Ecri Report on Austria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

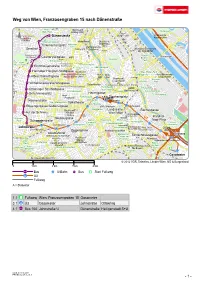

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Erika Weinzierl Emeritus Professor of History University of Vienna Working Paper 01-1 October 2003 ©2003 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: The Rise of the Viennese Jewish Middle Class The rapid burgeoning and advancement of the Jewish middle class in Vienna commenced with the achievement of fully equal civil and legal rights in the Fundamental Laws of December 1867 and the inter-confessional Settlement (Ausgleich) of 1868. It was the victory of liberalism and the constitutional state, a victory which had immediate and phenomenal demographic and social consequences. In 1857, Vienna had a total population of 287,824, of which 6,217 (2.16 per cent) were Jews. -

Menschen in Wien | 5

STATISTISCHES JAHRBUCH DER STADT WIEN - 2017 55 MENSCHEN IN WIEN | 5. Bevölkerung 5. Bevölkerung ....................................................................55 5.1 Bevölkerungsentwicklung...............................................59 MENSCHEN 5.2 Bevölkerungsstruktur .....................................................64 5.3 Natürliche Bevölkerungsbewegung .................................73 5.4 Einbürgerungen .............................................................81 IN WIEN 5.5 Gesamtwanderung .........................................................84 5.6 Außenwanderung...........................................................89 5.7 Binnenwanderung..........................................................94 5.8 Bevölkerungsprognose...................................................98 6. Gesundheit....................................................................103 6.1 Medizinische Versorgung..............................................106 6.2 Geburten und Säuglingssterblichkeit ............................110 6.3 Erkrankungen ..............................................................111 6.4 Todesursachen.............................................................115 7. Bildung .........................................................................117 7.1 Institutionelle Kinderbetreuung ....................................120 7.2 Schulen .......................................................................123 7.3 Universitäten und Fachhochschulen .............................128 7.4 Bildungsstand und Bildungsausgaben -

Analysing Spatial Patterns of Social Housing Schemes in Vienna and Copenhagen

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit Location of Social Housing: Analysing spatial patterns of social housing schemes in Vienna and Copenhagen Verfasserin DI Sandra Jurasszovich angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 1. September 2015 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 664 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium DDP Urban Studies Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Jesús Leal (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) Sandra Jurasszovich Location of Social Housing: Analysing spatial spatial patterns of social housing schemes in Vienna and Copenhagen Erasmus Mundus Master Course in Urban Studies [4Cities] 2013-2015 1st of September 2015 Supervisor: Jesús Leal Abstract Providing social housing is a crucial subject in current political debate as well as in scientific literature. When examining the topic of social housing there are two major issues: firstly, what socio- demographic groups are entitled to benefit from social housing and how has the socio-economic composition changed over the last decades? And secondly, where in a city are social housing units built? The latter question, which is related to the planning system of a city, is oftentimes underestimated, disregarded or simply overlooked in literature covering social housing in Europe. This thesis addresses exactly this problem, its objective being the identification of how the planning systems are used to influence the location of social housing developments across urban space by the example of Vienna and Copenhagen. Both cities have repeatedly been appraised as being amongst the most liveable cities worldwide. As a result of their increasing attractiveness as a place to live in, land and housing prices have been soaring. The research underlines that the possibilities for providers of social housing are limited considerably by high land price. -

First Vienna Residential Market Report | 2021 02

FIRST VIENNA RESIDENTIAL MARKET REPORT EDITION 2021 Illus fehlen hier noch EDITORIAL issues such as: What role does digitalisation play in the residential space? DEAR READER How can we best combine sustainability and affordability in residential de- velopment projects? How will future residential project planning respond We are pleased to present the First Vienna Residential Market Report, the to the increased trend of working from home in the light of the pandemic? ninth edition of our joint publication. We will be going into this last question on page 14. THIS HAS BEEN A TURBULENT YEAR with the pandemic leav- ing its mark on every aspect of the economy, resulting in long-term ef- fects for many. The real estate industry has not remained unscathed by the crisis, although the residential market is showing significantly more “The past year has brought even more focus on stability: The demand for residential accommodation remained high in the home, raising important questions concern- 2020 – probably due to the fact that residential property is a safe form of investment in general. ing the housing market.” THE HIGH DEMAND also resulted from constantly increasing numbers of one-person households and the continued rise in Vienna’s population, which is due to reach the two million mark in 2028. In contrast, property IN THE FIRST VIENNA RESIDENTIAL MARKET REPORT, we developers in 2021 will still have challenges to face as land available for will be sharing our experience and expertise for a more in-depth and com- development has become scarce in the capital and construction costs are prehensive insight into the market. -

