Reduction of Drought Vulnerabilities in Southern Swaziland Final Report | September 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budget Speech 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS BUDGET SPEECH 2011 I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................2 II. INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENTS ........................................5 III. DOMESTIC DEVELOPMENTS .....................................................................................6 Monetary Developments, Inflation and Interest rates ...............................................….7 Developments in External Reserves and Balance of Payments .....................................8 Financial Sector Developments .....................................................................................8 Employment opportunities .............................................................................................9 Economic Recovery Strategy.......................................................................................10 IV. THE FISCAL ADJUSTMENT ROADMAP .................................................................10 Public Enterprises ........................................................................................................12 Privatization .................................................................................................................13 V. BUDGET PERFORMANCE ..........................................................................................14 Actual outturn for 2009/2010 ......................................................................................14 Budget performance for 2010/2011 .............................................................................14 -

Strengthening Community Systems. for HIV Treatment Scale-Up

Strengthening Community Systems. for HIV Treatment Scale-up. A case study on MaxART community. interventions in Swaziland. Colophon Strengthening Community Systems for HIV Treatment Scale-up A case study on MaxART community interventions in Swaziland Published: June 2015 Author: Françoise Jenniskens Photos: Adriaan Backer Design: de Handlangers For more information on the MaxART programme visit: www.stopaidsnow.org/treatment-prevention MINISTRY OF HEALTH KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND The Swaziland Ministry of Health, STOP AIDS NOW!, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) initiated the MaxART project in Swaziland. The programme partners include the Swaziland Network of People Living with HIV and AIDS (SWANNEPHA) and the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), the National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS (NERCHA), national and international non-governmental organisations including the Southern Africa HIV & AIDS Information Dissemination Service (SAfAIDS), social scientists from the University of Amsterdam and researchers from the South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis (SACEMA). 2 Strengthening Community Systems for HIV Treatment Scale-up Acknowledgements Without the support of all the different partners in Swaziland it would not have been possible to draft this case study report. I would like to thank the respondents from the MoH and NERCHA for their extremely helpful insights in community systems strengthening issues in Swaziland and availing their time to talk to me within their busy time schedules. Furthermore I would like to express my gratitude to both Margareth Thwala-Tembe of SAfAIDS and Charlotte Lejeune of CHAI for their continuous support during my visit and for arranging all the appointments; dealing with logistics and providing transport for visiting the regions and key informants. -

Operation Update Report Southern Africa: Drought (Food Insecurity)

Operation Update Report Southern Africa: Drought (Food Insecurity) Emergency appeal n°: MDR63003 GLIDE n°: __ Operation update n° 3: 15 February 2021 Timeframe covered by this update: September 2020 – December 2020 Operation start date: 11 December 2019 Operation timeframe and end date: 17 months, 31 May 2021 Funding requirements: CHF 7.4 million DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 768,800 N° of people targeted: Botswana: 7,750 - Eswatini: 25,000 - Lesotho: 23,000 - Namibia: 18,000 Total: 73,750 people (14,750 households) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: American Red Cross, British Red Cross; Canadian Red Cross; Finnish Red Cross; Netherlands Red Cross; Spanish Red Cross; Swedish Red Cross Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Governments of Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia; Government of Japan. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), United States Agency for International Development (USAID); World Food Programme (WFP); Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO); GIZ; and UNICEF. <Please click here for the budget and here for the contacts> Summary: This operation update reflects the current situation and information available since the last operation update published in September 2020. The operation timeframe will be extended by one month to end on 31 May 2021 to allow for a final evaluation to be completed. Simultaneously, as needs persist and the funding gap in 2020 allowed to reach less than half of the targeted people in many places, extending the operation further beyond May is being discussed. Following discussions with the National Societies and estimates of needs and possible activities, a new operation update may be published to extend the timeframe or the Emergency Appeal may be revised should a change of activities be foreseen. -

