King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction In March 1949, when Mao Zedong set out for Beijing from Xibaipo, the remote village where he had lived for the previous ten months, he took along four printed texts. Included were the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian, c. 100 BCE) and the Zizhi tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government, c. 1050 CE), two works that had been studied for centuries by emperors, statesmen, and would-be conquerors. Along with these two historical works, Mao packed two modern Chinese dictionaries, Ciyuan (The Encyclopedic Dictionary, first published by the Commercial Press in 1915) and Cihai (Ocean of Words, issued by Zhonghua Books in 1936- 37).1 If the two former titles, part of the standard repertoire regularly re- printed by both traditional and modern Chinese publishers, are seen as key elements of China’s broadly based millennium-old print culture, then the presence of the two latter works symbolizes the singular intellectual and political importance of two modern industrialized publishing firms. Together with scores of other innovative Shanghai-based printing and publishing enterprises, these two corporations shaped and standardized modern Chi- nese language and thought, both Mao’s and others’, using Western-style printing and publishing operations of the sort commonly traced to Johann Gutenberg.2 As Mao, who had once organized a printing workers’ union, understood, modern printing and publishing were unimaginable without the complex of revolutionary technologies invented by Gutenberg in the fifteenth century. At its most basic level, the Gutenberg revolution involved the adaptation of mechanical processes to the standardization and duplication of texts using movable metal type and the printing press. -

Thema: Das Moderne China Und Die Kategorisierung Seiner Tradition, Eine Rezeption Des Qing-Gelehrten Dai Zhen (1724-1777)

Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg Institut für Kulturwissenschaften Ost- und Südasiens - Sinologie Thesis im Studiengang ‚Modern China‘ Betreuer: Dr. Michael Leibold Datum der Abgabe: 16.08.2011 Thema: Das moderne China und die Kategorisierung seiner Tradition, Eine Rezeption des Qing-Gelehrten Dai Zhen (1724-1777) Name: Immanuel Spaar Adresse: Gneisenaustr. 24 Block E, 97074 Würzburg Geburtsort und –datum: Madison, USA, 05.05.1987 Matrikelnummer: 1620928 Telefon/Mail: 01784938505, [email protected] Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 Ming zu Qing-Übergang und Textkritik-Schule ............................................................ 2 3 Qing-Zeit und die zwei Schulen Hanxue und Songxue ................................................. 6 4 Dai Zhen, Biographie und ausgewählte Werke ............................................................. 9 5 Rezeptionsgeschichte Dai Zhen, Ausgangspunkt 1978 ............................................... 13 5.1 Das Strukturprinzip Li .......................................................................................... 14 5.2 Das Strukturprinzip Li und die Kraftmaterie Qi ................................................... 19 5.3 Der Begriff Dao .................................................................................................... 21 6 Dao-Theorie und normative Ethik, Rezeption aus dem Jahr 2003 .............................. 23 6.1 Erster Abschnitt, -

Read the Introduction

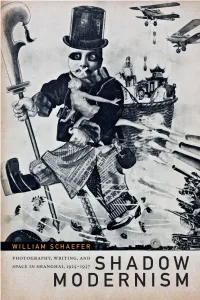

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Fantômes Dans L'extrême-Orient D'hier Et D'aujourd'hui - Tome 2

Fantômes dans l'Extrême-Orient d'hier et d'aujourd'hui - Tome 2 Marie Laureillard et Vincent Durand-Dastès DOI : 10.4000/books.pressesinalco.2679 Éditeur : Presses de l’Inalco Lieu d'édition : Paris Année d'édition : 2017 Date de mise en ligne : 12 décembre 2017 Collection : AsieS ISBN électronique : 9782858312528 http://books.openedition.org Édition imprimée Date de publication : 26 septembre 2017 ISBN : 9782858312504 Nombre de pages : 453 Référence électronique LAUREILLARD, Marie ; DURAND-DASTÈS, Vincent. Fantômes dans l'Extrême-Orient d'hier et d'aujourd'hui - Tome 2. Nouvelle édition [en ligne]. Paris : Presses de l’Inalco, 2017 (généré le 19 décembre 2018). Disponible sur Internet : <http://books.openedition.org/pressesinalco/2679>. ISBN : 9782858312528. DOI : 10.4000/books.pressesinalco.2679. © Presses de l’Inalco, 2017 Creative Commons - Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International - CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 FANTÔMES DANS L’EXTRÊME-ORIENT D’HIER ET D’AUJOURD’HUI TOME 2 Collection AsieS Directeur.trices de collection Catherine Capdeville-Zeng, Matteo De Chiara et Mathieu Guérin Expertise Cet ouvrage a été évalué en double aveugle Correction et préparation de copie François Fièvre Enrichissements sémantiques Huguette Rigot Fabrication Nathalie Bretzner Maquette intérieure Nathalie Bretzner Maquette couverture Nathalie Bretzner Illustration couverture Image extraite de l’album Guiqu tu 鬼趣圖 (Plaisirs spectraux) par Pu Xinyu 溥心畬, 1896-1963. Collection privée, tous droits réservés. Licence CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 Difusion électronique https://pressesinalco.fr Cet ouvrage a été réalisé par les Presses de l’Inalco sur Indesign avec Métopes, méthodes et outils pour l’édition structurée XML-TEI développés par le pôle Document numérique de la MRSH de Caen. -

