A Rebellion in Burma: the Sagaing Uprising of 1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

A Comparative Study of Amitav Ghosh's the Glass Palace

An Open Access Journal from The Law Brigade Publishers 127 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF AMITAV GHOSH’S THE GLASS PALACE AND SUDHA SHAH’S THE KING IN EXILE Written by Akarshak Bose* & Dr. V Rema** * 4th Year B Tech CSE Student, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram, Chennai, India ** Professor and HoD Department of English and Other foreign languages SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Ramapuram ABSTRACT The present study is a comparison between The Glass Palace by Amitav Ghosh and The king in exile by Sudha Shah. Both of them deals with the similar historical plot and shares common places. The Royal Family of Burma King Thibaw , who used to have the unchallenged power of life and death over the Burmese people are now living exile. They have to get approval from the British on every personal matter of their lives. The life in exile was extremely strange and frustrating for the once most powerful family of Burma. The present study also deals with how situation changes and people’s responses or readiness to accept the changes. The Central Character of The Glass Palace Rajkumar when came to Mandalay he had nothing , created an empire of timber and later on he left as a refugee when Japanese invaded their Country, whereas being the king of Burma, when he lost his kingdom to British and deported to India , he was forced to comply with little earning. This comparison in being set up on the grounds of Common places, Common plots and common themes between the two books. Keywords- Amitav Ghosh, Sudha Shah, King Thibaw, Burma, Mandalay, Exile INTRODUCTION The comparative study, between the glass palace by Amitav Ghosh and the king in exile by Sudha Shah shared several things in common. -

Beautiful Myanmar

BEAUTIFUL MYANMAR “Warmest Greetings from HEARTH Travels & Tours Company Limited.” Our Travels & Tours business was founded since 1995 December with the name of “Color Connection Travels & Tours” (REG : NO. 1746 – 1995 / 1996) at Room 43, Bldg 2, Mayangon Housing Complex, 8th mile junction (North) Yangon, Myanmar. We would like to introduce with a new name “HEARTH Travels & Tours” which upgrade our service and business with experienced staffs. Whenever you are thinking to travel around the world just remember that there is a travelling company which is the “Heart of the Earth.” “Welcome to BEAUTIFUL MYANMAR.” No.486, Theinbyu Road, Room (B2), Mingalar Taung Nyunt Township, Yangon, Myanmar. Tel/Fax :+ (951) 200958, Email : [email protected] Our Services :: Package Tours :: F.I.T Tours :: Business Tours :: Special Interest Tours :: Eco-Tours :: Hotel Reservations :: Air Ticketing ( International / Domestic ) :: Train and Express Ticketing Shwe Dagon Pagoda - Yangon :: Visa Support Yangon, is the biggest city of Myanmar. :: Guide Services International standard golf courses, :: Car Rental museums and beautiful parks are popular. The Shwedagon Pagoda, more than 2500 Nay Pyi Taw, the administrative capital of the years old towering almost 100m above sea Republic of the Union of Myanmar. Centrally level, promises a spectacular sight. located, it is 391 km from Yangon and 302 km Environs are Thanlyin, Bago, Kyaikhtiyo from Mandalay, being easily accessible from and Twante. all parts of the country. The environs of Nay Mandalay, the last royal capital of Pyi Taw comprise (8) townships. Myanmar kings, is situated at the foot of Hluttaw (Parliament House) – Nay Pyi Taw the Mandalay Hill on the east bank of the Ayeyarwaddy River. -

Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao

ICS TRAVEL GROUP is one of the first international DMCs to open own offices in our destinations and has since become a market leader throughout the Mekong region, Indonesia and India. As such, we can offer you the following advantages: Global Network. Rapid Response. With a centralised reservations centre/head All quotation and booking requests are answered office in Bangkok and 7 sales offices. promptly and accurately, with no exceptions. Local Knowledge and Network. Innovative Online Booking Engine. We have operations offices on the ground at every Our booking and feedback systems are unrivalled major destination – making us your incountry expert in the industry. for your every need. Creative MICE team. Quality Experience. Our team of experienced travel professionals in Our goal is to provide a seamless travel experience each country is accustomed to handling multi- for your clients. national incentives. Competitive Hotel Rates. International Standards / Financial Stability We have contract rates with over 1000 hotels and All our operational offices are fully licensed pride ourselves on having the most attractive pricing and financially stable. All guides and drivers are strategies in the region. thoroughly trained and licensed. Full Range of Services and Products. Wherever your clients want to go and whatever they want to do, we can do it. Our portfolio includes the complete range of prod- ucts for leisure and niche travellers alike. ICS TRAVEL ICSGROUPTRAVEL GROUP Contents Introduction 3 Tours 4 Cruises 20 Hotels 24 Yangon 24 Mandalay 30 Bagan 34 Mount Popa 37 Inle Lake 38 Nyaung Shwe 41 Ngapali 42 Pyay 45 Mrauk U 45 Ngwe Saung 46 Excursions 48 Hotel Symbol: ICS Preferred Hotel Style Hotel Boutique Hotel Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao Lahe INDIA INDIA Myitkyina CHINA CHINA Bhamo Muse MYANMAR Mogok Lashio Hsipaw BANGLADESHBANGLADESH Mandalay Monywa ICS TRA VEL GR OUP Meng La Nyaung Oo Kengtung Mt. -

