ICOMOS: PERU — CHAVIN DE HUANTAR Monitoring and Follow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

159. City of Cusco, Including Qorikancha (Inka Main Temple), Santa Domingo (Spanish Colonial Convent), and Walls of Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman)

159. City of Cusco, including Qorikancha (INka main temple), Santa Domingo (Spanish colonial convent), and Walls of Saqsa Waman (Sacsayhuaman). Central highlands, Peru. Inka. C.1440 C.E.; conent added 1550-1650 C.E. Andesite (3 images) Article at Khan Academy Cusco, a city in the Peruvian Andes, was once capital of the Inca empire, and is now known for its archaeological remains and Spanish colonial architecture. Set at an altitude of 3,400m, it's the gateway to further Inca sites in the Urubamba (Sacred) Valley and the Inca Trail, a multiday trek that ends at the mountain citadel of Machu Picchu. Carbon-14 dating of Saksaywaman, the walled complex outside Cusco, has established that the Killke culture constructed the fortress about 1100 o The Inca later expanded and occupied the complex in the 13th century and after Function: 2008, archaeologists discovered the ruins of an ancient temple, roadway and aqueduct system at Saksaywaman.[11] The temple covers some 2,700 square feet (250 square meters) and contains 11 rooms thought to have held idols and mummies,[11] establishing its religious purpose. Together with the results of excavations in 2007, when another temple was found at the edge of the fortress, indicates there was longtime religious as well as military use of the facility, overturning previous conclusions about the site. Many believe that the city was planned as an effigy in the shape of a puma, a sacred animal. It is unknown how Cusco was specifically built, or how its large stones were quarried and transported to the site. -

Southern Destinations Gihan Tubbeh Renzo Giraldo Renzo Gihan Tubbeh Gihan Tubbeh

7/15/13 8:18 PM 8:18 7/15/13 1 Sur.indd EN_07_Infografia As you head south, you start to see more of Peru’s many different facets; in terms of our ancient cultural legacy, the most striking examples are the grand ruins Ancient Traditions Ancient History Abundant Nature There are plenty of southern villages that still Heading south, you are going to find vestiges of Machu Picchu and road system left by the Incan Empire and the mysterious Nasca Lines. As keep their ancestors’ life styles and traditions Uros Island some of Peru’s most important Pre-Colombian Peru possesses eighty-four of the existing 104 life zones for natural seings, our protected areas and coastal, mountain, and jungle alive. For example, in the area around Lake civilizations. Titicaca, Puno, the Pukara thrived from 1800 Also, it is the first habitat in the world for buerfly, fish and orchid species, second in bird species, and B.C. to 400 A.D., and their decline opened up landscapes offer plenty of chances to reconnect with nature, even while engaging Ica is where you find the Nasca Lines, geoglyphs third in mammal and amphibian species. the development of important cultures like of geometric figures and shapes of animals and in adventure sports in deserts (dunes), beaches, and rivers. And contemporary life the Tiahuanaco and Uro. From 1100 A.D. to the plants on the desert floor that were made 1500 arrival of the Spanish, the Aymara controlled is found in our main cities with their range of excellent hospitality services offered years ago by the Nasca people. -

Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography

arts Article Inverted Worlds, Nocturnal States and Flying Mammals: Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography Aleksa K. Alaica Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Bats are depicted in various types of media in Central and South America. The Moche of northern Peru portrayed bats in many figurative ceramic vessels in association with themes of sacrifice, elite status and agricultural fertility. Osseous remains of bats in Moche ceremonial and domestic contexts are rare yet their various representations in visual media highlight Moche fascination with their corporeal form, behaviour and symbolic meaning. By exploring bat imagery in Moche iconography, I argue that the bat formed an important part of Moche categorical schemes of the non-human world. The bat symbolized death and renewal not only for the human body but also for agriculture, society and the cosmos. I contrast folk taxonomies and symbolic classification to interpret the relational role of various species of chiropterans to argue that the nocturnal behaviour of the bat and its symbolic association with the moon and the darkness of the underworld was not a negative sphere to be feared or rejected. Instead, like the representative priestesses of the Late Moche period, bats formed part of a visual repertoire to depict the cycles of destruction and renewal that permitted the cosmological continuation of life within North Coast Moche society. Keywords: bats; non-human animals; Moche; moon imagery; priestess; sacrifice; agriculture; fertility 1. -

