado Federal – PP/MG) 27. -

A “Bolsonarização” Como Produção De Sentido E Mobilização De Afetos

O NEOCONSERVADORISMO RELIGIOSO E HETERONORMATIVIDADE: A “BOLSONARIZAÇÃO” COMO PRODUÇÃO DE SENTIDO E MOBILIZAÇÃO DE AFETOS Elizabeth Christina de Andrade Lima1 Isabelly Cristiany Chaves Lima2 RESUMO: O artigo analisa a construção de narrativas antes e durante a campanha eleitoral para presidente da República do Brasil, em 2018. Tendo como protagonista o agora eleito Presidente Jair Messias Bolsonaro, observamos que sua narrativa é marcada pelos discursos de medo e de ódio dirigidos a todos aqueles que, na sociedade, anta- gonizam com a sua maneira, e de seus apoiadores, para pensar o papel da família, da propriedade e do Estado. Consideramos que tais narrativas ajudaram a construir a sua imagem pública para conseguir a aderência de uma considerável parcela da sociedade que, doravante, orgulha-se em se identificar como de direita, conservadora, favorável à família, à moral e aos bons costumes. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Neoconservadorismo. Bolsonarização. Heteronormatividade. Produção de sentidos e de afetos. NEOCONSERVATORISM IN RELIGION AND HETERONORMATIVITY: “BOLSONARIZAÇÃO” AS PRODUCTION OF MEANING AND MOBILIZATION OF AFFECTS ABSTRACT: The article analyzes the construction of narratives before and during the Presidential campaign for the Republic of Brazil, in 2018. We note that the narrative of the 1 Universidade Federal de Campina Grande (UFCG), Campina Grande – PB – Brasil. Professora Titular de Antropologia. Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza – CE – Brasil. Doutora em Sociologia. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3072-3624. [email protected]. 2 Universidade Federal de Campina Grande (UFCG), Campina Grande – PB – Brasil. Doutoranda pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9787-7604. [email protected]. -

From Squatter to Seller

From Squatter to Settler: Applying the Lessons of Nineteenth Century U.S. Public Land Policy to Twenty-first Century Land Struggles in Brazil Jessica Intrator* Brazil's policies affecting its land in the Amazon region have assumed global significance, in part due to the pressing realitiesof deforestation and climate change. Domestically, the allocation and utilization of Amazonian land has important implicationsfor Brazil's social and political stability, economic development, environmental conservation efforts, and cultural preservation efforts. The area known as the "legal Amazon" for planning purposes comprises more than 57 percent of Brazil's national territory; the manner of settlement and occupation of land in this region is a contentious issue. This Note explores the history of public land settlement in the Brazilian Amazon and the recent debates in Brazil over a federal law that enables about 300,000 current occupants of public land in the legal Amazon to acquire legal title. For perspective, the Note compares the potentialconsequences of this law to those of a series of retrospective titling laws passed in the United States during the half century leading up to the Homestead Act. The U.S. preemption laws sought to provide the opportunity for squatters on the U.S. public lands to acquire title without Copyright @ 2011 Regents of the University of California. Jessica Intrator is currently a research fellow at Berkeley Law's Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. Following her fellowship, she will serve as judicial law clerk to the Honorable Magistrate Judge Paul S. Grewal of the Northern District of California, and then will join the firm of Nixon Peabody LLP as an associate. -

The Politics of Taxation in Argentina and Brazil in the Last Twenty Years of the 20Th Century

THE POLITICS OF TAXATION IN ARGENTINA AND BRAZIL IN THE LAST TWENTY YEARS OF THE 20TH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hiram José Irizarry Osorio, B.S. & M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser ___________________________ Professor Richard P. Gunther Adviser Professor Marcus Kurtz Graduate Program in Political Science ABSTRACT What explains changes in tax policy and its direction and magnitude? More specifically, what explains changes in taxation centralization, progressivity, and level? This dissertation addresses these questions in a comparative way, by studying Argentina and Brazil’s taxation experiences during the 1980s and 1990s. The main reason for choosing these two cases derives from the occurrence of tax policy reforms in both cases, but different in extent and nature, which is the central explanatory concern of this dissertation. Throughout the literature, explanations of change have had a focus on crisis environments, crisis events, and/or agency. Although all of them present some truth and leverage in order to gain an understanding of change taking place, some middle-range explanation is lacking. By this I mean, crises based explanations remain at a high structural level of explanation, while agency based explanations become extremely micro-focused. Though crises present windows of opportunity for changes to take place, they do not guarantee them. Furthermore, changes still have taken place without crises. Thus, crises-based explanations are not necessary or sufficient type of explanations of ii change. -

