Agricultural Finance Scoping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strengthening Community Systems. for HIV Treatment Scale-Up

Strengthening Community Systems. for HIV Treatment Scale-up. A case study on MaxART community. interventions in Swaziland. Colophon Strengthening Community Systems for HIV Treatment Scale-up A case study on MaxART community interventions in Swaziland Published: June 2015 Author: Françoise Jenniskens Photos: Adriaan Backer Design: de Handlangers For more information on the MaxART programme visit: www.stopaidsnow.org/treatment-prevention MINISTRY OF HEALTH KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND The Swaziland Ministry of Health, STOP AIDS NOW!, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) initiated the MaxART project in Swaziland. The programme partners include the Swaziland Network of People Living with HIV and AIDS (SWANNEPHA) and the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), the National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS (NERCHA), national and international non-governmental organisations including the Southern Africa HIV & AIDS Information Dissemination Service (SAfAIDS), social scientists from the University of Amsterdam and researchers from the South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (SACEMA). 2 Strengthening Community Systems for HIV Treatment Scale-up Acknowledgements Without the support of all the different partners in Swaziland it would not have been possible to draft this case study report. I would like to thank the respondents from the MoH and NERCHA for their extremely helpful insights in community systems strengthening issues in Swaziland and availing their time to talk to me within their busy time schedules. Furthermore I would like to express my gratitude to both Margareth Thwala-Tembe of SAfAIDS and Charlotte Lejeune of CHAI for their continuous support during my visit and for arranging all the appointments; dealing with logistics and providing transport for visiting the regions and key informants. -

Kingdom of Eswatini: 2019 Article IV Consultation-Press

IMF Country Report No. 20/41 KINGDOM OF ESWATINI 2019 ARTICLE IV CONSULTATION—PRESS RELEASE; February 2020 STAFF REPORT; AND STATEMENT BY THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FOR THE KINGDOM OF ESWATINI Under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, the IMF holds bilateral discussions with members, usually every year. In the context of the 2019 Article IV consultation with the Kingdom of Eswatini, the following documents have been released and are included in this package: • A Press Release summarizing the views of the Executive Board as expressed during its January 31, 2020 consideration of the staff report that concluded the Article IV consultation with the Kingdom of Eswatini. • The Staff Report prepared by a staff team of the IMF for the Executive Board’s consideration on January 31, 2020, following discussions that ended on November 4, 2019, with the officials of Kingdom of Eswatini on economic developments and policies. Based on information available at the time of these discussions, the staff report was completed on January 15, 2020. • An Informational Annex prepared by the IMF staff. • A Statement by the Executive Director for the Kingdom of Eswatini. The IMF’s transparency policy allows for the deletion of market-sensitive information and premature disclosure of the authorities’ policy intentions in published staff reports and other documents. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund • Publication Services PO Box 92780 • Washington, D.C. 20090 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Fax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 per printed copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. -

The Economic Benefits of Vocational Education and Training in the Kingdom of Eswatini

The Economic Benefits of Vocational Education and Training in the Kingdom of Eswatini GUGULETHU MGABHI1* AND MANGALISO MOHAMMED1 1Eswatini Economic Policy Analysis and Research Centre, Mbabane, Eswatini *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract. This study assesses the economic benefits of the Government of Eswatini’s investment to technical vocational education and training (TVET) from 2005 to 2017. TVET Graduates from 12 public TVET Institutions have been tracked to uncover their absorbability in the labour market and, or self-employment. The study finds that the economic return of the Government of Eswatini’s investment to TVET in 2017 is E1,51. This means that for every E1 invested by the Government of Eswatini to TVET, the economy generates E1,51 through the TVET graduates’ activities in self-employment, formal employment, and part-time skills utilisation. With regards to highly demanded courses amongst the graduates, ccomputer studies have been found to be highly demanded at 20.9%, while agriculture is lowly demanded at 6.3%. The study finds that 56.6% of the graduates are absorbed in formal employment, while 13.7% are engaged in self-employment, meaning that 29.9% are part of the 32.4% unemployed persons in the country. However, the level of unemployment is still high, 43.3%. Graduates who were not economically active before enrolling at the TVET colleges have been found to be formally employed, 35%, 14% are self-employed, 2.5% are both formally and self-employed, while 48.5% are unemployed. A majority (58.5%) of employed graduates are from Gwamile VOCTIM, while self-employment is high amongst graduates from Big Bend Rural Education Centre, 44.4%. -