Community Focused Integration & Protected

COMMUNITY FOCUSED INTEGRATION & PROTECTED AREAS MANAGEMENT IN THE HUASCARÁN BIOSPHERE RESERVE, PERÚ October 2015 | Jessica Gilbert In Summer 2015, ConDev Student Media Grant winner Jessica Gilbert conducted a photojournalism and film project to document land use issues and a variety of stakeholder perspectives in protected areas in Peru. Peru’s natural protected areas are threatened by a host of anthropogenic activities, which lead to additional conflicts with nearby communities. The core of this project involved a trip to Peru in May 2015 to highlight land use challenges in two distinct protected areas: Huascarán National Park and Tambopata National Reserve. In this contribution to the Applied Biodiversity Science Perspectives Series (http://biodiversity.tamu.edu/communications/perspectives-series/), Gilbert discusses the integration of communities into conservation management and criticizes the traditional “fortress”-style conservation policies, which she argues are incompatible with ecosystem conservation. Jessica Gilbert is a Ph.D. student in Texas A&M The Center on Conflict and Development University’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (ConDev) at Texas A&M University seeks to improve Sciences as well as a member of the NSF-IGERT the effectiveness of development programs and policies Applied Biodiversity Sciences Program. for conflict-affected and fragile countries through multidisciplinary research, education and development extension. The Center uses science and technology to reduce armed conflict, sustain families and communities during conflict, and assist states to rapidly recover from conflict. ConDev’s Student Media Grant, funded by the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, awards students with up to $5,000 to chronicle issues facing fragile and conflict- affected nations through innovative media. -

Evidencia Del Complejo Arqueológico Kuélap

El efecto de la inversion´ en infraestructura sobre la demanda tur´ıstica: evidencia del complejo arqueologico´ kuelap.´ Erick Lahura, Lucely Puscan y Rosario Sabrera* Resumen ¿Cu´ales el efecto de la inversi´onen infraestructura sobre la demanda tur´ıstica? Para responder a esta pregunta, se analiza el caso del Complejo Arqueol´ogico Ku´elap,el cual se ha beneficiado de la construcci´onde un sistema de telecabinas que ha hecho m´asaccesible y atractiva su visita desde su inauguraci´onen marzo del a~no2017. La hip´otesisque se plantea es que dicha inversi´onen infraestructura tur´ıstica ha tenido un efecto importante sobre la demanda tur´ıstica de Ku´elap.Para evaluar la validez de esta hip´otesis,se aplica un estudio de caso comparativo en el cual se utiliza un \control sint´etico" construido a partir de la informaci´onde los diferentes sitios arqueol´ogicos del Per´uentre los a~nos2008 y 2018. Este control sint´etico permite estimar cu´alhubiera sido la evoluci´onde las visitas a Ku´elapsi no se hubiera construido el sistema de telecabinas. Los resultados muestran que la inversi´onen infraestructura tur´ıstica en Ku´elapgener´oun aumento de aproximadamente 100 por ciento en el n´umero de visitas. En los ´ultimosa~nos,el turismo ha incrementado su importancia dentro de la econom´ıa,especialmente en pa´ısesen desarrollo Faber y Gaubert (2019). Seg´unla Organizaci´onMundial del Turismo (2019), dicha actividad genera cerca del 10 % del PBI mundial y crea 1 de cada 10 empleos en el mundo. En el Per´u,el turismo ha logrado una contribuci´onde cerca del 4 % al PBI nacional, seg´unreporta el Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo (2016). -