Direitos Políticos, Liberdade De Expressão E Discurso De Ódio

A R EI R E Vivemos a era da polarização. No cenário político bra- P RODOLFO VIANA PEREIRA O Instituto para o Desenvolvi- ORGANIZADOR R sileiro – e por que não mundial –, a impressão é a de IANA ORGANIZADOR mento Democrático (IDDE), é que não há espaço para consensos e de que as claques V RODOLFO VIANA PEREIRA voltado para a concepção, or- se entrincheiram cada vez mais, com vozes ampliadas GANIZADO R ODOLFO ganização e execução de proje- no ecossistema virtual das redes sociais. E esse movi- O R Doutor em Ciências Jurídico-Políticas mento traz consigo a radicalização das opiniões, im- pela Universidade de Coimbra. Mestre tos de formação e consultoria DIREITOS POLÍTICOS, em Direito Constitucional pela UFMG. pulsionando discursos virulentos, abjetos, discrimina- em Gestão Pública, Direito, Pós-Graduado em Direito Eleitoral e tórios. Desenvolvimento socioeconô- LIBERDADE DE EXPRESSÃO Administração de Eleições pela Uni- versidade de Paris II. Pós-Graduado em mico e Democracia. Pensar o papel do Direito (e também do Direito Polí- Educação a Distância pela Universidade tico) nesse contexto não é tarefa simples. Apesar de a E DISCURSO DE ÓDIO da Califórinia, Irvine. Professor da Fa- culdade de Direito da UFMG. Advogado Destinado a fortalecer os pila- doutrina nacional e estrangeira já ter avançado muito Volume I sócio da MADGAV Advogados. Funda- res do Estado Democrático de na definição e na conceituação dos chamados “discur- sos de ódio”, seu enquadramento concreto e conse- dor e diretor da SmartGov – Governan- Direito, presta serviços para ór- ça Criativa. Fundador e primeiro coor- quências legais daí advindas ainda transitam em uma gãos públicos e privados com denador-geral da ABRADEP. -

Macro Report Brazilian Electotal Study, 2010 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3: Macro Report

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 3: Macro Report Brazilian Electotal Study, 2010 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3: Macro Report Country: Brazil Date of Election: October 3st , 2010 (1 st round); October, 31 st , 2010 (2 nd round) Prepared by: Rachel Meneguello Date of Preparation: 15/11/2011 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative [X ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: ____also state governors______ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [ X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __also for state legislatives_______ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 3: Macro Report Brazilian Electotal Study, 2010 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election? Partido dosTrabalhadores (Workers Party) . -

Duke University Dissertation Template

‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Urban Black Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense by Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Migolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT ‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Black Urban Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense By Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Mignolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Stephanie Virginia Reist 2018 Abstract “Even Christ the Redeemer has turned his back to us” a young, Black female resident of the Baixada Fluminense told me. The 13 municipalities that make up this suburban periphery of -

Elenão: Economic Crisis, the Political Gender Gap, and the Election of Bolsonaro

Ibero-Amerika Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Instituto Ibero-Americano de Investigaciones Económicas Ibero-America Institute for Economic Research (IAI) Georg-August-Universität Göttingen (founded in 1737) Diskussionsbeiträge · Documentos de Trabajo · Discussion Papers Nr. 242 #EleNão: Economic crisis, the political gender gap, and the election of Bolsonaro Laura Barros, Manuel Santos Silva August 2019 Platz der Göttinger Sieben 3 37073 Goettingen Germany Phone: +49-(0)551-398172 Fax: +49-(0)551-398173 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.iai.wiwi.uni-goettingen.de #EleNão: Economic crisis, the political gender gap, and the election of Bolsonaro Laura Barros1 and Manuel Santos Silva1 1University of Goettingen This version: August 9, 2019. Abstract After more than one decade of sustained economic growth, accompanied by falling poverty and inequality, Brazil has been hit by an economic recession starting in 2014. This paper investigates the consequences of this labor market shock for the victory of far-right Jair Bolsonaro in the 2018 presidential election. Using a shift- share approach and exploring the differential effects of the recession by gender and race, we show that heterogeneity in exposure to the labor demand shock by the different groups is a key factor explaining the victory of Bolsonaro. Our results show that male-specific labor market shocks increase support for Bolsonaro, while female-specific shocks have the opposite effect. Interestingly, we do not find any effect by race. We hypothesize that, once facing economic insecurities, men feel more compelled to vote for a figure that exacerbates masculine stereotypes, as a way of compensating for the loss in economic status. -

