Tensions in the Greek Symposium Julia Burns Submitted in Fulfillment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Common Wine Cult of Christ and the Orphic Dionysos: the Wine and Vegetation Saviour Deity Dionysos As Model for the Dying and Rising Christ

REL 4990, MA thesis. Culture and Ideas, History of Religion. Autumn 2010. Maritha E. Gebhardt. Page: 1 The common wine cult of Christ and the Orphic Dionysos: the wine and vegetation saviour deity Dionysos as model for the dying and rising Christ. MA Thesis, Master's Programme in Culture and Ideas, History of Religion, Department of Culture and Oriental Languages, Autumn 2010, by Maritha Elin Gebhardt. Synopsis: In 2005 the Hebrew University Excavation Project unearthed a small incense burner from the fourth century C.E. in the Jewish capital of the Galilee, Sepphoris, depicting a crucified figure, Bacchic satyrs and maenads, and the Christian representation of the sacrifice of Isaac in symbolic form as a ram caught in the thicket of a bush. Five years later the book Orphism and Christianity in Late Antiquity, by Herrero de Jáuregui, refers to two large funerary cloths, one depicts a Dionysiac scene similar to the murals from the Villa dei Misteri and the other one show scenes from the life of Jesus and Mary, both found in the same tomb in Egypt. Both of these depictions testify to the continued syncretism of the Orphic and the Christian symbols and that people in the Hellenistic era found the figure of Christ similar to the Bacchic Orpheus. In my thesis I claim that the dying and rising saviour deity of Dionysos is the forerunner to the dying and rising saviour deity of Christ. I claim that I will prove this by showing that the cult of Christ is a wine cult. The epiphany of Jesus was as a human guest at a party, turning water into wine at the wedding-feast at Cana in John 2:1-11, likewise the epiphany of the wine-god Dionysos is in a similar scene as the Cana-miracle, where he turns water into wine (Achilleus Tatius' De Leucippes et Clitophontis amoribus 2.2:1-2.3:1). -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

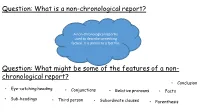

What Is a Non-Chronological Report?

Question: What is a non-chronological report? A non-chronological report is used to describe something factual. It is similar to a fact file. Question: What might be some of the features of a non- chronological report? • Conclusion • Eye-catching heading • Conjunctions • Relative pronouns • Facts • Sub-headings • Third person • Subordinate clauses • Parenthesis Non-chronological report planner- Introduction: • What is the report about? • A brief overview of the Greek gods- • What did the Greeks believe? • Who are they? • Where did they live? Paragraph 1: Paragraph 2: • Create a headline for this section. Something that relates to the This should be a God that contrasts one of your 12 Olympians in gods of Mount Olympus. paragraph 1. • Choose one of the first 3 gods from the ‘Greek gods fact sheet’ to • Create a headline for this section. humans. write about. • Choose one of the second 3 gods from the ‘Greek gods fact sheet’ to • What they were the god or goddess of and their power or skill. write about. • Describe what they look like (you might want to use the pictures • What they were the god or goddess of and their power or skill. on the information cards to you with this) and something they • Describe what they look like (you might want to use the pictures on might carry or have (this might be a weapon, tool or pet). the information cards to you with this) and something they might • Who are they related to? Who are their children? carry or have (this might be a weapon, tool or pet). • Any similarities to one of the Viking gods? How/why are they • Who are they related to? Who are their children? similar? • Any similarities to one of the Viking gods? How/why are they • Any other interesting facts. -

A God Why Is Hermes Hungry?1

CHAPTER FOUR A GOD WHY IS HERMES HUNGRY?1 Ἀλλὰ ξύνοικον, πρὸς θεῶν, δέξασθέ με. (But by the gods, accept me as house-mate) Ar. Plut 1147 1. Hungry Hermes and Greedy Interpreters In the evening of the first day of his life baby Hermes felt hungry, or, more precisely, as the Homeric Hymn to Hermes in which the god’s earliest exploits are recorded, says, “he was hankering after flesh” (κρειῶν ἐρατίζων, 64). This expression reveals only the first of a long series of riddles that will haunt the interpreter on his slippery journey through the hymn. After all, craving for flesh carries overtly negative connotations.2 In the Homeric idiom, for instance, the expression is exclusively used as a predicate of unpleasant lions.3 Nor does it 1 This chapter had been completed and was in the course of preparation for the press when I first set eyes on the important and innovative study of theHymn to Hermes by D. Jaillard, Configurations d’Hermès. Une “théogonie hermaïque”(Kernos Suppl. 17, Liège 2007). Despite many points of agreement, both the objectives and the results of my study widely diverge from those of Jaillard. The basic difference between our views on the sacrificial scene in the Hymn (which regards only a section of my present chapter on Hermes) is that in the view of Jaillard Hermes is a god “who sac- rifices as a god” (“un dieu qui sacrifie en tant que dieu,” p. 161; “Le dieu n’est donc, à aucun moment de l’Hymne, réellement assimilable à un sacrificateur humain,” p. -

