Thomas Creamer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Audio Content for Re-Listening

European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences EpSBS www.europeanproceedings.com e-ISSN: 2357-1330 DOI: 10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.03.23 DCCD 2020 Dialogue of Cultures - Culture of Dialogue: from Conflicting to Understanding INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN TEACHING CHINESE: ANALYSIS AND CLASSIFICATION OF DIGITAL EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Tatiana L. Guruleva (a)* *Corresponding author (a) Moscow City University, 5B Malyj Kazennyj pereulok, Moscow, Russia; Institute of Far Eastern Studies of Russian Academy of Sciences, 32 Nakhimovskii prospect, 117997, Moscow, Russia, [email protected] Abstract The intercultural approach to teaching Chinese as a foreign language in Russia was first implemented by us in a model for co-learning languages and cultures. This model was developed in 2009-2011, it took into account the specifics of teaching the Chinese language, which is studied simultaneously with the English language. The model was tested in the international multicultural educational region of Siberia and the Far East of Russia and northeastern part of China. However, the intercultural approach has wide potential for implementation not only in conditions of direct contact with representatives of another culture. In the modern world, information technologies for teaching foreign languages are increasingly in demand. For a number of objective reasons, large technology companies until the beginning of the 21st century could not begin to develop information technologies that support the Chinese language. Therefore, the history of the creation and use of information technologies for teaching the Chinese language is happening right now before our eyes. In this regard, the analysis and classification of information resources for teaching the Chinese language is relevant and in demand. -

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3196R2 1. Summary

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3196R2 Page 1 of 10 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3196R2 Title Proposal to Disunify U+4039 Source Andrew West and John Jenkins Document Type Expert Contribution Date 2007-05-01 1. Summary 䀹 目 夾 The character U+4039 is a unification of two different glyphs, one written as (i.e. mù radical and ji 䀹 目 㚒 phonetic) and one written as (i.e. mù radical and sh n phonetic). It is the former of these two glyph forms that is used to represent this character in the Unicode code charts and in most CJK fonts. The glyph form of U+4039 in various sources are shown below : ISO/IEC 10646:2003 page 307 Super CJK Version 14.0 page 1049 The Unicode Standard 5.0 code charts page 301 JIS X 0213:2000 Plane 2 Row 82 Col.2 (J4-7222) ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3196R2 Page 2 of 10 Ѝ There is also a simplified form of the ji phonetic glyp䀹h (U+25174 ), aᴔs well as two compatability ideographs that are canonically equivalent to U+4039 : U+FAD4 and U+2F949 . The situation is summarised in the table below : Source References Code Point Character (from ISO/IEC 10646:2003 Amd.1) G3-5952 T4-3946 4039 䀹 J4-7222 H-98E6 KP1-5E34 FAD4 䀹 KP1-5E2B 25174 Ѝ G_HZ 2F949 ᴔ T6-4B7A 䀹 䀹 We believe that the two glyph forms of U+4039 ( and ) are non-cognate, and so, according to the rules for CJK unification (see ISO/IEC 10646:2003 Annex S, S.1.1), should not have been unified. -

Introduction

Introduction In March 1949, when Mao Zedong set out for Beijing from Xibaipo, the remote village where he had lived for the previous ten months, he took along four printed texts. Included were the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian, c. 100 BCE) and the Zizhi tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government, c. 1050 CE), two works that had been studied for centuries by emperors, statesmen, and would-be conquerors. Along with these two historical works, Mao packed two modern Chinese dictionaries, Ciyuan (The Encyclopedic Dictionary, first published by the Commercial Press in 1915) and Cihai (Ocean of Words, issued by Zhonghua Books in 1936- 37).1 If the two former titles, part of the standard repertoire regularly re- printed by both traditional and modern Chinese publishers, are seen as key elements of China’s broadly based millennium-old print culture, then the presence of the two latter works symbolizes the singular intellectual and political importance of two modern industrialized publishing firms. Together with scores of other innovative Shanghai-based printing and publishing enterprises, these two corporations shaped and standardized modern Chi- nese language and thought, both Mao’s and others’, using Western-style printing and publishing operations of the sort commonly traced to Johann Gutenberg.2 As Mao, who had once organized a printing workers’ union, understood, modern printing and publishing were unimaginable without the complex of revolutionary technologies invented by Gutenberg in the fifteenth century. At its most basic level, the Gutenberg revolution involved the adaptation of mechanical processes to the standardization and duplication of texts using movable metal type and the printing press. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:34:09AM Via Free Access Bruce Rusk: Old Scripts, New Actors 69

