Jamaica for Germany?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

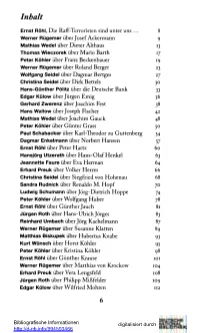

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen Sind Unter Uns

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen sind unter uns ... 8 Werner Rügemer über Josef Ackermann 9 Mathias Wedel über Dieter Althaus 13 Thomas Wieczorek über Mario Barth 17 Peter Köhler über Franz Beckenbauer 19 Werner Rügemer über Roland Berger 23 Wolfgang Seidel über Dagmar Bertges 27 Christina Seidel über Dirk Bettels 30 Hans-Günther Pölitz über die Deutsche Bank 33 Edgar Külow über Jürgen Emig 36 Gerhard Zwerenz über Joachim Fest 38 Hans Wallow über Joseph Fischer 42 Mathias Wedel über Joachim Gauck 48 Peter Köhler über Günter Grass 50 Paul Schabacker über Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg 54 Dagmar Enkelmann über Norbert Hansen 57 Ernst Röhl über Peter Hartz 60 Hansjörg Utzerath über Hans-Olaf Henkel 63 Jeannette Faure über Eva Herman 64 Erhard Preuk über Volker Herres 66 Christina Seidel über Siegfried von Hohenau 68 Sandra Rudnick über Renaldo M. Hopf 70 Ludwig Schumann über Jörg-Dietrich Hoppe 74 Peter Köhler über Wolfgang Huber 78 Ernst Röhl über Günther Jauch 81 Jürgen Roth über Hans-Ulrich Jorges 83 Reinhard Limbach über Jörg Kachelmann 87 Werner Rügemer über Susanne Klatten 89 Matthias Biskupek über Hubertus Knabe 93 Kurt Wünsch über Horst Köhler 95 Peter Köhler über Kristina Köhler 98 Ernst Röhl über Günther Krause 101 Werner Rügemer über Matthias von Krockow 104 Erhard Preuk über Vera Lengsfeld 108 Jürgen Roth über Philipp Mißfelder 109 Edgar Külow über Wilfried Mohren 112 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994503466 Paul Schabacker über Franz Müntefering 115 Christoph Hofrichter über Günther Oettinger 120 Reinhard Limbach über Hubertus Pellengahr 122 Stephan Krull über Ferdinand Piëch 123 Ernst Röhl über Heinrich von Pierer 127 Paul Schabacker über Papst Benedikt XVI. -

Beyond Social Democracy in West Germany?

BEYOND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN WEST GERMANY? William Graf I The theme of transcending, bypassing, revising, reinvigorating or otherwise raising German Social Democracy to a higher level recurs throughout the party's century-and-a-quarter history. Figures such as Luxemburg, Hilferding, Liebknecht-as well as Lassalle, Kautsky and Bernstein-recall prolonged, intensive intra-party debates about the desirable relationship between the party and the capitalist state, the sources of its mass support, and the strategy and tactics best suited to accomplishing socialism. Although the post-1945 SPD has in many ways replicated these controversies surrounding the limits and prospects of Social Democracy, it has not reproduced the Left-Right dimension, the fundamental lines of political discourse that characterised the party before 1933 and indeed, in exile or underground during the Third Reich. The crucial difference between then and now is that during the Second Reich and Weimar Republic, any significant shift to the right on the part of the SPD leader- ship,' such as the parliamentary party's approval of war credits in 1914, its truck under Ebert with the reactionary forces, its periodic lapses into 'parliamentary opportunism' or the right rump's acceptance of Hitler's Enabling Law in 1933, would be countered and challenged at every step by the Left. The success of the USPD, the rise of the Spartacus move- ment, and the consistent increase in the KPD's mass following throughout the Weimar era were all concrete and determined reactions to deficiences or revisions in Social Democratic praxis. Since 1945, however, the dynamics of Social Democracy have changed considerably. -