Performance and Visual Culture in Etruria: 7Th � 2Nd Century BC

Performance and Visual Culture in Etruria: 7th - 2nd Century BC Stephanie Anne Layton Marietta, Georgia Bachelor of Arts, The George Washington University, 2003 Master of Arts, Florida State University, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McIntire Department of Art University of Virginia December 2013 © Copyright by Stephanie Anne Layton All rights Reserved December 2013 Abstract The Etruscan iconographic record is the primary source of information regarding performance activities, which include dance, music, gaming, ritual, spectacle, and athletics. In this study, performance theory is used as a framework for analyzing Etruscan material culture related to emically constructed and provisionally identified performance activities and ascertaining their meaning. Although evidence for Etruscan cultural activity, beliefs, and social interaction is limited, especially given the paucity of textual information, the application of performance theory to the archaeological record provides a means to analyze public and private transmission of messages, relationships, experiences, and cultural behaviors primarily in funerary and civic contexts. Although numerous Etruscan performances have been investigated individually by prior scholarship, performance theory has not been previously applied to Etruscan art and architecture and, therefore, this work takes a new approach towards the analysis of the archaeological record. Evidence included in this study dates between the 8th -2nd centuries BC and consists of wall painting, painted and relief vase decoration, stone and terracotta relief sculpture, engraved gems, and bronze mirrors, decorative attachments, figurines, and vessels. It is only through the study of such varied materials from a wide chronological range that a more complete understanding of Etruscan performance emerges. -

This Book — the Only History of Friendship in Classical Antiquity That Exists in English

This book — the only history of friendship in classical antiquity that exists in English - examines the nature of friendship in ancient Greece and Rome from Homer (eighth century BC) to the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century AD. Although friendship is throughout this period conceived of as a voluntary and loving relationship (contrary to the prevailing view among scholars), there are major shifts in emphasis from the bonding among warriors in epic poetry, to the egalitarian ties characteristic of the Athenian democracy, the status-con- scious connections in Rome and the Hellenistic kingdoms, and the commitment to a universal love among Christian writers. Friendship is also examined in relation to erotic love and comradeship, as well as for its role in politics and economic life, in philosophical and religious communities, in connection with patronage and the private counsellors of kings, and in respect to women; its relation to modern friendship is fully discussed. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEYTHEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY Friendship in the classical world Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 147.231.79.110 on Thu May 20 13:43:40 BST 2010. Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010 KEY THEMES IN ANCIENT HISTORY EDITORS Dr P. -

Classical Greek Comedy

Chapter 8: Early Greek Comedy and Satyr Plays Mark Damen (2012) !I. Introduction: An Overview of Classical and Post- Classical Greek Comedy Though comedy in the broadest sense of the term—any kind of humorous material—is at least as old as Greek civilization, historical evidence suggests dramatic comedy first arose in or just before the Classical Age. Like tragedy, ancient Greek komoidia, the word from which we get "comedy," eventually found a home at the Dionysia, though it achieved official status only significantly later than its close theatrical kin. The data further suggest this so-called Old Comedy was probably not the first form of comic drama performed at the Dionysia. Instead, pre-classical playwrights were composing short humorous "satyr plays" featuring boisterous bands of lusty, mischievous woodland spirits called satyrs. During the Classical Age, satyr plays followed the presentation of tragic trilogies, making them the oldest form of comic drama extant. If slower to rise than the satyr play, Old Comedy eventually gained attention and acclaim—and finally pre-eminence—by the end of the fifth century. Indeed, the first writer of this genre whose works are preserved entire is Aristophanes, a late classical comic poet whose plays, like Old Comedy in general, are raucous and political, closely tied to current affairs. He often satirizes Athenian politicians and public figures with ribald wit, usually proposing wild and extravagant solutions, both serious and satirical, to a wide range of problems confronting society in his day: everything from tactics for ending the Peloponnesian War to tips on keeping the devilish Euripides Source URL: http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/ClasDram/chapters/081earlygkcom.htm Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/ENGL401#2.1.1 Attributed to: Mark Damen www.saylor.org Page 1 of 23 in line. -

