From Squatter to Seller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Projeto De Lei Do Senado N° 406, De 2015

Atividade Legislativa Projeto de Lei do Senado n° 406, de 2015 Autoria: Senador Paulo Paim (PT/RS) Iniciativa: Ementa: Considera a atividade profissional de motorista de táxi prejudicial à saúde para efeito da concessão de aposentadoria especial. Explicação da Ementa: Considera prejudicial à saúde, para concessão de aposentadoria especial na forma do art. 57, §1º, da Lei nº 8.213/1991, o exercício da atividade profissional de motorista de táxi por período contínuo de 25 anos. Assunto: Política Social - Previdência Social Data de Leitura: 30/06/2015 Em tramitação Decisão: - Último local: - Destino: - Último estado: 11/03/2020 - MATÉRIA COM A RELATORIA Relatoria atual: Relator: Senador Luis Carlos Heinze Matérias Relacionadas: Requerimento nº 790 de 2016 Despacho: Relatoria: 30/06/2015 (Despacho inicial) CAS - (Comissão de Assuntos Sociais) null Relator(es): Senador Romário (encerrado em 07/11/2017 - Audiência de Análise - Tramitação sucessiva outra Comissão) Senador Marcos do Val (encerrado em 03/09/2019 - Alteração (SF-CAS) Comissão de Assuntos Sociais na composição da comissão) Senador Nelsinho Trad (encerrado em 30/10/2019 - 07/11/2017 (Aprovação do Requerimento nº 790, de 2016, de Redistribuição) Aprovação de requerimento Senador Mecias de Jesus (encerrado em 18/12/2019 - Redistribuição) Tramitação Conjunta Senador Luis Carlos Heinze CRA - (Comissão de Agricultura e Reforma Agrária) Análise - Tramitação sucessiva Relator(es): Senador Valdir Raupp (encerrado em 28/02/2018 - (SF-CRA) Comissão de Agricultura e Reforma Agrária Redistribuição) -

Votação Aberta 56 ª Legislatura Quórum Qualificado 3ª Sessão Legislativa Ordinária Proposta De Emenda À Constituição Nº 6, De 2018, Nos Termos Do Parecer (1º Turno)

Senado Federal Votação Aberta 56 ª Legislatura Quórum Qualificado 3ª Sessão Legislativa Ordinária Proposta de Emenda à Constituição nº 6, de 2018, nos termos do Parecer (1º Turno) Altera o art. 12 da Constituição Federal, para suprimir a perda de nacionalidade brasileira em razão da mera naturalização, incluir a exceção para situações de apatridia, e acrescentar a possibilidade de a pessoa requerer a perda da própria nacionalidade. Matéria PEC 6/2018 Início Votação 15/06/2021 16:51:35 Término Votação 15/06/2021 17:21:44 Sessão 65º Sessão Deliberativa Remota Data Sessão 15/06/2021 16:00:00 Partido Orientação MDB SIM PSD SIM Podemos SIM PSDB SIM PROGRES SIM DEM SIM PT SIM PL SIM PROS SIM Republica SIM Patriota SIM Minoria SIM Governo SIM Banc Fem SIM Partido UF Nome Senador Voto PDT RO Acir Gurgacz SIM Cidadania SE Alessandro Vieira SIM Podemos PR Alvaro Dias SIM PSD BA Angelo Coronel SIM PSD MG Antonio Anastasia SIM PSD MT Carlos Fávaro SIM PL RJ Carlos Portinho SIM PSD MG Carlos Viana SIM DEM RR Chico Rodrigues SIM PROGRES PI Ciro Nogueira SIM MDB RO Confúcio Moura SIM PROGRES PB Daniella Ribeiro SIM MDB SC Dário Berger SIM DEM AP Davi Alcolumbre SIM Podemos CE Eduardo Girão SIM MDB TO Eduardo Gomes SIM Cidadania MA Eliziane Gama SIM PROGRES PI Elmano Férrer SIM PROGRES SC Esperidião Amin SIM REDE ES Fabiano Contarato SIM Emissão 15/06/2021 17:21:46 Senado Federal Votação Aberta 56ª Legislatura Quórum Qualificado 3ª Sessão Legislativa Ordinária Proposta de Emenda à Constituição nº 6, de 2018, nos termos do Parecer (1º Turno) Altera o art. -