EASTM 26 (2007): 68-116 Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700* Bruce Rusk [Bruce Rusk is Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. From 2004 to 2006 he was Mellon Humani- ties Fellow in the Asian Languages Department at Stanford University. His dis- sertation was entitled “The Rogue Classicist: Feng Fang and his Forgeries” (UCLA, 2004) and his article “Not Written in Stone: Ming Readers of the Great Learning and the Impact of Forgery” appeared in The Harvard Journal of Asi- atic Studies 66.1 (June 2006).] * * * But if a savage or a moon-man came And found a page, a furrowed runic field, And curiously studied line and frame: How strange would be the world that they revealed. A magic gallery of oddities. He would see A and B as man and beast, As moving tongues or arms or legs or eyes, Now slow, now rushing, all constraint released, Like prints of ravens’ feet upon the snow. — Herman Hesse1 Visitors to the Far East from early modern Europe reported many marvels, among them a writing system unlike any familiar alphabetic script. That the in- habitants of Cathay “in a single character make several letters that comprise one * My thanks to all those who provided feedback on previous versions of this paper, especially the workshop commentator, Anthony Grafton, and Liam Brockey, Benjamin Elman, and Martin Heijdra as well as to the Humanities Fellows at Stanford. I thank the two anonymous readers, whose thoughtful comments were invaluable in the revision of this essay. -

Homophone Density and Word Length in Chinese 1. the Issue

[Type text] [Type text] [Type text] Homophone Density and Word Length in Chinese San Duanmu and Yan Dong Abstract Chinese has many disyllabic words, such as 煤炭 meitan ‘coal’, 老虎 laohu ‘tiger’, and 学习 xuexi ‘study’, most of which can be monosyllabic, too, such as 煤 mei ‘coal’, 虎 hu ‘tiger’, and 学 xue ‘study’. A popular explanation for such length pairs is homophone avoidance, where disyllabic forms are created to avoid homophony among monosyllables. In this study we offer a critical review of arguments for the popular view, which often rely on cross-linguistic comparisons. Then we offer a quantitative analysis of word length pairs in the Chinese lexicon in order to find out whether there is internal evidence for a correlation between homophony and word length. Our study finds no evidence for the correlation. Instead, the percentage of disyllabic words is fairly constant across all degrees of homophony. Our study calls for a reconsideration of the popular view. Alternative explanations are briefly discussed. 1. The issue: elastic word length in Chinese Chinese has many synonymous pairs of word forms, one short and one long. The short one is monosyllabic and the long one is made of the short one plus another morpheme. Since the long form has the same meaning as the short (evidenced by their mutual annotation in the dictionary), the meaning of its extra morpheme is either redundant or lost. Some examples are shown in (1), where Chinese data are transcribed in Pinyin spelling (tones are omitted unless relevant). In each case, the extra part of the long form is shown in parentheses. -

Multimedia Systems Engineering

Dictionaries and ideology: examples from The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (Xiandai hanyu cidian 现代汉语词典) Chiara Bertulessi Università degli Studi di Milano Email: [email protected] Abstract: Any dictionary-making process involves choices about the selection of words that can be included in (or excluded from) the list of entries as well as about the nature of their definitions (Crowley 2005: 138). As Fishman pointed out (1995: 29), dictionaries are cultural artifacts and, as such, they always tell us something about the characteristics of their compilers, of their intended users as well as of the society and culture to which they belong. In this sense, dictionaries can also be seen from an ideological perspective, i.e. by considering them as potential means of expressions of the dominant ideology (Fairclough 1989) of the specific political, social and cultural context in which the compilation has occurred. The paper discusses the results of a case study conducted on different editions of The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (Xiandai hanyu cidian 现代汉语词典), one of the most authoritative monolingual Chinese dictionaries, which is compiled by the Institute of Linguistics of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. By presenting the analysis of selected entries and definitions, the paper aims at examining if, and to what extent, the several ideological shifts The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary has gone through (Lee 2014: 429) reflect the ideological, political, social and cultural changes that have taken place in the People’s Republic of China during the nearly forty years of its publication (1978 – 2016). References Crowley, T. (2005). Encoding Ireland: Dictionaries and Politics in Irish History. -

Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700 *

EASTM 26 (2007): 68-116 Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700 * Bruce Rusk [Bruce Rusk is Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. From 2004 to 2006 he was Mellon Humani- ties Fellow in the Asian Languages Department at Stanford University. His dis- sertation was entitled “The Rogue Classicist: Feng Fang and his Forgeries” (UCLA, 2004) and his article “Not Written in Stone: Ming Readers of the Great Learning and the Impact of Forgery” appeared in The Harvard Journal of Asi- atic Studies 66.1 (June 2006).] * * * But if a savage or a moon-man came And found a page, a furrowed runic field, And curiously studied line and frame: How strange would be the world that they revealed. A magic gallery of oddities. He would see A and B as man and beast, As moving tongues or arms or legs or eyes, Now slow, now rushing, all constraint released, Like prints of ravens’ feet upon the snow. — Herman Hesse 1 Visitors to the Far East from early modern Europe reported many marvels, among them a writing system unlike any familiar alphabetic script. That the in- habitants of Cathay “in a single character make several letters that comprise one * My thanks to all those who provided feedback on previous versions of this paper, especially the workshop commentator, Anthony Grafton, and Liam Brockey, Benjamin Elman, and Martin Heijdra as well as to the Humanities Fellows at Stanford. I thank the two anonymous readers, whose thoughtful comments were invaluable in the revision of this essay. -

Thema: Das Moderne China Und Die Kategorisierung Seiner Tradition, Eine Rezeption Des Qing-Gelehrten Dai Zhen (1724-1777)

Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg Institut für Kulturwissenschaften Ost- und Südasiens - Sinologie Thesis im Studiengang ‚Modern China‘ Betreuer: Dr. Michael Leibold Datum der Abgabe: 16.08.2011 Thema: Das moderne China und die Kategorisierung seiner Tradition, Eine Rezeption des Qing-Gelehrten Dai Zhen (1724-1777) Name: Immanuel Spaar Adresse: Gneisenaustr. 24 Block E, 97074 Würzburg Geburtsort und –datum: Madison, USA, 05.05.1987 Matrikelnummer: 1620928 Telefon/Mail: 01784938505, [email protected] Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 Ming zu Qing-Übergang und Textkritik-Schule ............................................................ 2 3 Qing-Zeit und die zwei Schulen Hanxue und Songxue ................................................. 6 4 Dai Zhen, Biographie und ausgewählte Werke ............................................................. 9 5 Rezeptionsgeschichte Dai Zhen, Ausgangspunkt 1978 ............................................... 13 5.1 Das Strukturprinzip Li .......................................................................................... 14 5.2 Das Strukturprinzip Li und die Kraftmaterie Qi ................................................... 19 5.3 Der Begriff Dao .................................................................................................... 21 6 Dao-Theorie und normative Ethik, Rezeption aus dem Jahr 2003 .............................. 23 6.1 Erster Abschnitt, -

1 LUNDS UNIVERSITET Institutionen För Kinesiska

LUNDS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för kinesiska "道生一,一生二,二生三,三生万物" (Laozi) [Vägen frambringar en, en frambringar två, två frambringar tre, tre frambringar myriad av varelser] - En översikt av utvecklingshistoria på kinesiskans ordförråd ur ordlängdens och ordkonstruktionens perspektiv Fen Han [email protected] 1 Innehållsförteckning 1 Sammanfattning 2 1. Inledning 3 1.1 Bakgrund 3 1.2 Frågeställning 3 1.3 Något om begrepp 3 2. Theorier om ordkonstruktion 5 2.1 Forskningsteorier runt ordkonstruktion 5 2.1.1 Kring den traditionella typen 5 2.1.2 Kring den anti-traditionella typen 5 2.1.3 Kring den mångsidiga typen 6 2.2 Den klassiska grupperingen av kinesiska ord ur ett konstruktionsperspektiv 6 2.2.1 Isolerade ord 6 2.2.2 Komplexa ord 7 2.3 Konstruktionsprinciper för komplexa ord 8 2.3.1 Repetition 8 2.3.2 Affixation 9 2.3.3 Sammansättning 11 2.3.3.1 Parallella principen 11 2.3.3.2 Attributiva principen 14 2.3.3.3 Komplementiva principen 15 2.3.3.4 Verb-objektiv principen 17 2.3.3.5 Subjekt-predikativ principen 18 2.3.4 Multipel principen 18 3. Den tvåstaviga tendensen i utvecklingshistoria av kinesiskans ordlängder 20 3.1 Kortfattad utvecklingshistoria av kinesiskans ordlängder och den tvåstaviga tendensen 20 3.1.1 Enstaviga ord 20 3.1.2 Tvåstaviga ord 20 3.1.3 Flerstaviga ord 23 3.2 Den tvåstaviga tendensen i språkutvecklingen 24 3.3 Anledningar bakom den tvåstaviga tendensen 26 3.3.1 Kommunikationsbehov 27 3.3.2 Uttrycksbehov 27 3.3.3 Estetiskt behov 28 3.4 Användning av ordkonstruktionsprinciperna under historien och i nu tid 29 3.3.1 De mest produktiva ordkonstruktionsprinciperna under historien 29 3.3.2 Enstaviga ord och tvåstaviga ord i modern kinesiska, mer eller mindre? 30 4. -

Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary Free

FREECONCISE ENGLISH-CHINESE CHINESE-ENGLISH DICTIONARY EBOOK Manser H. Martin | 696 pages | 01 Jan 2011 | Commercial Press,The,China | 9787100059459 | English, Chinese | China Excerpt from A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers | Penguin Random House Canada Notable Chinese dictionariespast and present, include:. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikipedia list article. Dictionaries of Chinese. List of Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary dictionaries. Categories : Chinese dictionaries Lists of reference books. Concise English- Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary categories: Articles with short description Short description is different from Wikidata. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Add links. First Chinese dictionary collated in single-sort alphabetical order of pinyin, John DeFrancis. A Chinese-English Dictionary. Herbert Allen Giles ' bestselling dictionary, 2nd ed. A Dictionary of the Chinese Language. A Syllabic Dictionary of the Chinese Language. Small Seal Script orthographic primer, Li Si 's language reform. Chinese Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary English Dictionary. Popular modern general-purpose encyclopedic dictionary, 6 editions. Concise Dictionary of Spoken Chinese. Tetsuji Morohashi 's Chinese- Japanese character dictionary, 50, entries. Oldest extant Chinese dictionary, semantic field collationone of the Thirteen Classics. Yang Xiongfirst dictionary of Chinese regional varieties. Le Grand Ricci or Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise,". First orthography dictionary of the regular script. Grammata Serica Recensa. Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects. Compendium of dictionaries for 42 local varieties of Chinese. Zhang Yi 's supplement to the Erya. Rime dictionary expansion of Qieyunsource for reconstruction of Middle Chinese. -

Read the Introduction

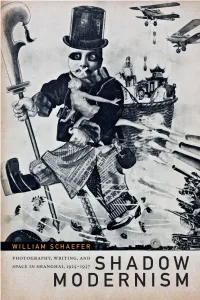

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Fantômes Dans L'extrême-Orient D'hier Et D'aujourd'hui - Tome 2

Fantômes dans l'Extrême-Orient d'hier et d'aujourd'hui - Tome 2 Marie Laureillard et Vincent Durand-Dastès DOI : 10.4000/books.pressesinalco.2679 Éditeur : Presses de l’Inalco Lieu d'édition : Paris Année d'édition : 2017 Date de mise en ligne : 12 décembre 2017 Collection : AsieS ISBN électronique : 9782858312528 http://books.openedition.org Édition imprimée Date de publication : 26 septembre 2017 ISBN : 9782858312504 Nombre de pages : 453 Référence électronique LAUREILLARD, Marie ; DURAND-DASTÈS, Vincent. Fantômes dans l'Extrême-Orient d'hier et d'aujourd'hui - Tome 2. Nouvelle édition [en ligne]. Paris : Presses de l’Inalco, 2017 (généré le 19 décembre 2018). Disponible sur Internet : <http://books.openedition.org/pressesinalco/2679>. ISBN : 9782858312528. DOI : 10.4000/books.pressesinalco.2679. © Presses de l’Inalco, 2017 Creative Commons - Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International - CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 FANTÔMES DANS L’EXTRÊME-ORIENT D’HIER ET D’AUJOURD’HUI TOME 2 Collection AsieS Directeur.trices de collection Catherine Capdeville-Zeng, Matteo De Chiara et Mathieu Guérin Expertise Cet ouvrage a été évalué en double aveugle Correction et préparation de copie François Fièvre Enrichissements sémantiques Huguette Rigot Fabrication Nathalie Bretzner Maquette intérieure Nathalie Bretzner Maquette couverture Nathalie Bretzner Illustration couverture Image extraite de l’album Guiqu tu 鬼趣圖 (Plaisirs spectraux) par Pu Xinyu 溥心畬, 1896-1963. Collection privée, tous droits réservés. Licence CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 Difusion électronique https://pressesinalco.fr Cet ouvrage a été réalisé par les Presses de l’Inalco sur Indesign avec Métopes, méthodes et outils pour l’édition structurée XML-TEI développés par le pôle Document numérique de la MRSH de Caen.