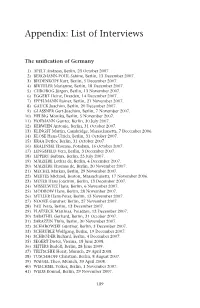

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Plenarprotokoll 16/189

Plenarprotokoll 16/189 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 189. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 26. November 2008 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt II (Fortsetzung): Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) (CDU/CSU) . 20371 A a) Zweite Beratung des von der Bundesregie- rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Geset- Katrin Göring-Eckardt (BÜNDNIS 90/ zes über die Feststellung des Bundes- DIE GRÜNEN) . 20372 B haushaltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr 2009 (Haushaltsgesetz 2009) Monika Griefahn (SPD) . 20373 C (Drucksachen 16/9900, 16/9902) . 20333 A Jörg Tauss (SPD) . 20374 B b) Beschlussempfehlung des Haushaltsaus- schusses zu der Unterrichtung durch die Namentliche Abstimmung . 20375 C Bundesregierung: Finanzplan des Bun- des 2008 bis 2012 (Drucksachen 16/9901, 16/9902, 16/10426) 20333 B Ergebnis . 20378 C 8 Einzelplan 04 Tagesordnungspunkt III: Bundeskanzlerin und Bundeskanzler- Wahl des Bundesbeauftragten für den amt Datenschutz und die Informationsfreiheit (Drucksachen 16/10404, 16/10423) . 20333 B Rainer Brüderle (FDP) . 20333 D Wahl . 20375 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin . 20335 A Oskar Lafontaine (DIE LINKE) . 20341 C Ergebnis . 20380 B Dr. Peter Struck (SPD) . 20346 D 9 Einzelplan 05 Renate Künast (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 20350 C Auswärtiges Amt (Drucksachen 16/10405, 16/10423) . 20376 A Volker Kauder (CDU/CSU) . 20354 D Dr. Werner Hoyer (FDP) . 20376 B Dr. Guido Westerwelle (FDP) . 20357 C Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Bundes- Ludwig Stiegler (SPD) . 20362 A minister AA . 20380 D Dr. Peter Ramsauer (CDU/CSU) . 20365 A Michael Leutert (DIE LINKE) . 20383 C Dr. Guido Westerwelle (FDP) . 20367 A Herbert Frankenhauser (CDU/CSU) . 20384 C Klaus Ernst (DIE LINKE) . 20367 B Jürgen Trittin (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dr. Peter Ramsauer (CDU/CSU) . 20367 C DIE GRÜNEN) . -

Plenarprotokoll 15/56

Plenarprotokoll 15/56 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 56. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 3. Juli 2003 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Marschall des Sejm der Repu- rung als Brücke in die Steuerehr- blik Polen, Herrn Marek Borowski . 4621 C lichkeit (Drucksache 15/470) . 4583 A Begrüßung des Mitgliedes der Europäischen Kommission, Herrn Günter Verheugen . 4621 D in Verbindung mit Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Michael Kauch . 4581 A Benennung des Abgeordneten Rainder Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Steenblock als stellvertretendes Mitglied im a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Michael Programmbeirat für die Sonderpostwert- Meister, Friedrich Merz, weiterer Ab- zeichen . 4581 B geordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 4582 D CSU: Steuern: Niedriger – Einfa- cher – Gerechter Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 4581 B (Drucksache 15/1231) . 4583 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Hermann Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: Otto Solms, Dr. Andreas Pinkwart, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Abgabe einer Erklärung durch den Bun- der FDP: Steuersenkung vorziehen deskanzler: Deutschland bewegt sich – (Drucksache 15/1221) . 4583 B mehr Dynamik für Wachstum und Be- schäftigung 4583 A Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . 4583 C Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 4587 D in Verbindung mit Franz Müntefering SPD . 4592 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4596 D Tagesordnungspunkt 7: Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen DIE GRÜNEN . 4600 A der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4603 B wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Förderung Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ der Steuerehrlichkeit DIE GRÜNEN . 4603 C (Drucksache 15/1309) . 4583 A Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 4603 D b) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- neten Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, Hubertus Heil SPD . -