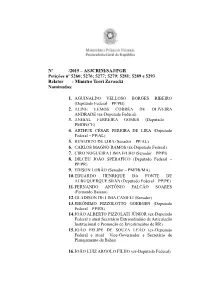

035 Pet5260 E

Nº /2015 – ASJCRIM/SAJ/PGR Petições nº 5260; 5276; 5277; 5279; 5281; 5289 e 5293 Relator : Ministro Teori Zavascki Nominados: 1. AGUINALDO VELLOSO BORGES RIBEIRO (Deputado Federal – PP/PB) 2. ALINE LEMOS CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA ANDRADE (ex-Deputada Federal) 3. ANIBAL FERREIRA GOMES (Deputado – PMDB/CE) 4. ARTHUR CÉSAR PEREIRA DE LIRA (Deputado Federal – PP/AL) 5. BENEDITO DE LIRA (Senador – PP/AL) 6. CARLOS MAGNO RAMOS (ex-Deputado Federal) 7. CIRO NOGUEIRA LIMA FILHO (Senador – PP/PI) 8. DILCEU JOÃO SPERAFICO (Deputado Federal – PP/PR) 9. EDISON LOBÃO (Senador – PMDB/MA) 10. EDUARDO HENRIQUE DA FONTE DE ALBUQUERQUE SILVA (Deputado Federal – PP/PE) 11. FERNANDO ANTÔNIO FALCÃO SOARES (Fernando Baiano) 12. GLADISON DE LIMA CAMELI (Senador) 13. JERÔNIMO PIZZOLOTTO GOERGEN (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 14. JOÃO ALBERTO PIZZOLATI JÚNIOR (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Secretário Extraordinário de Articulação Institucional e Promoção de Investimentos de RR) 15. JOÃO FELIPE DE SOUZA LEÃO (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Vice-Governador e Secretário de Planejamento da Bahia) 16. JOÃO LUIZ ARGOLO FILHO (ex-Deputado Federal) PGR Pet5260 e outras_parlamentares e ex-parlamentares_2 17. JOÃO SANDES JUNIOR (Deputado Federal – PP/GO) 18. JOÃO VACCARI NETO (Tesoureiro do PT) 19. JOSÉ ALFONSO EBERT HAMM (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 20. JOSÉ LINHARES PONTE (ex-Deputado Federal) 21. JOSÉ OLÍMPIO SILVEIRA MORAES (Deputado Federal – PP/SP) 22. JOSÉ OTÁVIO GERMANO (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 23. JOSE RENAN VASCONCELOS CALHEIROS (SENADOR - PMDB-AL) 24. LÁZARO BOTELHO MARTINS (Deputado Federal – PP/TO) 25. LUIS CARLOS HEINZE (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 26. LUIZ FERNANDO RAMOS FARIA (Deputado Federal – PP/MG) 27. -

Brazil RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: June 2018

Brazil RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: June 2018 JERSEY TRUST COMPANY 0 Executive Summary - Brazil Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries US Dept of State Money Laundering Assessment Higher Risk Areas: Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Serious deficiencies identified in the enacting of counter terrorist financing legislation Non - Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.) World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: coffee, soybeans, wheat, rice, corn, sugarcane, cocoa, citrus; beef Industries: textiles, shoes, chemicals, cement, lumber, iron ore, tin, steel, aircraft, motor vehicles and parts, other machinery and equipment Exports - commodities: transport equipment, iron ore, soybeans, footwear, coffee, autos Exports - partners: China 17%, US 11.1%, Argentina 7.4%, Netherlands 6.2% (2012) Imports - commodities: machinery, electrical and transport equipment, chemical products, oil, automotive parts, electronics Imports - partners: China 15.4%, US 14.7%, Argentina 7.4%, Germany 6.4%, South Korea 4.1% (2012) 1 Investment Restrictions: There are laws that restrict foreign ownership within some sectors, notably aviation, insurance, and media. Foreign investment restrictions remain in a limited number of other sectors, including highway freight (20 percent) and mining of radioactive -