Indian Images in Chinese Literature: a Historical Survey

Indian Images in Chinese Literature: A Historical Survey Tan Chung School of Languages Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi. INDIA is the closest ancient civilization to China which is another ancient civilization. The two civilizations can be described as ’Trans-Himalayan Twins’ not only because they rank the Himalayan ranges, but also because both were given birth to by the rivers flowing from the Himalayan region. It is but natural that India figures prominently in the Chinese imagination, folklore, and literary records. The image of India in Chinese literature changes according to two factors: (i) mutual knowledge and intimacy between Indian and Chinese peoples, and (ii) India’s impact on China. We can divide the cultural contacts between India and China into four historical periods. First, from the time of Christ to the early centuries of the present millennium was the period when China was under active influence of Indian culture through the vehicle of Buddhism. Second, from the 13th to the 19th century was a period of little contact between India and China. In the meanwhile, both countries underwent political, social and cultural changes because of invasions by external forces. Third, from the 19th century upto the time when both countries won complete independence from West- ern imperialist domination (India in 1947 and China in 1949) was the period when the two trans-Himalayan twins became colonial twins-co-sufferers of the world imperialist systems. From the 1950s onwards, we have the fourth period of Sino-Indian contacts which saw the two newly independent peoples first being perplexed by the historical burdens and recently starting the process of liberating themselves from the labyrinth of historical problems 51 Downloaded from chr.sagepub.com at Sciences Po on September 27, 2016 to found Sino-Indian relations on a new rational basis. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction k dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversee materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WU CHANGSHI AND THE SHANGHAI ART WORLD IN THE LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Kuiyi Shen, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John C. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9 ’ black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 North ZaeD Road. -

CANTONESE LOVE SONGS (YUE OU粵謳) PREFACE TWO1 Translated with an Introduction by LITONG CHEN and NICHOLAS JOCH

Asian Literature and Translation Vol. 3, No. 2 (2015) 1-15 CANTONESE LOVE SONGS (YUE OU粵謳) PREFACE TWO1 Translated with an Introduction by LITONG CHEN and NICHOLAS JOCH Introduction The term “Yue ou” 粵謳 (alternatively Yueh eo) has at least three different yet mutually-related meanings. First, the term refers to a traditional form of folk songs sung in the Pearl River Delta region, Guangdong, for hundreds of years. The authors of the songs are usually unknown; a single song may have several variations, in terms of both the tune and the lyrics. Additionally, Yue ou can indicate a genre of songs, the lyrics of which were composed by Cantonese poets (most of whom were also experts in music) in the 19th century. The tunes were edited on the basis of traditional folk songs. In the current project, Yue ou takes a third meaning, i.e., the name of a particular songbook, composed of 97 folk songs. The songbook was written by Zhao Ziyong 招子庸 (alternatively Chao Tzu-yung, Jiu Ji-yung), one of the few folk song writers whose name and identity are known (together with Feng Xun 馮詢 and Qiu Mengqi 邱夢旗, as Xian (1947) mentions). Zhao was born in 1795 (the 60th year of Emperor Qianlong’s乾隆 reign) in Nanhai 南 海, Guangdong, and died in 1846 (the 26th year of Emperor Daoguang’s道光 reign). His courtesy name was Mingshan 銘山, his literary name being Layman Mingshan 明珊居士. The songbook Yue ou is probably the second earliest extant colloquial Cantonese document.2 The collection is important not only as a reflection of everyday life in 19th-century Guangdong, but also as a profoundly authentic snapshot of spoken Cantonese, which is usually written with a mixture of standard Chinese characters and a number of additional characters created specifically for Cantonese. -

Thomas Creamer

Thomas Creamer RECENT AND FORTHCOMING CHINESE-ENGLISH AND ENGLISH-CHINESE DICTIONARIES FROM THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Introduction Lexicography in China has had a long and interesting history. The first known Chinese dictionary, SHI ZHOU PIAN, was compiled during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.); the first Chinese bilingual dictionary, HUA YI CIDIAN, was published in the early 1400s by a government bureau established to study things foreign. Many of the early bilingual dictionaries dealt with tech nical subjects.l Chinese-English and English-Chinese dictionaries began to appear in the 1800s as Christian missionaries and foreign traders settled in China. There have been a number of bilingual dic tionaries early this century, by such compilers as Giles, Mathews and Zheng, but with the profound changes in the Chinese and English languages, most are now obsolete. In recent years lexicographers in the People's Republic of China have published numerous Chinese and English dictionaries that are far superior to any works in the past. This paper surveys recent and forthcoming bilingual works, including HAN YING CIDIAN, XIAO HAN YING CIDIAN, XIN YING HAN CIDIAN, YING HAN DA CIDIAN, and XIN YING HAN XUESHENG CIDIAN (full references are given in the Bibliography of cited dictionaries at the end of this volume). Selection of entries The selection of entries in a dictionary with Chinese as the source language is a difficult process for two reasons. First, due to the structure of the Chinese language, there is no consensus as to what constitutes a word.2- Second, until the appearance in 1978 of XIANDAI HANYU CIDIAN (A DICTIONARY OF CONTEMPORARY CHINESE, here after XIAN HAN), no authoritative monolingual dictionary of the everyday Chinese language existed. -