2019/20 Annual Report

Vision: Vision: Partner Partner of choice of choice in alleviating in alleviating human human suffering suffering in Eswatini in Swaziland i Baphalali Eswatini Red Cross Society 2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT Mission: Saving lives, changing minds Mission: Saving lives, changing minds ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... II PRESIDENT’S REMARKS ........................................................................................................................... 1 SECRETARY GENERAL’S SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 5 ACHIEVEMENTS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES ............................................................................................... 5 1.1 PRIMARY HEALTH CARE: MOTHER, INFANT, CHILD HEALTH, CURATIVE, AND HIV/TB .. 5 2.0 FIRST AID ......................................................................................................................................... 9 3.0 DISASTER MANAGEMENT ................................................................................................................ 11 3.1 FIRE AND WINDSTORMS .................................................................................................................. -

Swaziland-VMMC-And-EIMC-Strategy

T ABLE OF C ONTENTS Table of Contents .........................................................................................................................................................................................i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................................ iii List of Boxes .............................................................................................................................................................................................. iii List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................................................... iv Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

2018 Annual Report

Vision: Vision: Partner Partner of choice of choice in alleviating in alleviating human human suffering suffering in Swaziland in Swaziland i Baphalali Eswatini Red Cross Society 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Baphalali demonstrates to a drought hit Lavumisa, Etjeni Chiefdom Community member on how to practice conservation agriculture (CA) using a seed driller. Photographer: BERCS Communications Department Mission: Saving lives, changing minds Mission: Saving lives, changing minds ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................... II PRESIDENT’S REMARKS ................................................................................................................................ 1 SECRETARY GENERAL’S SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 5 ACHIEVEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.0 HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES ................................................................................................... 5 1.1 PRIMARY HEALTH CARE: MOTHER, INFANT, CHILD HEALTH, CURATIVE, AND HIV/TB . 5 2.0 FIRST AID .............................................................................................................................................. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE the Preliminary Statement of the SADC

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Preliminary Statement of the SADC Lawyers’ Association (SADC LA) Election Observation Mission to the Kingdom of Swaziland Delivered by the Head of Mission, Professor Michelo Hansungule, on Sunday, 22nd September, 2013 at 10.00 a.m. in the Emantini Room at the Lugogo Sun, Ezulwini, Swaziland 1. Introduction The SADC Lawyers Association (SADCLA) was officially accredited to observe both the Primary and Secondary Elections in the Kingdom of Swaziland by the Election and Boundaries Commission (EBC) by way of a letter with reference number EBC/47, which was issued on 14th August, 2013. The SADCLA wishes to express gratitude to the EBC for inviting and welcoming its Election Observation Mission to observe the primary elections of the Kingdom of Swaziland, which took place on Saturday, 24 August 2013, and the secondary elections of the Kingdom of Swaziland, which took place on Friday 20 September 2013. The Association is also indebted to emaSwati, the people of the Kingdom of Swaziland, for extending a warm welcome and for their hospitality during both Observation Missions to the Kingdom of Swaziland. SADC Lawyers’ Association The SADC Lawyers’ Association (SADS LA) is an independent voluntary association made up of Law Societies and Bar Associations from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. Its mandate is to advance and promote human rights, respect for the rule of law, promote democracy and good governance in the region. In pursuit of this vision, SADC LA works very Page | 1 closely with other regional and international organisations in the legal profession to help influence politicians and decision-makers in Southern Africa to bring about just societies based on the principles of equal opportunities, independence of the judiciary and protection of fundamental liberties. -