Ceará Titulares Sen

Ceará Titulares Sen. Eunício Oliveira (PMDB/CE) Nome civil: Eunício Lopes de Oliveira Data de nascimento: 30/09/1952 Partido / UF: PMDB / CE Naturalidade: Lavras da Mangabeira (CE) Endereço parlamentar: Anexo I, 17º Andar Telefones: (61) 3303-6245 FAX: (61) 3303-6253 Correio eletrônico: [email protected] Sen. José Pimentel (PT/CE) Nome civil: José Barroso Pimentel Data de nascimento: 16/10/1953 Partido / UF: PT / CE Naturalidade: Picos (PI) Endereço parlamentar: Ala Filinto Müller gab. 13 Telefones: (61) 3303-6390 /6391 FAX: (61) 3303-6394 Correio eletrônico: [email protected] Rio de Janeiro Titulares Sen. Francisco Dornelles (PP/RJ) Nome civil: Francisco Oswaldo Neves Dornelles Data de nascimento: 07/01/1935 Partido / UF: PP / RJ Naturalidade: Belo Horizonte (MG) Endereço parlamentar: Ala Senador Teotônio Vilela, gab. 11 Telefones: (61) 3303-4229 FAX: (61) 3303-2896 Correio eletrônico: [email protected] PMDB/RJ Deputado Eduardo Cunha Nome civil: EDUARDO COSENTINO DA CUNHA Aniversário: 29 / 9 - Profissão: ECONOMISTA Partido/UF: PMDB / RJ / Titular Telefone: (61) 3215-5510 - Fax: 3215-2510 Legislaturas: 03/07 07/11 11/15 Suplentes Dep. Walney Rocha (PTB/RJ) Nome civil: WALNEY DA ROCHA CARVALHO Aniversário: 19 / 4 - Profissão: Servidor Público Estadual Partido/UF: PTB / RJ / Titular Telefone: (61) 3215-5644 - Fax: 3215-2644 Legislaturas: 11/15 Dep. Glauber Braga (PSB/RJ) Nome civil: GLAUBER DE MEDEIROS BRAGA Aniversário: 26 / 6 - Profissão: Bacharel em Direito Partido/UF: PSB / RJ / Titular Telefone: (61) 3215-5362 - Fax: 3215-2362 Legislaturas: 07/11 11/15 Acre Titular Sen. Sérgio Petecão (PSD/AC) Nome civil: Sérgio de Oliveira Cunha Data de nascimento: 20/04/1960 Partido / UF: PSD / AC Naturalidade: Rio Branco (AC) Endereço parlamentar: Ala Teotonio Vilela gab. -

Lava Jato Investiga Pessoas Ligadas a 5 Senadores E Governador De

B2 POLÍTICA SALVADOR QUARTA-FEIRA 22/3/2017 Edilson Lima / Ag. A TARDE Delações vão atingir quase um terço dos ministros GABRIELA VALENTE, JAILTON DE CARVALHO E TIAGO DANTAS Agência O Globo, Brasília e São Paulo A delação dos ex-executivos da Obebrecht vai atingir quase um terço do primeiro escalão do governo Michel Temer, o que deve agravar a crise política na Esplanada dos Ministérios. O peeme- debista já determinou, po- rém, que seus ministros só deixarão o governo caso se- jam tornados réus em ações penais. Nove ministros são alvo de pedido de abertura de in- quérito junto ao Supremo Tribunal Federal por conta dos depoimentos dos cola- boradores da empreiteira. O jornal Valor Econômico revelou, ontem, que entre os nove ministros estaria oti- Policiais federais estiveram ontem no condomínio Reserva Albalonga, no Horto Florestal, em Salvador, um dos alvos da operação tular da Agricultura, Blairo Maggi. Ainformação foi confirmada pelo Globo. Além dele, estão na lista OPERAÇÃO DA PF Buscas e apreensões em cinco estados foram autorizadas pelo ministro Fachin de pedidos de inquérito do procurador-geral da Repú- blica, Rodrigo Janot, os mi- nistros Eliseu Padilha (Casa Civil), Moreira Franco (Se- Lava Jato investiga pessoas ligadas a 5 cretaria-Geral), Aloysio Nu- nes (Relações Exteriores), Bruno Araújo (Cidades), Gil- berto Kassab (Ciência e Tec- senadores e governador de Alagoas nologia), eMarcos Pereira (Desenvolvimento). Outrosdoisministrosain- AGÊNCIA O GLOBO Casa; Valdir Raupp localizado no Horto Flores- Uma das buscas foirea- ce o teor da nova fase da Lava da estão na lista, mas os no- Pernambuco (PDMB-RO), Humberto Cos- tal, bairro nobre da capital lizada em Brasília, na em- Jato. -