Sem Título-2

1 SECRETARIA DA COORDENAÇÃO E PLANEJAMENTO ISSN 1676-4994 FUNDAÇÃO DE ECONOMIA E ESTATÍSTICA ISBN 85-7173-015-6 Siegfried Emanuel Heuser A Fundação de Economia e Estatística Siegfried Emanuel Heuser (FEE) tem estimulado e apoiado as iniciati- vas de aprimoramento técnico e acadêmico de seus pesquisadores! Dentro dessa perspectiva, a titulação representa a elevação do patamar de competência do corpo técnico e, também, um elemento estratégico frente às exigências institucionais que se colocam no campo da produção de conhecimento! Na última década, o esforço coletivo da FEE tem se direcionado para o doutorado! A série Teses FEE foi criada para divulgar as teses de Doutorado recentemente produzidas pelos pesquisadores da FEE! AS MEDIAÇÕES CRUCIAIS DAS MUDANÇAS POLÍTICO-INSTITUCIONAIS NAS TELECOMUNICAÇÕES DO BRASIL Renato Antônio Dalmazo Menção honrosa no VIII Prêmio Brasil de Economia, na categoria Livro/Tese de Doutorado, promovido pelo Conselho Federal de Economia, em 2001& TESES FEE Nº 2 Porto Alegre, novembro de 2002 2 Secretaria da Coordenação e Planejamento FUNDAÇÃO DE ECONOMIA E ESTATÍSTICA Siegfried Emanuel Heuser CONSELHO DE PLANEJAMENTO: Presidente: José Antonio Fialho Alonso Membros: André Meyer da Silva, Ernesto Dornelles Saraiva, Ery Bernardes, Eudes Antidis Missio, Nelson Machado Fagundes e Ricardo Dathein CONSELHO CURADOR: Fernando Luiz M dos Santos, Francisco Hypólito da Silveira e Suzana de Medeiros Albano DIRETORIA: PRESIDENTE: JOSÉ ANTONIO FIALHO ALONSO DIRETOR TÉCNICO: FLÁVIO B FLIGENSPAN DIRETOR ADMINISTRATIVO: CELSO -

Realinhamentos Partidários No Estado Do Rio De Janeiro (1982-2018) Theófilo Codeço Machado Rodrigues1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7984.2020.e67408 Realinhamentos partidários no estado do Rio de Janeiro (1982-2018) Theófilo Codeço Machado Rodrigues1 Resumo O presente artigo investiga o processo de realinhamento partidário em curso no estado do Rio de Janeiro. Foram observados os partidos dos governadores e senadores eleitos no Rio de Janeiro pelo voto direto entre 1982 e 2018. Além dos governadores, foram avaliadas as bancadas partidá- rias eleitas para a Assembleia Legislativa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (ALERJ) e para a Câmara dos Deputados durante todo o período. A pesquisa confirmou a hipótese do recente realinhamento partidário no Rio de Janeiro e identificou que, com o declínio eleitoral do brizolismo, e com a prisão das principais lideranças locais do PMDB a partir de 2016, o tradicional centro político do estado – PDT pela centro-esquerda e PMDB pela centro-direita – implodiu e novos partidos oriundos dos extremos do espectro político emergiram como PSL, PRB e PSC, pela direita, e PSOL, pela esquerda. Palavras-chave: Partidos Políticos. Rio de Janeiro. Sistema Partidário. Brizolismo. Chaguismo. 1 Introdução Entre 1982 e 2018, houve no Rio de Janeiro sete governadores eleitos pelo voto direto e três vice-governadores que assumiram o cargo. No de- curso desse período, verifica-se que o PMDB governou o estado durante 19 anos, o PDT por 10, o PSDB por 4, o PSB por 2 e o PT por alguns meses. Em outubro de 2018, um novo partido foi eleito para o governo: o PSC. Nas décadas de 1980 e 1990, Brizola, brizolistas e ex-brizolistas protagonizaram a política no estado. -

Market Research Expoort Free 6101 Brazil

Market research Men's or boys' overcoats, car coats, capes, cloaks, anoraks (including ski jackets), windcheaters, wind-jackets and similar articles, knitted or crocheted, other than those of heading 6103 Product Code: 6101 Brazil June 2014 The Free-Expoort report is only available in English. Additionally we offer the 6-Digits report that is available with the following languages: French, German, Italian and Spanish. The 6-Digits report offers improvements that can be found on the following link www.expoort.com Index 1. Overview of Brazil..........................................................3 1.1. Economic Information......................................................4 1.2. Policy and country risk Information.......................................6 1.3. Demographic Information...................................................7 2. Demand Information .............................9 2.1 Potential demand for the HS 6101 product.............................10 3. Supply information .............................12 3.1. Business directories and emarketplaces .............................12 3.2. Trade fairs and shows .............................13 4. Market access .............................16 4.1. Tariffs and taxes .............................16 4.2. Customs documentation .............................16 4.3. Trade barriers .............................17 4.4. Commercial and trade laws .............................17 4.5. Patents and trademarks .............................18 5. Other countries with opportunity for the HS 6101 product.............................19