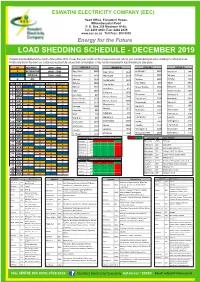

Load Shedding Schedule - December 2019

ESWATINI ELECTRICITY COMPANY (EEC) Head Office, Eluvatsini House, Mhlambanyatsi Road P. O. Box 258 Mbabane H100, Tel: 2409 4000, Fax: 2404 2335 www.eec.co.sz Toll Free: 800 9000 Energy for the Future LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE - DECEMBER 2019 Possible load shedding for the month of December 2019. Please find your location in the groups below and refer to your load shedding schedule detailing the affected areas. Kindly note that in the event our customers successfully reduce their consumption, it may not be necessary for load shedding to take place. M MORNING 10h00 - 14h00 GROUP A GROUP B GROUP C GROUP D A AFTERNOON 14h00 - 17h00 Pigg's Peak 3480 Pigg's Peak 3440 Endzingeni 3810 Mayiwane 3940 E EVENING 17h00 - 21h00 Mayiwane 3950 Mayiwane 3970 Sihhoye 2660 Sihhoye 2670 Nkhaba 3890 O OFF Sihhoye 2690 Dvokolwako 1320 Nkhaba 3860 Nkhaba 3880 Pine Valley 830 Mpisi 5640 DATE DAY GROUP A GROUP B GROUP C GROUP D Pine Valley 810 1 SUN E O M A Nkhaba 3870 Moses Hlophe 5350 Balegane 2610 Kent Rock 824 2 MON A E O M Mpisi 5650 Siteki 1230 Moses Hlophe 5360 3 TUE M A E O Balegane 2620 Kent Rock 827 Thompson 622 Siphocosini 925 4 WED O M A E Moses Hlophe 5340 5 THU E O M A Moses Hlophe 5330 Siphofaneni 5740 Riverbank 5090 Moses Hlophe 5380 6 FRI A E O M Moses Hlophe 5370 Thabankulu 3977 Manzini 1 508 7 SAT M A E O Magwabayi 542 KaLanga 1240 Big Bend 5014 Usutu 1093 8 SUN O M A E Mpaka 1227 9 MON E O M A Lobamba 950 Matsapha 2300 Sidvokodvo 630 10 TUE A E O M SPM 108 Edwaleni 104 Usutu 1094 Hlathikhulu 2180 11 WED M A E O Manzini 1 504 Sidvokodvo 636 Lawuba -

Swaziland Country Operational Plan 2018 Strategic Direction Summary

SWAZILAND Country Operational Plan (COP) 2018 Strategic Direction Summary March 29, 2018 Acronym and Word List A Adolescents AE Adverse Event AG Adolescent Girls AGYW Adolescent Girls and Young Women ALHIV Adolescents Living with HIV ANC Antenatal Clinic APR Annual Program Results ARROWS ART Referral, Retention, and Ongoing Wellness Support ARV Antiretroviral ART Antiretroviral Therapy ASLM African Society for Laboratory Medicine C Children C/A Children/Adolescents CAG Community Adherence Group CANGO Coordinating Assembly of Non-Governmental Organizations CCM Country Coordinating Mechanism CEE Core Essential Element CHAI Clinton Health Access Initiative CIHTC Community-Initiated HIV Testing and Counseling CMIS Client Management Information System CMS Central Medical Stores CoAg Cooperative Agreement CQI Continuous Quality Improvement CS(O) Civil Society (Organizations) DBS Dried Blood Spot DQA Data Quality Assessment DSD Direct Service Delivery E Swazi Emalangeni (1 lilangeni equals 1 rand) ECD Early Childhood Development EID Early Infant Diagnosis eNSF extended National Multi-Sectoral Strategic Framework for HIV & AIDS EQA External Quality Assessment DMPPT Decision Makers Program Planning Toolkit EU European Union FDC Fixed dose combination FDI Foreign Direct Investment FP Family Planning FSW Female Sex Workers GBV Gender Based Violence GHSP Global Health Services Partnership GKoS Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland GF Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income HC4 HIV -