Estado Nome Do Senador Partido Conta No Twitter E-Mail AC Mailza Gomes PSD @Mailzagomes [email protected] AC Marcio

Estado Nome do Senador Partido Conta no Twitter E-mail AC Mailza Gomes PSD @MailzaGomes [email protected] AC Marcio Bittar MDB @marciombittar [email protected] AC Sérgio Petecão PP @senadorpetecao [email protected] AL Fernando Collor PROS @Collor [email protected] AL Renan Calheiros MDB @renancalheiros [email protected] AL Rodrigo Cunha PSDB @RodrigoCunhaAL [email protected] AM Eduardo Braga MDB @EduardoBraga_AM [email protected] AM Omar Aziz PSD @OmarAzizPSD [email protected] AM Plínio Valério PSDB @PlinioValerio45 [email protected] AP Davi Alcolumbre DEM @davialcolumbre [email protected] AP Lucas Barreto PSD @LucasBarreto_AP [email protected] AP Randolfe Rodrigues REDE @randolfeap [email protected] BA Angelo Coronel PSD @angelocoronel_ [email protected] BA Jaques Wagner PT @jaqueswagner [email protected] BA Otto Alencar PSD @ottoalencar [email protected] CE Cid Gomes PDT @senadorcidgomes [email protected] CE Eduardo Girão PODEMOS @EduGiraoOficial [email protected] CE Tasso Jereissati PSDB @tassojereissati [email protected] DF Izalci Lucas PSDB @IzalciLucas [email protected] DF Leila Barros PSB @leiladovolei [email protected] DF Reguffe PODEMOS @Reguffe [email protected] ES Fabiano Contarato REDE @ContaratoSenado [email protected] ES Marco do Val PODEMOS -

The Vice President and Impeachment

Waiting in the Wings: The Vice President and Impeachment By Mark Langevin, Senior Research Fellow and Aléxia Monteiro, Research Associate Council on Hemispheric Affairs Vice-President Michel Temer now waits in the wings ready to take charge of Brazil's federal government. His party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB), the country's largest, just announced its departure from President Dilma Rousseff’s governing coalition. With one momentary exception, the PMDB has participated in every government since the return to civilian rule in 1985. In 1992 it bolted from then President Fernando Collor’s cabinet just weeks before his impeachment. Today, the PMDB stands ready to support President Dilma's impeachment, paving the way for Temer to be sworn in as chief executive of a polarized nation in a deep recession. It is unlikely he can lead Brazil to overcome its economic and political challenges. Rather, Temer's succession to the presidency may compound them by widening political polarization and raising concerns about his own role in political corruption, including the Lava Jato scheme.1 Vice-President Temer is a lawyer and professor of constitutional law with a long history in elective office. He served six consecutive terms as a congressional representative in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies and was its president from 1997 to 2000 and again from 2009 to 2010 before being selected as Dilma Rousseff’s running mate. He is president of the PMDB. Most important, he has been identified, through plea-bargained testimony, as having played a role in the Lava Jato corruption scheme. 2 Temer’s standing as vice-president and president in waiting is jeopardized by the Lava Jato scandal as well as the case under consideration at Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE). -

PROJETO DE LEI ORÇAMENTÁRIA PARA 2018 (Projeto De Lei N° 20/2017 -CN)