AMERC Quarterly Review

AMERC Quarterly Review A PUBLICATION OF AFRICA MIDDLE EAST REGIONAL COMMITTEE OF IOSCO 53rd Edition / January- March 2019 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 43RD AFRICA MIDDLE EAST REGIONAL COMMITTEE MEETING 13 MAY 2019 SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA FOR AMERC PRIORITIZATION AND FOLLOW UP Dear AMERC Colleagues, Markets Authority, Saudi Arabia; Conseil du Marché I was delighted to chair the 43rd Africa Middle East Regional Financier, Tunisia; and Securities and Commodities Committee (AMERC) in Sydney, Australia on Monday, 13th Authority, United Arab Emirates. May 2019. e meeting took place within the 44th Annual e AMERC members were fortunate to engage with Chair of Meeting of the International Organization of Securities the Committee on Emerging Risks (CER) Mr. Paul Redman Commissions (IOSCO). On behalf of members, I wish to during the meeting. Mr. Redman articulately detailed the convey AMERC's appreciation to Chairman of the Australian process that is involved in development of the Risk Outlook, Securities and Investment Commission Mr. James Shipton, which is submitted to IOSCO Board for adoption annually in and IOSCO Secretary General Mr. Paul Andrews for putting October. Mr. Redman observed that seven Issue Notes were together a successful annual meeting. received from the IOSCO membership as a whole. Allow me to congratulate and also convey the commendation of IOSCO Discussion on Emerging Risks in AMERC Region Secretary General to the AMERC membership for providing e 43rd AMERC Meeting provided an opportunity for majority of the dra Issue Notes presently under members to reect on emerging risks, vulnerabilities and consideration by the CER. e submissions by AMERC trends in our region, which call for regulators' attention. -

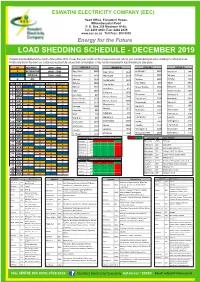

Load Shedding Schedule - December 2019

ESWATINI ELECTRICITY COMPANY (EEC) Head Office, Eluvatsini House, Mhlambanyatsi Road P. O. Box 258 Mbabane H100, Tel: 2409 4000, Fax: 2404 2335 www.eec.co.sz Toll Free: 800 9000 Energy for the Future LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE - DECEMBER 2019 Possible load shedding for the month of December 2019. Please find your location in the groups below and refer to your load shedding schedule detailing the affected areas. Kindly note that in the event our customers successfully reduce their consumption, it may not be necessary for load shedding to take place. M MORNING 10h00 - 14h00 GROUP A GROUP B GROUP C GROUP D A AFTERNOON 14h00 - 17h00 Pigg's Peak 3480 Pigg's Peak 3440 Endzingeni 3810 Mayiwane 3940 E EVENING 17h00 - 21h00 Mayiwane 3950 Mayiwane 3970 Sihhoye 2660 Sihhoye 2670 Nkhaba 3890 O OFF Sihhoye 2690 Dvokolwako 1320 Nkhaba 3860 Nkhaba 3880 Pine Valley 830 Mpisi 5640 DATE DAY GROUP A GROUP B GROUP C GROUP D Pine Valley 810 1 SUN E O M A Nkhaba 3870 Moses Hlophe 5350 Balegane 2610 Kent Rock 824 2 MON A E O M Mpisi 5650 Siteki 1230 Moses Hlophe 5360 3 TUE M A E O Balegane 2620 Kent Rock 827 Thompson 622 Siphocosini 925 4 WED O M A E Moses Hlophe 5340 5 THU E O M A Moses Hlophe 5330 Siphofaneni 5740 Riverbank 5090 Moses Hlophe 5380 6 FRI A E O M Moses Hlophe 5370 Thabankulu 3977 Manzini 1 508 7 SAT M A E O Magwabayi 542 KaLanga 1240 Big Bend 5014 Usutu 1093 8 SUN O M A E Mpaka 1227 9 MON E O M A Lobamba 950 Matsapha 2300 Sidvokodvo 630 10 TUE A E O M SPM 108 Edwaleni 104 Usutu 1094 Hlathikhulu 2180 11 WED M A E O Manzini 1 504 Sidvokodvo 636 Lawuba -