Universidad Nacional Del Callao

ACADEMIA AUGE HISTORIA DEL PERú Y UNIVERSAL http://www.academiaauge.com CUESTIONARIO DESARROLLADO ACADEMIA AUGE HISTORIA DEL PERú Y UNIVERSAL INTRODUCCIÓN El hombre llegó a América después de un largo proceso migratorio que parte desde el África y culmina en nuestro continente. Para subsistir, el hombre recurrió a actividades elementales, tales como la recolección, pesca y cacería; evidenciándose de esta manera, la primera contradicción del hombre contra la naturaleza, que corresponde a la primera etapa de la historia de la humanidad. Así, “los primeros grupos de homínidos que llegaron a América vinieron, pues, soportando la dramática lucha entre el hombre y la bestia, entre lo nuevo y lo viejo” (Emilio Choy 1987). Los hombres migran de un lugar a otro buscando territorios donde asentarse para poder aprovechar los recursos y así lograr la satisfacción de sus necesidades. Las primeras huellas de poblamiento americano lo encontramos en los yacimientos arqueológicos de Clovis y Folson (Canada y EE.UU.), cuyas artefactos líticos datan de aproximadamente 60,000 años; Entre otras evidencias tenemos: • Dawson City: Canadá 40 000 a.C. • Lewisville: EE.UU 38,000 a.C. • Old Crow: Alaska 27,000 a.C. • Tlapacoya: México 24 000 a.C. • El Bosque: Nicaragua 22,000 a.C. • Paccaicasa: Perú 20,000 a.C. • Punín: Ecuador 12,000 a.C. • Viscachani: Bolivia 8,000 a.C. IMPORTANTE: El Fósil más antiguo de América es el CRÁNEO DE LOS ANGELES, con un antigüedad de 21,000 a.C. La era Cuaternaria (2’000000 – hasta la actualidad), se divide en dos grandes Periodos: el PLEISTOCENO Y EL HOLOCENO. -

Andean Path to Machu Picchu

ADVENTURE PROGRAM: APURIMAC RIVER: Head Water of the Amazon River + MACHU PICCHU “” DAY BY DAY ITINERARY DAY 1: ARRIVE TO CUSCO At your arrival to Cusco Airport our representative will be waiting for you to take you you hotel located at center of the City. Overnight at Cusco City No meals Included DAY 2: CUSCO We will pick you up from your hotel or meet you at the place of your choice for the city tour. We will start with a visit to the Cathedral, built over 450 years ago, and its fine collection of paintings of the Cusqueño School. After this, we will visit the Koricancha, the most sumptuous temple of the Inca culture, which was dedicated to worship the sun. Next, we will drive to the magnificent ruins of Sacsayhuaman and its impressive rocky constructions, followed by Kenko, PukaPukara and Tambomachay. Finally, we will head back to Cusco city. Overnight at Cusco City MEAL: Breakfast + Lunch Email Alberto: [email protected] Call Alberto: +51 9417 012 16. www.apumayo.com DAY BY DAY ITINERARY DAY 3: FROM CUSCO TO MAUKALLACTA AND CEDROCHAYOQ The guide will meet you at the hotel to leave Cusco (7:00 am) in our private vehicle, we will drive for 2½ hours towards Maukallacta Inca site. We will hike for about one hour and half to the mythical Inca site called Maukallacta (2,900 meters) where we will enjoy our snack and hear stories about the Ayar brothers and wives, founders of the Inca civilization. After a hike and visit this amazing and sacred Inca site, we will enjoy lunch. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