Corr 1s.iã:J Ml ~a de Planos, Orçamentos Publicos e Fiscalização PROJETO DE LEI ORÇAMENTÁRIA PARA 2018 (Projeto de Lei n° 20/2017 -CN) RECIBOS DE ENTREGA E ATAS DAS EMENDAS COLETIVAS Comissões Permanentes do Senado Federal 1. Comissão de Agricultura e Reforma Agrária 2. Comissão de Assuntos Econômicos 3. Comissão de Assuntos Sociais 4. Comissão de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovação 5. Comissão de Constituição, Justiça e Cidadania 6. Comissão de Desenvolvimento Regional e Turismo 7. Comissão de Direitos Humanos e Legislação Participativa 8. Comissão Diretora do Senado Federal 9. Comissão de Educação, Cultura e Esporte 1O. Comissão de Meio Ambiente 11. Comissão de Relações Exteriores e Defesa Nacional 12. Comissão Senado do Futuro 13. Comissão de Serviços de Infraestrutura 14. Comissão de Transparência, Governança, Fiscalização e Controle e Defesa do Consumidor Data: 10/10/2017 CONGRESSO NACIONAL COMISSÃO MISTA DE PLANOS, ORÇAMENTOS E FISCALIZAÇÃO Hora: 13:04 SISTEMA DE ELABORAÇÃO DE EMENDAS ÀS LEIS ORÇAMENTÁRIAS Página: 1 de 1 PLN 0020 I 2017 - LOA RECIBO DE ENTREGA DE EMENDAS À LOA ------------------------- EMENDA DE REMANEJAMENTO DE DESPESA NÚMERO UO TÍTULO LOCALIDADE VALOR DO EMENDA ACRÉSCIMO EMENDA DE APROPRIAÇÃO DE DESPESA NÚMERO UO TÍTULO LOCALIDADE VALOR DO EMENDA ACRÉSCIMO 1 22101 Fomento ao Setor Agropecuário - Nacional Nacional-NA 500.000.000 2 20129 Regularização da Estrutura Fundiária na Nacional-NA 400.000.000 Área de Abrangência da Lei 11.952, de 2009 - A presente emenda destina-se a Regularização da Estrutura Fundiária na Área de Abrangência da Lei 11.952, de 2009 - Nacional 3 47205 Censos Demográfico e Agropecuário - Censo Nacional-NA 400.000.000 Demográfico e Agropecuário - Nacional 4 22202 Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento de Tecnologias Nacional-NA 300.000.000 para a Agropecuária - Nacional EMENDA DE CANCELAMENTO DE DESPESA NÚMERO SEQUENCIAL TÍTULO VALOR DO CANCELAMENTO Quantidade Valor Total de Emendas de Apropriação de Despesa 4 1. -

Atividade Legislativa Projeto De Lei Do Senado N° 279, De 2015

Atividade Legislativa Projeto de Lei do Senado n° 279, de 2015 Autoria: Senador Romário (PSB/RJ) Iniciativa: Ementa: Altera a Lei nº 9.615, de 24 de março de 1998, para atribuir direito à aposentadoria especial ao atleta profissional e regular a atividade de prática desportiva profissional em entidades de prática desportiva de todas as modalidades esportivas. Explicação da Ementa: Altera a Lei nº 9.615, de 24 de março de 1998, para dispor que estender ao atleta profissional a aposentadoria especial, nos termos do art. 57 da Lei nº 8.213, de 4 de julho de 1991, segundo critérios estabelecidos pelo Poder Executivo. Dispõe que a vedação da participação em competições desportivas profissionais de atletas não-profissionais com idade superior a vinte anos será obrigatória exclusivamente para atletas e entidades de prática profissional da modalidade de futebol. Assunto: Política Social - Desporto e Lazer Data de Leitura: 12/05/2015 Em tramitação Decisão: - Último local: - Destino: - Último estado: 27/03/2019 - MATÉRIA COM A RELATORIA Relatoria atual: Relator: Senadora Leila Barros Matérias Relacionadas: Requerimento nº 790 de 2016 Requerimento nº 121 de 2018 Despacho: Relatoria: 12/05/2015 (Despacho inicial) CE - (Comissão de Educação, Cultura e Esporte) null Relator(es): Senador Alvaro Dias (encerrado em 09/03/2016 - Audiência de Análise - Tramitação sucessiva outra Comissão) Senador Marcio Bittar (encerrado em 20/03/2019 - (SF-CE) Comissão de Educação, Cultura e Esporte Redistribuição) (SF-CAS) Comissão de Assuntos Sociais Senadora Leila Barros -