Swaziland Technology Needs Assessment Report 1

SWAZILAND TECHNOLOGY NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT 1 CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION Revised Draft 15 June 2016 Prepared by Deepa Pullanikkatil (PhD), CANGO Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background of TNA project ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 Existing national policies related to technological innovation, adaptation to climate change and development priorities ............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Vulnerability assessments in the country .................................................................................................. 11 1.4 Sector selection ......................................................................................................................................... 14 1.4.1 An Overview of Expected Climate Change and its Impacts in Sectors Vulnerable to Climate Change ... 14 1.4.2 Process and results of sector selection .................................................................................................. 24 Chapter 2 Institutional arrangement for the TNA and the stakeholder involvement ................................. 26 2.1 National TNA team .................................................................................................................................. -

Economic Impact Analysis of Credit Guarantee Schemes

Economic Impact Analysis of Credit Guarantee Schemes in Eswatini: Exploring the relationship between A Case of the Small Scale Enterprise Loan unemployment and mental illness among the Guarantee Scheme (SSELGS) youth in selected communities of Eswatini. By Maqhawe Zwane 2019 Economic Impact Analysis of Credit Guarantee Schemes in Eswatini: A Case of the Small Scale Enterprise Loan Guarantee Scheme (SSELGS) By Maqhawe Zwane Abstract Using data from 315 beneficiaries of the Small Scale Enterprise Loan Guarantee Scheme, this study assesses the impact of the Small Scale Loan Guarantee Scheme. The study assessed both the financial and economic additionality of the scheme. The study used a structured questionnaire and face-to-face interviews to elicit data from beneficiaries whereas key informant interviews were used to elicit data from participating banks. The study also assessed visibility of the scheme as well as its efficiency in terms of loan approval period and claim processes. From the sampled beneficiaries, 174 SMEs would not have accessed credit if the scheme was non-existent. Collectively, these SMEs received E42, 918,616.00. On the other hand, 72 of the 174 started new businesses and at the time of the interview, they collectively employ 681 people. The study found that the default rate is high at 44.3 %. The approval period of loan application varies widely, with some respondents reporting a period of less than a month while others reported a period of up to four years. The study concludes that the scheme has made a positive impact in both financial and economic additionality. However, two factors (inefficiency in scheme’s operation and high default rate) threaten the scheme’s existence. -

Reduction of Drought Vulnerabilities in Southern Swaziland Final Report | September 2012

Reduction of Drought Vulnerabilities in Southern Swaziland Final Report | September 2012 Cooperative agreement number DFD-G -00-09-00136-00 Start date APRIL 9, 2009 Program duration 3 YEARS Country SWAZILAND Donor budget US$ 4,998,945 Time period covered by this report APRIL 2009 – JUNE 2012 Number of individuals affected in target area 88,605 (SVAC, 2010) Number of individual beneficiaries targeted 61,370 Number of individual IDP beneficiaries targeted 0 ACRONYMS CA Conservation Agriculture DHS Demographic Health Survey EOP End of Project (endline survey) HH Household IRD International Relief and Development MT Metric Tonne OFDA Office for Foreign Disaster Assistance PTA Parent Teacher Association UN United Nations USAID US Agency for International Development VAC Vulnerability Assessment Committee WFP World Food Programme USAID/OFDA Reduction of Drought Vulnerabilities in Southern Swaziland | FINAL REPORT | 26 September 2012 | 1 Executive Summary IRD implemented a three year program (2009-2012) whose goal was “to reduce vulnerability to drought of households and communities in the Lowveld Agro-ecological zone of Swaziland” targeting 61,370 beneficiaries in the Shiselweni and Lubombo areas of the Lowveld region. This region was targeted because it covers 31% of the country and has a semiarid climate with an average annual precipitation between 400mm and 800mm, which makes it very difficult to grow crops without a moisture conservation plan. This report covers the activities conducted under the umbrella of two primary sectors, which were the focus of the 2009- 2012 IRD Swaziland’s program areas: 1. Agriculture and Food Security Objective: to improve agricultural practices under drought conditions; 2. -