The Glass Palace

HISTORY PROJECT “To use the past to justify the present is bad enough—but it’s just as bad to use the present to justify the past.” — Amitav Ghosh, The Glass Palace Srijon Sinha Class XI-H1 – The Shri Ram School, Moulsari THE GLASS PALACE WRITTEN BY AMITAV GHOSH TABLE OF CONTENTS Research Question .......................................................................... 2 Abstract ....................................................................................... 2 Reason for choosing the topic ......................................................................2 Methods and materials ...............................................................................2 Hypothesis ..............................................................................................2 Main Essay .................................................................................... 2 Background and context .............................................................................2 Explanation of the theme ...........................................................................3 Interpretation and analysis .........................................................................5 Conclusion .................................................................................... 5 Bibliography ................................................................................. 6 1 RESEARCH QUESTION What are the historical, cultural and political forces that shape the progression of the plot, the characters, their actions, and furthermore, how do the -

Thai-Burmese Warfare During the Sixteenth Century and the Growth of the First Toungoo Empire1

Thai-Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century 69 THAI-BURMESE WARFARE DURING THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND THE GROWTH OF THE FIRST TOUNGOO EMPIRE1 Pamaree Surakiat Abstract A new historical interpretation of the pre-modern relations between Thailand and Burma is proposed here by analyzing these relations within the wider historical context of the formation of mainland Southeast Asian states. The focus is on how Thai- Burmese warfare during the sixteenth century was connected to the growth and development of the first Toungoo empire. An attempt is made to answer the questions: how and why sixteenth century Thai-Burmese warfare is distinguished from previous warfare, and which fundamental factors and conditions made possible the invasion of Ayutthaya by the first Toungoo empire. Introduction As neighbouring countries, Thailand and Burma not only share a long border but also have a profoundly interrelated history. During the first Toungoo empire in the mid-sixteenth century and during the early Konbaung empire from the mid-eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries, the two major kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia waged wars against each other numerous times. This warfare was very important to the growth and development of both kingdoms and to other mainland Southeast Asian polities as well. 1 This article is a revision of the presentations in the 18th IAHA Conference, Academia Sinica (December 2004, Taipei) and The Golden Jubilee International Conference (January 2005, Yangon). A great debt of gratitude is owed to Dr. Sunait Chutintaranond, Professor John Okell, Sarah Rooney, Dr. Michael W. Charney, Saya U Myint Thein, Dr. Dhiravat na Pombejra and Professor Michael Smithies. -

The Military Force of Toungoo Dynasty in the 16Th Century During the Burmese-Siamese War

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2021, Vol. 11, No. 7, 527-537 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.07.012 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Military Force of Toungoo Dynasty in the 16th Century During the Burmese-Siamese War XING Cheng Northeastern University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110169, China Toungoo Dynasty was a powerful feudal regime in the history of Burma. Upon the rise of Toungoo Dynasty, it sought to extend territory by arms, starting to have wars with the Empire Ming (China), Ayutthaya Dynasty (Siam/Thailand) and Lan Xang (Laos). The war between Burma and Siam lasted for more than two centuries, from 1548 to 1810. However, from strategy view, the whole Burmese-Siamese War was the game between China (Ming and Qing Dynasties) and Burma (Toungoo and Konbaung Dynasties). In the whole process, most of the fierce battles took place in the 16th century, the inception phase of the war. So, the 16th century was a very important period for us if we want to have a research on the military force of Toungoo Dynasty. Keywords: Burma, Toungoo Dynasty, Tabinshwehti, Bayinnaung, Siam, Ayutthaya Dynasty Ⅰ Introduction Toungoo Dynasty was an important feudal regime in the history of Burma which was built by military means. This system deeply influenced the development of Burma. Until modern times, in Burma, military governments still appear now and then. In the 16th century, Burma had the best military potentials in Southeast Asia because of its special military system, letting it have the ability to mobilize a large army when the wars came. Benefiting from the Empire Ming’s conservative policy and the relatively weak military power of other Southeast Asian countries, Toungoo Dynasty rapidly started its expansion. -

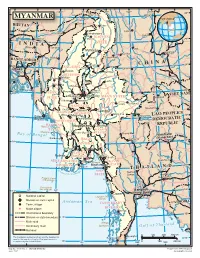

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of an Eighteenth-Century Burmese Monk

Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of an Eighteenth‐Century Burmese Monk (version 1.1) April 02, 2012 Alexey Kirichenko One of the few relatively well-known episodes in the eighteenth-century history of monastic Buddhism in Burma is the debate on how novices should be dressed when going outside of the monastery to collect alms food.1 Sometimes referred to as the ekaṃsika-pārupana or the “one shoulder” vs. the “two shoulder” controversy, the debate revolved around the issue of whether novices should wear their robes in the same fashion as the monks or whether they should be dressed in a specifically distinct manner. According to a number of influential Burmese sources, this issue caused a serious rift in the saṃgha, which lasted for almost a century and was remedied only through resolute actions of King Badon-min (Bodawpaya, 1782–1819). As a subject for debate and a cause for monastic reform, the “one shoulder” vs. the “two shoulder” controversy seems a typical case for Theravādin monasticism. The tendency of Theravāda monks to emphasize seemingly minor issues of discipline or ritual practice over the matters of doctrine is long noted in the literature.2 Such matters as the manner of wearing the robe or carrying the alms bowl, the acceptability of wearing footwear (in general or in specific contexts), the propriety of certain types of monastic fans, the permissibility of smoking after noon, the rules for intoning Pāli ceremonial and ritual formulas, calendrical practices, etc., engaged the best minds in the saṃgha for decades. The debates on such issues were usually fueled by inter-monastic competition and provided rallying points for different networks or groupings of monks as well as the justification for dissent in the eyes of lay patrons.