Of Germany and EMU

Comment [COMMENT1]: NOAM Task Force on Economic and Monetary Union Briefing 3 Second Revision The Federal Republic of Germany and EMU Directorate-General for Research Division for Economic Affairs The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the European Parliament's position. The Commission's recommendation to the Council is that Germany satisfies the criteria for the introduction of a single currency. The EMI notes in its report that, in order to bring the debt ratio back to 60%, considerable further progress towards consolidation is necessary. Luxembourg, 20 April 1998 Contents PE 166.061/rev.2 EMU and Germany Introduction 3 I. Economic convergence 3 (a) Price stability 4 (b) Budget deficits 5 (c) Government debt 8 (d) Participation in the exchange rate mechanism 10 (e) Long-term interest rates 11 (f) Economic growth, unemployment and the current account balance 12 II. Legislative convergence 13 (a) Scope of necessary adaptation of national legislation 13 (b) Overview and legislative action taken since 1994 14 (c) Assessment of compatibility 15 III. The political background 15 (a) The "Euro petition" 15 (b)The Federal Government 16 (c) The Bundesbank 17 (d) The Christian-Democratic Union (CDU) 18 (e) The Christian-Social Union (CSU) 20 (f) The Free Democratic Party (FDP) 20 (g) The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) 21 (h) Bündnis 90/Die Grünen 23 (i) The Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) 23 (j) The debate in the universities 23 (k) Trade and industry 25 (l) The trade unions 26 (m) The German banks 26 Tables and figures Table 1: Germany and the Maastricht criteria 3 Table 2: Inflation 4 Table 3: Government debt dynamics 8 Table 4: Sustainability of debt trends 9 Table 5: Spread of the DEM against median currency 10 Table 6: Long-term interest rates 11 Figure 1: National consumer price index 5 Figure 2: Government deficits 6 Figure 3: State of government debt 8 Figure 4: Development of long-term interest rates 12 Figure 5: Real economic growth and unemployment rates 13 Authors: C. -

Plenarprotokoll 16/220

Plenarprotokoll 16/220 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 220. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 7. Mai 2009 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abgeord- ter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: neten Walter Kolbow, Dr. Hermann Scheer, Bundesverantwortung für den Steu- Dr. h. c. Gernot Erler, Dr. h. c. Hans ervollzug wahrnehmen Michelbach und Rüdiger Veit . 23969 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Barbara Höll, Dr. Axel Troost, nung . 23969 B Dr. Gregor Gysi, Oskar Lafontaine und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuermiss- Absetzung des Tagesordnungspunktes 38 f . 23971 A brauch wirksam bekämpfen – Vor- handene Steuerquellen erschließen Tagesordnungspunkt 15: – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der Barbara Höll, Wolfgang Nešković, CDU/CSU und der SPD eingebrachten Ulla Lötzer, weiterer Abgeordneter Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Bekämp- und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuer- fung der Steuerhinterziehung (Steuer- hinterziehung bekämpfen – Steuer- hinterziehungsbekämpfungsgesetz) oasen austrocknen (Drucksache 16/12852) . 23971 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Fi- Christine Scheel, Kerstin Andreae, nanzausschusses Birgitt Bender, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE – zu dem Antrag der Fraktionen der GRÜNEN: Keine Hintertür für Steu- CDU/CSU und der SPD: Steuerhin- erhinterzieher terziehung bekämpfen (Drucksachen 16/11389, 16/11734, 16/9836, – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. 16/9479, 16/9166, 16/9168, 16/9421, Volker Wissing, Dr. Hermann Otto 16/12826) . 23971 B Solms, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der Lothar Binding (Heidelberg) (SPD) . 23971 D FDP: Steuervollzug effektiver ma- Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 23973 A chen Eduard Oswald (CDU/CSU) . -