Kapitel 4 - Schlußbetrachtung

191 Kapitel 4 - Schlußbetrachtung Im folgenden und letzten Abschnitt dieser Studie zu den shanzhi will ich einen Brückenschlag versuchen, der mehreres vereint. Es steht das Material der SZ als Ganzes und in seinen sezierten Teilen zu Verfügung, und man kann nun den viel- fältigsten (seichten und tieferen) Fragestellungen nachgehen. So könnte man, gerüstet mit allerlei wissenschaftlichem Instrumentarium, darangehen zu prüfen, ob die sehr spät erfolgende Entwicklung einer aufklärerisch argumentierenden chinesischen Na- turanschauung tatsächlich nur in der Abtrennung von religiöser “Wahrheit” er- möglicht wurde oder doch vielmehr deren letztgültige und trotzdem unfertige Verma- chenschaft war.1 Eine weitere Möglichkeit, das Material zu befragen, besteht darin, die ungemein großzügig mit allen erdenklichen Attributen angereicherten Berge Chinas als Beispiele für einen konstruierten, hochgradig verdichteten und artifiziellen Raum (sie sind nicht konstruierte Natur!) aufzufassen, um sie auf der Ebene der Abstraktion in einen methodischen Diskurs mit westlichen Vorstellungen von Raum und seiner Organisation zu stellen. Dieser zweite Weg soll hier diskutiert werden. Dabei wird nicht allzuweit auszuholen sein, da uns mit den Arbeiten von Lefebvre2, Koyré, Sopher3, Jammer, Bollnow, Blumenberg und deren synthetisierenden Nach- fahren exzellente, nachgerade auch sehr unterschiedliche, aber doch ungemein be- 1 Vgl. dazu Kubin 1985, op. cit., S.329 f. Eine “Vermenschlichung von Natur”, wie Kubin auf S. 331 erst für die Song-Zeit reklamiert, scheint mir übrigens schon früher gegeben. Die Anthropomorphisierung bestimmter Naturräume ist eines der ältesten Mittel der Menschheit, der “Angst” (S. 330) Herr zu werden, ohne unkontrollierbaren Naturmächten anheimzufallen. 2 Henri Lefebvre (Jahrgang 1901) gilt als “one of the great French intellectual activists of the twentieth century” (so das Nachwort von David Harvey zum hiernach zitierten Hauptwerk Lefebvres: “The Production of Space”, S. -

Produzent Adresse Land

Produzent Adresse Land Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Dos Ideogramas (China) Às Palavras (Brasil) : Elaboração Do Primeiro Dicionário Básico Bilíngüe Português-Chinês

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA, PORTUGUÊS E LÍNGUAS CLÁSSICAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LINGÜÍSTICA DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO DOS IDEOGRAMAS (CHINA) ÀS PALAVRAS (BRASIL) : ELABORAÇÃO DO PRIMEIRO DICIONÁRIO BÁSICO BILÍNGÜE PORTUGUÊS-CHINÊS Luo Yan Julho de 2007 Brasília – DF LUO YAN DOS IDEOGRAMAS (CHINA) ÀS PALAVRAS (BRASIL) : ELABORAÇÃO DO PRIMEIRO DICIONÁRIO BÁSICO BILÍNGÜE PORTUGUÊS-CHINÊS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu do Departamento de Lingüística, Português e Línguas Clássicas da Universidade de Brasília – UnB, como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Lingüística. Orientadora: Profa. Doutora Enilde Faulstich Brasília – DF Julho de 2007 BANCA EXAMINADORA Profª. Dra. Enilde Faulstich ( LIP ) - UnB Presidente ________________________________________ Prof ª. Dra Patrícia Vieira Nunes Gomes (Michellangelo) Membro efetivo ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Li Weigang ( CIC ) - UnB Membro efetivo ________________________________________ Prof. Dr. René Strehler (LET) - UnB Membro suplente ________________________________________ AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de registrar o meu reconhecimento àqueles que contribuíram para a realização deste trabalho: Aos meus pais, pelo amor que me dedicam, pela compreensão e pelo suporte emocional e espiritual. À Professora Dra. Enilde Faulstich, pela acolhida de meu projeto de mestrado e por sua precisa orientação. À minha amiga Thaís Lobos, por sua sempre disponibilidade e grande generosidade em transmitir seus conhecimentos em relação à língua portuguesa. À amiga Liu Jia que é formada na Língua e Literatura Chinesa, pela ajuda na coleta dos dados da língua chinesa e sanar muitas dúvidas sobre a língua. Ao Professor Zhang Jianbo do Departamento da Língua Espanhola e Portuguesa da Universidade dos Estudos Estrangeiros de Beijing pela avaliação e sugestões na elaboração do dicionário que aqui apresento.