Changes in Water and Land: the Reconstructed Viennese Riverscape from 1500 to the Present

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Water Hist (2013) 5:145–172 DOI 10.1007/s12685-013-0074-2 Changes in water and land: the reconstructed Viennese riverscape from 1500 to the present Severin Hohensinner • Bernhard Lager • Christoph Sonnlechner • Gertrud Haidvogl • Sylvia Gierlinger • Martin Schmid • Fridolin Krausmann • Verena Winiwarter Received: 12 September 2012 / Accepted: 23 March 2013 Ó The Author(s) 2013. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Medieval Vienna was situated at the main arm of the swiftly flowing alpine Danube. From the fourteenth century onwards, the river gradually moved away from the city. This marked the beginning of 500 years of human intervention to prevent further displacement of the river and to preserve the waterway as a vital supply line. Archival research and the GIS-based reconstruction of the past riverscape allow a new view about the co-evolution of the city and the river. Following major channel changes in 1565/1566, repeated attempts to force the main arm into the old river bed were undertaken. By the early seventeenth century, the Viennese had accepted the new situation. Resources were S. Hohensinner (&) Á B. Lager Á G. Haidvogl Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management (IHG), University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU), Max-Emanuel-Str. 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria e-mail: [email protected] B. Lager e-mail: [email protected] G. Haidvogl e-mail: [email protected] C. Sonnlechner Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna, Rathaus, 1082 Vienna, Austria e-mail: [email protected] S. -

Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Housing in Vienna

Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 Housing in Vienna Housing in Vienna Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Online at www.wohnbauforschung.at Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Contents STUDIOVLAY Foreword Management and Care Dedicated with Heart and Passion Page 7 At Home in a Municipal Housing Page 28 Wohnservice Wien - Bundling Service Skills Page 30 Introduction Mieterhilfe - The Experts in Rental Law Page 32 Social Housing Shapes the Future Page 10 wohnpartner: Working Together for a Good Neighborhood Page 34 Funding Social Housing Advice on Funding Page 36 Subsidized Housing Projects Page 16 Decorative Figures on the Town Hall Page 37 Page 20 Biotope City in Favoriten Research & Innovation An Additional Tool for Affordable Housing Page 21 IBA_Vienna 2022 - New Social Housing Page 40 Involving the Neighborhood Page 22 Smarter Together Page 42 Modern Living with Historic Flair Page 24 Well-Founded Know-How Page 44 Trailblazer Page 45 Notes Page 48 4 Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 Housing in Vienna Annual Report 2016 5 Foreword Sonnwendviertel, plot C.01 Architecture: Univ.-Prof. Arch. DI Klaus Kada / Riepl Riepl Architects / DI Bernd Vlay and Mag.a arch. Karoline Streeruwitz Spatial planning: rajek barosch landschaftsarchitektur Developer: win4wien Dedicated with Heart and Passion The City of Vienna is known for its special focus on social dimension in urban housing far beyond mere economic criteria. Thanks to decades of political emphasis on afforda- ble housing, Vienna is currently in a much better position than other metropolitan cities, where social housing has been either neglected or even completely abandoned. -

DELIVERABLE PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Systemic Seismic Vulnerability and Risk Analysis for Buildings, Lifeline Networks

D 6.2 DELIVERABLE PROJECT INFORMATION Systemic Seismic Vulnerability and Risk Analysis for Project Title: Buildings, Lifeline Networks and Infrastructures Safety Gain Acronym: SYNER-G Project N°: 244061 Call N°: FP7-ENV-2009-1 Project start: 01 November 2009 Duration: 36 months DELIVERABLE INFORMATION D6.2 Application and validation study to the city of Vienna Deliverable Title: (Austria) Date of issue: February 2013 Work Package: WP6 – Validation studies Deliverable/Task Leader: VCE – Vienna Consulting Engineers REVISION: FINAL Project Coordinator: Prof. Kyriazis Pitilakis Institution: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki e-mail: [email protected] fax: + 30 2310 995619 telephone: + 30 2310 995693 Abstract The test case in Vienna shows some very interesting results. The methods that have been produced in the project have been tested in a very small area of a big city. This brings some major difficulties for both the software package as well as for the data collection. In general, the theoretical background that has been produced in the various work packages of the project was brought into practise successfully. The interdependencies of systems and their interactions within the system have been shown in the OOFIMS case of the Test Study. The EQvis case shows that the software packages have to be user friendly and easy to handle. The visualisation of the results plays a major role when dealing with stakeholders and officials. EQvis has brought together all these components in one software solution which is easy to handle. Keywords: Validation, Case Study, Vienna, Application i Acknowledgments The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007-2013] under grant agreement n° 244061. -