German Post-Socialist Memory Culture

8 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Bouma German Post-Socialist MemoryGerman Culture Post-Socialist Amieke Bouma German Post-Socialist Memory Culture Epistemic Nostalgia FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS German Post-Socialist Memory Culture FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. Monographs or edited volumes critically interrogate the politics of heritage and dynamics of memory, as well as the theoretical implications of landscapes and mass violence, nationalism and ethnicity, heritage preservation and conservation, archaeology and (dark) tourism, diaspora and postcolonial memory, the power of aesthetics and the art of absence and forgetting, mourning and performative re-enactments in the present. Series Editors Ihab Saloul and Rob van der Laarse, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Editorial Board Patrizia Violi, University of Bologna, Italy Britt Baillie, Cambridge University, UK Michael Rothberg, University of Illinois, USA Marianne Hirsch, Columbia University, USA Frank van Vree, NIOD and University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS German Post-Socialist Memory Culture Epistemic Nostalgia Amieke Bouma Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Kalter Abbruch Source: Bernd Kröger, Adobe Stock Cover -

Panorama V. 26.11.2020 DDR-Bürgerrechtler

Panorama v. 26.11.2020 DDR-Bürgerrechtler: Vom SED-Gegner zum Corona-Leugner Anmoderation Anja Reschke: „Das Robert Koch Institut hat auf der Corona Deutschlandkarte eine neue Farbe eingeführt. Pink. Pink steht für 500 bis 1000 Neuinfektionen pro 100.000 Einwohner innerhalb von 7 Tagen. Alarm- farbe sozusagen. Während also ganz Deutschland eher gelb orange rot ist, sticht tatsächlich ein pinker Punkt heraus. Im Kreis Hildburghausen, südliches Thüringen an der Grenze zu Bayern. Seit gestern gilt dort strenger Lockdown. Aber schauen Sie mal, wie die Stimmung gestern Abend in der Fußgängerzone war:“ Einspielfilm: „Oh wie ist das schön. Gut 400 Menschen in der Fußgängerzone. Was ist denn schön? Dass so viele krank sind? Dass Kitas, Schulen, Feuerwachen in Quarantäne sind? und Menschen sterben? Oh, wie ist das schön? Was überhaupt? Ohne Maske unterwegs zu sein? Diese schlimme Einschränkung, dieses Symbol von Unterdrückung?“ „Von was sprechen diese Menschen? Welche Diktatur? In diesem Land kann sich jeder in den Vor- dergrund spielen, wie er lustig ist, er kann demonstrieren, auch das macht der Staat möglich mit Einsatz von Polizeischutz, sogar in Corona-Zeiten, er kann breitbeinig seine Meinung herausplärren, überall und jedem gegenüber. Und es passiert ihm gar nichts. Das Diktatur zu nennen, ist arrogant und hochmütig. Aber was man wirklich überhaupt nicht mehr versteht, ist, wenn es von Menschen kommt, die eine Diktatur miterlebt haben. Die es besser wissen müssten, weil sie vor 30 Jahren eine Revolution gegen die Diktatur angeführt haben. Helden waren. Sie müssten wissen, was es bedeutet, wenn man seine Meinung nicht sagen kann, weil man dann in Bautzen, im Zuchthaus landet, sie haben es persönlich erlitten. -

Political Scandals, Newspapers, and the Election Cycle

Political Scandals, Newspapers, and the Election Cycle Marcel Garz Jil Sörensen Jönköping University Hamburg Media School April 2019 We thank participants at the 2015 Economics of Media Bias Workshop, members of the eponymous research network, and seminar participants at the University of Hamburg for helpful comments and suggestions. We are grateful to Spiegel Publishing for access to its news archive. Daniel Czwalinna, Jana Kitzinger, Henning Meyfahrt, Fabian Mrongowius, Ulrike Otto, and Nadine Weiss provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Hamburg Media School. Corresponding author: Jil Sörensen, Hamburg Media School, Finkenau 35, 22081 Hamburg, Germany. Phone: + 49 40 413468 72, fax: +49 40 413468 10, email: [email protected] Abstract Election outcomes are often influenced by political scandal. While a scandal usually has negative consequences for the ones being accused of a transgression, political opponents and even media outlets may benefit. Anecdotal evidence suggests that certain scandals could be orchestrated, especially if they are reported right before an election. This study examines the timing of news coverage of political scandals relative to the national election cycle in Germany. Using data from electronic newspaper archives, we document a positive and highly significant relationship between coverage of government scandals and the election cycle. On average, one additional month closer to an election increases the amount of scandal coverage by 1.3%, which is equivalent to an 62% difference in coverage between the first and the last month of a four- year cycle. We provide suggestive evidence that this pattern can be explained by political motives of the actors involved in the production of scandal, rather than business motives by the newspapers. -