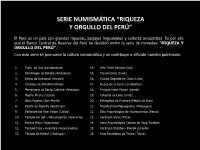

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

Moche Route – the Lost Kingdoms

MOCHE ROUTE – THE LOST KINGDOMS MAY 2019 MON 20 CIVILIZATIONS AT NORTHERN PERU: MOCHE AND CHIMU (L,D) 10:40 Airport pick up. 11:15 Visit to Site Museum at Huaca de la Luna, where you can admire a great collection of beatiful pottery and its iconography, created by Moche people. The tour continues to the archaeologycal area, a huge monument that exhibits colorful mural on decorated wall. This construction represents one of the most important and magnificient edifications of ancient Perú. 13:30 Seafood buffet at Huanchaco beach. 14:15 Vivential experience admiring typical fishing boats called “caballitos de totora”. Made of totora fiber, these ancient boats are still used every day by local fishermen. You can also experience a ride in one of these boats. 15:15 Visit to Chan Chan – Biggest mud city in the world, Cultural heritage of humanity. Built by Chimu inhabitants (700 dC – 1500 dC) is an impressive edification with very high walls, friezes and designs of great urban planification. 17:00 Hotel check in 20:00 Dinner TUE 21 THE AMAZING TREASURES OF THE LORD OF SIPAN (B, L) 06:15 Buffet breakfast 06:45 We´ll head to Magadalena de Cao, 70 kms. north of Trujillo, a few minutes from the shore, first stop to visit El Brujo complex. We´ll visit first the archaeolgycal zone, similar style to Huaca de la Luna, but different murals. We´ll continue to visit Cao Museum that shows the incredible and excellent preserved mummy of one of female governors of Moche culture, called Lady of Cao. -

Course Description Famous for the Inka Site of Machu Picchu, Peru

University of South Dakota Faculty Led Program- Summer 2017 Peruvian Archaeology: The Inkas and their Ancestors (ANTH 490) Course Description Famous for the Inka site of Machu Picchu, Peru has a fascinating prehistory that goes deeper in time from the origins of animal and plant domestication to the development of early states like the Moche and the Wari. This course is a survey of the ancient cultures and main archaeological sites of the central Andes including Chavín de Huántar and its religious center, Nazca and its famous lines, Huacas de Moche and its hyper- realistic ceramics, Huari and Pikillaqta and their high walled compounds, Chan Chan and its adobe citadel, and Macchu Picchu and Sacsayhuaman and their fine stone architecture. Topics will include the origins of plant and animal domestication, ceremonial and domestic architecture, ritual and religion, and the formation of state and empires. While we will mainly discuss the material culture (architecture, ceramics, human and animal bones, stone tools) excavated from archaeological sites ethnohistoric and ethnographic sources (maps, manuscripts, drawings, folklore, oral traditions) will also be incorporated when appropriate. The course will also include guided visits to museums and archaeological sites in and nearby Lima. Learning outcomes After taking this course students should be familiar with the sites, chronology, and major debates of Peruvian archaeology and more specifically, they should be able to: Describe the ecological diversity and the adaptation of the diverse prehispanic cultures of Peru Explain the origins of agriculture, animal domestication, and social complexity- including states and empires that took place in Prehispanic Peru. Identify some of the material culture of the most recognizable prehispanic groups of Peru Demonstrate spatial and chronological knowledge of the Prehispanic cultures of Peru. -

Languages of the Middle Andes in Areal-Typological Perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran

Languages of the Middle Andes in areal-typological perspective: Emphasis on Quechuan and Aymaran Willem F.H. Adelaar 1. Introduction1 Among the indigenous languages of the Andean region of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile and northern Argentina, Quechuan and Aymaran have traditionally occupied a dominant position. Both Quechuan and Aymaran are language families of several million speakers each. Quechuan consists of a conglomerate of geo- graphically defined varieties, traditionally referred to as Quechua “dialects”, not- withstanding the fact that mutual intelligibility is often lacking. Present-day Ayma- ran consists of two distinct languages that are not normally referred to as “dialects”. The absence of a demonstrable genetic relationship between the Quechuan and Aymaran language families, accompanied by a lack of recognizable external gen- etic connections, suggests a long period of independent development, which may hark back to a period of incipient subsistence agriculture roughly dated between 8000 and 5000 BP (Torero 2002: 123–124), long before the Andean civilization at- tained its highest stages of complexity. Quechuan and Aymaran feature a great amount of detailed structural, phono- logical and lexical similarities and thus exemplify one of the most intriguing and intense cases of language contact to be found in the entire world. Often treated as a product of long-term convergence, the similarities between the Quechuan and Ay- maran families can best be understood as the result of an intense period of social and cultural intertwinement, which must have pre-dated the stage of the proto-lan- guages and was in turn followed by a protracted process of incidental and locally confined diffusion.