Observing Genre in Archaic Greek Skolia and Vase-Painting*

chapter 6 Observing Genre in Archaic Greek Skolia and Vase-Painting* Gregory S. Jones Skolion. A rather general term covering any after-dinner song; indeed, poems originally written for entirely different purposes (for example poems by Stesichorus) could be performed by a guest as a contribution to the entertainment, and called a skolion. The name comes from the irregular or ‘crooked’ order in which such pieces were offered during the evening, as opposed to the regular order ἐπὶ δεξιά in which everyone gave their compulsory piece after dinner.1 ∵ Introduction Fowler’s definition reflects a longstanding view held by a majority of scholars who have studied songs called skolia but generally assume that the term σκό- λιον lacked any real generic significance in antiquity.2 Perhaps because of their well-known depictions in comedy (where their popularity among the masses appears to have been exploited for laughs), the Attic skolia are regularly trivial- ized as ‘light’ and ‘informal’ compared to other types of melic poetry, giving rise to a sweeping and often negative generalization of the term skolion that even * I would like to thank the organizers, hosts, and participants of the conference at Delphi for facilitating such an enjoyable and stimulating event. I am especially grateful to Richard Martin, Alan Shapiro, and Vanessa Cazzato for helpful suggestions and conversations on many aspects of this paper. The present study incorporates several arguments first presented in my dissertation ‘Singing the Skolion: a Study of Poetics and Politics in Ancient Greece’ (2008 PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University). All translations are my own. -

Homeric Constructions: the Reception of Homeric Authority

Homeric Constructions: The Reception of Homeric Authority _______________________________________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by Andrew M Smith Professor David Schenker, Dissertation Advisor December 2014 © Copyright by Andrew M Smith 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled Homeric Constructions: The Reception of Homeric Authority Presented by Andrew Smith, A candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor David Schenker Professor Raymond Marks Professor Daniel Hooley Professor Susan Langdon Acknowledgments I would like to thank those faculty members who have assisted me in this project. Without the inspiration of Professor John Miles Foley, I would not have been pressed to imagine the parameters of this project, nor have the apparatus with which to begin it. I sincerely appreciate the organizational assistance of Professor Raymond Marks, whose guidance in the academic craft provided me with the order and schema of this project. I also would like to acknowledge Professor Daniel Hooley, who introduced me to reception theory, and Professor Susan Langdon, who gave me a non-literary perspective on Greek culture which -

The Iconography of the Athenian Hero in Late Archaic Greek Vase-Painting

The Iconography of the Athenian Hero in Late Archaic Greek Vase-Painting Elizabeth Anne Bartlett Tucson, Arizona Bachelor of Art, Scripps College, 2006 Master of Art, University of Arizona, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy McIntire Department of Art University of Virginia May 2015 ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ ______________________________ –ABSTRACT– This study questions how Athenian vase-painters represented heroic figures during the late sixth and early fifth centuries B.C. – specifically from the death of Peisistratos in 528 B.C. to the return of Theseus' bones to Athens in 475/4 B.C. The study focuses on three specific Attic cult heroes with a strong presence both in the Greek world and on Athenian vases: Herakles, Theseus, and Ajax. Although individual studies have been published regarding various aspects of these three heroes, such as subject matter, cult worship, literary presence, and social history, the current one departs from them by categorizing, comparing, and contrasting the different portrayals of the three chosen heroes. Using Athenian vases as the primary form of evidence, the current study endeavors to uncover how individual iconography can – or cannot – identify the heroic figure. By using an iconographic approach of looking at attributes, dress, gestures, poses, and composition, a more complete picture of the image of the hero may be understood. Evidence of both the cult of, and importance of, the Athenian hero is stressed both in ancient texts and through archaeological evidence, thus supplemental material is taken into consideration. Illustrations of Greek heroes can be found on a variety of vase shapes of various techniques, and the accompanying catalogue includes almost 300 examples.