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary VOL. XLVI] MBABANE, Friday, MAY 16th 2008 [No. 67 CONTENTS No. Page PART C - LEGAL NOTICE 104. Registration Centres For the 2008 General Elections................................................... SI PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 442 GENERAL NOTICE NO. 25 OF 2008 VOTERS REGISTRATION ORDER, 1992 (King’s Order in Council No.3 of 1992) REGISTRATION CENTRES FOR THE 2008 GENERAL ELECTIONS (Under Section 5(4)) Short title and commencement (1) This notice shall be cited as the Registration Centres Notice, 2008. (2) This general notice shall come into force on the date of publication in the Gazette. Registration centres for the 2008general elections It is notified for general information that the registration of all eligible voters for the 2008 general elections shall be held at Imiphakatsi (chiefdoms) and at the registration centres that have been listed in this notice; REGISTRATION CENTRES HHOHHO REGION CODE CODE CODE CHIEFDOM / POLLING Sub polling REGION INKHUNDLA STATION station 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 01 Dlangeni 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 02 Lamgabhi 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 01 Elangeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 02 Ezabeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 03 Ezulwini 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 04 Lobamba 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 05 Nkhanini 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 01 Buhlebuyeza 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 02 KaGuquka 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 03 Kuphakameni/ Dvokolwako 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 04 Mzaceni 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 05 Nyonyane / KaMaguga 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 06 Zandondo 01 HHOHHO 04 MAPHALALENI 01 Edlozini 443 -

Kingdom of Swaziland

KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTS OF THE KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31st MARCH 2017 KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND Office of the Auditor General P.O. Box 98 MBABANE H100 Swaziland Honourable M. G. Dlamini Minister for Finance P.O. Box 443 Mbabane H100 Swaziland Your Honourable, In accordance with Section 207 (5) of the Constitution of Swaziland, I have pleasure and honour to submit my report on the Audit of the Accounts of the Government of Swaziland for the financial year ended 31st March, 2017. Yours faithfully M.E Dlamini Acting Auditor General Kingdom of Swaziland Cc: The Speaker House of Assembly in Parliament Table of Contents C E R T I F I CAT E ................................................................................................................. iii Audit Opinion on the Consolidated Financial Statements .................................................... iii Basis of Opinion .................................................................................................................... iii Unadjusted Financial Statements ............................................................................................ 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 36 PART A: GENERAL MATTERS ............................................................................................ 38 1. Submission of Treasury Annual Accounts ................................................................... -

World Bank Document

48358 Public Disclosure Authorized The Government of National Emergency Council on the Kingdom of Swaziland HIV and AIDS (NERCHA) SWAZILAND HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ! For further information contact: NERCHA, SWAZILAND (National Emergency Response Council on HIV and AIDS) March 2009 P.O. Box 1937 Mbabane, Swaziland Public Disclosure Authorized February 2009 Tel: (+268) 404 1720 / 1703 Fax: (+268) 404 1692 Email: [email protected] www.nercha.org.sz The Global HIV/AIDS Program (GHAP) The World Bank SWAZILAND HIV PREVENTION RESPONSE AND MODES OF TRANSMISSION ANALYSIS Final Report March 2009 Swaziland Study Team Sibusiso Mngadi, Study Coordinator and NERCHA Focal Point Nicole Fraser, Technical Study Leader (GAMET/World Bank) Happiness Mkhatshwa, Prevention Specialist (consultant) Tyrone Lapidos, Epidemiologist (consultant) Thandi Khumalo, Sociologist (consultant) Sanelisiwe Tsela, NERCHA M&E Coordinator Nhlanhla Nhlabatsi, SNAP/MOHSW Helen Odido, UNAIDS M&E Advisor National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS World Bank Glo bal HIV/AIDS Program Global AIDS M&E Team (GAMET) © 2009 National Emergency Response Council on HIV and AIDS (NERCHA) P.O Box 1937 Mbabane, Swaziland All rights reserved. Swaziland HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis Study Team Sibusiso Mngadia, Nicole Fraser b, Happiness Mkhatshwac, Tyrone Lapidosd, Thandi Khumaloe, Sanelisiwe Tselaf, Nhlanhla Nhlabatsig, Helen Odidoh a Study Coordinator and NERCHA Focal -

Ministry of Finance

MINISTRY OF FINANCE ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2012/2013 FINANCIAL YEAR 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION ................................................................................................................................3 MISSION STATEMENT ....................................................................................................3 VALUE STATEMENT .......................................................................................................3 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ..............................................................................................3 FOREWORD……………………………………………………………………………...4 BUDGET & MONETARY AFFAIRS……….………………………...............................5 FISCAL & MONETARY AFFAIRS SECTION .................................................................7 CORPORATE SERVICES AND SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT …. ……………..13 PUBLIC ENTERPRISES UNIT ........................................................................................16 TREASURY AND STORES .............................................................................................23 INTERNAL AUDIT……………………………………………………………………..24 RECURRENT EXPENDITURE .......................................................................................27 Head 34 – Headquarters .....................................................................................................27 Head 35 – Treasury Department ........................................................................................28 Head 38 – Internal Audit....................................................................................................29