Drucksache 14/515 14. Wahlperiode 16

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/515 14. Wahlperiode 16. 03. 99 Beschlußempfehlung und Bericht des Innenausschusses (4. Ausschuß) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Vera Lengsfeld, Norbert Otto (Erfurt), Hartmut Büttner (Schönebeck) und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU – Drucksache 14/89 – Überlassung der Akten der Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit der ehemaligen DDR durch die Regierung der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika A. Problem Die amerikanische Regierung hat im Jahr 1989/90 durch die CIA Dossiers und Materialien sowie mikroverfilmte Akten der HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung) des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit der DDR sichergestellt. Ziel des Antrages ist, daß diese Unterlagen der Gauck-Behörde zur Verfügung gestellt werden sollen und die Bundesregierung bei ihren Bemühungen um die Rückführung dieses Materials nach Deutschland nachdrücklich unterstützt wird. B. Lösung Annahme des Antrages. Einstimmigkeit im Ausschuß C. Alternativen Keine D. Kosten Keine Drucksache 14/515 – 2 – Deutscher Bundestag – 14. Wahlperiode Beschlußempfehlung Der Bundestag wolle beschließen, den Antrag in der nachfolgenden Fassung anzunehmen: Der Deutsche Bundestag bittet die amerikanische Regierung, die im Jahr 1989/90 von der CIA sichergestellten Dossiers und Materialien sowie mikroverfilmten Akten der HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklä- rung) des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit der DDR der Gauck- Behörde zur Verfügung zu stellen. Er unterstützt die Bundesregie- rung nachdrücklich in ihren Bemühungen um die Rückführung die- ses Materials nach Deutschland. Bonn, den 8. März 1999 Der Innenausschuß Dr. Willfried Penner Gisela Schröter Hartmut Büttner (Schönebeck) Vorsitzender Berichterstatterin Berichterstatter Hans-Christian Ströbele Dr. Edzard Schmidt-Jortzig Berichterstatter Berichterstatter Ulla Jelpke Berichterstatterin Deutscher Bundestag – 14. Wahlperiode – 3 – Drucksache 14/515 Bericht der Abgeordneten Gisela Schröter, Hartmut Büttner (Schönebeck), Hans-Christian Ströbele, Dr. -

The SPD's Electoral Dilemmas

AICGS Transatlantic Perspectives September 2009 The SPD’s Electoral Dilemmas By Dieter Dettke Can the SPD form a Introduction: After the State Elections in Saxony, Thuringia, and Saarland coalition that could effec - August 30, 2009 was a pivotal moment in German domestic politics. Lacking a central tively govern on the na - theme in a campaign that never got quite off the ground, the September 27 national elec - tional level, aside from tions now have their focal point: integrate or marginalize Die Linke (the Left Party). This another Grand Coali - puts the SPD in a difficult position. Now that there are red-red-green majorities in Saarland tion? and Thuringia (Saarland is the first state in the western part of Germany with such a major - How has the SPD gone ity), efforts to form coalitions with Die Linke might well lose their opprobrium gradually. From from being a leading now on, coalition-building in Germany will be more uncertain than ever in the history of the party to trailing in the Federal Republic of Germany. On the one hand, pressure will mount within the SPD to pave polls? the way for a new left majority that includes Die Linke on the federal level. On the other hand, Chancellor Angela Merkel and the CDU/CSU, as well as the FDP, will do everything to make the prevention of such a development the central theme for the remainder of the electoral campaign. The specter of a red-red-green coalition in Berlin will now dominate the political discourse until Election Day. Whether this strategy will work is an open question.