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria Subsidizes Scientific And

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria subsidizes scientific and pedagogical projects which foster tolerance and mutual understanding on the basis of a close examination of the sufferings caused by the Nazi regime on the territory of present-day Austria. Keeping alive the memory of the victims as a reminder for future generations is one of our main targets, as well as human rights education and the strengthening of democratic values. Beyond, you will find a list containing the English titles or brief summaries of all projects approved by the Future Fund since its establishment in 2006. For further information in German about the content, duration and leading institutions or persons of each project, please refer to the database (menu: “Projektdatenbank”) on our homepage http://www.zukunftsfonds-austria.at If you have further questions, please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] Project-Code P06-0001 brief summary Soviet Forced Labour Workers and their Lives after Liberation Project-Code P06-0002 brief summary Life histories of forced labour workers under the Nazi regime Project-Code P06-0003 brief summary Unbroken Will - USA - Tour 2006 (book presentations and oral history debates with Holocaust survivor Leopold Engleitner) Project-Code P06-0004 brief summary Heinrich Steinitz - Lawyer, Poet and Resistance Activist Project-Code P06-0006 brief summary Robert Quintilla: A Gaul in Danubia. Memoirs of a former French forced labourer Project-Code P06-0007 brief summary Symposium of the Jewish Museum Vilnius on their educational campaign against anti-Semitism and Austria's contribution to those efforts Project-Code P06-0008 brief summary Effective Mechanisms of Totalitarian Developments. -

VHS DONAUSTADT Kursprogramm Frühjahr 2020

VHS DONAUSTADT Kursprogramm Frühjahr 2020 Bildung www.vhs.at/donaustadt +43 1 891 74-122 000 und Jugend Volkshochschule Donaustadt Kursorte der VHS Donaustadt im Frühjahrssemester 2020 VHS Donaustadt – 1220, Bernoullistraße 1 (U1 Kagran, Straßenbahn 25, Bus 26A) VHS Eibengasse – 1220, Eibengasse 57 (U2 Donauspital, Straßenbahn 25, Bus 26A) NMS Anton Sattler Gasse – 1220, Anton-Sattler-Gasse 93 (U1 Kagran, Straßenbahn 25) VS Asperner Heldenplatz – 1220, Asperner Heldenplatz (Straßenbahn 25) MMS Eibengasse – 1220, Eibengasse 58 (U2 Donauspital, Straßenbahn 25, Bus 26A) GTVS Hammerfestweg – 1220, Hammerfestweg 1 (U2 Donauspital, Straßenbahn 25, Bus 26A) BG Heustadelgasse – 1220, Heustadelgasse 4 (Bus 26A, Straßenbahn 25) NMS Konstanziagasse KO50 – 1220, Konstanziagasse 50 (U2 Hardegggasse, Straßenbahn 25) VS Natorpgasse – 1220, Natorpgasse 1 (Bus 94A) BG Polgarstraße – 1220, Polgarstraße 24 (Bus 26A, Straßenbahn 25, Bus 94A, S80) Campus Seestadt – 1220, Maria Trapp-Platz 5 (U2 Seestadt, Bus 84A, Bus 88A) WMS Simonsgasse – 1220, Simonsgasse 23 (Bus 26A) Jot12 – 1220, Sonnenalle 26/Eingang Frenkel-Brunswick-Gasse (U2 Seestadt, Bus 84A, Bus 88A) Polytechnikum Wintzingerodestraße – 1220, Wintzingerodestraße 1–3 (U1 Kagran) Wir bedanken uns für die freundliche Aufnahme an den Standorten und die gute Zusammenarbeit mit unseren KooperationspartnerInnen vor Ort! Bitte beachten Sie die Kursortangabe auf Ihrer Kurskarte. In Ausnahmefällen kann der Kursort noch kurzfristig vor Kurs beginn geändert werden. Für Fragen, Anregungen, Wünsche, Beschwerden