Page 1 2018 NATIONAL ELECTIONS

2018 NATIONAL ELECTIONS - POLLING STATIONS REGION INKHUNDLA POLLING DIVISION HHOHHO HHUKWINI Dlangeni HHUKWINI KaSiko HHUKWINI Lamgabhi HHUKWINI Lamgabhi HHUKWINI Sitseni LOBAMBA Elangeni LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Ezulwini LOBAMBA Lobamba LOBAMBA Nkhanini LOBAMBA Nkhanini LOBAMBA Zabeni LOBAMBA Zabeni MADLANGEMPISI Dvokolwako / Ekuphakameni MADLANGEMPISI Dvokolwako / Ekuphakameni MADLANGEMPISI Ekukhulumeni/ Mandlangempisi MADLANGEMPISI Ekukhulumeni/ Mandlangempisi MADLANGEMPISI Gucuka MADLANGEMPISI Mavula MADLANGEMPISI Nyonyane/ Maguga MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Tfuntini/Buhlebuyeza MADLANGEMPISI Zandondo MADLANGEMPISI Zandondo MAPHALALENI Dlozini MAPHALALENI Madlolo MAPHALALENI Maphalaleni MAPHALALENI Mcengeni MAPHALALENI Mfeni MAPHALALENI Nsingweni MAPHALALENI Nsingweni MAYIWANE Herefords MAYIWANE Mavula MAYIWANE Mfasini MAYIWANE Mkhuzweni MAYIWANE Mkhuzweni MAYIWANE Mkhweni MBABANE EAST Fontein MBABANE EAST Fontein MBABANE EAST Mdzimba/Lofokati MBABANE EAST Mdzimba/Lofokati MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Msunduza MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE EAST Sidwashini MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Mangwaneni MBABANE WEST Manzana MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MBABANE WEST Nkwalini MHLANGATANE Emalibeni MHLANGATANE Mangweni MHLANGATANE Mphofu MHLANGATANE Mphofu MHLANGATANE Ndvwabangeni MHLANGATANE -

Swaziland Technology Needs Assessment Report 1

SWAZILAND TECHNOLOGY NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT 1 CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION Revised Draft 15 June 2016 Prepared by Deepa Pullanikkatil (PhD), CANGO Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background of TNA project ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.2 Existing national policies related to technological innovation, adaptation to climate change and development priorities ............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Vulnerability assessments in the country .................................................................................................. 11 1.4 Sector selection ......................................................................................................................................... 14 1.4.1 An Overview of Expected Climate Change and its Impacts in Sectors Vulnerable to Climate Change ... 14 1.4.2 Process and results of sector selection .................................................................................................. 24 Chapter 2 Institutional arrangement for the TNA and the stakeholder involvement ................................. 26 2.1 National TNA team .................................................................................................................................. -

THE STATE of WASH FINANCING in EASTERN and SOUTHERN AFRICA Eswatini Country Level Assessment

eSwatini THE STATE OF WASH FINANCING IN EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA Eswatini Country Level Assessment 1 Authors: Oliver Jones, Oxford Policy Management, in collaboration with Agua Consult and Blue Chain Consulting, Oxford, UK. Reviewers: Samuel Godfrey and Bernard Keraita, UNICEF Regional Office for Eastern and Southern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya and Boniswa Dladla (UNICEF Eswatini Country Office). Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank all other contributors from the UNICEF Eswatini Country Office, Government of the Kingdom of Eswatini and development partners. Special thanks go to UNICEF Eswatini for facilitating the data collection process in-country. September 2019 Table of contents The State of WASH Financing in Eastern and Southern Africa Eswatini Country Level Assessment Table of contents List of abbreviations v 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Methodology 1 1.3 Caveats 2 1.4 Report structure 3 2 Country Context 4 2.1 History/geography 4 2.2 Demography 4 2.3 Macroeconomy 5 2.4 Private Sector Overview 6 2.5 Administrative setup 7 3 WASH Sector Context 8 3.1 Access to WASH Services 8 3.2 Institutional Structures 10 3.3 WASH sector policies, strategies and plans 11 3.4 WASH and Private Sector Involvement 12 4 Government financing of WASH services 13 4.1 Recent Trends 13 4.2 Sector Financing of Strategies and Plans 16 4.3 Framework for donor engagement in the sector 17 5 Donor financing of WASH services 19 5.1 Recent trends 19 5.2 Main Modalities 22 5.3 Coordination of donor support 23 6 Consumer financing of WASH services 24