Senado Federal Proposta De Emenda À Constituição N° 19, De 2020

SENADO FEDERAL PROPOSTA DE EMENDA À CONSTITUIÇÃO N° 19, DE 2020 Introduz dispositivos ao Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, a fim de tornar coincidentes os mandatos eletivos. AUTORIA: Senador Wellington Fagundes (PL/MT) (1º signatário), Senador Acir Gurgacz (PDT/RO), Senador Alvaro Dias (PODEMOS/PR), Senadora Mailza Gomes (PP/AC), Senadora Maria do Carmo Alves (DEM/SE), Senadora Rose de Freitas (PODEMOS/ES), Senadora Zenaide Maia (PROS/RN), Senador Ciro Nogueira (PP/PI), Senador Confúcio Moura (MDB/RO), Senador Eduardo Gomes (MDB/TO), Senador Elmano Férrer (PODEMOS/PI), Senador Irajá (PSD/TO), Senador Izalci Lucas (PSDB/DF), Senador Jayme Campos (DEM/MT), Senador Luis Carlos Heinze (PP/RS), Senador Major Olimpio (PSL/SP), Senador Marcelo Castro (MDB/PI), Senador Mecias de Jesus (REPUBLICANOS/RR), Senador Nelsinho Trad (PSD/MS), Senador Omar Aziz (PSD/AM), Senador Plínio Valério (PSDB/AM), Senador Rodrigo Pacheco (DEM/MG), Senador Romário (PODEMOS/RJ), Senador Sérgio Petecão (PSD/AC), Senador Telmário Mota (PROS/RR), Senador Weverton (PDT/MA), Senador Zequinha Marinho (PSC/PA) Página da matéria Página 1 de 9 Avulso da PEC 19/2020. SENADO FEDERAL Gabinete Senador Wellington Fagundes PROPOSTA DE EMENDA À CONSTITUIÇÃO Nº , DE 2020 Introduz dispositivos ao Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, a fim de tornar coincidentes os mandatos eletivos. SF/20349.58524-23 As Mesas da Câmara dos Deputados e do Senado Federal, nos termos do § 3º do art. 60 da Constituição Federal, promulgam a seguinte emenda ao texto constitucional: Art. 1º O Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias fica acrescido de artigos, com a seguinte redação: “Art. 115. O mandato dos Prefeitos e dos Vereadores eleitos em 2016 terá a duração de seis anos. -

Senado Federal Parecer (Sf) Nº 28, De 2018

SENADO FEDERAL PARECER (SF) Nº 28, DE 2018 Da COMISSÃO DE ASSUNTOS SOCIAIS, sobre o Projeto de Lei do Senado n°464, de 2012, do Senador Valdir Raupp, que Acrescenta o § 4º no art.53 da Lei 8078 de 11 de setembro de 1990, para considerar abusiva e consequentemente nula cláusula contratual que prevê cobrança de taxa de cadastro em contratos de financiamento, e sobre o Projeto de Lei do Senado n°360, de 2015, do Senador Paulo Paim, que Acrescenta o § 4º ao art. 25 da Lei nº 8.692, de 28 de julho de 1993, que define planos de reajustamento nos contratos de financiamento habitacional no âmbito do Sistema Financeiro da Habitação e dá outras providências, e sobre o Projeto de Lei do Senado n°112, de 2016, do Senador Paulo Paim, que Acrescenta o § 4º ao art. 25 da Lei nº 8.692, de 28 de julho de 1993, que define planos de reajustamento nos contratos de financiamento habitacional no âmbito do Sistema Financeiro da Habitação e dá outras providências. PRESIDENTE: Senadora Marta Suplicy RELATOR: Senador Davi Alcolumbre RELATOR ADHOC: Senador Dalirio Beber 18 de Abril de 2018 2 PARECER Nº , DE 2018 Da COMISSÃO DE ASSUNTOS SOCIAIS (CAS), sobre: o PLS nº 464, de 2012, do Senador Valdir Raupp, que acrescenta o § 4º no art. 53 da Lei nº 8.078 SF/18881.31671-54 de 11 de setembro de 1990, para considerar abusiva e consequentemente nula cláusula contratual que prevê cobrança de taxa de cadastro em contratos de financiamento; o PLS nº 360, de 2015, do Senador Paulo Paim, que acrescenta o § 4º ao art.